Introduction

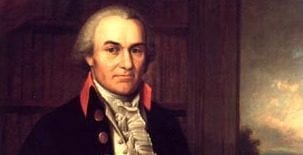

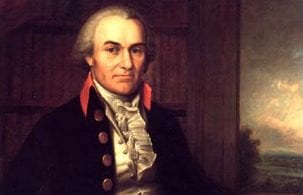

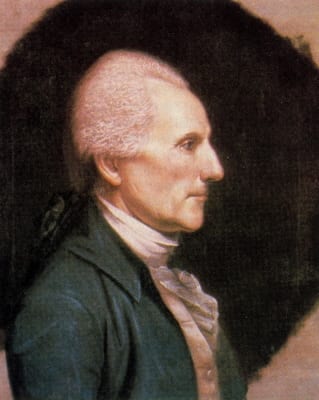

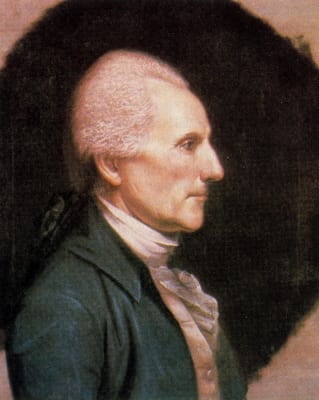

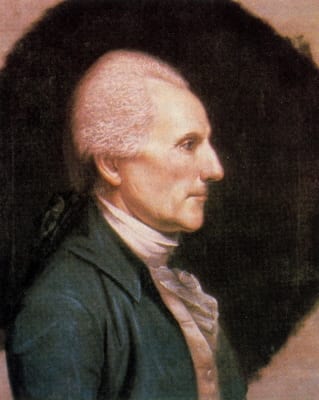

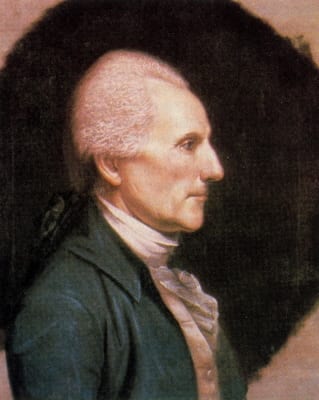

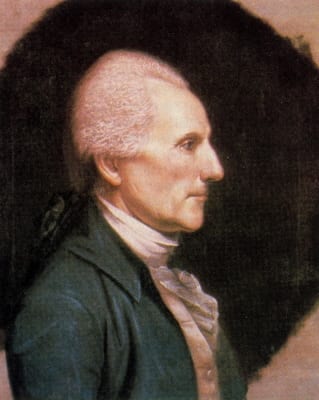

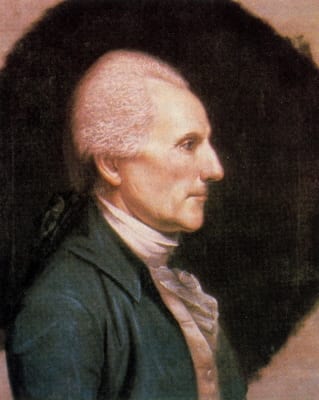

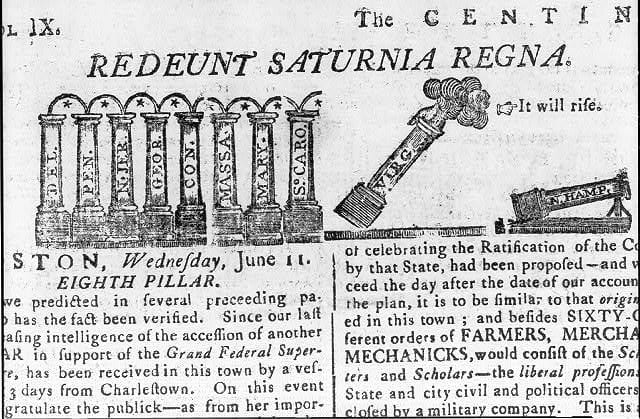

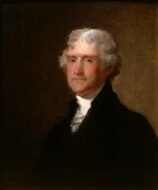

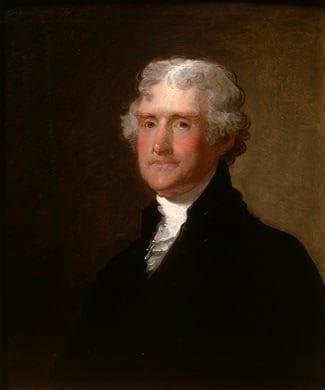

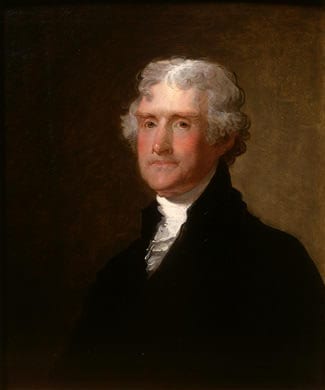

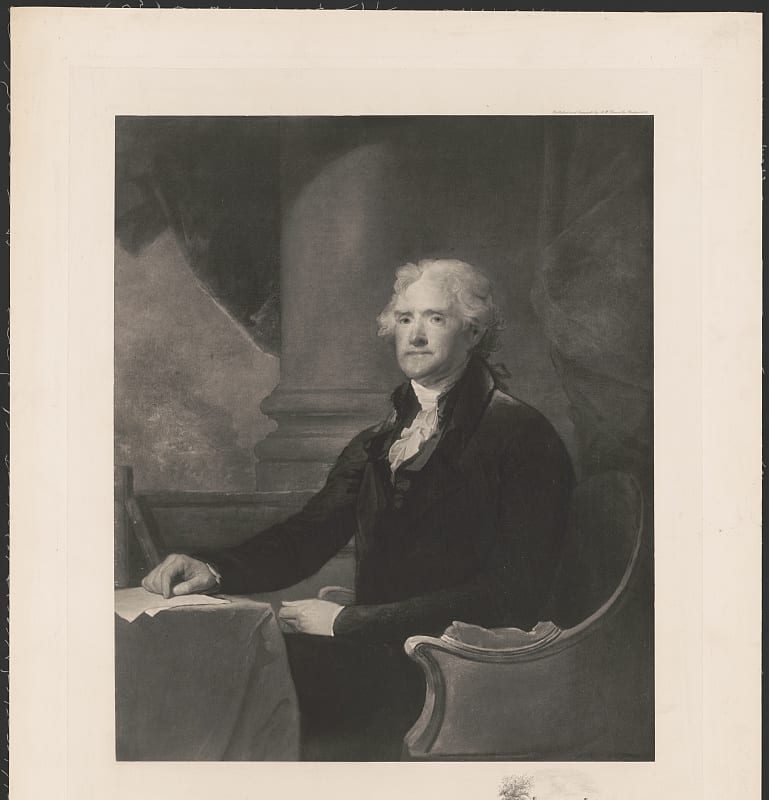

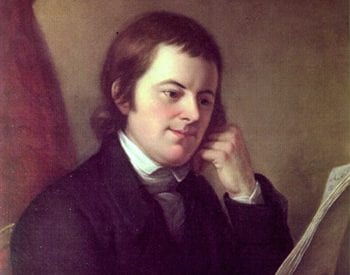

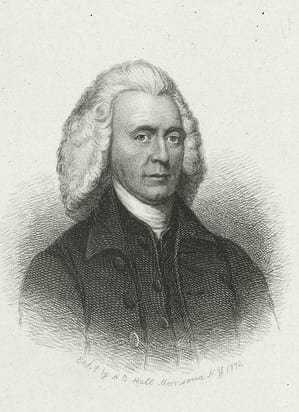

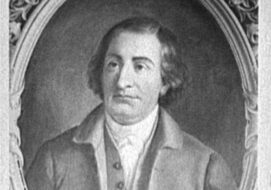

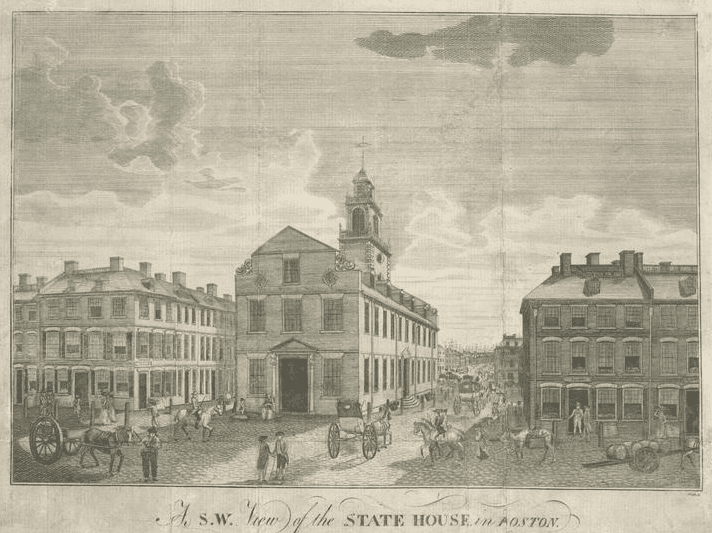

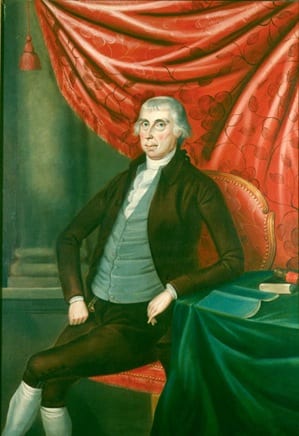

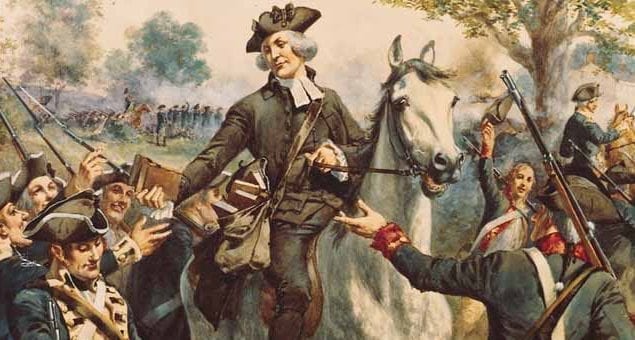

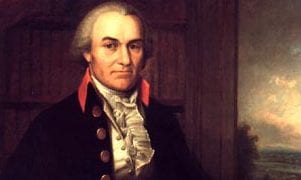

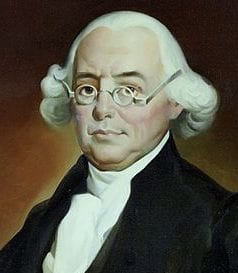

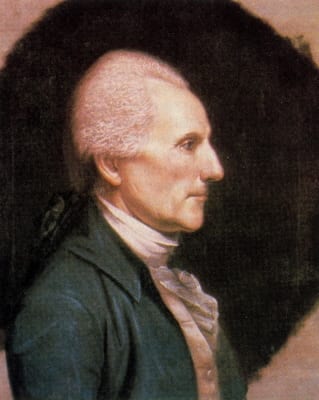

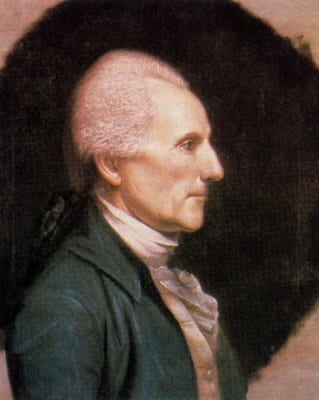

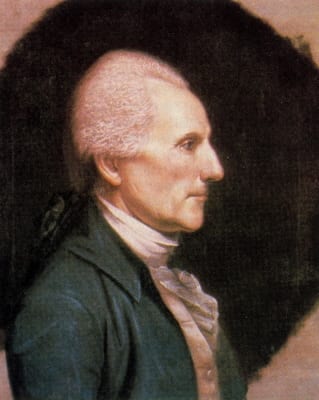

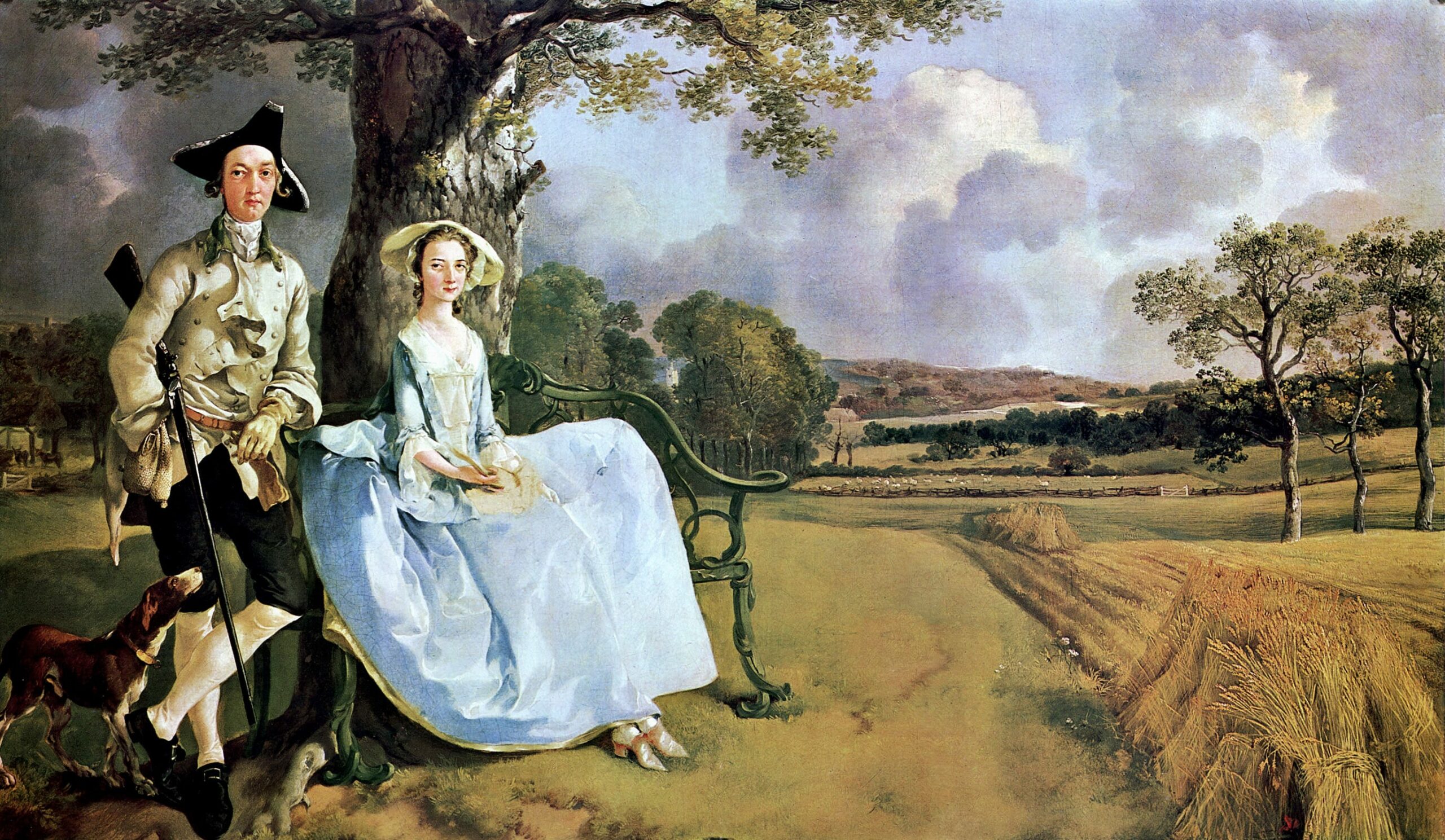

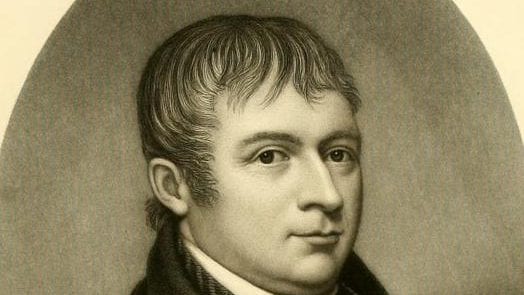

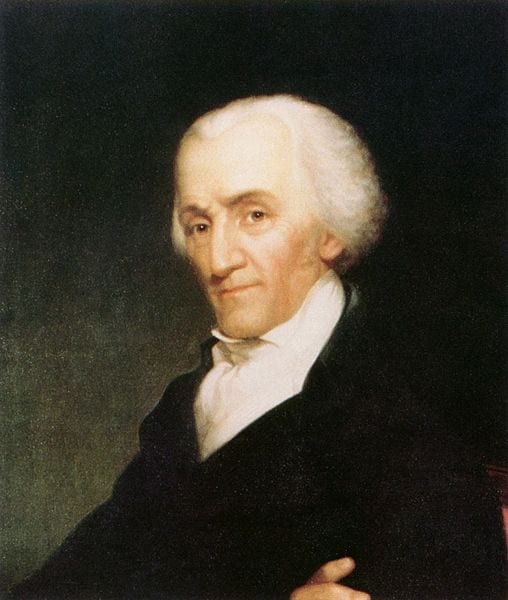

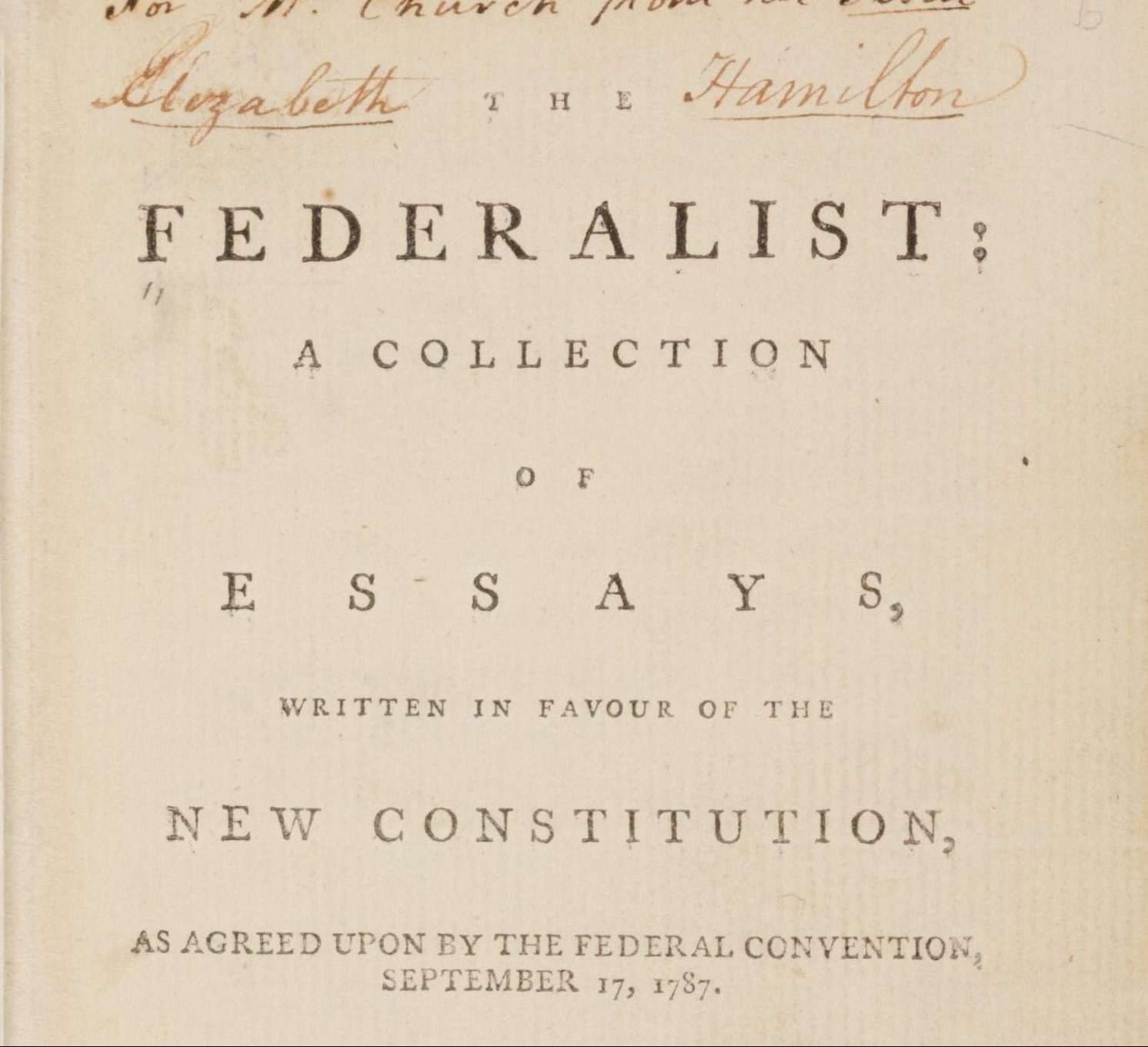

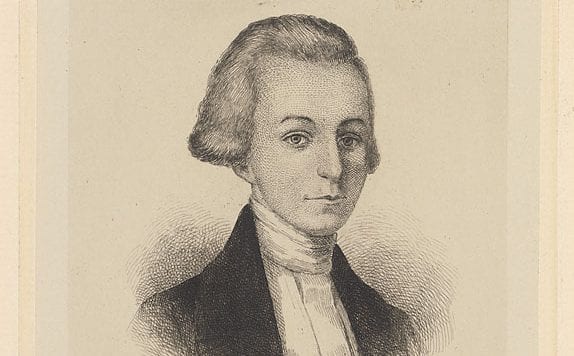

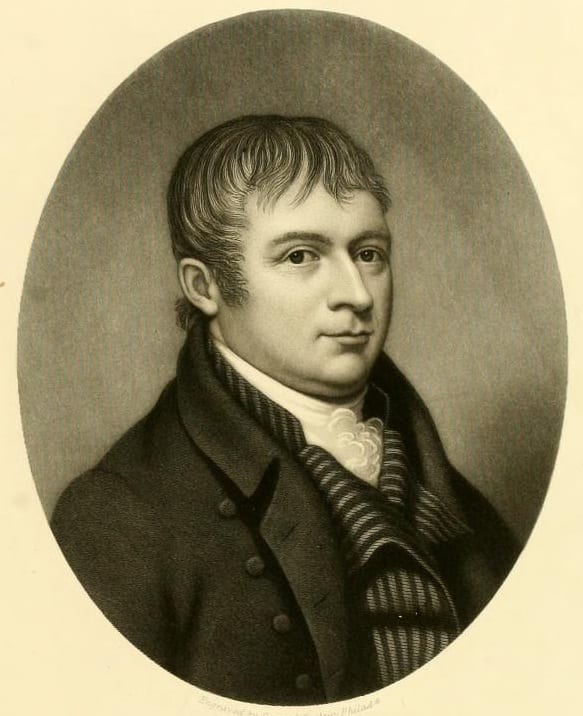

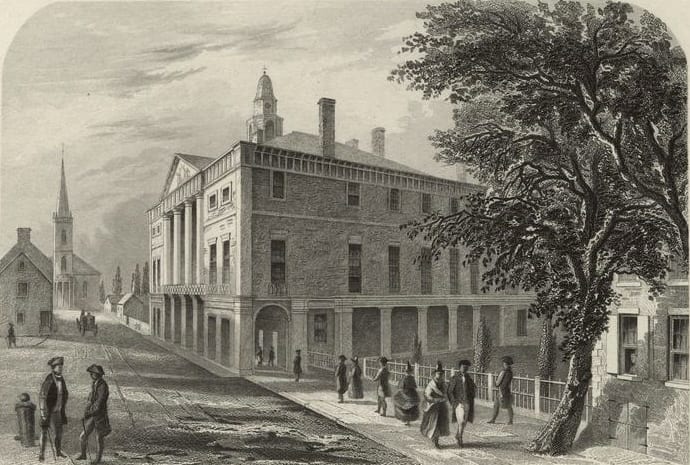

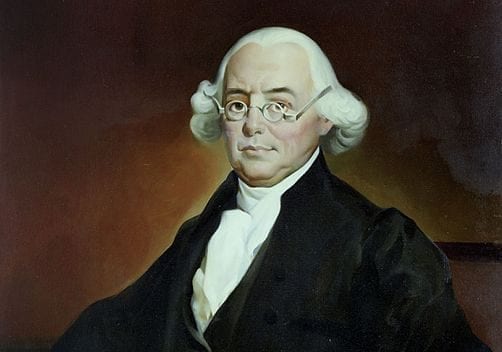

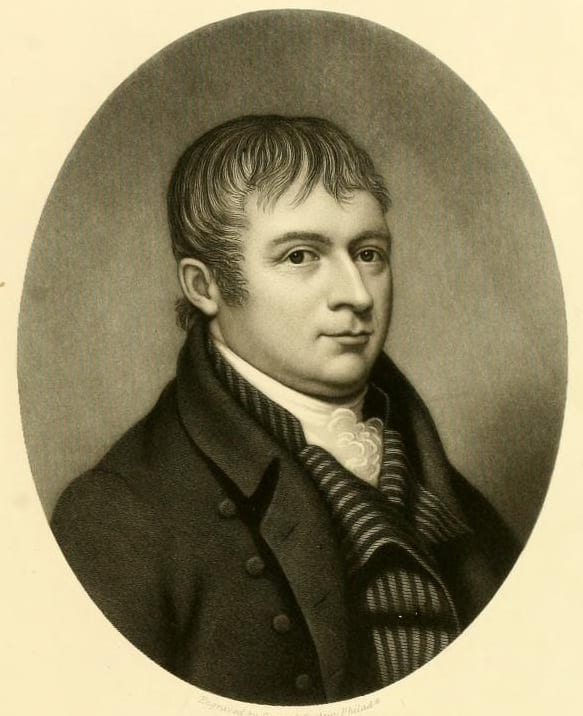

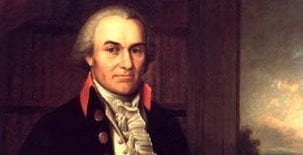

Richard Henry Lee (1732-1794) was a prominent Virginia statesman and delegate to the Continental Congress. During his time in Congress, Lee introduced three resolutions that shaped American history. The first, known as the “Lee Resolution,” called for independence from Britain and ultimately led to the Declaration of Independence. He also proposed resolutions to establish foreign alliances and draft a confederation plan. Lee did not attend the Constitutional Convention, but like fellow Virginian George Mason who did attend, he opposed ratifying the Constitution.

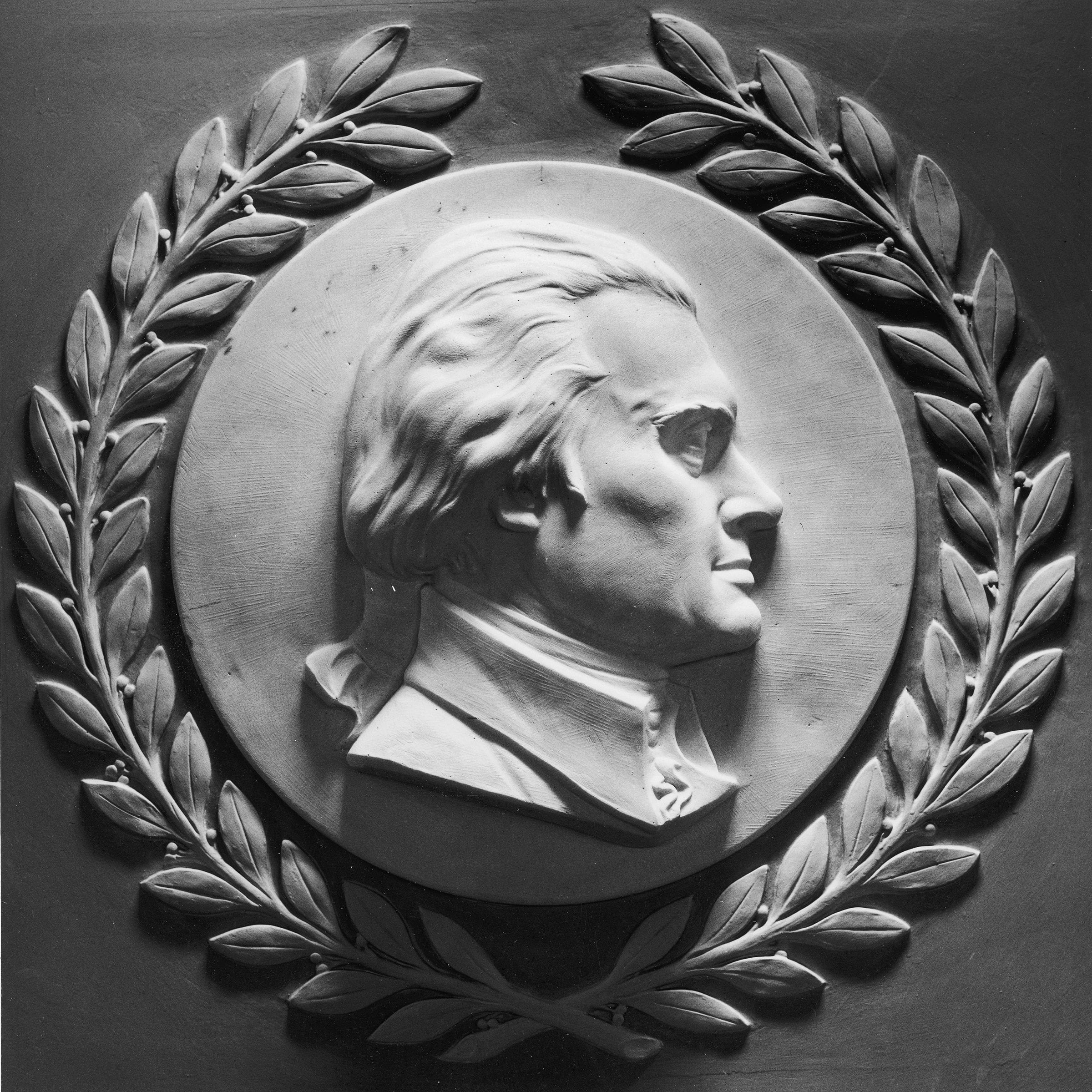

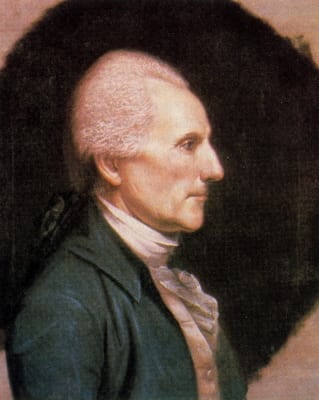

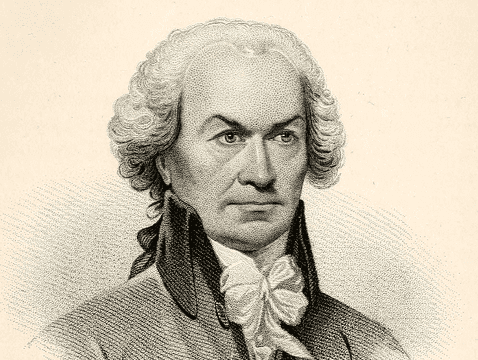

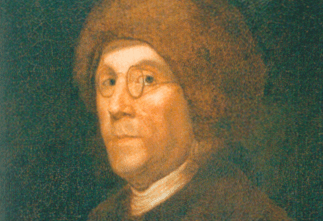

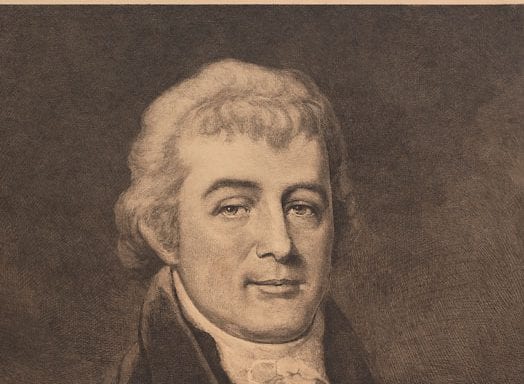

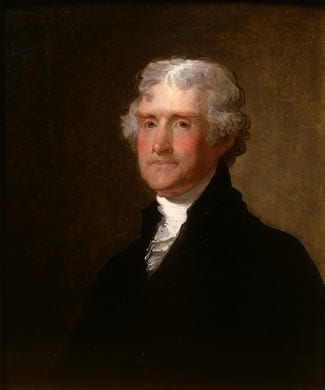

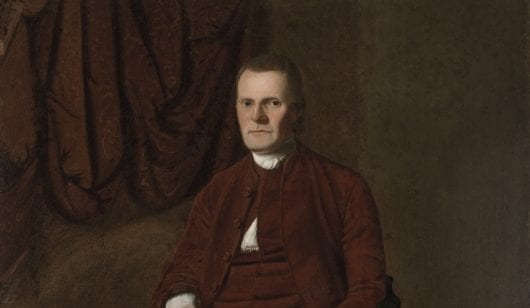

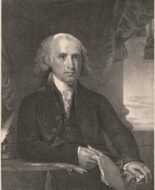

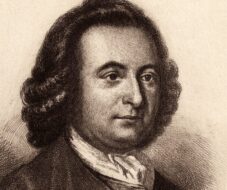

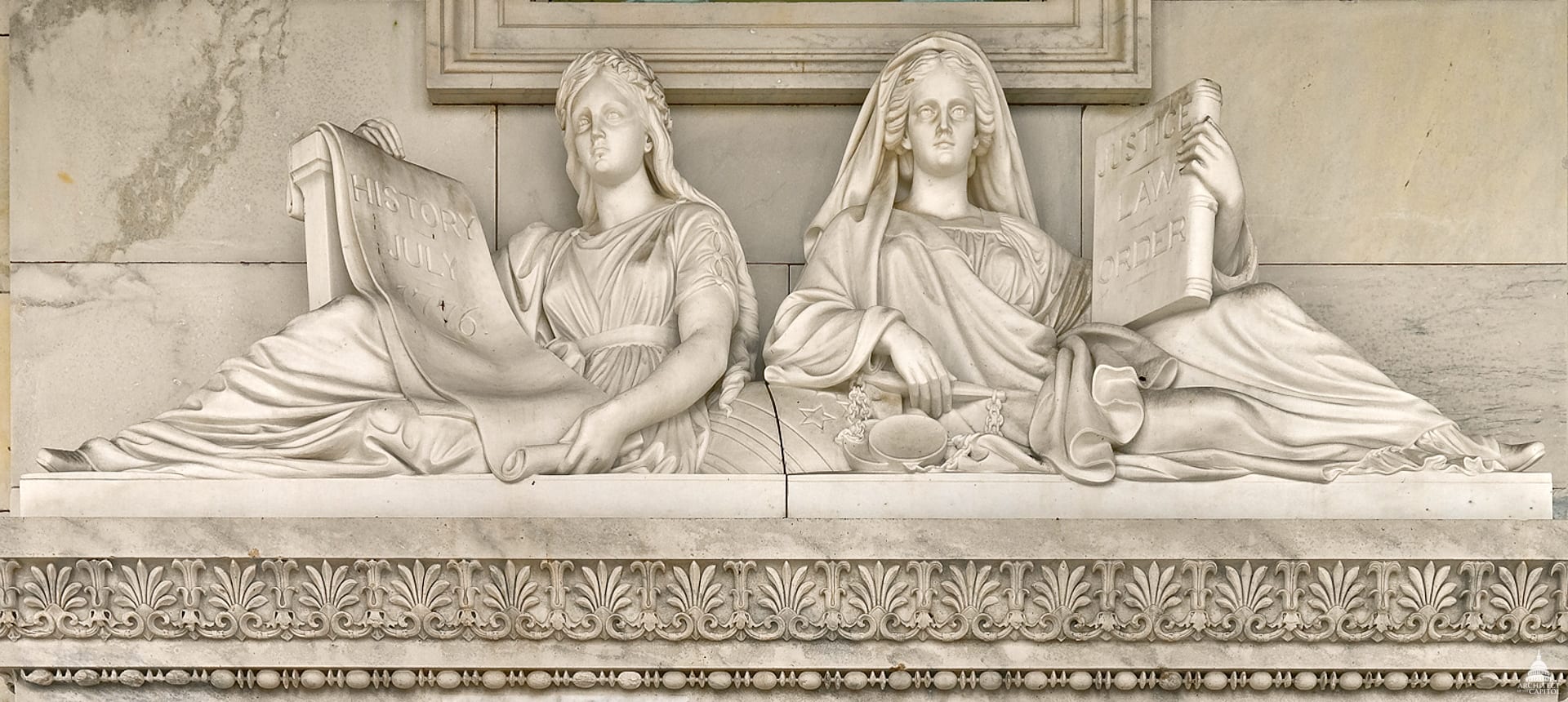

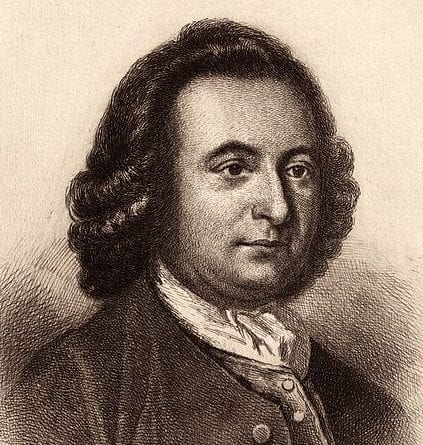

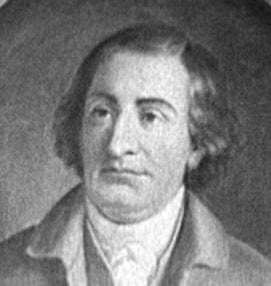

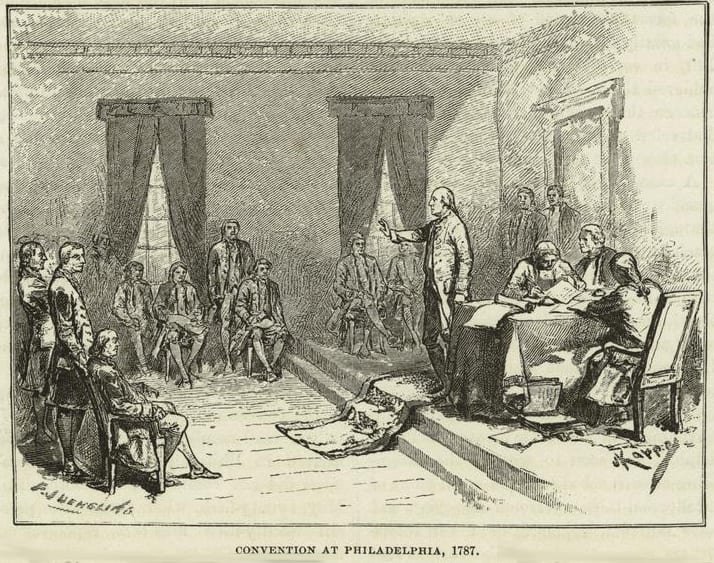

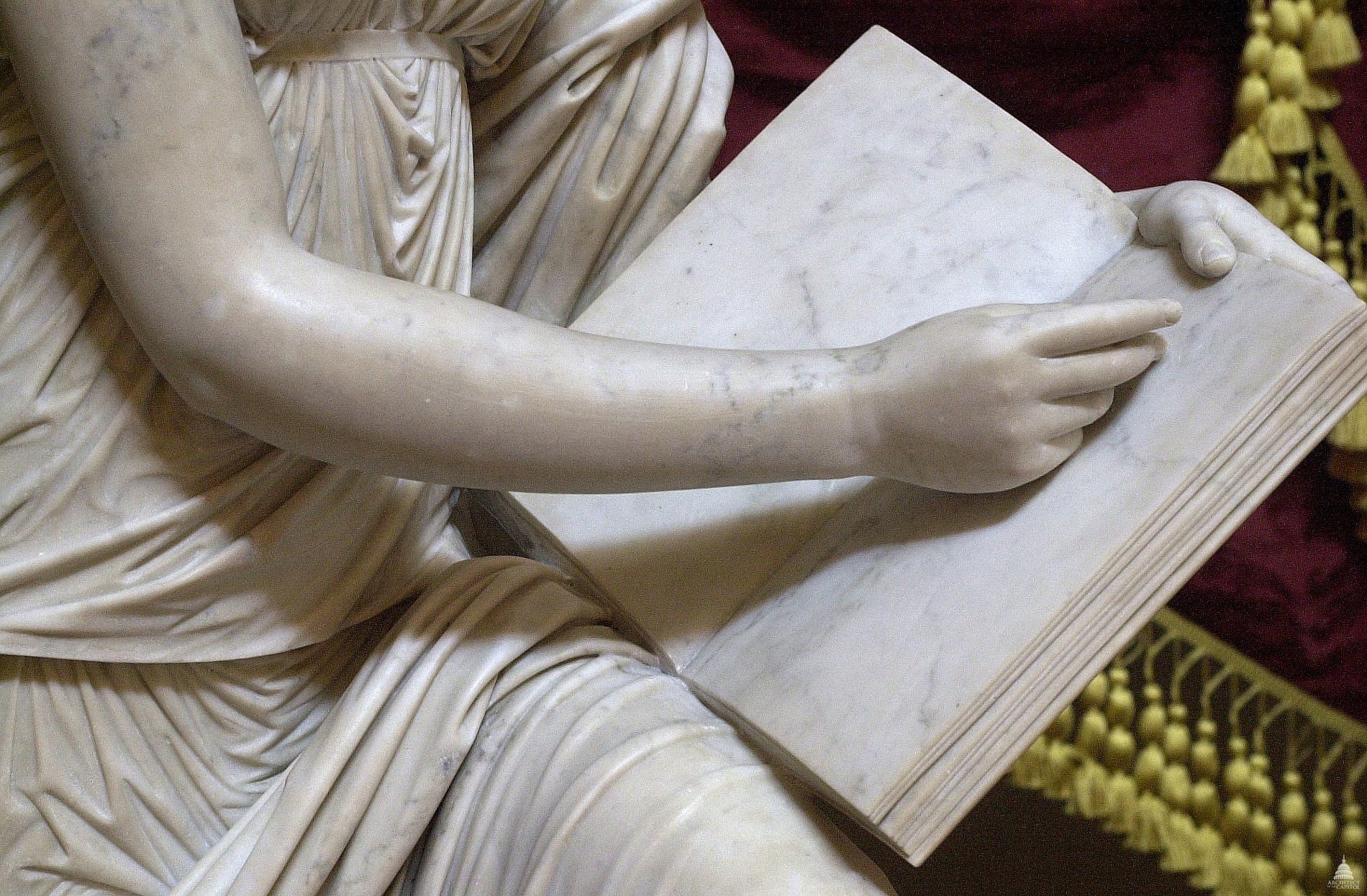

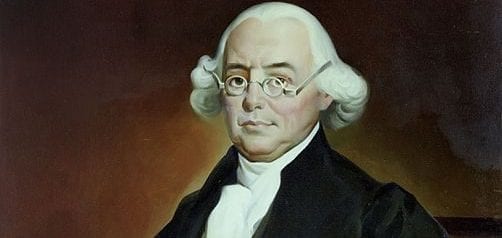

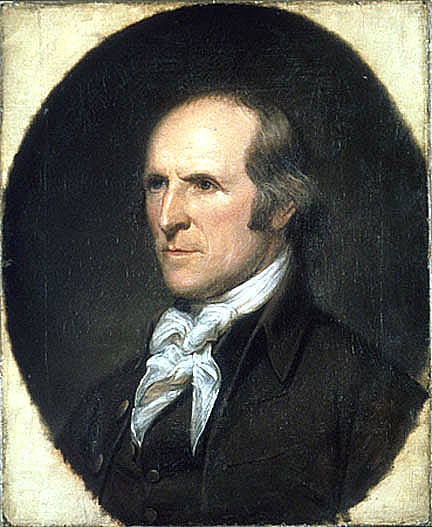

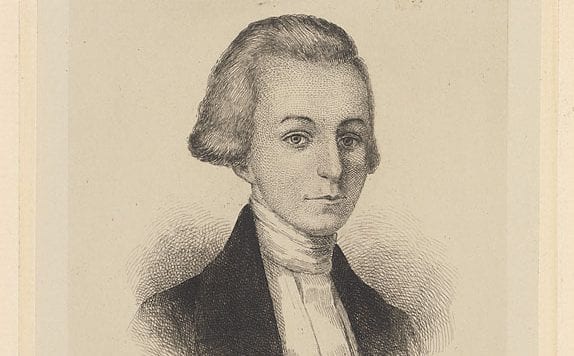

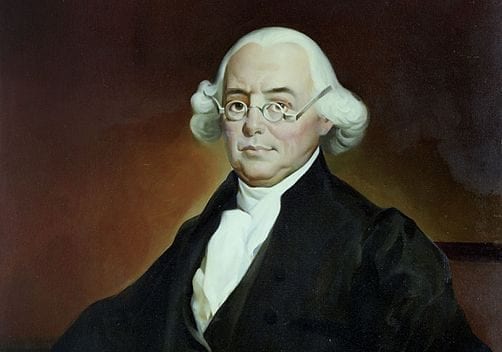

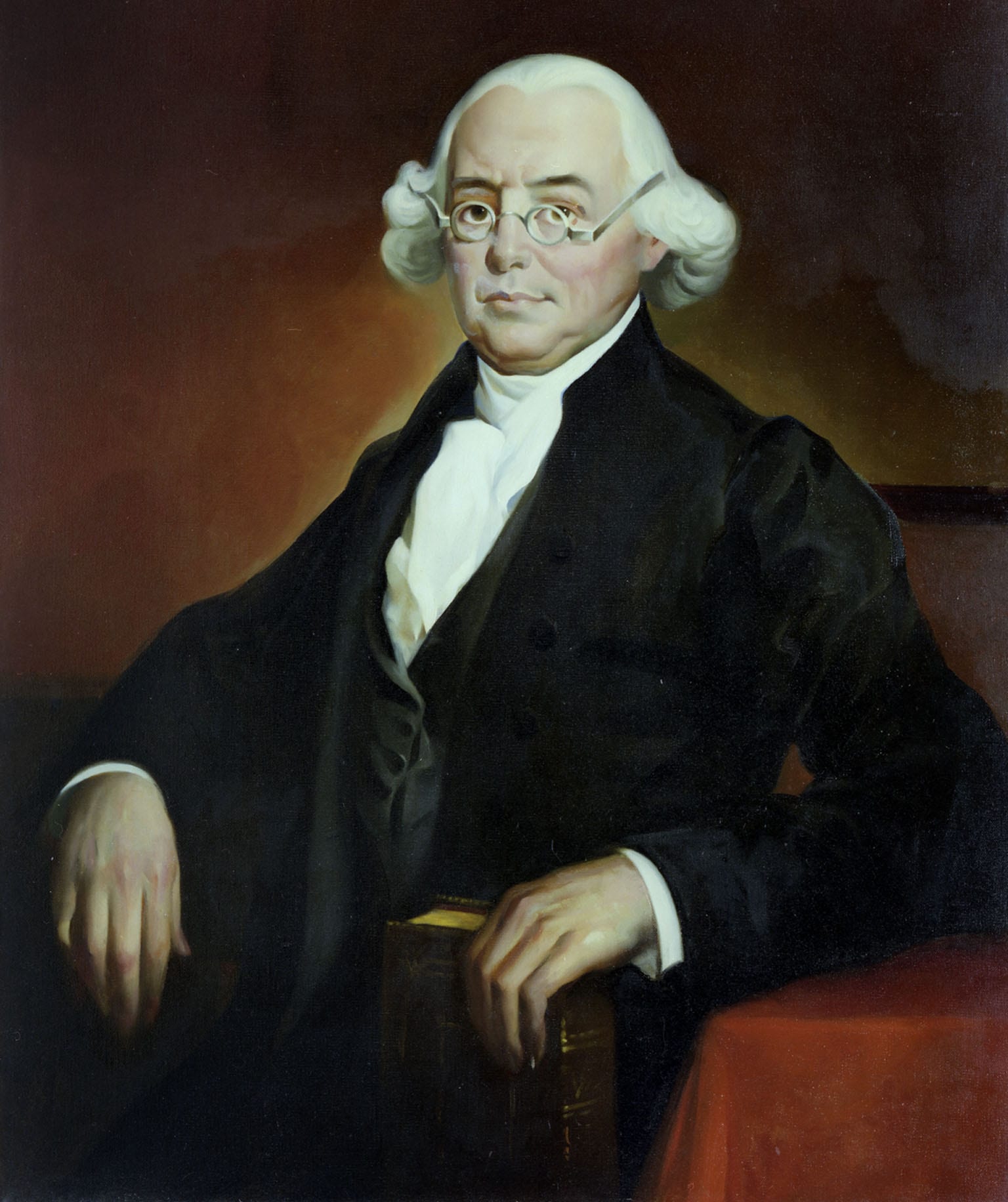

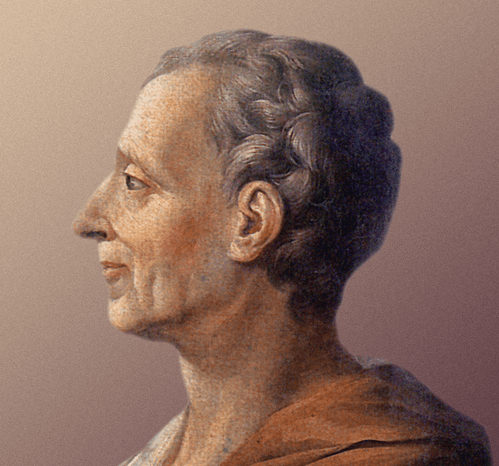

George Mason (1725-1792) held few formal political positions, but his beliefs and actions significantly impacted American politics. In 1776, Mason helped draft the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which influenced the Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights. As a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Mason was an active participant and speaker; however, he refused to sign the Constitution because it did not include a declaration of rights. Additionally, Mason was concerned about the potential for tyranny due to the powers granted to Congress and the federal judiciary.

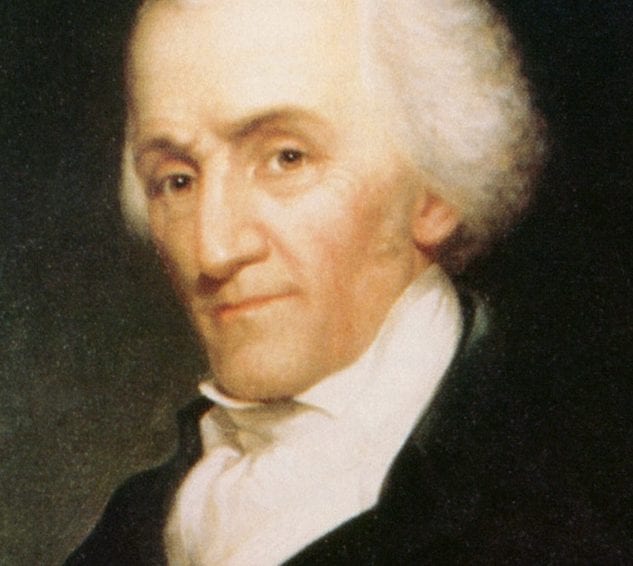

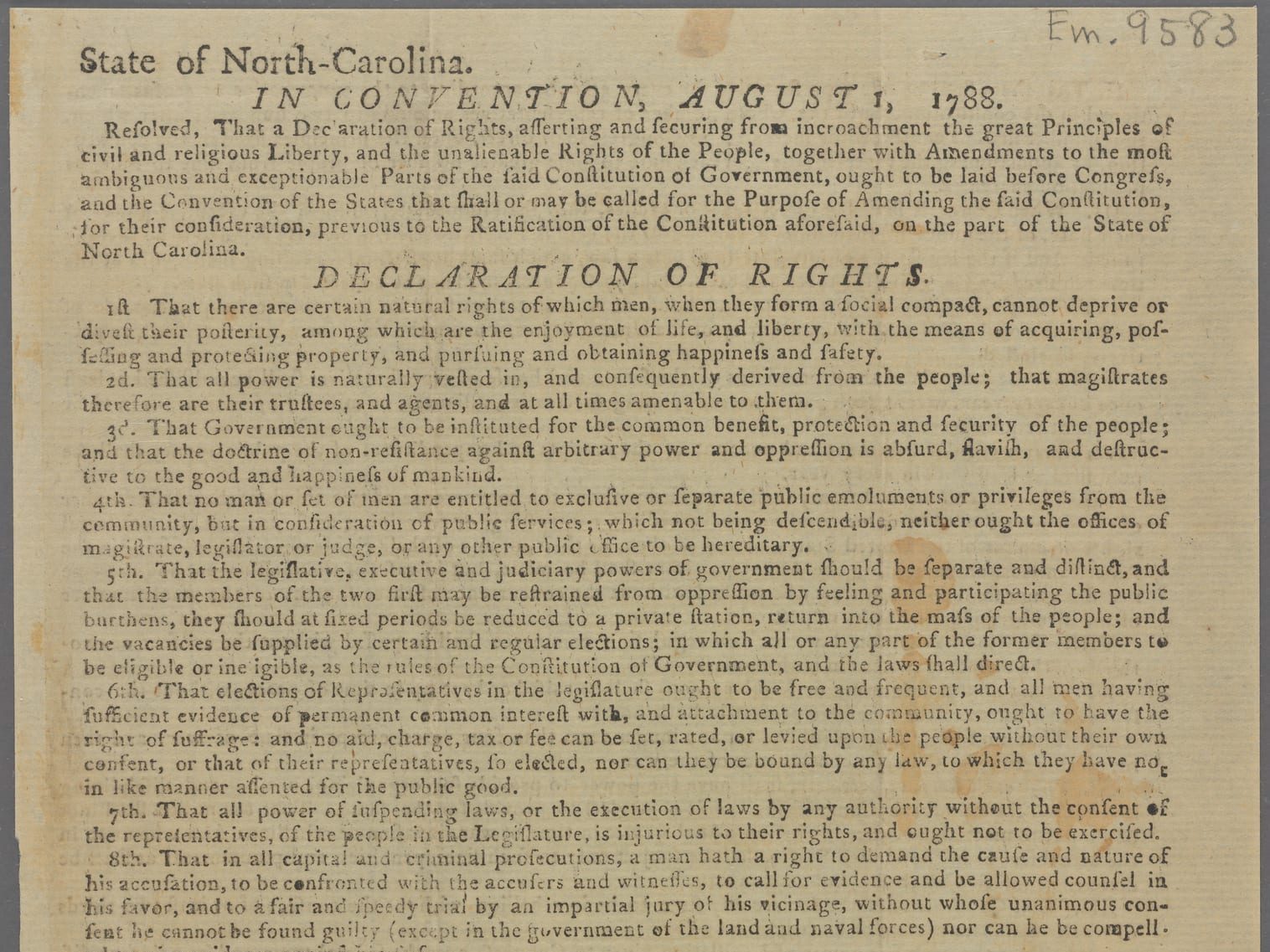

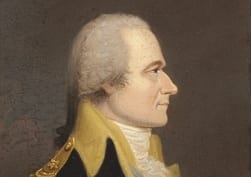

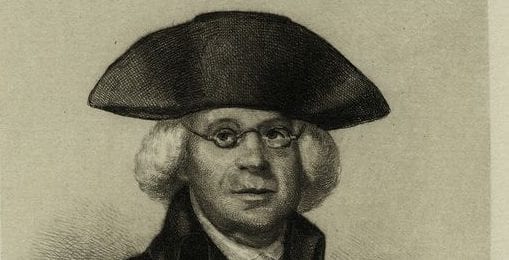

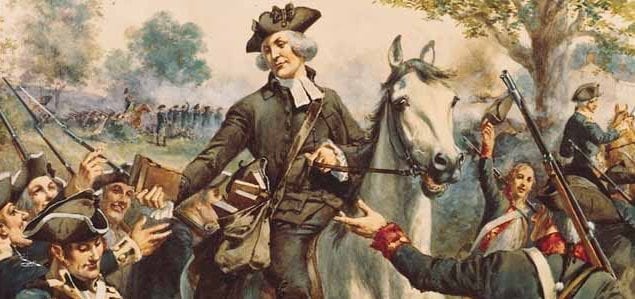

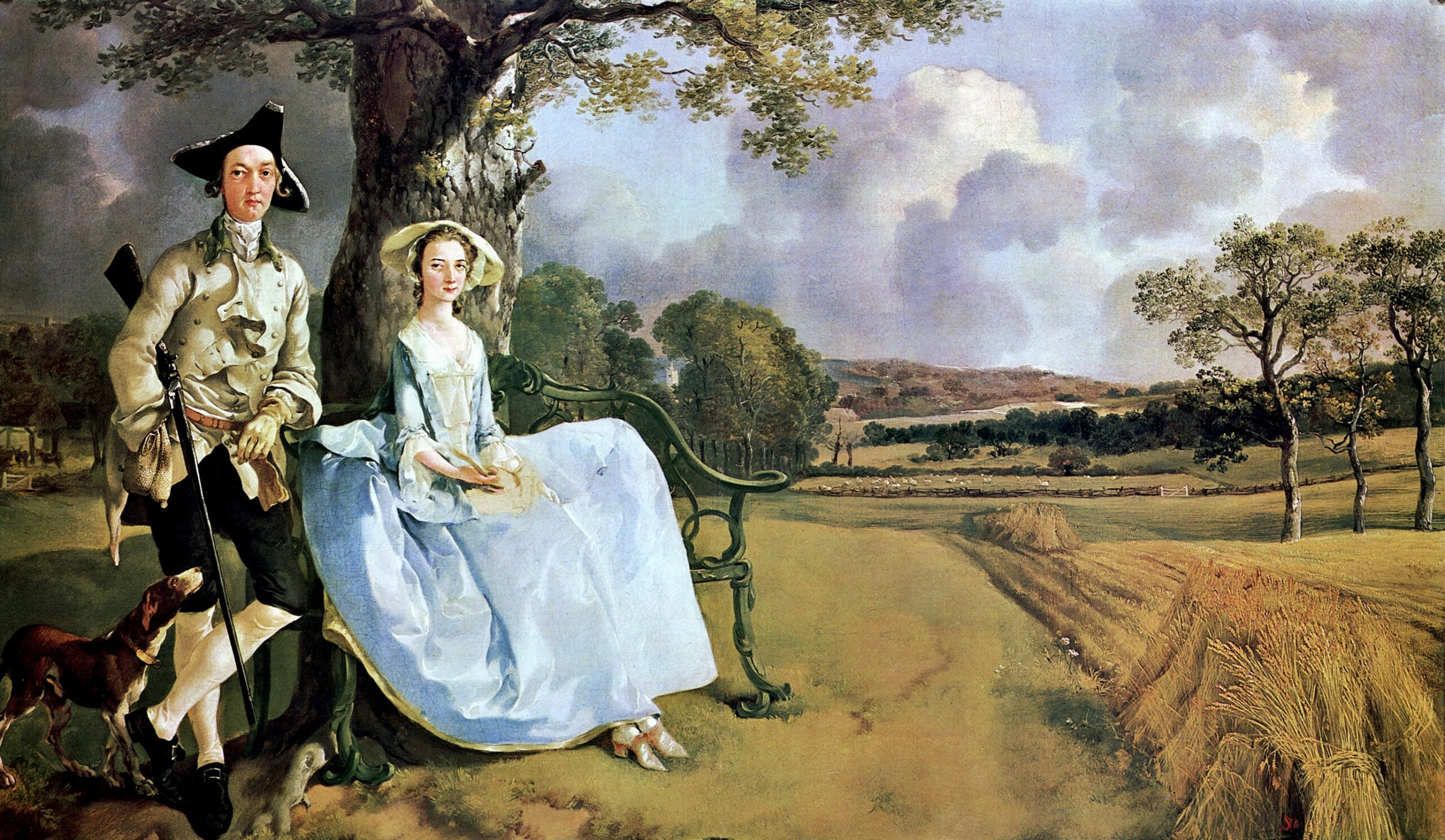

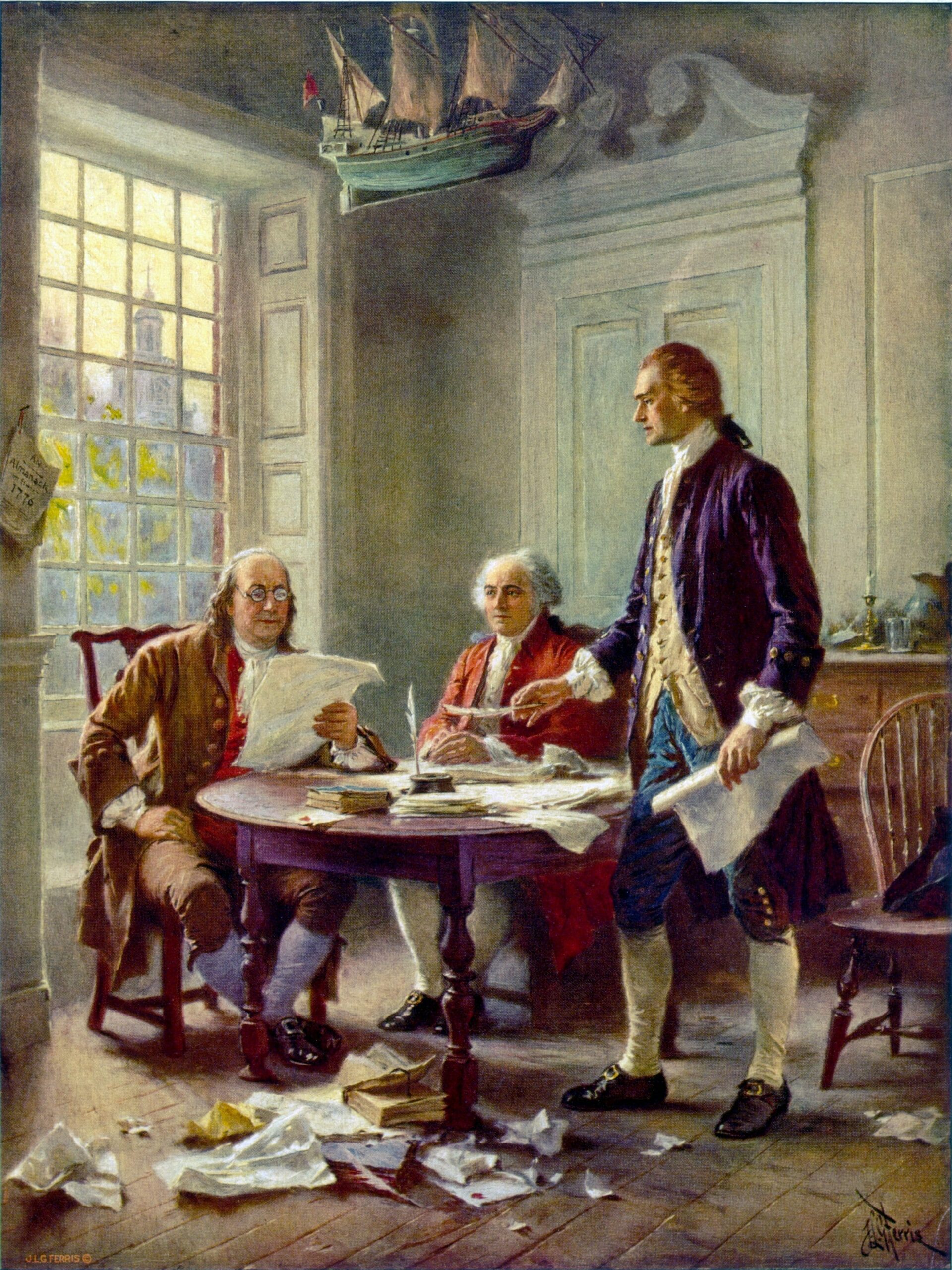

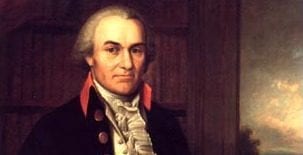

In this letter sent to Mason at the outset of the Convention, Lee expressed his concerns about granting greater power to the federal government. While other statesmen, including Virginians like George Washington (1732-1799) and Edmund Randolph (1753-1813), attributed the nation’s challenges under the Articles of Confederation to Congress’ lack of authority, Lee argued that moral failings were the leading cause of the nation’s discontent. He cautioned against “rash impatience” at the Convention, noting that many Americans were quick to advocate for increased congressional power to solve the nation’s problems.

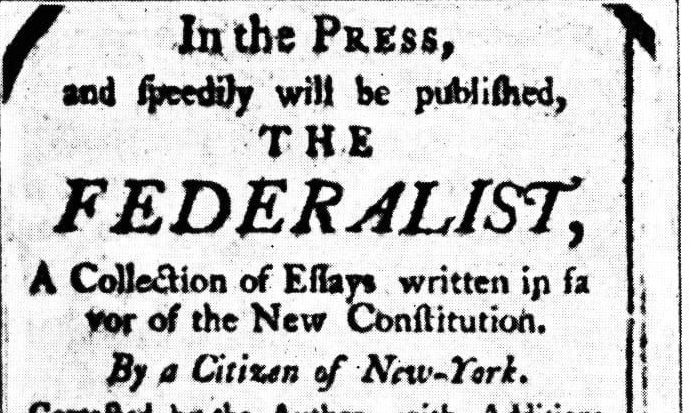

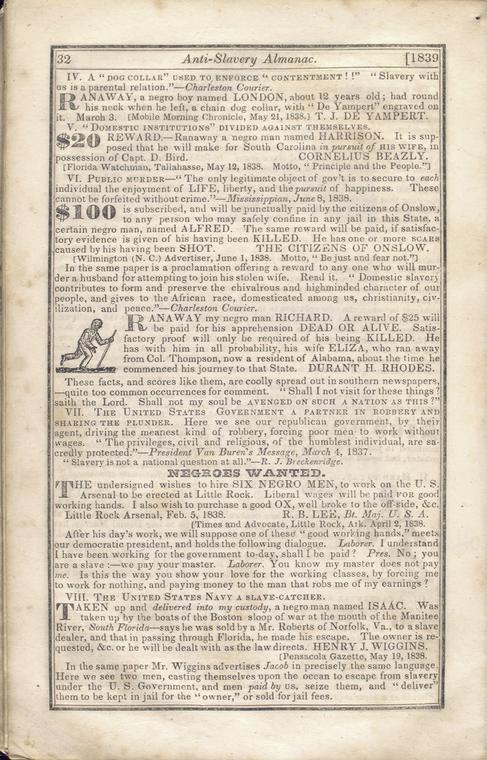

Lee expanded on this by criticizing the proposal to grant Congress the exclusive authority to issue paper money as a solution to the nation’s fiscal problems. He viewed it as a misguided idea promoted by deceitful individuals seeking to take advantage of “fools.” Lee argued that ill-conceived faith in paper money caused “constant ferment” and allowed fraud and speculation. Although he opposed granting Congress this power, Lee acknowledged that such a measure “would be a great step towards correcting morals.”

Lee’s letter highlighted his broader concerns about extensive constitutional changes and offered a cautionary perspective on constitutional reform, foreshadowing the subsequent ratification debates.

—Michelle Alderfer

Lee, Richard Henry. “Richard Henry Lee to George Mason.” Essay. In The Founders’ Constitution 1, edited by Philip B. Kurland and William R. Kenan, Jr., 170. University of Chicago Press, 1987. https://archive.org/details/foundersconstitu0000phil/page/170/mode/1up.

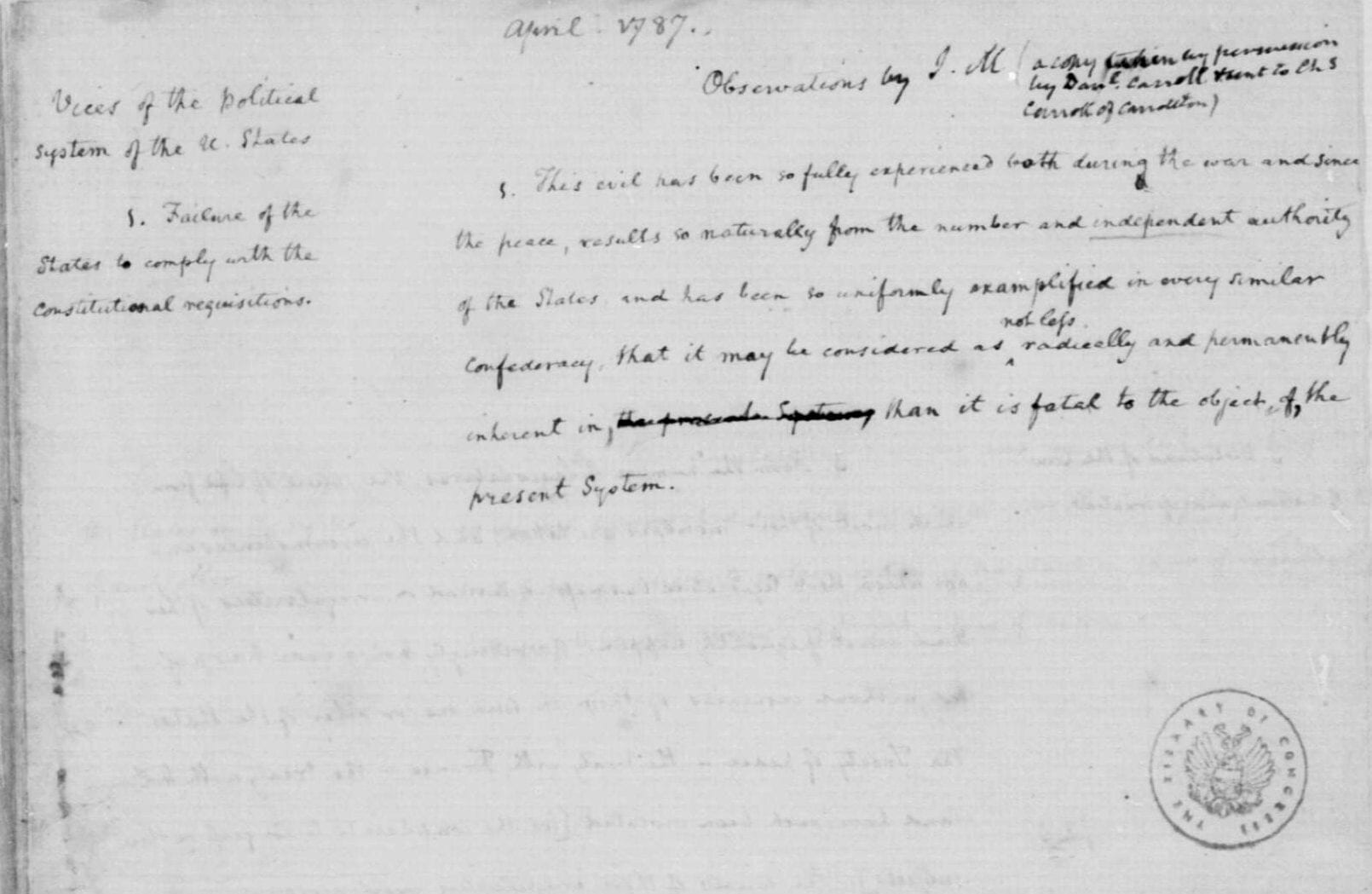

It has given me much pleasure to be informed that General Washington[1] and yourself have gone to the Convention. We may hope, from such efforts, that alterations beneficial will take place in our Federal Constitution, if it shall be found, on deliberate inquiry, that the evils now felt do flow from errors in that constitution; but, alas, sir, I fear it is more in vicious manners, than mistakes in form, that we must seek for the causes of the present discontent. The present causes of complaint seem to be, that Congress cannot command the money necessary for the just purposes of paying debts, or for supporting the federal government; and that they cannot make treaties of commerce, unless power unlimited, of regulating trade be given. The Confederation now gives right to name the sums necessary, and to apportion the quotas by a rule established. This rule is, unfortunately, very difficult of execution, and, therefore the recommendations of Congress on this subject have not been made in federal mode; so that States have thought themselves justified in non-compliance. If the rule were plain and easy, and refusal were then to follow demand, I see clearly, that no form of government whatever, short of force, will answer; for the same want of principle that produces neglect now, will do so under any change not supported by power compulsory; the difficulty certainly is, how to give this power in such manner as that it may only be used to good, and not abused to bad, purposes. Whoever shall solve this difficulty will receive the thanks of this and future generations. . . .

For now the cry is power, give Congress power.

Without reflecting that every free nation, that hath ever existed, has lost its liberty by the same rash impatience, and want of necessary caution. I am glad, however, to find, on this occasion, that so many gentlemen, of competent years, are sent to the Convention, for, certainly, “youth is the season of credulity, and confidence a plant of slow growth in an aged bosom.”. . .[2] It is that the right of making paper money shall be exclusively vested in Congress; such a right will be clearly within the spirit of the fourth section of the ninth article of the present confederation. . . . Knaves assure, and fools believe, that calling paper money, and making it tender, is the way to be rich and happy; thus the national mind is kept in constant ferment; and the public councils in continual disturbance by the intrigues of wicked men, for fraudulent purposes, for speculating designs. This would be a great step towards correcting morals, and suppressing legislative frauds, which, of all frauds, is the most hateful to society. Do you not think, sir, that it ought to be declared, by the new system, that any State act of legislation that shall contravene, or oppose, the authorized acts of Congress, or interfere with the expressed rights of that body, shall be ipso facto void, and of no force whatsoever? . . .

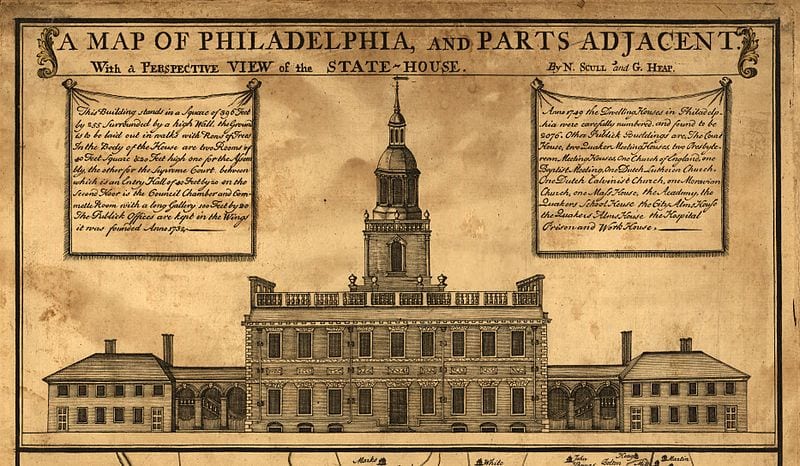

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)