Introduction

Monday May 14 was the day chosen by the Annapolis convention and confirmed by the Confederation Congress for the beginning of the Grand Convention. But only eight delegates were present on May 14 – four from Pennsylvania and four from Virginia. On May 25, seven of the states met their internal quorum requirement and so a majority (seven) of the thirteen states were represented at the Constitutional Convention. The deliberations could finally begin.

The rules adopted reinforced an irony: a convention called to reconsider the efficacy of the Articles of Confederation began by adopting, without argument, five voting rules of the Articles: (1) a quorum required a majority of states, (2) each state was allotted one vote, (3) the voting was to be by states and not by individuals, (4) each state set its own internal quorum requirements, and (5) each state could send up to seven delegates. (The Convention, without argument, accepted Benjamin Franklin as an eighth Pennsylvania delegate.)

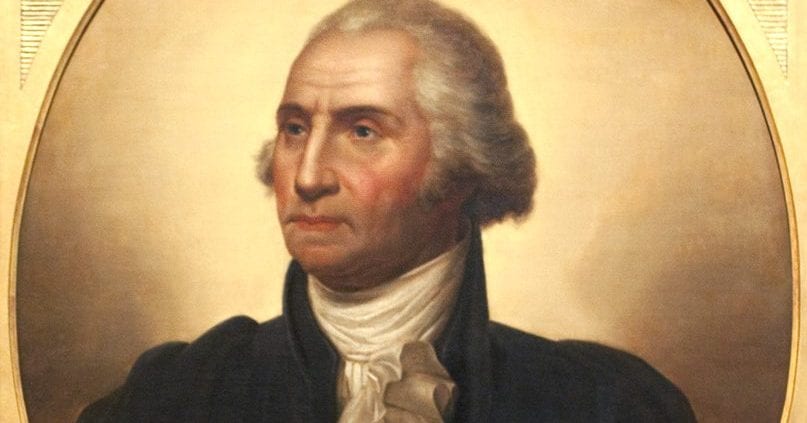

Among the most important of the rules adopted at the Convention was closing the curtains over the windows and adopting what unsympathetic historians over the decades have called the “secrecy rule.” The merits and demerits of the secrecy rule have been a subject of considerable debate throughout American history. Jefferson disapproved of the rule: “I am sorry they began their deliberations,” he wrote to John Adams, “by so abominable a precedent as that of tying up the tongues of their members. Nothing can justify this example but the innocence of their intentions, and ignorance of the value of public discussions.” Madison, however, supported the rule of secrecy. To James Monroe he wrote, “I think the rule was a prudent one not only as it will effectually secure the requisite freedom of discussion, but as it will save both the Convention and the Community from a thousand erroneous and perhaps mischievous reports.”

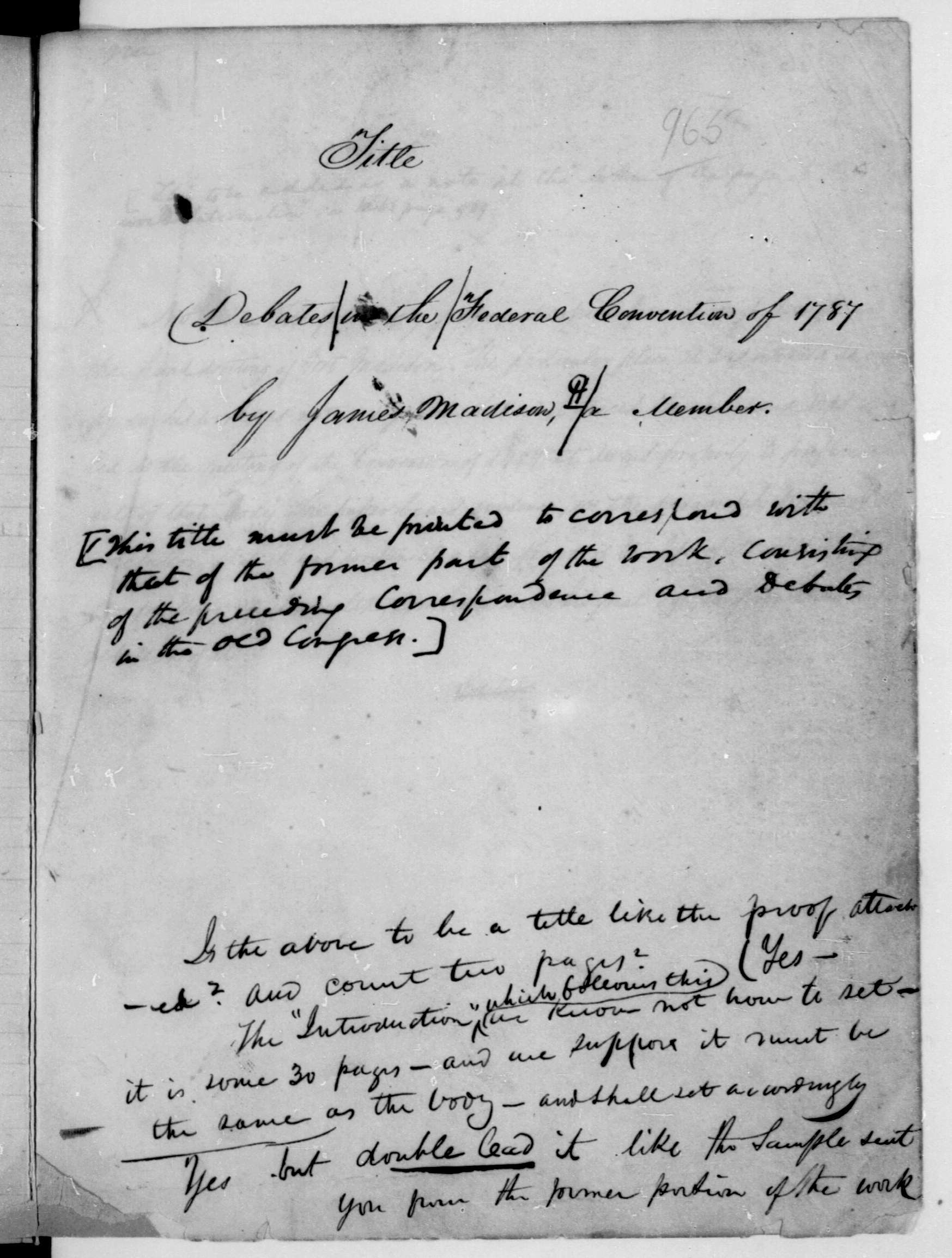

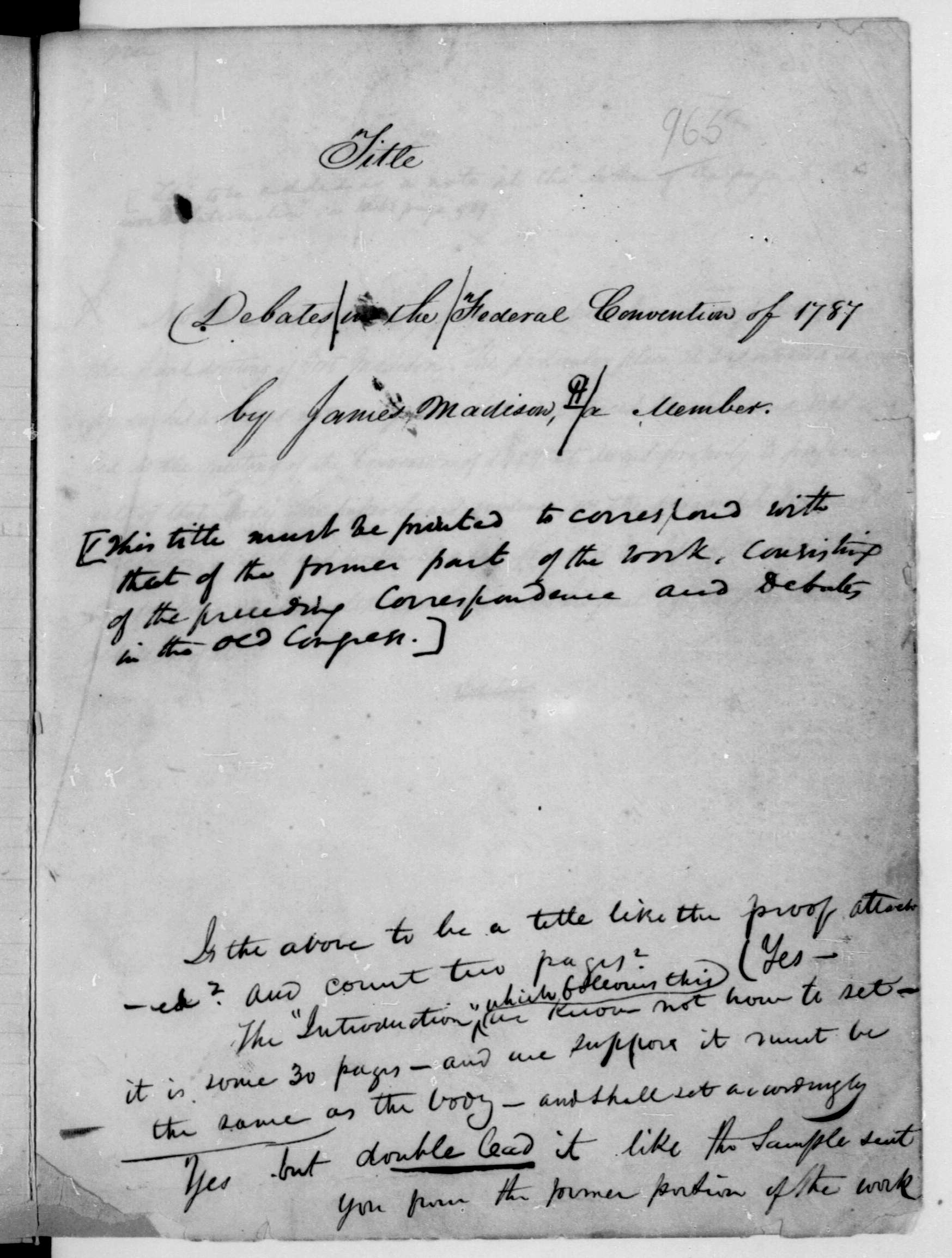

Source: Gordon Lloyd, ed., Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 by James Madison, a Member (Ashland, OH: Ashbrook Center, 2014), 3–6.

Monday, May 28

. . . Mr. Wythe[1] from the Committee for preparing rules, made a report, which employed the deliberations of this day.

Mr. King[2] objected to one of the rules in the report authorizing any member to call for the Yeas and Nays and have them entered on the minutes. He urged that, as the acts of the Convention were not to bind the constituents, it was unnecessary to exhibit this evidence of the votes; and improper, as changes of opinion would be frequent in the course of the business, and would fill the minutes with contradictions.

Colonel Mason[3] seconded the objection, adding, that such a record of the opinions of members would be an obstacle to a change of them on conviction; and in case of its being hereafter promulgated, must furnish handles to the adversaries of the result of the meeting.

The proposed rule was rejected, nem. con.[4] The standing rules agreed to were as follows:

RULES

“A House to do business shall consist of the Deputies of not less than seven States; and all questions shall be decided by the greater number of these which shall be fully represented. But a less number than seven may adjourn from day to day.

“Immediately after the President shall have taken the Chair, and the members their seats, the minutes of the preceding day shall be read by the Secretary.

“Every member, rising to speak, shall address the President; and, while he shall be speaking, none shall pass between them, or hold discourse with another, or read a book, pamphlet, or paper, printed or manuscript. And of two members rising to speak at the same time, the President shall name him who shall be first heard.

“A member shall not speak oftener than twice, without special leave, upon the same question; and not the second time, before every other who had been silent shall have been heard, if he choose to speak upon the subject.

“A motion, made and seconded, shall be repeated, and, if written, as it shall be when any member shall so require, read aloud, by the Secretary, before it shall be debated; and may be withdrawn at any time before the vote upon it shall have been declared.

“Orders of the day shall be read next after the minutes; and either discussed or postponed, before any other business shall be introduced.

“When a debate shall arise upon a question, no motion, other than to amend the question, to commit it, or to postpone the debate, shall be received.

“A question which is complicated shall, at the request of any member, be divided, and put separately upon the propositions of which it is compounded.

“The determination of a question, although fully debated, shall be postponed, if the Deputies of any State desire it, until the next day.

“A writing which contains any matter brought on to be considered shall be read once throughout, for information; then by paragraphs, to be debated; and again, with the amendments, if any, made on the second reading; and afterwards the question shall be put upon the whole, amended, or approved in its original form, as the case shall be.

“Committees shall be appointed by ballot; and the members who have the greatest number of ballots, although not a majority of the votes present, shall be the Committee. When two or more members have an equal number of votes, the member standing first on the list, in the order of taking down the ballots, shall be preferred.

“A member may be called to order by any other member, as well as by the President; and may be allowed to explain his conduct, or expressions, supposed to be reprehensible. And all questions of order shall be decided by the President, without appeal or debate.

“Upon a question to adjourn, for the day, which may be made at any time, if it be seconded, the question shall be put without a debate.

“When the House shall adjourn, every member shall stand in his place until the President pass him.”* . . .

Mr. Butler[5] moved that the House provide against interruption of business by absence of members, and against licentious publications of their proceedings.

To which was added, by Mr. Spaight,[6] a motion to provide that, on the one hand, the House might not be precluded by a vote upon any question from revising the subject matter of it, when they see cause, nor, on the other hand, be led too hastily to rescind a decision which was the result of mature discussion. Whereupon it was ordered, that these motions be referred for the consideration of the Committee appointed to draw up the standing rules, and that the Committee make report thereon.

Adjourned till tomorrow, at ten o’clock.

* [Madison footnote]

Previous to the arrival of a majority of the States, the rule by which they ought to vote in the Convention had been made a subject of conversation among the members present. It was pressed by Gouverneur Morris,[7] and favored by Robert Morris[8] and others from Pennsylvania, that the large States should unite in firmly refusing to the small States an equal vote, as unreasonable, and as enabling the small states to negative every good system of government, which must, in the nature of things, be founded on a violation of that equality. The members from Virginia, conceiving that such an attempt might beget fatal altercations between the large and small States; and that it would be easier to prevail on the latter, in the course of the deliberations, to give up their equality for the sake of an effective government, than, on taking the field of discussion, to disarm themselves of the right, and thereby throw themselves on the mercy of the larger States, discountenanced and stifled the project.

May 29

. . . The following rules were added, on the Report of Mr. Wythe from the Committee –

“That no member be absent from the House, so as to interrupt the representation of the State, without leave.

“That Committees do not sit whilst the House shall be, or ought to be, sitting.

“That no copy be taken of any entry on the Journal, during the sitting of the House, without leave of the House.

“That members only be permitted to inspect the Journal.

“That nothing spoken in the House be printed, or otherwise published, or communicated, without leave.

“That a motion to reconsider a matter which has been determined by a majority, may be made, with leave, unanimously given, on the same day on which the vote passed; but otherwise, not without one day’s previous notice; in which last case, if the House agree to the reconsideration, some future day shall be assigned for that purpose.”

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)