“Let Cicero then live in submission and servitude, since he is capable of it; and neither his age nor his honors nor his past actions, make him ashamed to suffer it. For my own part, no condition of slavery, how honorable soever it may appear, shall hinder me from declaring war against tyranny, against decrees irregularly made, against unjust domination, and every power that would set itself above the laws.”

-Brutus.

The dangers of adopting the new Constitution having been pointed out, I shall now proceed to consider, whether it would be necessary and proper, and, whether Americans have any good reason to put more confidence in their rulers than Europeans.

It is admitted that it has been matter of dispute at all times, whether a monarchical, aristocratic or democratic government is the best. It was the case in the time of Samuel, and in the council of the seven provinces of Persia. This was also the case with the Dutch upon their revolt from Philip the second, with the English after the death of Charles the first, and the Americans during the late revolution.

It is, however, established by the experience of all ages that in the two first, there is no security for the rights of the people, in the last, no dispatch. “That the two first are too strong, encroach too much upon liberty, and incline too much to tyranny; the last too weak, delivers people too much to themselves, and tends to confusion and licentiousness.”

These were the rocks we had to avoid when, in 1777, we agreed to a republican government.

“In political arithmetic, it is necessary to substitute a calculation of probabilities to mathematical exactness. That force which continually impels us to our own private interests, like gravity, acts incessantly, unless it meets an obstacle to oppose it.”

“A perfect government (says Rollin) would be that which should unite in itself, all the advantages of the three former, and avoid the dangers and inconveniences they include,” and then it is called a republican or mixed government. Such, even in their present state, are the English and the Dutch.

But difficulty remained: what proportion of ingredients should be taken out of each; or, in the words of Montesquieu, “to combine the several powers, to regulate, temper and set them in motion to give as it were ballast to the one, in order to enable it to resist the other.” (The English and the Dutch have missed it in their compound, by adopting, the first, too great a proportion of the monarchical, the Dutch, too much of the aristocratic ingredient.). Even then, all the difficulties would not be removed as the fundamental principles they act upon are so different.

In a monarchy, the king* rules in duplicity and partiality, and makes himself respectable among the nations of the earth, by luxury, extravagance** and dissipation; when, on the contrary, in a republic there is no king except the LORD OF HOSTS, the pillars of whose government are righteousness*** and truth; and to them and them only, ought all nations upon earth to look for respectability. In considering the rules of propriety, the principal object with the one is, how to be generous, the other how to be just. And in respect to the public burdens, the former considers how much he can spend, the latter, how much they can save; that, how much the people can bear, this how little may do. The Congress at Philadelphia (a body of men, in the words of Mr. Pitt, “that for solidity of reasoning, force of sagacity, and wisdom of conclusion, no nation or body of men stand in preference to”), upon the greatest deliberation and circumspection, unanimously agreed to a republican from; wherein, they have united all the advantages of the three former, and, as much as possible, avoided the dangers and inconveniences of each (the objection of Maryland was not to the form of the government, but to the soil and jurisdiction of all the western lands, not foreseeing, as they now do or soon will, the dangerous tendency it would have to the liberty and property of the old states) not that I suppose it perfect. For I hold, that there never was nor ever will be a government perfect, so as not to be open to corruption (unless at Millennium) but I am persuaded, that every person who has considered the difference between the condition of the people in Europe, compared with those of the United States of America, will agree with Doctor Franklin, who says, “whoever has traveled through the various parts of Europe, and observed how small is the proportion of people in affluence or easy circumstances there, compared to those in poverty and misery, the few haughty landlords, with the multitude of poor, abject, rack-renter, to the paying tenants and half paid, and half-starved ragged laborers, and views here the happy mediocrity, that so generally prevails throughout these states, where the cultivator works for himself, and supports his family with decent plenty, will see abundant reason to bless Providence for the evidence and great difference in our favor, and be convinced that nation known to us enjoys a greater share of human felicity.”

The good opinion I have of the frame and composition as well of the Confederation as the several states Constitutions; and that they are if administered up on republican principles, the greatest principles, the greatest blessing we enjoy; the danger I apprehend of the one proposed, that it will become the greatest curse and be the means of destroying ours, as the like measures ever have destroyed the liberties of every people that have attempted to do so, has led me into the following discussions, conceiving it not only the duty of a patriot to inquire, like Daniel, Whose footsteps are these? but to call out like Paul, Stand fast in the liberty, be not entangled with the yoke of bondages. “What, in a quarrel (says Vattel) that is going to decide forever their most valuable interests and their very safety, are the people to stand by as tranquil spectators, as a flock of sheep is, to wait till it be determined whether they are to be delivered to the butcher or restored to the shepherd’s care.”

For my own part, I adopt the sentiments of Sidney, “While I live I shall endeavor to preserve my liberty, or at least not consent to the destroying of it. I hope I shall die in the same principle in which I lived, and will no longer live than they can preserve me.”

In my discussions on this subject, I do not mean to ascribe every bad consequence that may appear to flow necessarily from certain measures to the evil intentions of ALL those that advocate the measure, not to every member of Congress; for I am well assured, that there have been at all times members in that honorable body, and even among the wealthy, that have disapproved of the measure and acted the worthy patriots, and others, that deserve no more blame than those who in their innocence accompanied Absalom in his treasonable practices, it being even a hard fate that the burden of the proof was turned upon them, without an evil intent. And as it will require to point out the reprehensible conduct of the public officers, which will sometimes also apply to their superiors, I shall endeavor to do it with as much delicacy as I am able, consistent with truth; and “truth (says Montague) will never offend the honest and well meaning, for the plain dealing remonstrances of a friend differ as widely from the rancor of an enemy, as the friendly probe of a physician from the dagger of an assassin.” Yet, in sentiment with Hardwick, “that there is a decency required in tracing the faults of past times, we may look for information and warning, and even reproof, but not invective.”

*”Kings hate virtuous men who oppose their unjust designs, but caress the wicked who favor them.” 2 Bulamaqui 67. Montague 276.

“In monarchies, the actions of men are judged not as virtuous but as shining–nots as just but as great–not as reasonable but as extraordinary.” 1 Montesquieu 36.

“In monarchies, policy effects great things by as little virtue as possible, if there should chance be some unlucky, honest man, Cardinal Richelieu, in his political testament, seems to hint, that a prince should take care not to employ him: so true it is that virtue is not the mainspring of this Government.” 3 Montesquieu 28, 30.

**”Luxury is absolutely necessary in monarchies; hence arises a very natural reflection. Republics end with luxury, monarchy with poverty.” Ibid. 124.

***”There is no great share of probity necessary to the support of monarchical or despotic government; but in a popular state one spring more is necessary, namely virtue. When virtue is banished, ambition invades the hearts of those that are disposed to receive it, and avarice possesses the whole community.” 1 Montesquieu, 24, 25.

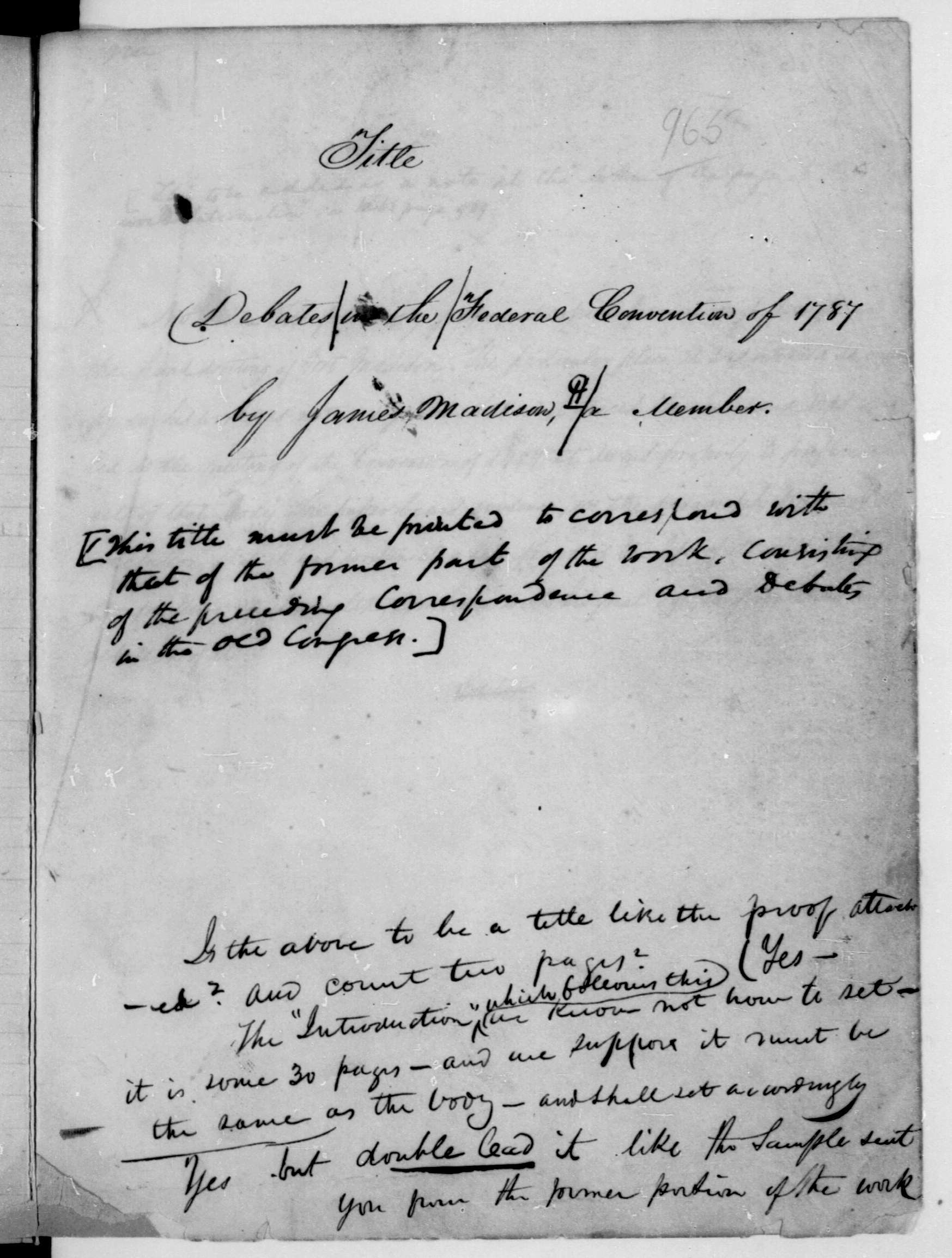

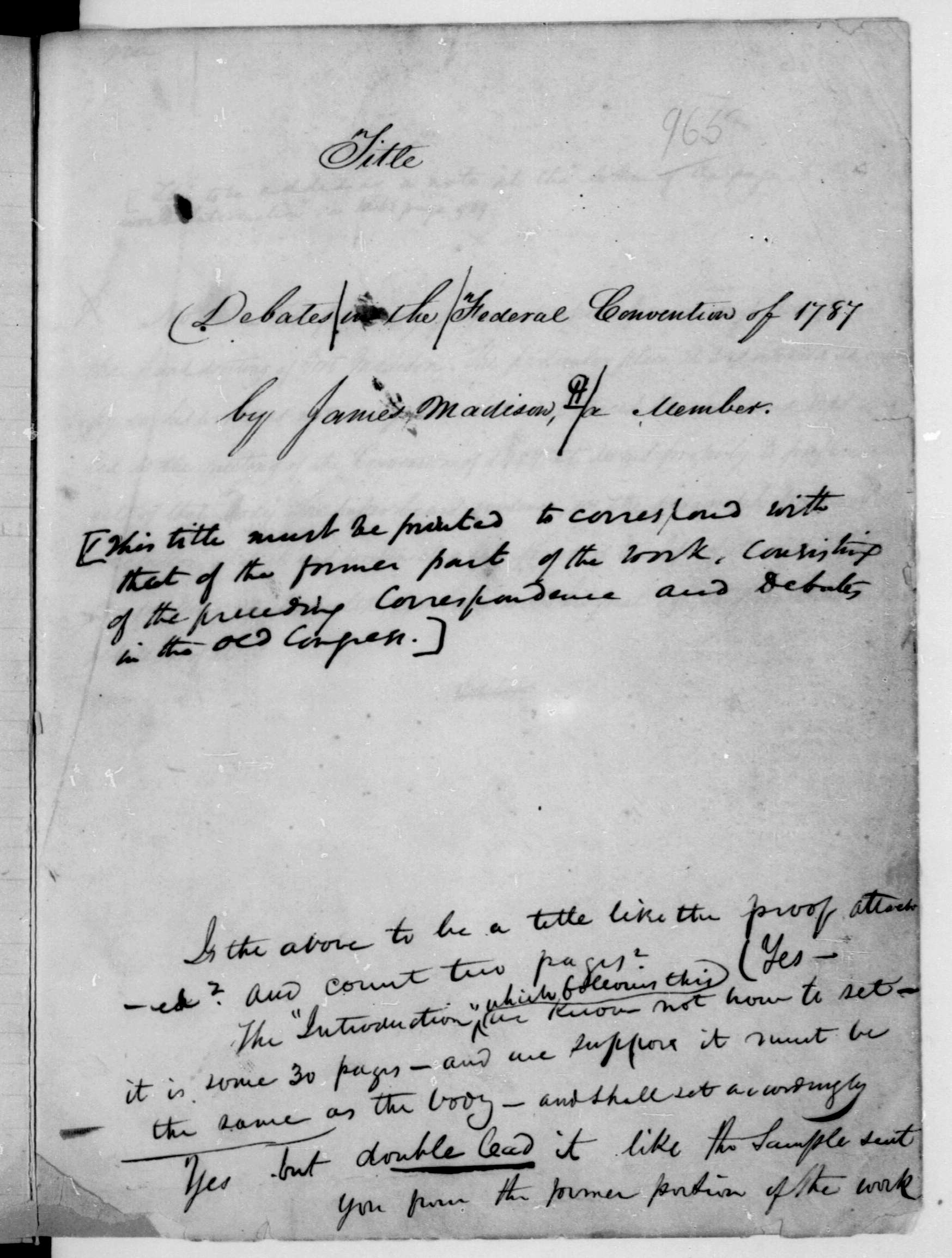

Federalist 59

February 22, 1788

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)