No related resources

Introduction

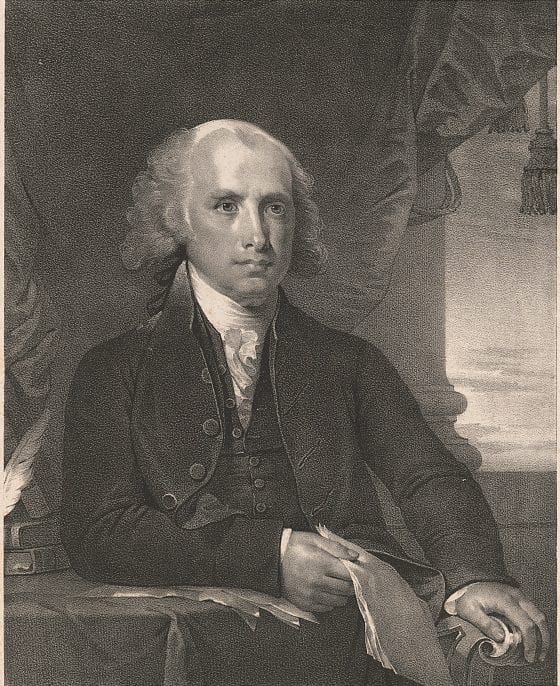

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 were issued in response to the Alien and Sedition Acts, four laws Congress enacted in June and July of 1798 that, among other things, authorized the detention and deportation of noncitizens and punished statements critical of the federal government and government officials. Although their authorship was not disclosed at the time, James Madison took the lead in crafting the Virginia Resolutions adopted by the Virginia General Assembly, and Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the Kentucky Resolutions enacted by the Kentucky General Assembly.

At the heart of the Virginia Resolutions was the claim that state officials had a role to play in determining when the federal government had exceeded its authority and bringing federal officials back within their proper limits. The Virginia General Assembly grounded this claim in the theory that the Constitution was a compact, arguing that the federal government’s powers resulted from “the compact to which the states are parties,” and federal acts are legitimate only in so far as they are enacted pursuant to powers “enumerated in that compact.”

The crucial issue under consideration was what actions state governments were authorized to take upon determining that the federal government had exceeded its legitimate authority. How might a state “interpose for arresting” the execution of federal law? Notably, the Virginia Resolutions did not claim, as the Kentucky Resolutions did, that a single state could declare a federal act null and void and of no effect. Instead, the Virginia Resolutions emphasized the importance of collective state action. The Kentucky Resolutions went further and declared each of the Alien and Sedition Acts to be “not law but utterly void and of no force”. For the response of other states to Virginia’s Resolutions, see Response to the Virginia Resolutions.

Source: “Virginia Resolutions, 21 December 1798,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-17-02-0128.

Resolved, that the General Assembly of Virginia doth unequivocally express a firm resolution to maintain and defend the Constitution of the United States, and the Constitution of this state, against every aggression, either foreign or domestic, and that they will support the government of the United States in all measures warranted by the former.

That this Assembly most solemnly declares a warm attachment to the Union of the States, to maintain which it pledges all its powers; and that for this end, it is their duty to watch over and oppose every infraction of those principles, which constitute the only basis of that union, because a faithful observance of them can alone secure its existence, and the public happiness.

That this Assembly doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that it views the powers of the federal government as resulting from the compact to which the states are parties; as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting that compact; as no farther valid than they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact, and that in case of a deliberate, palpable and dangerous exercise of other powers not granted by the said compact, the states who are parties there-to have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them.

That the General Assembly doth also express its deep regret that a spirit has in sundry instances been manifested by the federal government, to enlarge its powers by forced constructions of the constitutional charter which defines them; and that indications have appeared of a design to expound certain general phrases (which having been copied from the very limited grant of powers in the former articles of confederation were the less liable to be misconstrued) so as to destroy the meaning and effect of the particular enumeration, which necessarily explains and limits the general phrases; and so as to consolidate the states by degrees into one sovereignty, the obvious tendency and inevitable consequence of which would be to transform the present republican system of the United States into an absolute, or at best a mixed monarchy.

That the General Assembly doth particularly protest against the palpable and alarming infractions of the Constitution in the two late cases of the “alien and sedition acts,” passed at the last session of Congress; the first of which exercises a power nowhere delegated to the federal government; and which by uniting legislative and judicial powers to those of executive, subverts the general principles of free government, as well as the particular organization and positive provisions of the federal Constitution; and the other of which acts exercises in like manner a power not delegated by the Constitution, but on the contrary expressly and positively forbidden by one of the amendments thereto;1 a power which more than any other ought to produce universal alarm, because it is levelled against that right of freely examining public characters and measures, and of free communication among the people thereon, which has ever been justly deemed the only effectual guardian of every other right.

That this state having by its convention which ratified the federal Constitution, expressly declared, “that among other essential rights, the liberty of conscience and of the press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified by any authority of the United States”2 and from its extreme anxiety to guard these rights from every possible attack of sophistry or ambition, having with other states recommended an amendment for that purpose, which amendment was in due time annexed to the Constitution, it would mark a reproachful inconsistency and criminal degeneracy, if an indifference were now shown to the most palpable violation of one of the rights thus declared and secured, and to the establishment of a precedent which may be fatal to the other.

That the good people of this Commonwealth having ever felt and continuing to feel the most sincere affection for their brethren of the other states, the truest anxiety for establishing and perpetuating the union of all, and the most scrupulous fidelity to that Constitution which is the pledge of mutual friendship and the instrument of mutual happiness, the General Assembly doth solemnly appeal to the like dispositions of the other states, in confidence that they will concur with this Commonwealth in declaring, as it does hereby declare, that the acts aforesaid are unconstitutional, and that the necessary and proper measures will be taken by each for cooperating with this state in maintaining unimpaired the authorities, rights, and liberties, reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.3

That the governor be desired to transmit a copy of the foregoing resolutions to the executive authority of each of the other states, with a request, that the same may be communicated to the legislature thereof.

And that a copy be furnished to each of the senators and representatives representing this state in the Congress of the United States.

- 1. The First Amendment

- 2. Madison quoted from a report of the Virginia Ratifying Convention, which proposed amendments to the Constitution. See Jonathan Eliot, ed., The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution as Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia in 1787. . . , 5 vols., 2d ed., 1888, 3:657–661.

- 3. A reference to the Tenth Amendment. See Document 8.

Response to the Virginia Resolutions

February 13, 1799

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)