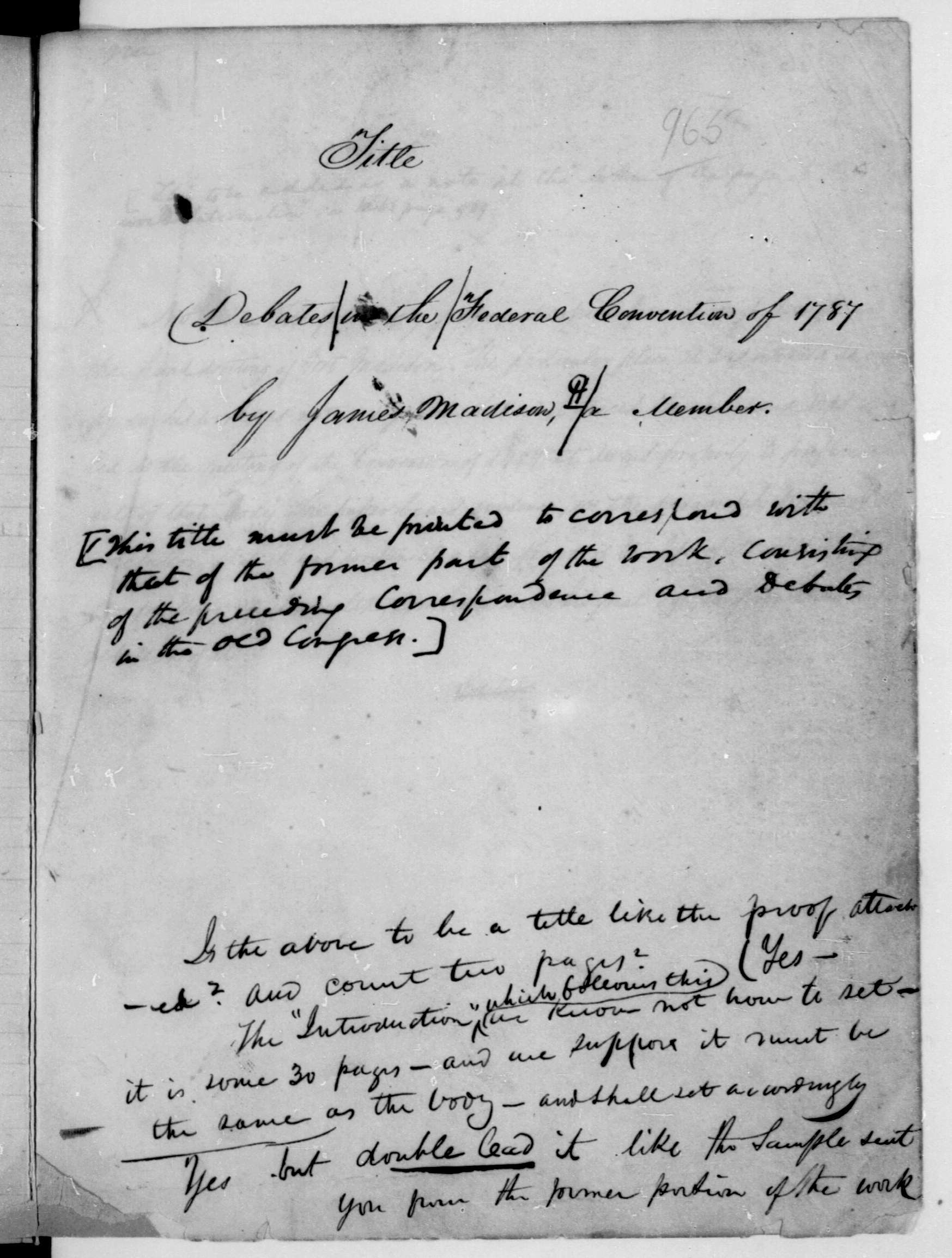

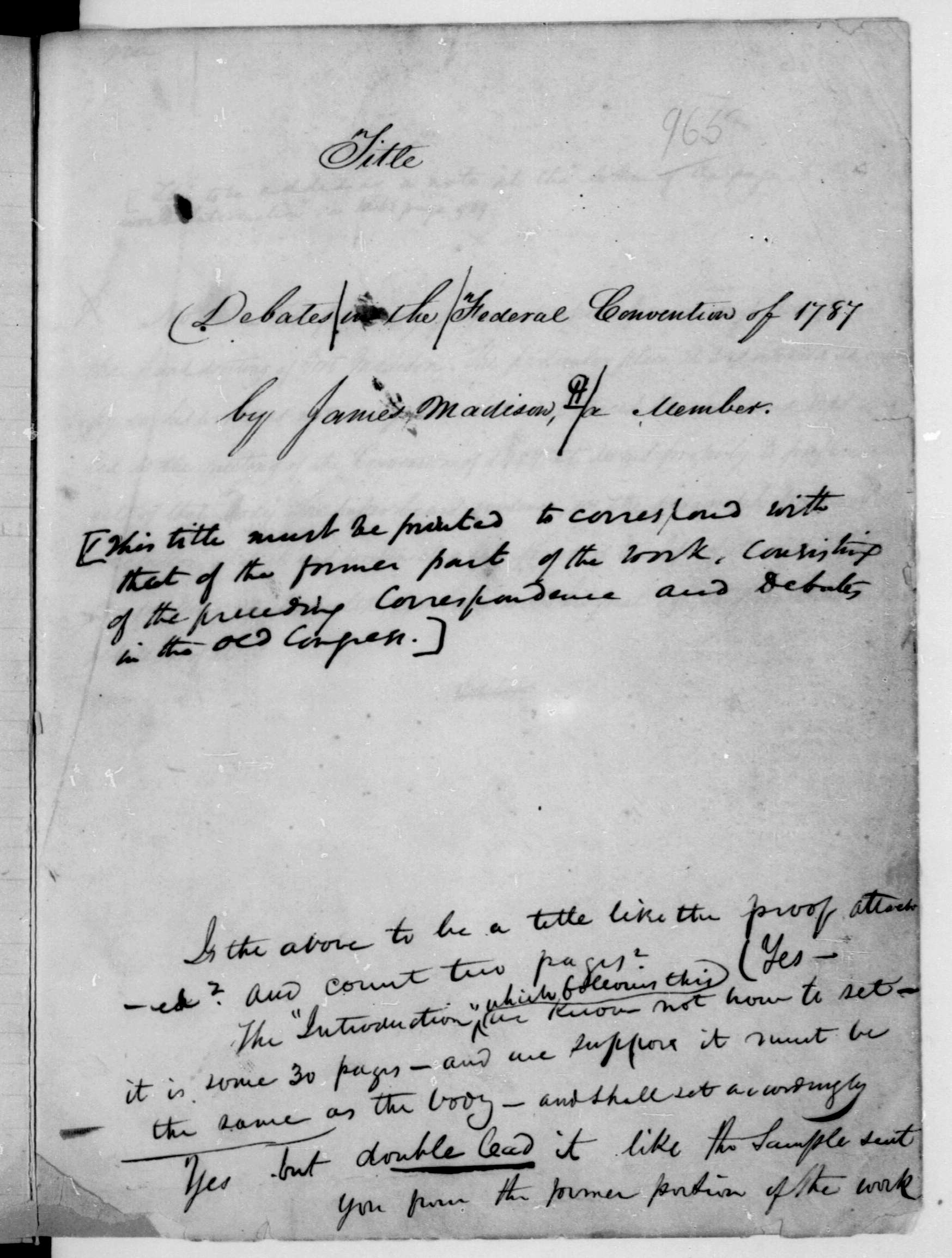

“From James Madison to James Monroe, 10 June 1787,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/ky9o.

Dear Sir

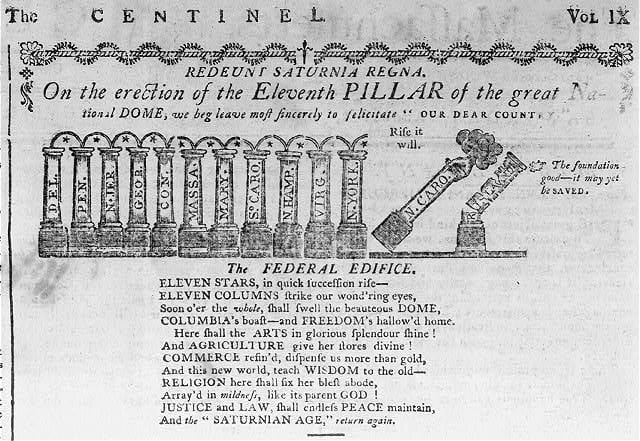

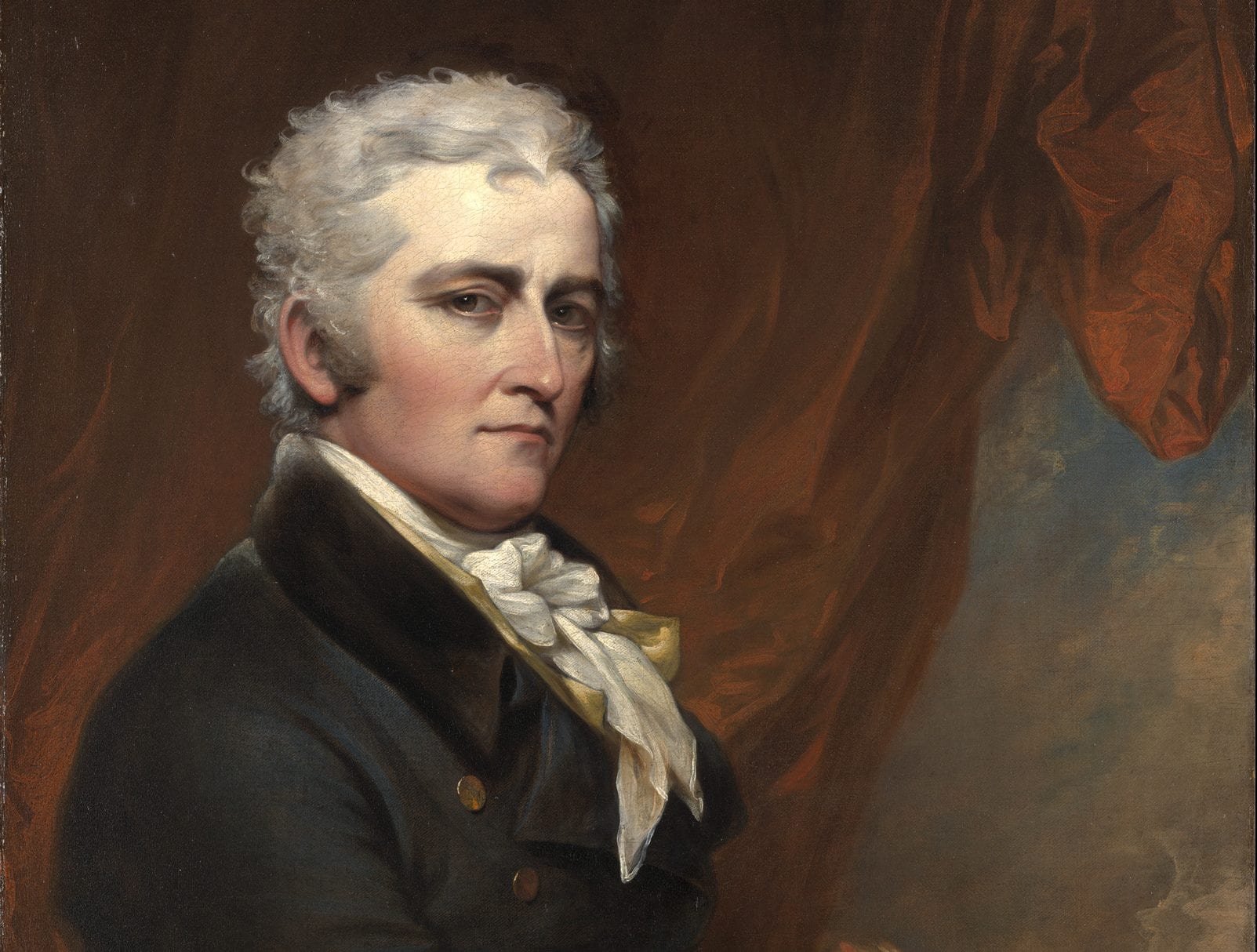

I have been discouraged from answering sooner your favor of by the bar which opposes such communications as I should incline not less to make than you must do to receive. One of the earliest rules established by the Convention restrained the members from any disclosure whatever of its proceedings, a restraint which will not probably be removed for some time. I think the rule was a prudent one not only as it will effectually secure the requisite freedom of discussion, but as it will save both the Convention and the Community from a thousand erroneous and perhaps mischievous reports. I feel notwithstanding great mortification in the disappointment it obliges me to throw on the curiosity of my friends. The Convention is now as full as we expect it to be unless a report should be true that Rh. Island has it in contemplation to make one of the party. If her deputies should bring with them the complexion of the State, their company will not add much to our pleasure, or to the progress of the business. Eleven States are on the floor. All the deputies from Virga. Remain except Mr. Wythe who was called away some days ago by information from Williamsburg concerning the increase of his lady’s ill health. I had a letter by the last packet from Mr. Short, but not any from Mr. Jefferson. The latter had sett out on his tour to the South of France. Mr. Short did not expect his return for a considerable time. The last letter from him assigned as the principal motive to this ramble, the hope that some of mineral springs in that quarter might contribute to restore his injured wrist. Present me most respectfully to Mrs. Monroe. Yrs. Affecy.

Js. Madison Jr.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)