Introduction

George Washington wrote to Madison expressing his wish that “the Convention may adopt no temporizing expedient, but probe the defects of the Constitution to the bottom, and provide radical cures, whether they are agreed to or not.” Madison’s “Vices” is, in effect, the first draft of his famous defense of the extended republic in Federalist 10. Madison criticized the Articles because they lacked “the great vital principles of a Political Constitution,” namely, “sanction,” and “coercion.” The “evil” that alarmed him the most was that individual rights were being violated by unjust majorities in the state legislatures. Madison shifted the ground of the conversation over rights away from securing the rights of the people against the unrestrained conduct of monarchs and aristocrats to the then unfamiliar ground of securing the rights of minorities from omnipotent majorities. In the process, he questioned the efficacy of such traditional republican solutions as “a prudent regard” for the common good, “respect for character,” and the restraints provided by religion. Madison’s argument was that rights would not be secure until the constitutional protection the Articles gave to the state legislatures against federal intervention were removed. Madison felt the federal government needed this power to check factious or unjust laws. “A modification of the Sovereignty” was needed. The solution, said Madison, was to create an extended republic in which a multiplicity of opinions, passions, and interests “check each other.”

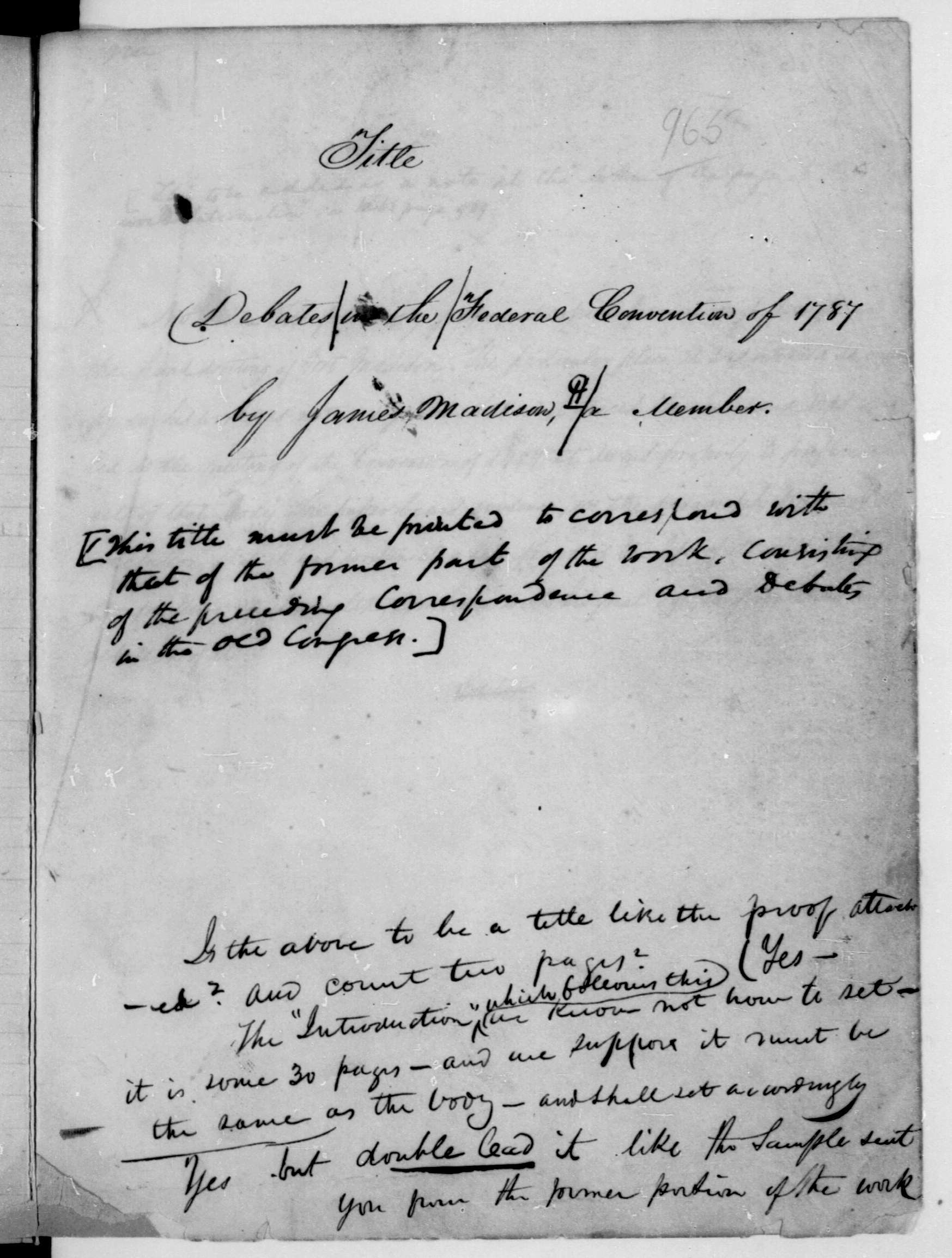

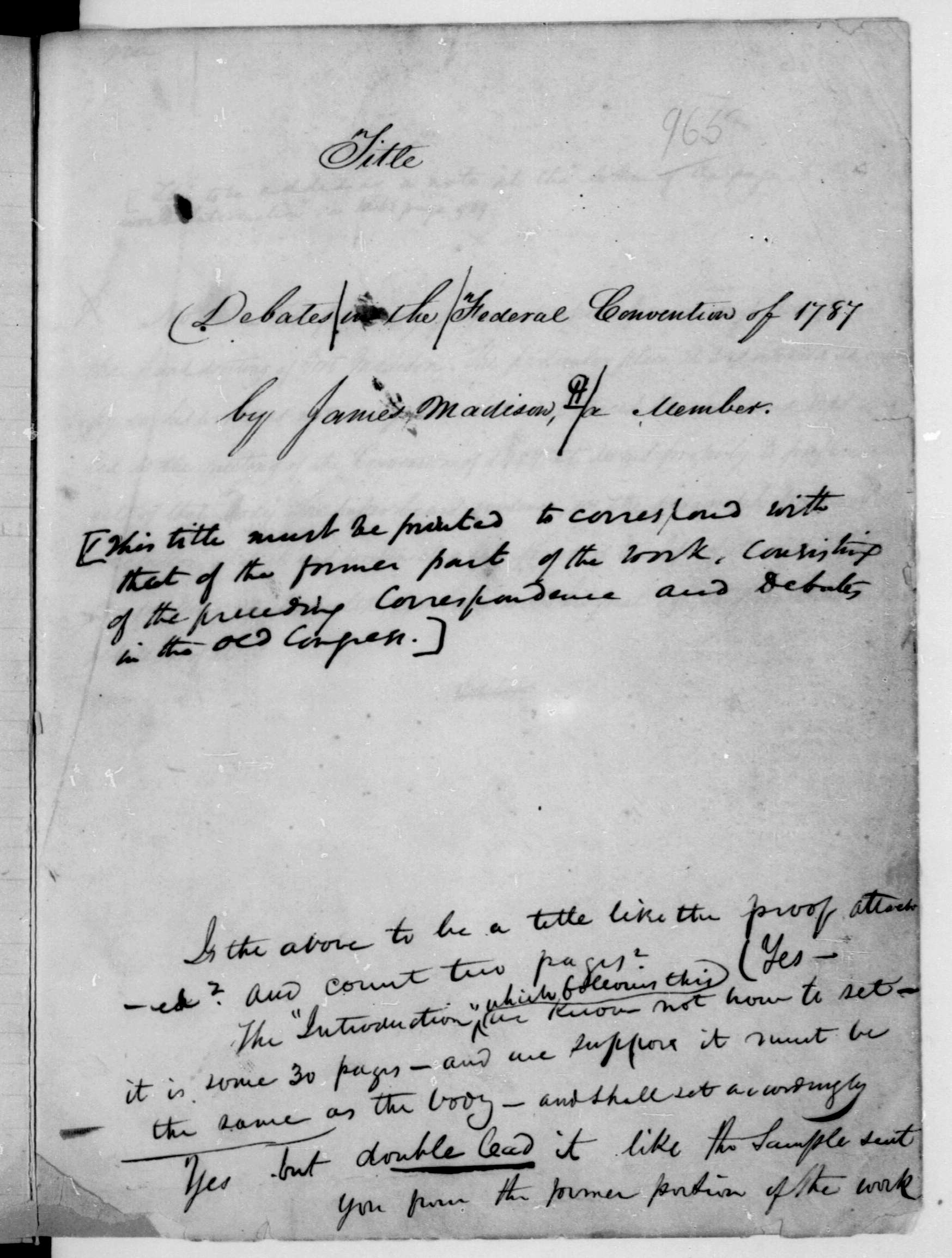

For the complete original version, including the location of Madison’s headings and inserts, see Hunt Gaillard, ed., The Writings of James Madison (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1900-1910, I: 319-328). We have followed Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner, eds., The Founders’ Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 1:166-169, and placed Madison’s section headings in the main body of the text rather than in the margin. We have, however, put the headings in upper case in order to distinguish them clearly from Madison’s commentary.

Hunt Gaillard, ed., The Writings of James Madison (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1900-1910) I: 361-369. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/g11i.

1.FAILURE OF THE STATES TO COMPLY WITH THE CONSTITUTIONAL REQUISITIONS.1

This evil has been so fully experienced both during the war and since the peace, results so naturally from the number and independent authority of the States, and has been so uniformly exemplified in every similar Confederacy, that it may be considered as not less radically and permanently inherent in, than it is fatal to the object of, the present System.

2.ENCROACHMENTS BY THE STATES ON THE FEDERAL AUTHORITY.

Examples of this are numerous and repetitions may be foreseen in almost every case where any favorite object of a State shall present a temptation. Among these examples are the wars and Treaties of Georgia with the Indians, the unlicensed compacts between Virginia and Maryland, and between Pennsylvania and New Jersey, the troops raised and to be kept up by Massachusetts.

3.VIOLATIONS OF THE LAW OF NATIONS AND OF TREATIES.

From the number of Legislatures, the sphere of life from which most of their members are taken, and the circumstances under which their legislative business is carried on, irregularities of this kind must frequently happen. Accordingly, not a year has passed without instances of them in some one or other of the States. The Treaty of peace, the treaty with France, the treaty with Holland, have each been violated.2 The causes of these irregularities must necessarily produce frequent violations of the law of nations in other respects.

As yet foreign powers have not been rigorous in animadverting3 on us. This moderation, however, cannot be mistaken for a permanent partiality to our faults, or a permanent security against those disputes with other nations, which, being among the greatest of public calamities, it ought to be least in the power of any part of the community to bring on the whole.

4.TRESPASSES OF THE STATES ON THE RIGHTS OF EACH OTHER.

These are alarming symptoms, and may be daily apprehended, as we are admonished by daily experience. See the law of Virginia restricting foreign vessels to certain ports; of Maryland in favor of vessels belonging to her own citizens; of New York in favor of the same.

Paper money, instalments of debts, occlusion of courts,4 making property a legal tender, may likewise be deemed aggressions on the rights of other States. As the citizens of every State, aggregately taken, stand more or less in the relation of creditors or debtors to the citizens of every other State, acts of the debtor State in favor of debtors affect the creditor State in the same manner, as they do its own citizens, who are, relatively, creditors towards other citizens. This remark may be extended to foreign nations. If the exclusive regulation of the value and alloy of coin was properly delegated to the federal authority, the policy of it equally requires a control on the States in the cases above mentioned. It must have been meant — 1. To preserve uniformity in the circulating medium throughout the nation. 2. To prevent those frauds on the citizens of other States, and the subjects of foreign powers, which might disturb the tranquility at home, or involve the Union in foreign contests.

The practice of many States in restricting the commercial intercourse with other States, and putting their productions and manufactures on the same footing with those of foreign nations, though not contrary to the federal articles, is certainly adverse to the spirit of the Union, and tends to beget retaliating regulations, not less expensive and vexatious in themselves than they are destructive of the general harmony.

5.WANT OF CONCERT IN MATTERS WHERE COMMON INTEREST REQUIRES IT.

This defect is strongly illustrated in the state of our commercial affairs. How much has the national dignity, interest, and revenue, suffered from this cause? Instances of inferior moments are the want of uniformity in the laws concerning naturalization and literary property; of provision for national seminaries;5 for grants of incorporation for national purposes, for canals and other works of general utility; which may at present be defeated by the perverseness of particular States whose concurrence is necessary.

6.WANT OF GUARANTY TO THE STATES OF THEIR CONSTITUTIONS AND LAWS AGAINST INTERNAL VIOLENCE.

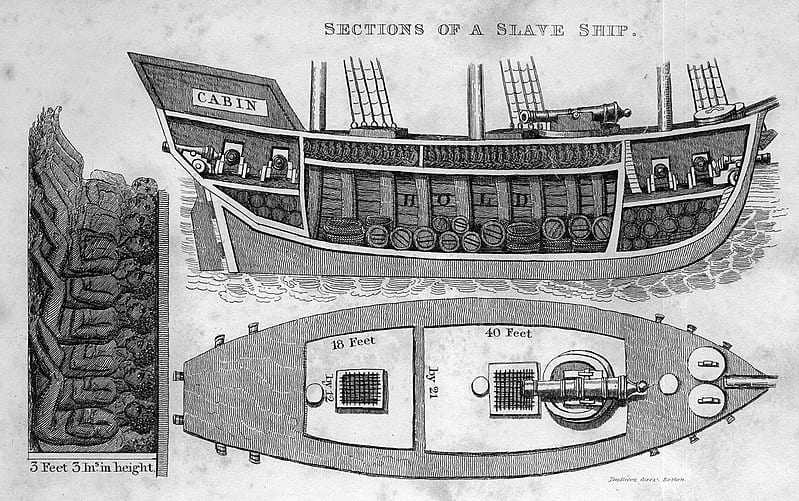

The Confederation is silent on this point, and therefore by the second article the hands of the federal authority are tied. According to Republican Theory, Right and power being both vested in the majority, are held to be synonymous. According to fact and experience, a minority may, in an appeal to force, be an overmatch for the majority. 1. If the minority happen to include all such as possess the skill and habits of military life, and such as possess the great pecuniary resources, one third only may conquer the remaining two thirds. 2. One third of those who participate in the choice of the rulers, may be rendered a majority by the accession6 of those whose poverty excludes them from a right of suffrage, and who for obvious reasons will be more likely to join the standard of sedition than that of the established Government. 3. Where slavery exists, the republican Theory becomes still more fallacious.

7.WANT OF SANCTION TO THE LAWS, AND OF COERCION IN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE CONFEDERACY.

A sanction is essential to the idea of law, as coercion is to that of Government. The federal system being destitute of both, wants the great vital principles of a Political Constitution. Under the form of such a Constitution, it is in fact nothing more than a treaty of amity, of commerce, and of alliance, between independent and Sovereign States. From what cause could so fatal an omission have happened in the articles of Confederation? From a mistaken confidence that the justice, the good faith, the honor, the sound policy of the several legislative assemblies would render superfluous any appeal to the ordinary motives by which the laws secure the obedience of individuals; a confidence which does honor to the enthusiastic virtue of the compilers, as much as the inexperience of the crisis apologizes for their errors. The time which has since elapsed has had the double effect of increasing the light and tempering the warmth with which the arduous work may be revised. It is no longer doubted that a unanimous and punctual obedience of 13 independent bodies to the acts of the federal Government ought not to be calculated on. Even during the war, when external danger supplied in some degree the defect of legal and coercive sanctions, how imperfectly did the States fulfill their obligations to the Union? In time of peace we see already what is to be expected. How, indeed, could it be otherwise? In the first place, every general act of the Union must necessarily bear unequally hard on some particular member or members of it; secondly, the partiality of the members to their own interests and rights, a partiality which will be fostered by the courtiers of popularity, will naturally exaggerate the inequality where it exists, and even suspect it where it has no existence; thirdly, a distrust of the voluntary compliance of each other may prevent the compliance of any, although it should be the latent disposition of all. Here are causes and pretexts which will never fail to render federal measures abortive. If the laws of the States were merely recommendatory to their citizens, or if they were to be rejudged by county authorities, what security, what probability would exist that they would be carried into execution? Is the security or probability greater in favor of the acts of Congress, which, depending for their execution on the will of the State legislatures, which are tho’ nominally authoritative, in fact recommendatory only?

8.WANT OF RATIFICATION BY THE PEOPLE OF THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION.

In some of the States the Confederation is recognized by and forms a part of the Constitution. In others, however, it has received no other sanction than that of the Legislative authority. From this defect two evils result: 1. Whenever a law of a State happens to be repugnant to an act of Congress, particularly when the latter is of posterior date to the former, it will be at least questionable whether the latter must not prevail; and as the question must be decided by the Tribunals of the State, they will be most likely to lean on the side of the State. 2. As far as the Union of the States is to be regarded as a league of sovereign powers, and not as a political Constitution, by virtue of which they are become one sovereign power, so far it seems to follow from the doctrine of compacts, that a breach of any of the articles of the confederation by any of the parties to it absolves the other parties from their respective obligations, and gives them a right if they choose to exert it, of dissolving the Union altogether.

9.MULTIPLICITY OF LAWS IN THE SEVERAL STATES.

In developing the evils which viciate the political system of the United States, it is proper to include those which are found within the States individually, as well as those which directly affect the States collectively, since the former class have an indirect influence on the general malady, and must not be overlooked in forming a complete remedy. Among the evils, then, of our situation, may well be ranked the multiplicity of laws, from which no State is exempt. As far as laws are necessary to mark with precision the duties of those who are to obey them, and to take from those who are to administer them a discretion which might be abused, their number is the price of liberty. As far as the laws exceed this limit they are a nuisance; a nuisance of the most pestilent kind. Try the Codes of the several States by this test, and what a luxuriancy7 of legislation do they present. The short period of independency has filled as many pages as the century which preceded it. Every year, almost every session, adds a new volume. This may be the effect in part, but it can only be in part, of the situation in which the revolution has placed us. A review of the several Codes will show that every necessary and useful part of the least voluminous of them might be compressed into one tenth of the compass, and at the same time be rendered tenfold as perspicuous.8

10.MUTABILITY OF THE LAWS OF THE STATES.

This evil is intimately connected with the former, yet deserves a distinct notice, as it emphatically denotes a vicious legislation. We daily see laws repealed or superseded before any trial can have been made of their merit, and even before a knowledge of them can have reached the remoter districts within which they were to operate. In the regulations of trade this instability becomes a snare not only to our citizens but to foreigners also.

11.INJUSTICE OF THE LAWS OF STATES.

If the multiplicity and mutability of laws prove a want of wisdom, their injustice betrays a defect still more alarming; more alarming, not merely because it is a greater evil in itself, but because it brings more into question the fundamental principle of republican Government, that the majority who rule in such Governments are the safest guardians both of public good and of private rights. To what causes is this evil to be ascribed?

These causes lie —1. in the Representative bodies. 2. in the people themselves.

- Representative appointments are sought from 3 motives: (1) Ambition (2) Personal interest. (3) Public good.

Unhappily, the two first are proved by experience to be most prevalent. Hence, the candidates who feel them, particularly, the second, are most industrious, and most successful in pursuing their object; and forming often a majority in the legislative Councils, with interested views, contrary to the interest and views of their constituents, join in a perfidious sacrifice of the latter to the former. A succeeding election, it might be supposed, would displace the offenders, and repair the mischief. But how easily are base and selfish measures masked by pretexts of public good and apparent expediency? How frequently will a repetition of the same arts and industry which succeeded in the first instance again prevail on the unwary to misplace their confidence?

How frequently, too, will the honest but unenlightened representative be the dupe of a favorite leader, veiling his selfish views under the professions of public good, and varnishing his sophistical arguments with the glowing colors of popular eloquence?

- A still more fatal, if not more frequent cause, lies among the people themselves. All civilized societies are divided into different interests and factions, as they happen to be creditors or debtors, rich or poor, husbandmen, merchants, or manufacturers, members of different religious sects, followers of different political leaders, inhabitants of different districts, owners of different kinds of property and &c, &c. In republican Government, the majority, however composed, ultimately give the law. Whenever, therefore, an apparent interest or common passion unites a majority, what is to restrain them from unjust violations of the rights and interests of the minority, or of individuals? Three motives only: 1. A prudent regard to their own good, as involved in the general and permanent good of the community. This consideration, although of decisive weight in itself, is found by experience to be too often unheeded. It is too often forgotten, by nations as well as by individuals, that honesty is the best policy. 2dly. Respect for character. However strong this motive may be in individuals, it is considered as very insufficient to restrain them from injustice. In a multitude its efficacy is diminished in proportion to the number which is to share the praise or the blame. Besides, as it has reference to public opinion, which within a particular society, is the opinion of the majority, the standard is fixed by those whose conduct is to be measured by it. The public opinion without the society will be little respected by the people at large of any Country. Individuals of extended views and of national pride may bring the public proceedings to this standard, but the example will never be followed by the multitude. Is it to be imagined that an ordinary citizen or even an Assemblyman of R[hode] Island, in estimating the policy of paper money, ever considered or cared in what light the measure would be viewed in France or Holland; or even in Massachusetts or Connecticut? It was a sufficient temptation to both that it was for their interest; it was a sufficient sanction to the latter that it was popular in the State; to the former that it was so in the neighborhood. 3dly. Will Religion, the only remaining motive be a sufficient restraint? It is not pretended to be such, on men individually considered. Will its effect be greater on them considered in an aggregate view? Quite the reverse. The conduct of every popular assembly acting on oath, the strongest of religious ties, proves that individuals join without remorse in acts against which their consciences would revolt if proposed to them under the like sanction, separately, in their closets. When, indeed, Religion is kindled into enthusiasm, its force, like that of other passions, is increased by the sympathy of a multitude. But enthusiasm is only a temporary state of religion, and, while it lasts, will hardly be seen with pleasure at the helm of Government. Besides, as religion in its coolest state, is not infallible, it may become a motive to oppression as well as a restraint from injustice. Place three individuals in a situation wherein the interest of each depends on the voice of the others, and give to two of them an interest opposed to the rights of the third: Will the latter be secure? The prudence of every man would shun the danger. The rules and forms of justice suppose and guard against it. Will two thousand in a like situation be less likely to encroach on the rights of one thousand? The contrary is witnessed by the notorious factions and oppressions which take place in corporate towns, limited as the opportunities are, and in little republics, when uncontrolled by apprehensions of external danger. If an enlargement of the sphere is found to lessen the insecurity of private rights, it is not because the impulse of a common interest or passion is less predominant in this case with the majority; but because a common interest or passion is less apt to be felt, and the requisite combinations less easy to be formed, by a great than by a small number. The society becomes broken into a greater variety of interests and pursuits of passions, which check each other, whilst those who may feel a common sentiment have less opportunity of communication and concert. It may be inferred that the inconveniences of popular States contrary to the prevailing Theory, are in proportion not to the extent, but to the narrowness of their limits.

The great desideratum9 in Government is such a modification of the sovereignty as will render it sufficiently neutral between the different interests and factions to control one part of the Society from invading the rights of another, and, at the same time, sufficiently controlled itself from setting up an interest adverse to that of the whole society. In absolute Monarchies the prince is sufficiently neutral towards his subjects, but frequently sacrifices their happiness to his ambition or his avarice. In small Republics, the sovereign will is sufficiently controlled from such a Sacrifice of the entire Society, but is not sufficiently neutral towards the parts composing it. As a limited monarchy tempers the evils of an absolute one, so an extensive Republic meliorates the administration of a small Republic.

An auxiliary desideratum for the melioration of the Republican form is such a process of elections as will most certainly extract from the mass of the society the purest and noblest characters which it contains; such as will at once feel most strongly the proper motives to pursue the end of their appointment, and be most capable to devise the proper means of attaining it.

- 1. Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress requested money from the states, which often failed to meet their obligations for the reasons Madison gives in his essay.

- 2. Madison refers, apparently, to the Treaty of Paris (1783) that ended the Revolutionary War, the Treaty of Alliance (1778) between the United States and France, and the Treaty of Amity and Commerce (1782) with the Dutch Republic.

- 3. taking notice of this and censuring us for it

- 4. closing courts to prevent legal proceedings to recover debts

- 5. schools

- 6. consent

- 7. overgrowth

- 8. easily understood

- 9. thing that is desired

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)