Introduction

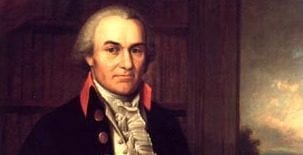

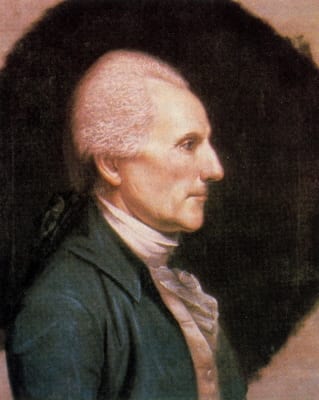

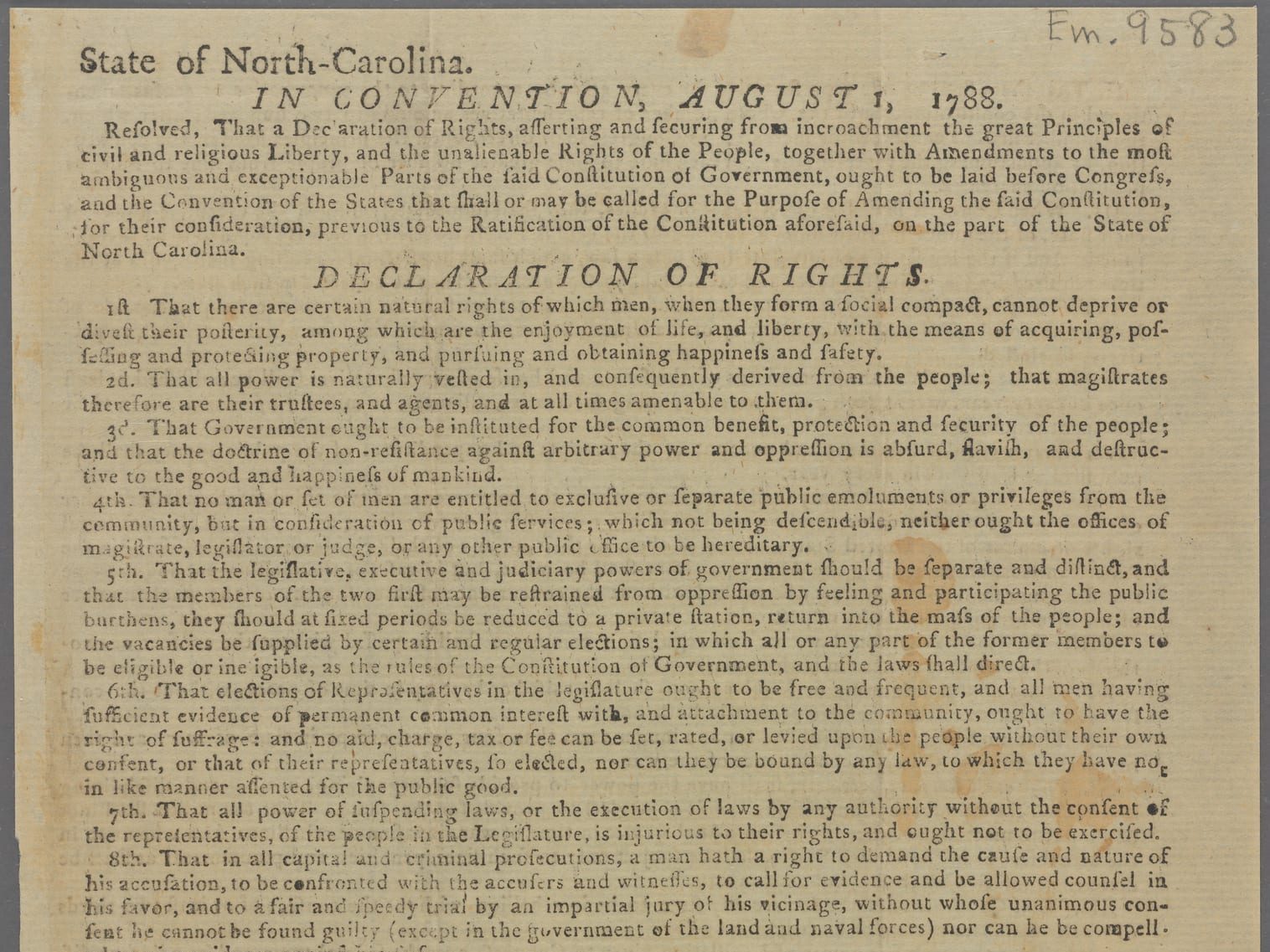

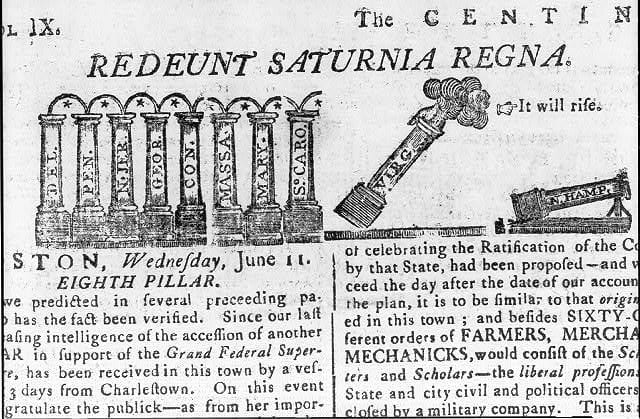

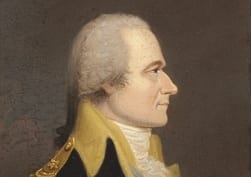

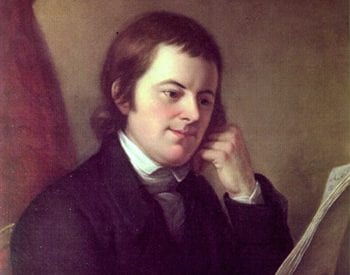

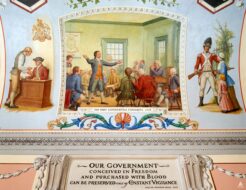

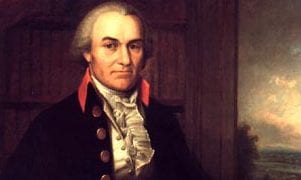

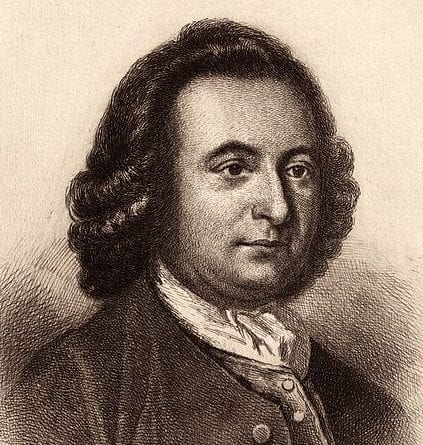

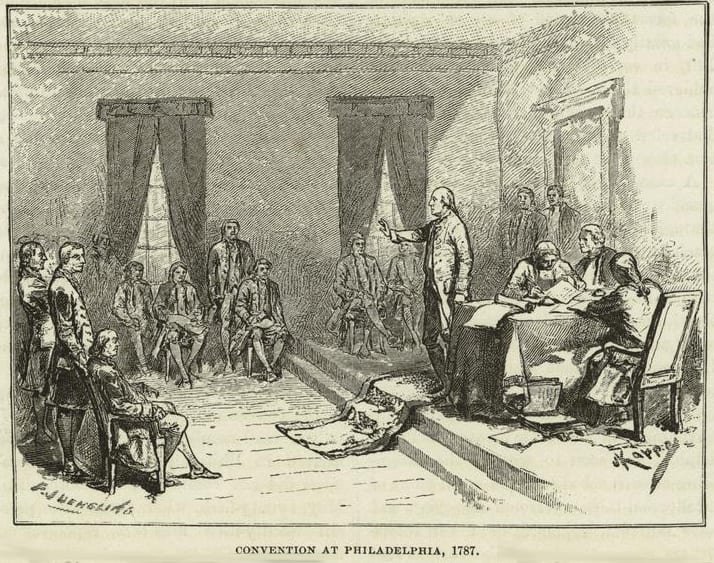

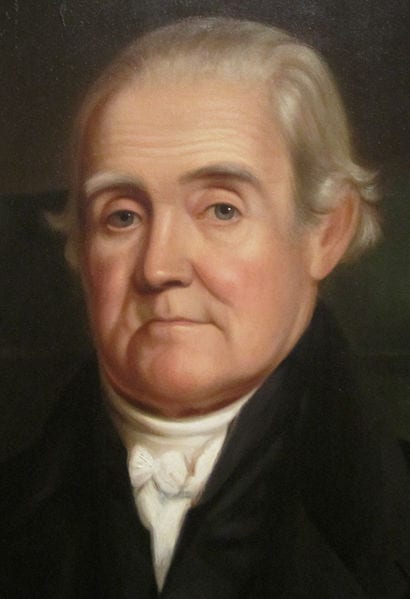

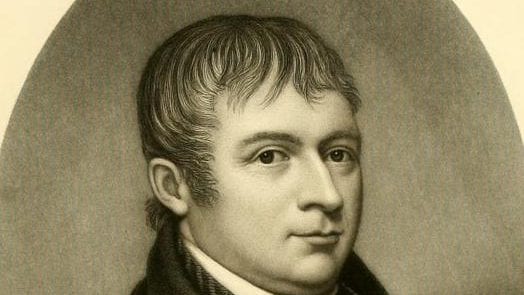

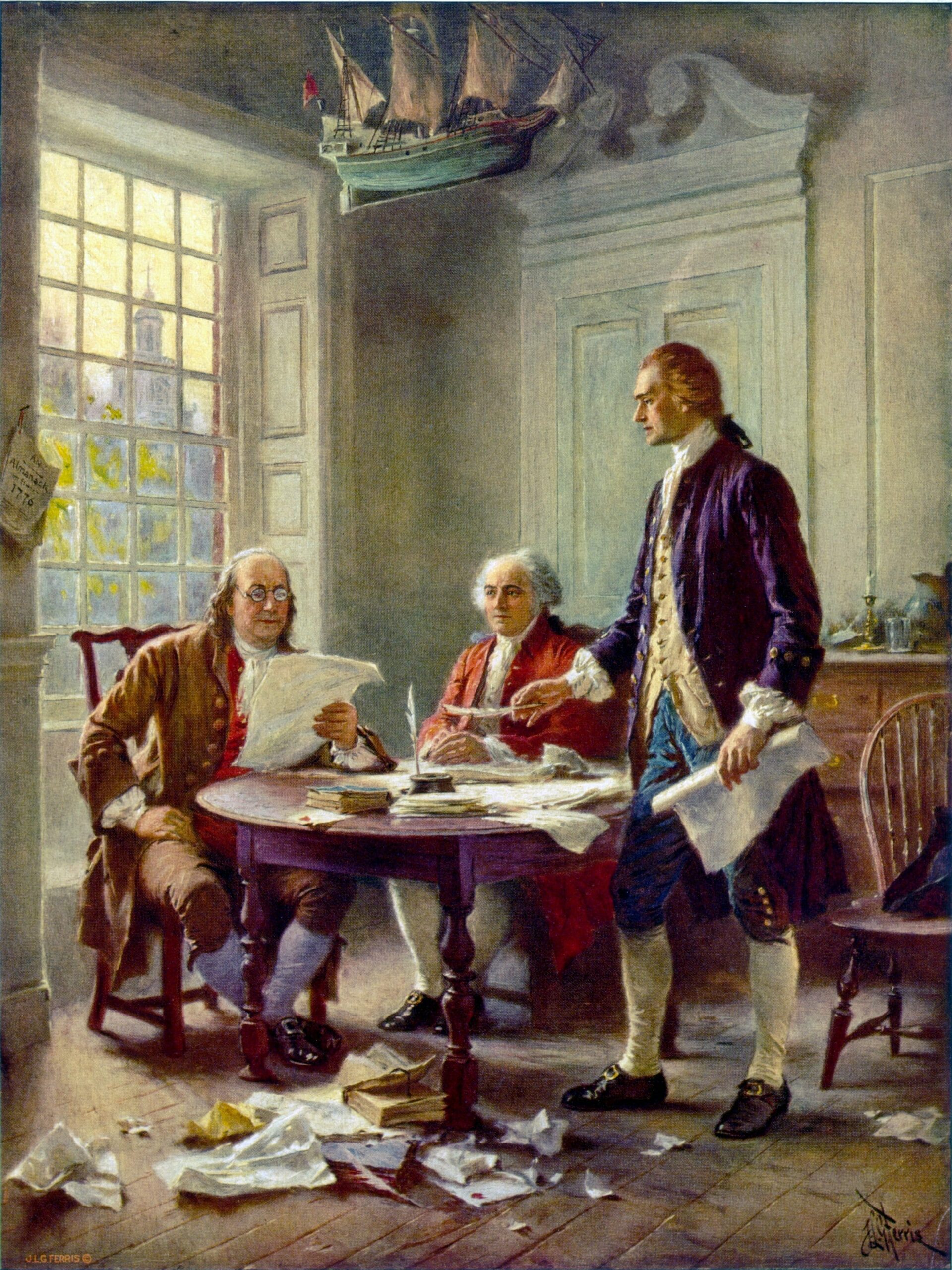

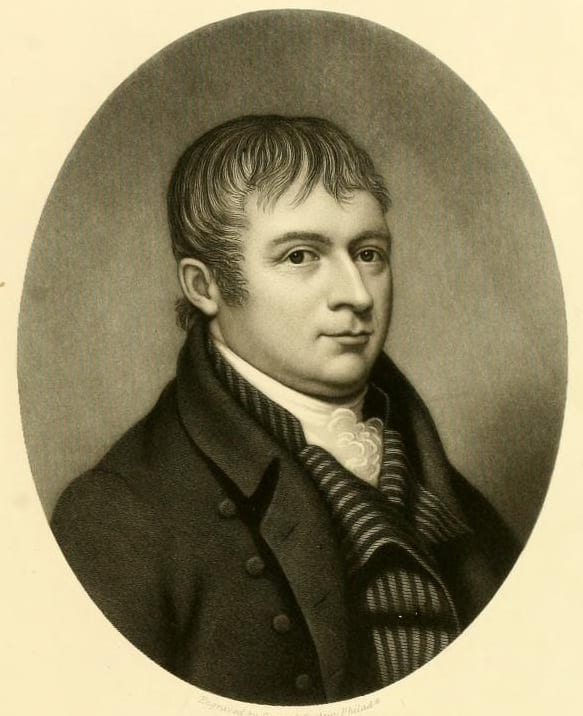

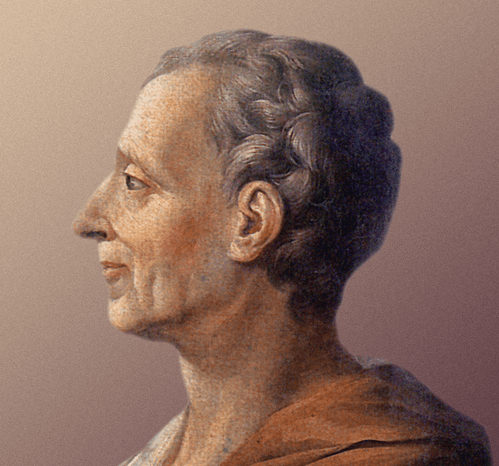

The June 6 vote on representation in the first branch (The Madison Sherman Exchange) was 8–3 in favor of the Virginia Plan’s provision that the people elect the members of this branch. (Connecticut, New Jersey, and South Carolina voted “no.”) On June 7, the delegates turned to the question created by the defeat of the Virginia Plan’s provision to have the second branch elected by the first branch. Instead, the delegates voted 11–0 that “the second branch of the national legislature [should] be elected by the individual legislatures.” But a state-based election of the second branch was only one part of the equation. Roger Sherman of Connecticut also wanted equal representation for each state in the second branch, in return for accepting popular representation in the first branch, which Connecticut had originally voted against.

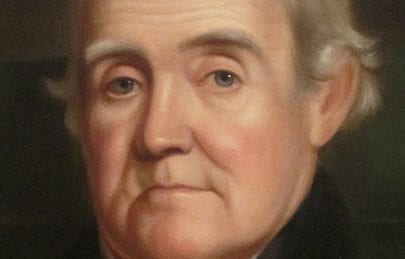

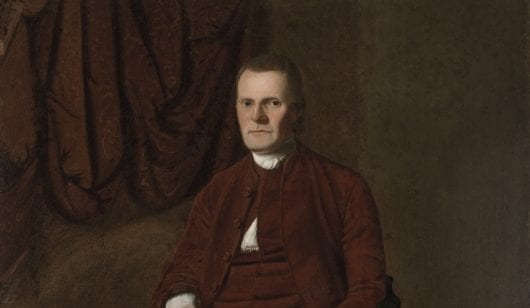

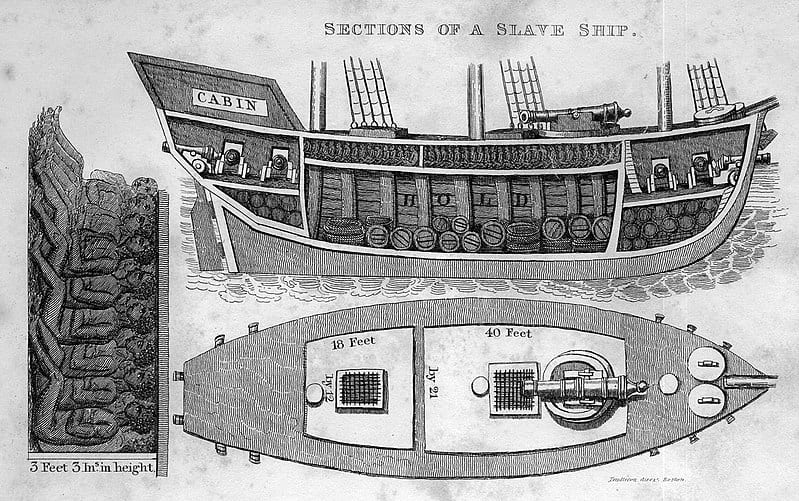

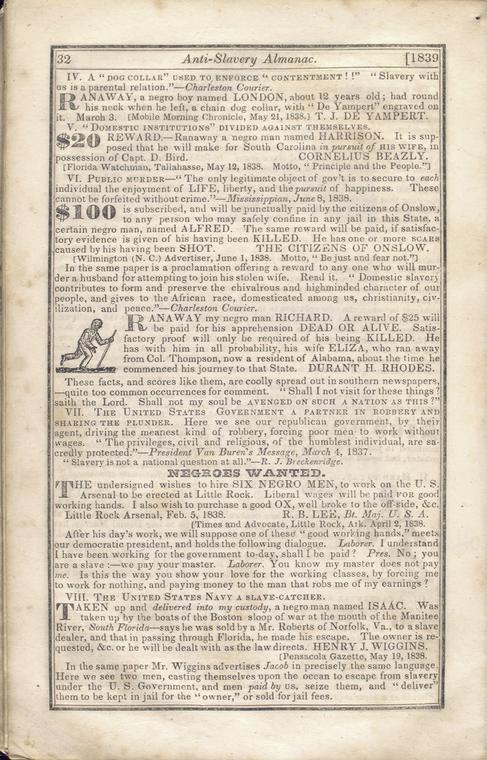

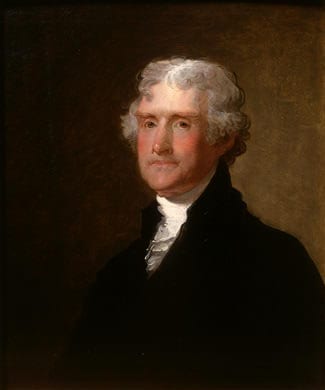

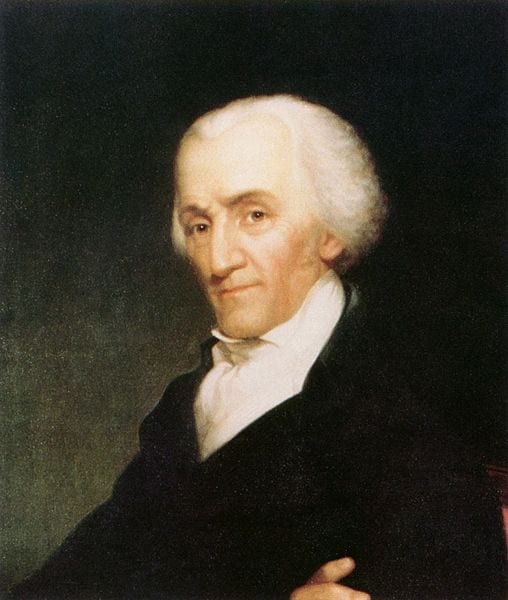

So on June 11, Sherman presented the delegates with a compromise: popular representation in the first branch in exchange for equal representation of the states in the second branch. But the delegates from South Carolina introduced a third dimension to the discussion over representation. “Money was power,” said Butler. And, therefore, should wealth not be represented as well as people and states? This wealth included property in slaves. The result was the introduction of a clause stating that those counted in the population to be represented should include free whites, even those bound in servitude, and “three-fifths of all other persons not comprehended in the foregoing description, except Indians not paying taxes, in each State.” The Three-Fifths Clause was included in the first branch on a 9–2 vote, but the vote to include it in the second branch barely passed, by a 6–5 vote. Connecticut, New York, and Maryland were willing to accept popular representation plus three-fifths in the first branch but, along with New Jersey and Delaware, insisted on equal representation for the states in the second branch.

—Gordon Lloyd

Source: Gordon Lloyd, ed., Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 by James Madison, a Member (Ashland, OH: Ashbrook Center, 2014), 65–72.

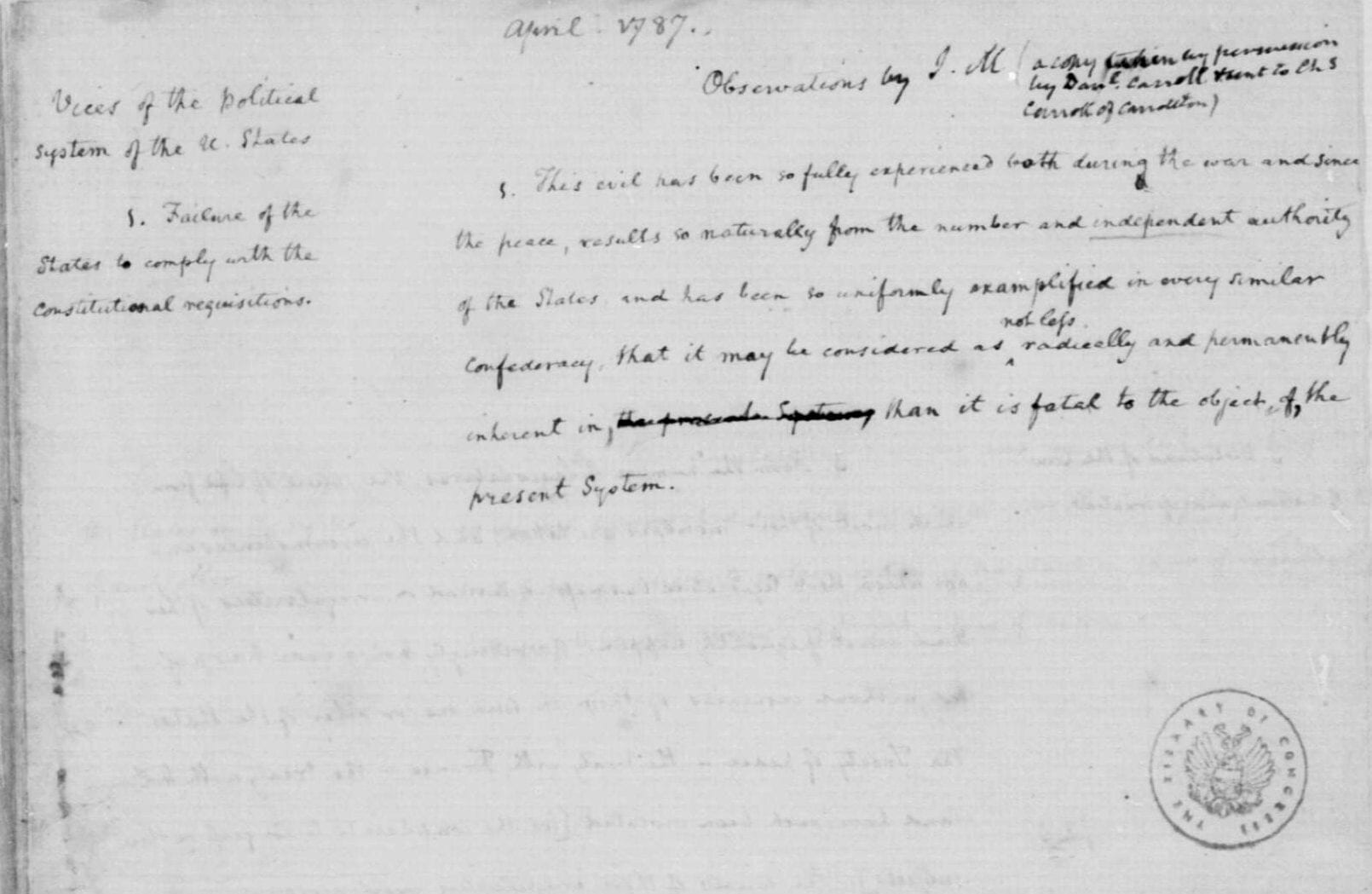

In Committee of the Whole, – The clause concerning the rule of suffrage in the National Legislature, postponed on Saturday, was resumed.

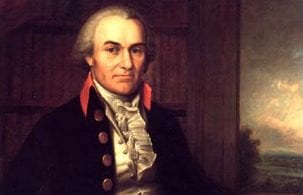

Mr. SHERMAN proposed, that the proportion of suffrage in the first branch should be according to the respective numbers of free inhabitants; and that in the second branch, or Senate, each State should have one vote and no more. He said, as the States would remain possessed of certain individual rights, each State ought to be able to protect itself; otherwise, a few large States will rule the rest. The House of Lords in England, he observed, had certain particular rights under the Constitution, and hence they have an equal vote with the House of Commons, that they may be able to defend their rights.

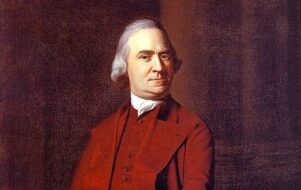

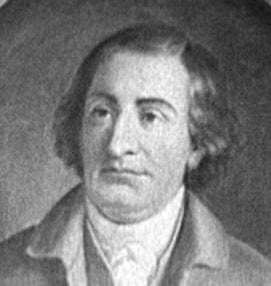

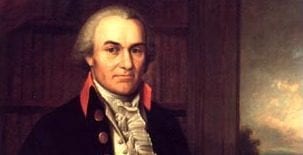

Mr. RUTLEDGE proposed, that the proportion of suffrage in the first branch should be according to the quotas of contribution. The justice of this rule, he said, could not be contested. Mr. BUTLER urged the same idea; adding, that money was power; and that the States ought to have weight in the government in proportion to their wealth.

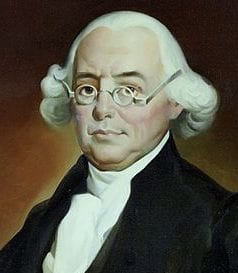

Mr. KING and Mr. WILSON, in order to bring the question to a point, moved, “that the right of suffrage in the first branch of the National Legislature ought not to be according to the rule established in the Articles of Confederation, but according to some equitable ratio of representation.” The clause, so far as it related to suffrage in the first branch, was postponed, in order to consider this motion.

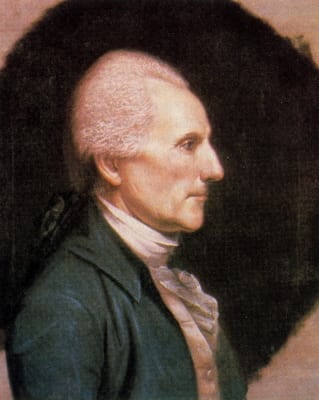

Mr. DICKINSON contended for the actual contributions of the States, as the rule of their representation and suffrage in the first branch. By thus connecting the interests of the States with their duty, the latter would be sure to be performed.

Mr. KING remarked, that it was uncertain what mode might be used in levying a national revenue; but that it was probable, imposts would be one source of it. If the actual contributions were to be the rule, the non-importing States, as Connecticut and New Jersey, would be in a bad situation, indeed. It might so happen that they would have no representation. This situation of particular States had been always one powerful argument in favor of the five per cent. impost. . . .

On the question for agreeing to Mr. KING’S and Mr. WILSON’S motion, it passed in the affirmative, – Massachusetts, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, aye – 7; New York, New Jersey, Delaware, no – 3; Maryland, divided.

It was then moved by Mr. RUTLEDGE, seconded by Mr. BUTLER, to add to the words, “equitable ratio of representation,” at the end of the motion just agreed to, the words “according to the quotas of contribution.”

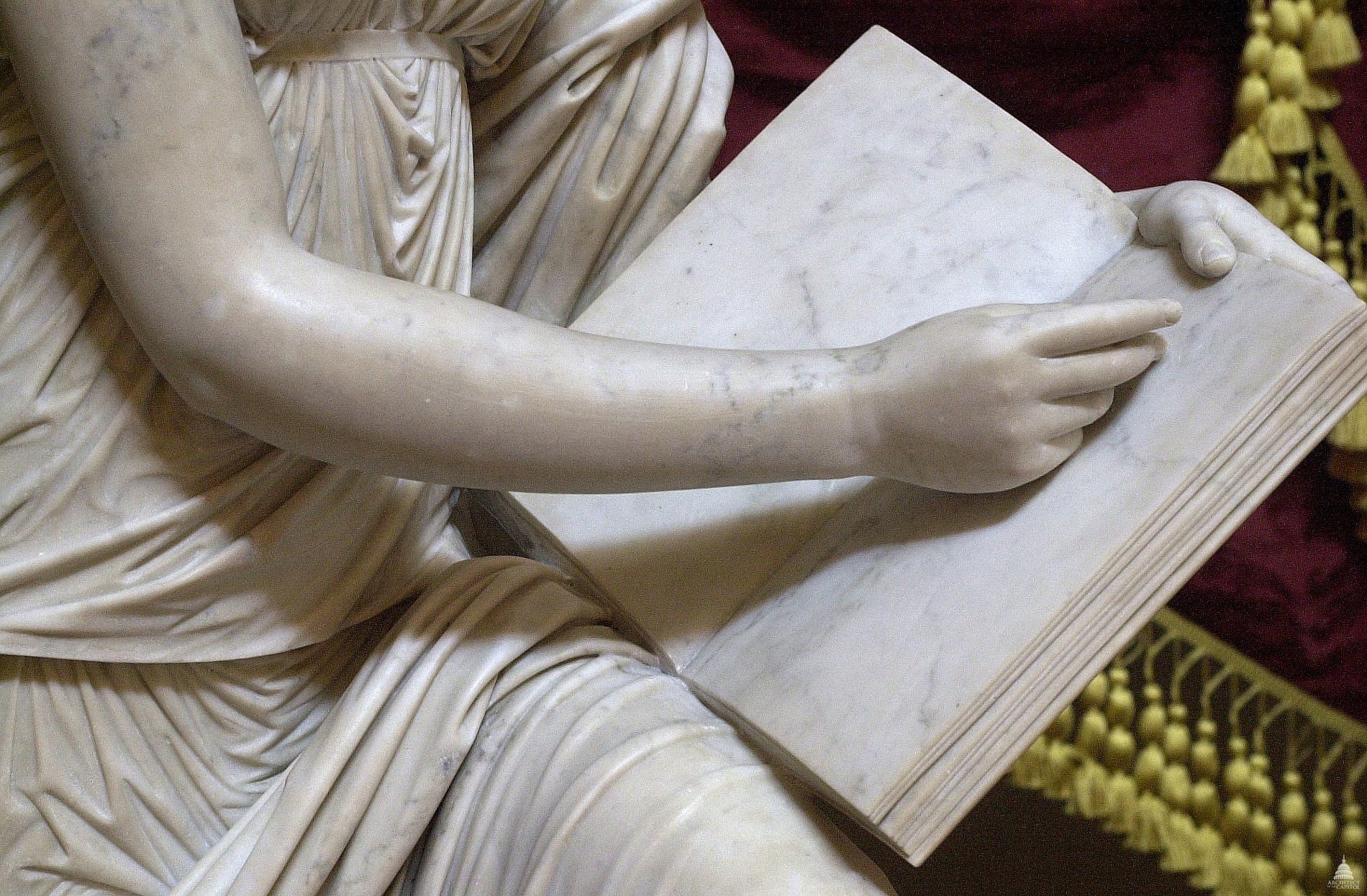

On motion of Mr. WILSON, seconded by Mr. PINCKNEY, this was postponed; in order to add, after the words, “equitable ratio of representation,” the words following: “in proportion to the whole number of white and other free citizens and inhabitants of every age, sex and condition, including those bound to servitude for a term of years, and three-fifths of all other persons not comprehended in the foregoing description, except Indians not paying taxes, in each State” – this being the rule in the act of Congress, agreed to by eleven States, for apportioning quotas of revenue on the States, and requiring a census only every five, seven, or ten years.

Mr. GERRY thought property not the rule of representation. Why, then, should the blacks, who were property in the South, be in the rule of representation more than the cattle and horses of the North?

On the question, – Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, aye – 9; New Jersey, Delaware, no – 2.

Mr. SHERMAN moved, that a question be taken, whether each State shall have one vote in the second branch. Every thing, he said, depended on this. The smaller States would never agree to the plan on any other principle than an equality of suffrage in this branch. Mr. ELLSWORTH seconded the motion.

On the question for allowing each State one vote in the second branch, – Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, aye – 5; Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, no – 6.

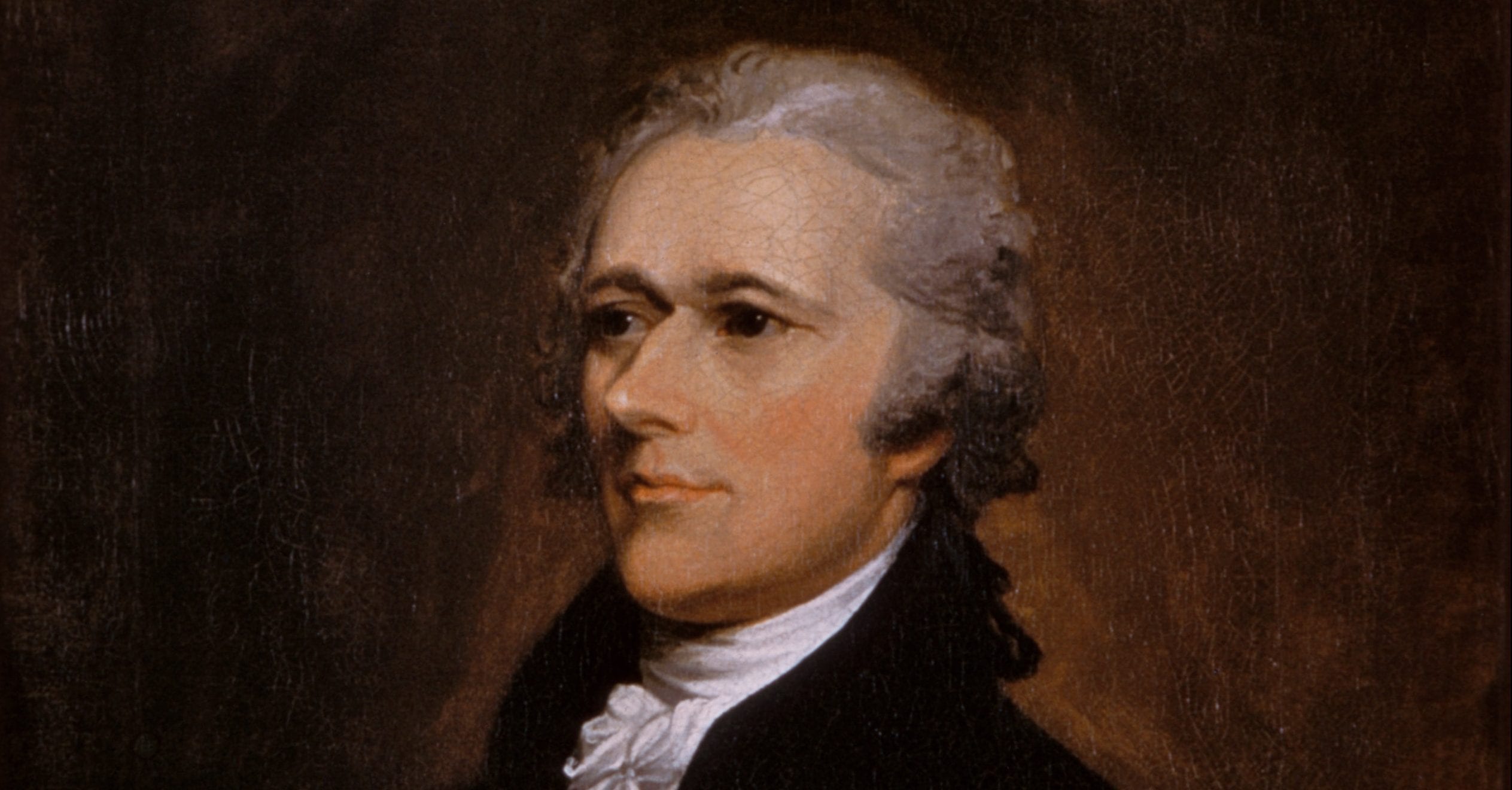

Mr. WILSON and Mr. HAMILTON moved, that the right of suffrage in the second branch ought to be according to the same rule as in the first branch.

On this question for making the ratio of representation, the same in the second as in the first branch, it passed in the affirmative, – Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, aye – 6; Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, no – 5.

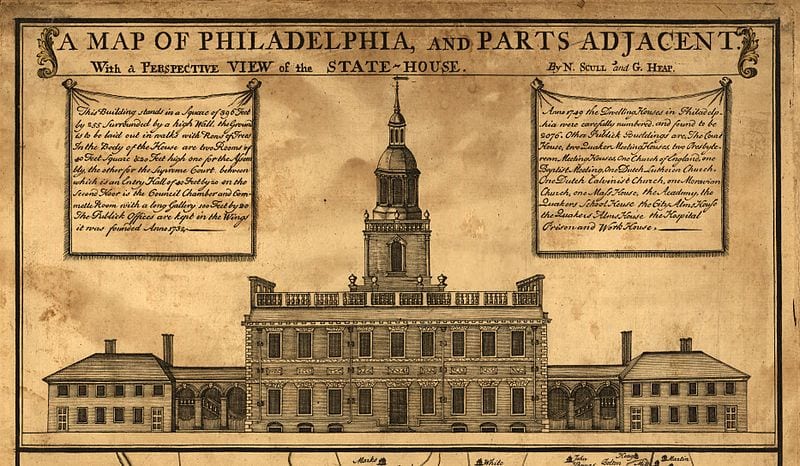

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)