Introduction

In the Virginia Plan, the powers of Congress seem to be unlimited, certainly when compared to the specific enumeration of powers in the Articles of Confederation. The New Jersey Plan reflected the hesitation of numerous delegates to give Congress the power to do what the states were deemed, by Congress, incapable of doing. The first time the powers of Congress are listed is in the Committee of Detail Report of August 6. Although the necessary and proper clause first appears in the Committee of Detail, September 14 marks the first time that a serious discussion takes place over the meaning of this clause.

From September 12 to September 17, the delegates debated the Committee of Style Report that refined the Committee of Detail listing of 18 powers of Congress. The “necessary and proper” clause received the most attention. The exchange on September 14 leaves us pondering what is included and what is excluded in the clause. For example, James Madison and Charles Pinckney moved to insert in the list of powers one to “establish an University, in which no preferences or distinctions should be allowed on account of religion” Gouverneur Morris mentioned that it was not necessary to be that specific. On the question, it was defeated 6–4–1. That is a division over whether a strict or a loose interpretation of the power of Congress is necessary and proper.

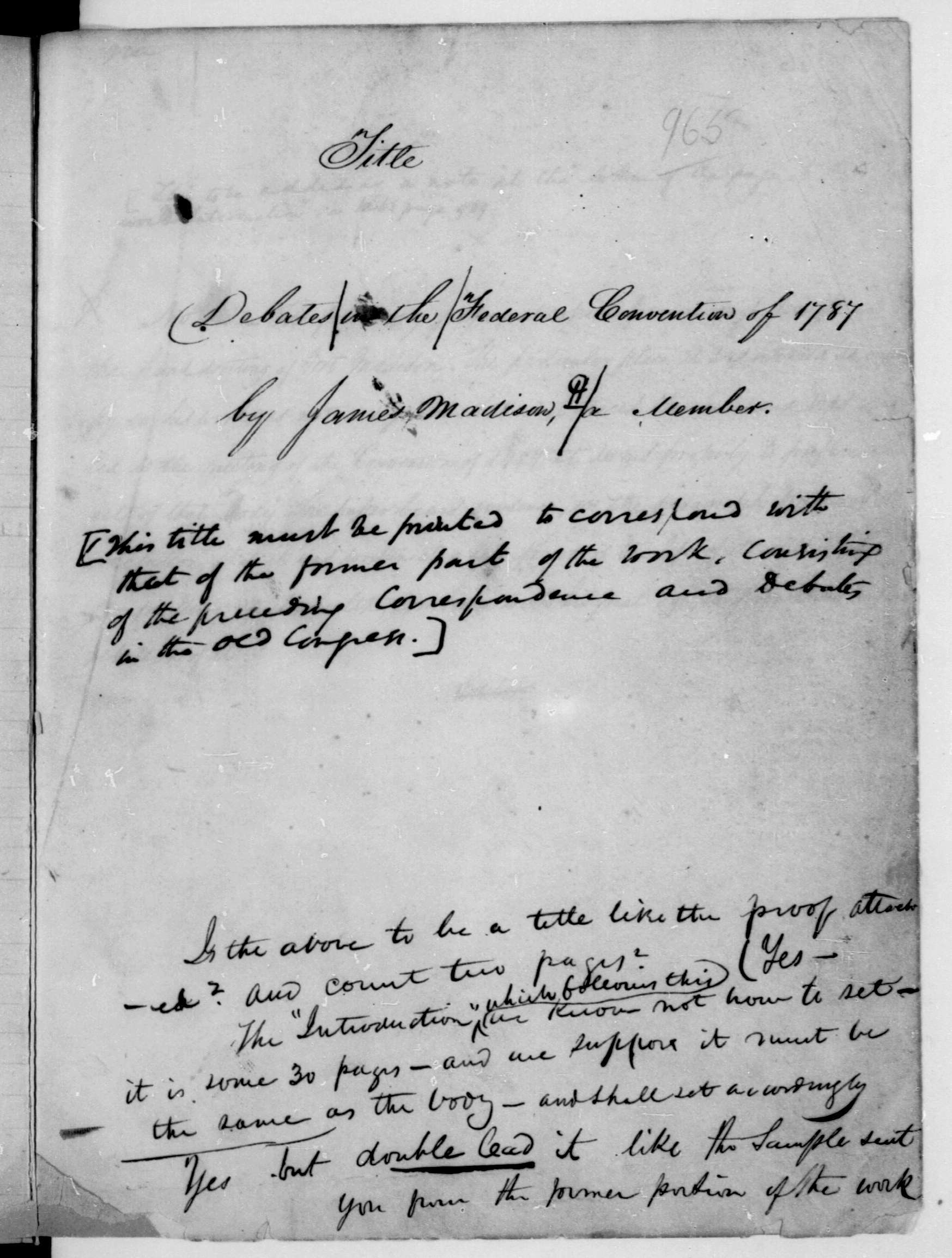

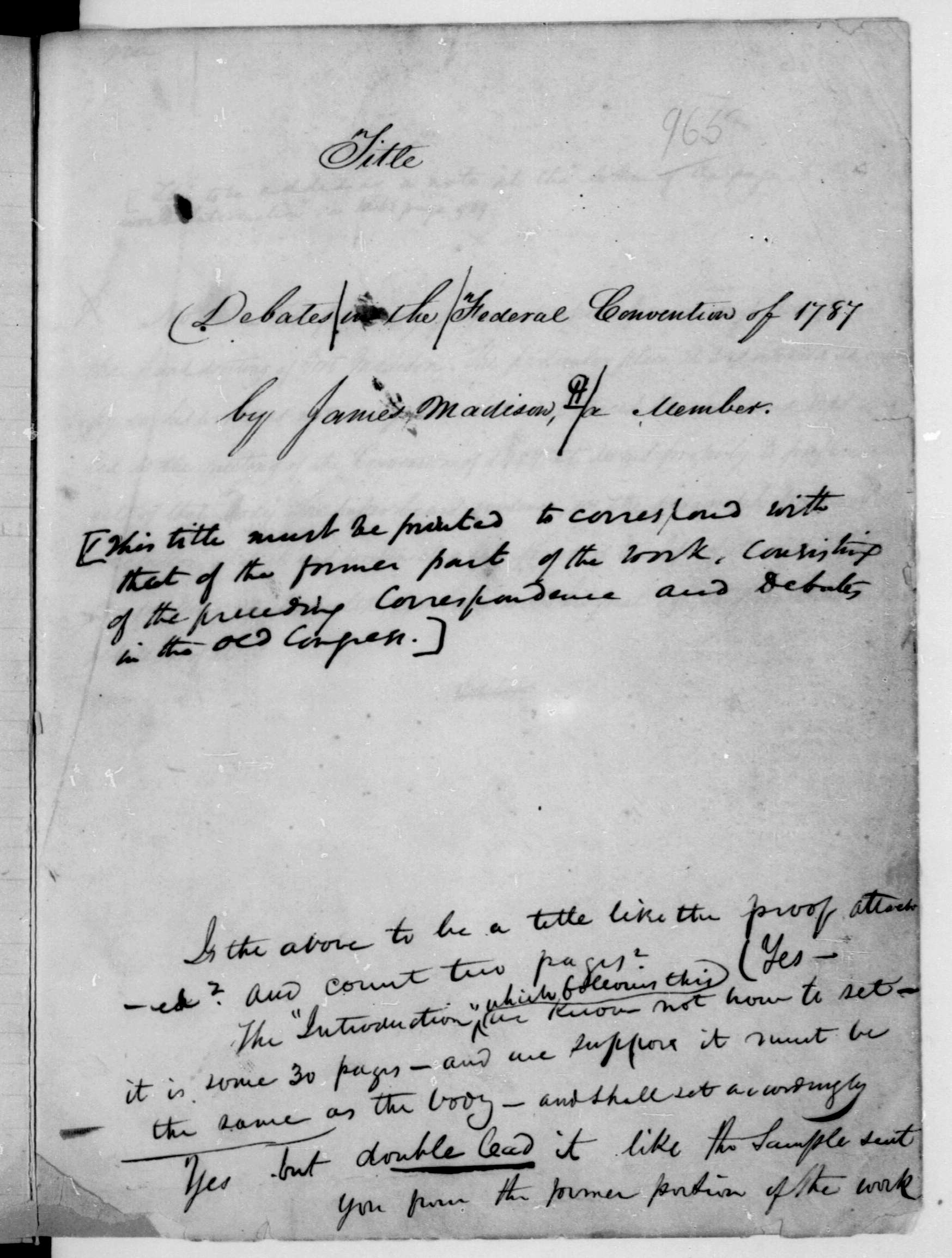

Source: Gordon Lloyd, ed., Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 by James Madison, a Member (Ashland, OH: Ashbrook Center, 2014), 512–27, 530–37.

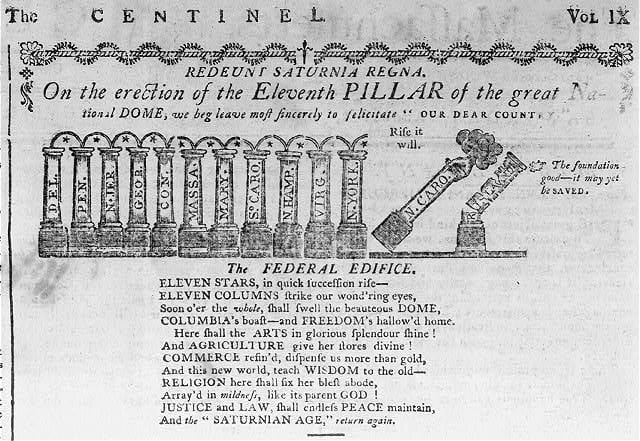

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE OF STYLE | September 12, 1787

[Preamble]

We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, to establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America:

Article I

. . . Sect. 8. The Congress may by joint ballot appoint a Treasurer. They shall have power, –

To lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.

To borrow money on the credit of the United States.

To regulate commerce with foreign nations, among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.

To establish an uniform rule of naturalization, and uniform laws on the subject of bankruptcies throughout the United States.

To coin money, regulate the value thereof, and of foreign coin, and fix the standard of weights and measures.

To provide for the punishment of counterfeiting the securities and current coin of the United States.

To establish post offices and post roads.

To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.

To constitute tribunals inferior to the Supreme Court.

To define and punish piracies and felonies committed on the high seas, and [punish] offences against the law of nations.

To declare war, grant letters of marque and reprisal, and make rules concerning captures on land and water.

To raise and support armies: but no appropriations of money to that use shall be for a longer term than two years.

To provide and maintain a navy.

To make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces.

To provide for calling forth the militia, to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions.

To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the militia, and for governing such part of them as may be employed in the service of the United States; reserving to the States, respectively, the appointment of the officers, and the authority of training the militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress.

To exercise exclusive legislation, in all cases whatsoever, over such district (not exceeding ten miles square) as may, by cession of particular States, and the acceptance of Congress, become the seat of government of the United States; and to exercise like authority over all places purchased by the consent of the Legislature of the State in which the same shall be, for the erection of forts, magazines, arsenals, dock-yards, and other needful buildings. And,

To make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any department or officer thereof. . . .

Friday, September 14

In Convention. – The Report of the Committee of Style and Arrangement being resumed, –

. . . Article 1, Sect. 8. The Congress “may by joint ballot appointed a Treasurer,” –

Mr. RUTLEDGE[1] moved to strike out this power, and let the Treasurer be appointed in the same manner with other officers.

Mr. GORHAM[2] and Mr. KING[3] said that the motion, if agreed to, would have a mischievous tendency. The people are accustomed and attached to that mode of appointing Treasurers, and the innovation will multiply objections to the system.

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS[4] remarked, that if the Treasurer be not appointed by the Legislature, he will be more narrowly watched, and more readily impeached.

Mr. SHERMAN.[5] As the two Houses appropriate money, it is best for them to appoint the officer who is to keep it; and to appoint him as they make the appropriation, not by joint, but several votes.

General PINCKNEY.[6] The Treasurer is appointed by joint ballot in South Carolina. The consequence is, that bad appointments are made, and the Legislature will not listen to the faults of their own officer.

On the motion to strike out, –

New Hampshire, Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, aye, – 8; Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, no, – 3.

Article 1, Sect. 8, – the words “but all such duties, imposts, and excises, shall be uniform throughout the United States,” were unanimously annexed to the power of taxation.

On the clause, “to define and punish piracies and felonies on the high seas, and punish offences against the law of nations,” –

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS moved to strike out “punish,” before the words, “offences against the law of nations,” so as to let these be definable, as well as punishable, by virtue of the preceding member of the sentence.

Mr. WILSON[7] hoped the alteration would by no means be made. To pretend to define the law of nations, which depended on the authority of all the civilized nations of the world, would have a look of arrogance that would make us ridiculous.

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS. The word define is proper when applied to offences in this case; the law of nations being often too vague and deficient to be a rule.

On the question to strike out the word “punish,” it passed in the affirmative, –

New Hampshire, Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, North Carolina, South Carolina, aye, – 6; Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, Georgia, no, – 5.

Doctor FRANKLIN[8] moved to add, after the words, “post roads,” Article 1, Sect. 8, a power “to provide for cutting canals where deemed necessary.”

Mr. WILSON seconded the motion.

Mr. SHERMAN objected. The expense in such cases will fall on the United States, and the benefit accrue to the places where the canals may be cut.

Mr. WILSON. Instead of being an expense to the United States, they may be made a source of revenue.

Mr. MADISON[9] suggested an enlargement of the motion, into a power “to grant charters of incorporation where the interest of the United States might require, and the legislative provisions of individual States may be incompetent.” His primary object was, however, to secure an easy communication between the States, which the free intercourse now to be opened seemed to call for. The political obstacles being removed, a removal of the natural ones, as far as possible ought to follow.

Mr. RANDOLPH[10] seconded the proposition.

Mr. KING thought the power unnecessary.

Mr. WILSON. It is necessary to prevent a State from obstructing the general welfare.

Mr. KING. The States will be prejudiced and divided into parties by it. In Philadelphia and New York, it will be referred to the establishment of a bank, which has been a subject of contention in those cities. In other places it will be referred to mercantile monopolies.

Mr. WILSON mentioned the importance of facilitating, by canals the communication with the Western settlements. As to banks, he did not think with Mr. KING, that the power in that point of view would excite the prejudices and parties apprehended. As to mercantile monopolies, they are already included in the power to regulate trade.

Colonel MASON[11] was for limiting the power to the single case of canals. He was afraid of monopolies of every sort, which he did not think were by any means already implied by the Constitution, as supposed by Mr. WILSON.

The motion being so modified as to admit a distinct question specifying and limited to the case of canals, –

Pennsylvania, Virginia, Georgia, aye, – 3; New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, no, – 8.

The other part fell, of course, as including the power rejected.

Mr. MADISON and Mr. PINCKNEY[12] then moved to insert, in the list of powers vested in Congress, a power “to establish an University, in which no preferences or distinctions should be allowed on account of religion.”

Mr. WILSON supported the motion.

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS. It is not necessary. The exclusive power at the seat of government will reach the object.

On the question, – Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, aye, – 4; New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Georgia, no, – 6; Connecticut, divided, (Dr. JOHNSON,[13] aye; Mr. SHERMAN, no.)

Colonel MASON, being sensible that an absolute prohibition of standing armies in time of peace might be unsafe, and wishing at the same time to insert something pointing out and guarding against the danger of them, moved to preface the clause (Article 1, Sect. 8), “to provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the militia,” etc., with the words, “and that the liberties of the people may be better secured against the danger of standing armies in time of peace.”

Mr. RANDOLPH seconded the motion.

Mr. MADISON was in favor of it. It did not restrain Congress from establishing a military force in time of peace, if found necessary; and as armies in time of peace are allowed on all hands to be an evil, it is well to discountenance them by the Constitution, as far as will consist with the essential power of the Government on that head.

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS opposed the motion, as setting a dishonorable mark of distinction on the military class of citizens.

Mr. PINCKNEY and Mr. BEDFORD[14] concurred in the opposition.

On the question, – Virginia, Georgia, aye, – 2; New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, no, – 9.

Colonel MASON moved to strike out from the clause (Article 1, Sect. 9), “no bill of attainder, nor any ex post facto law, shall be passed,” the words “nor any ex post facto law.” He thought it not sufficiently clear, that the prohibition meant by this phrase was limited to cases of a criminal nature; and no legislature ever did or can altogether avoid them in civil cases.

Mr. GERRY[15] seconded the motion; but with a view to extend the prohibition to “civil cases,” which he thought ought to be done.

On the question, all the States were, no.

Mr. PINCKNEY and Mr. GERRY, moved to insert a declaration, “that the liberty of the press should be inviolably observed.”

Mr. SHERMAN. It is unnecessary. The power of Congress does not extend to the press.

On the question, it passed in the negative, – Massachusetts, Maryland, Virginia, South Carolina, aye, – 4; New Hampshire, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, North Carolina, Georgia, no, – 7.

- 1. John Rutledge, South Carolina

- 2. Nathaniel Gorham, Massachusetts

- 3. Rufus King, Massachusetts

- 4. Gouverneur Morris, Pennsylvania

- 5. Roger Sherman, Connecticut

- 6. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, South Carolina

- 7. James Wilson, Pennsylvania

- 8. Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania

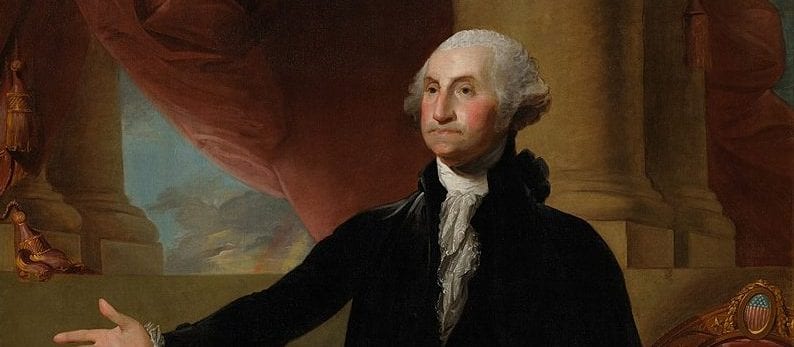

- 9. James Madison, Virginia

- 10. Edmund J. Randolph, Virginia

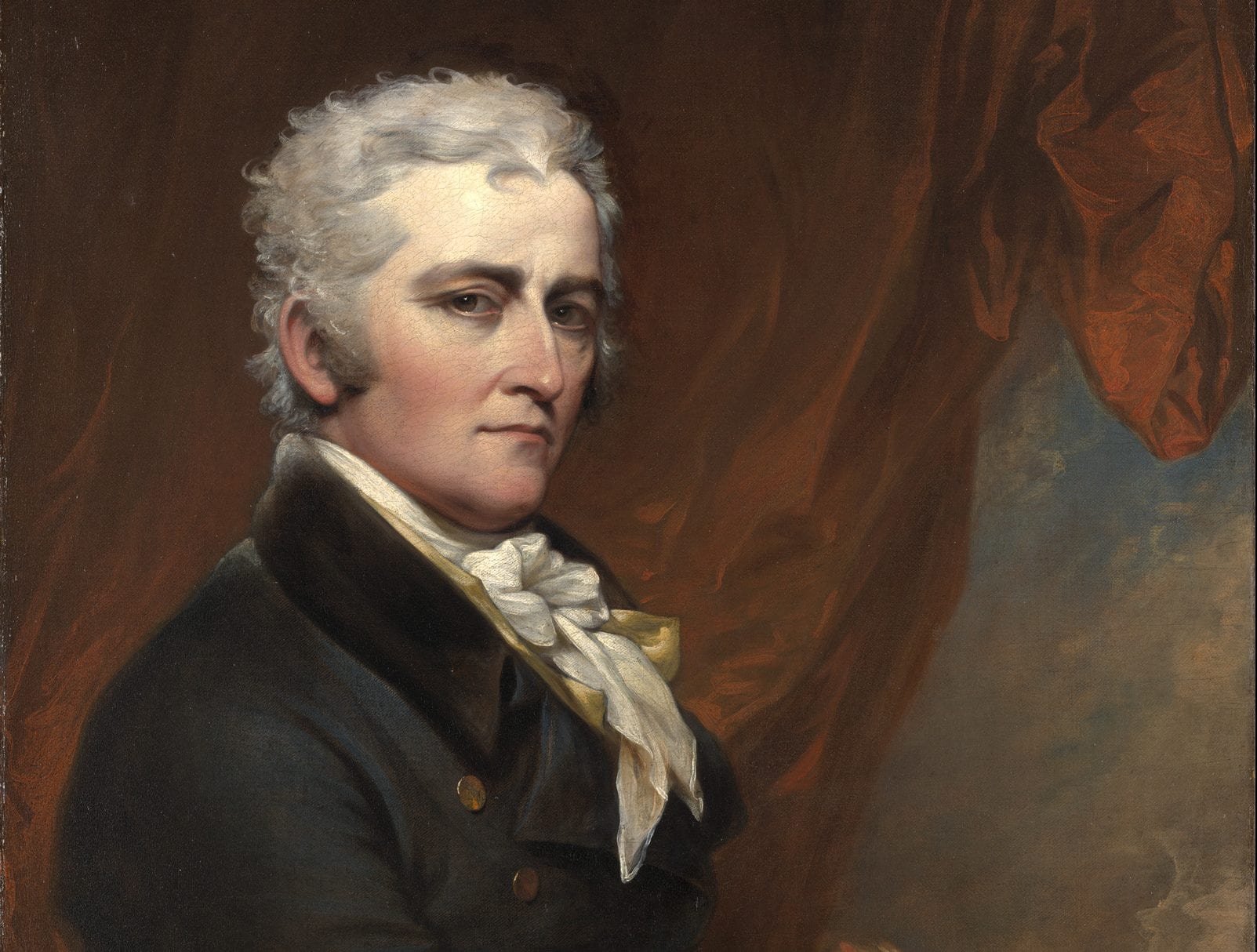

- 11. George Mason, Virginia

- 12. Charles Pinckney, South Carolina

- 13. William S. Johnson, Connecticut

- 14. Gunning Bedford Jr., Delaware

- 15. Elbridge Gerry, Massachusetts

A Foreign Spectator XXI

September 13, 1787

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)