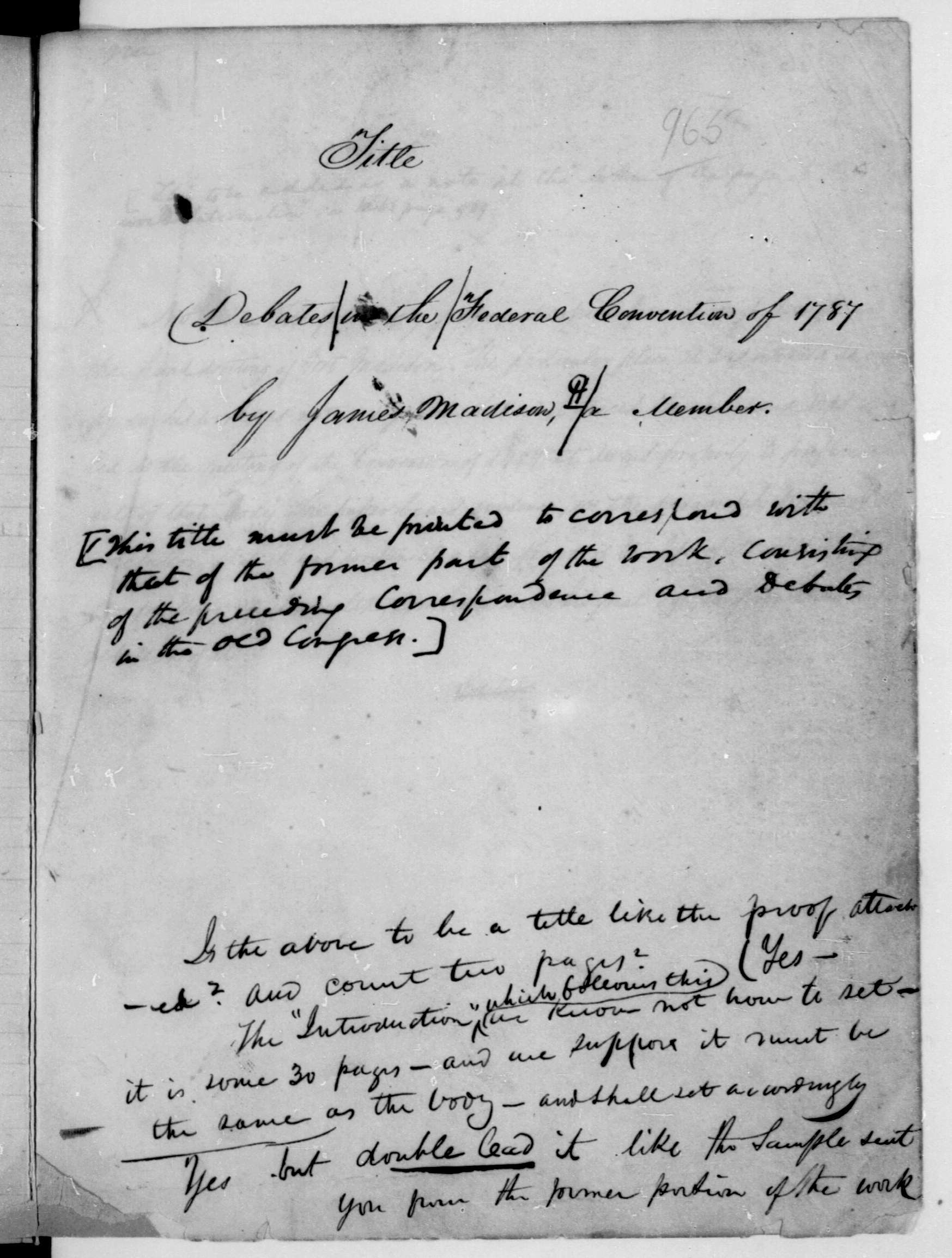

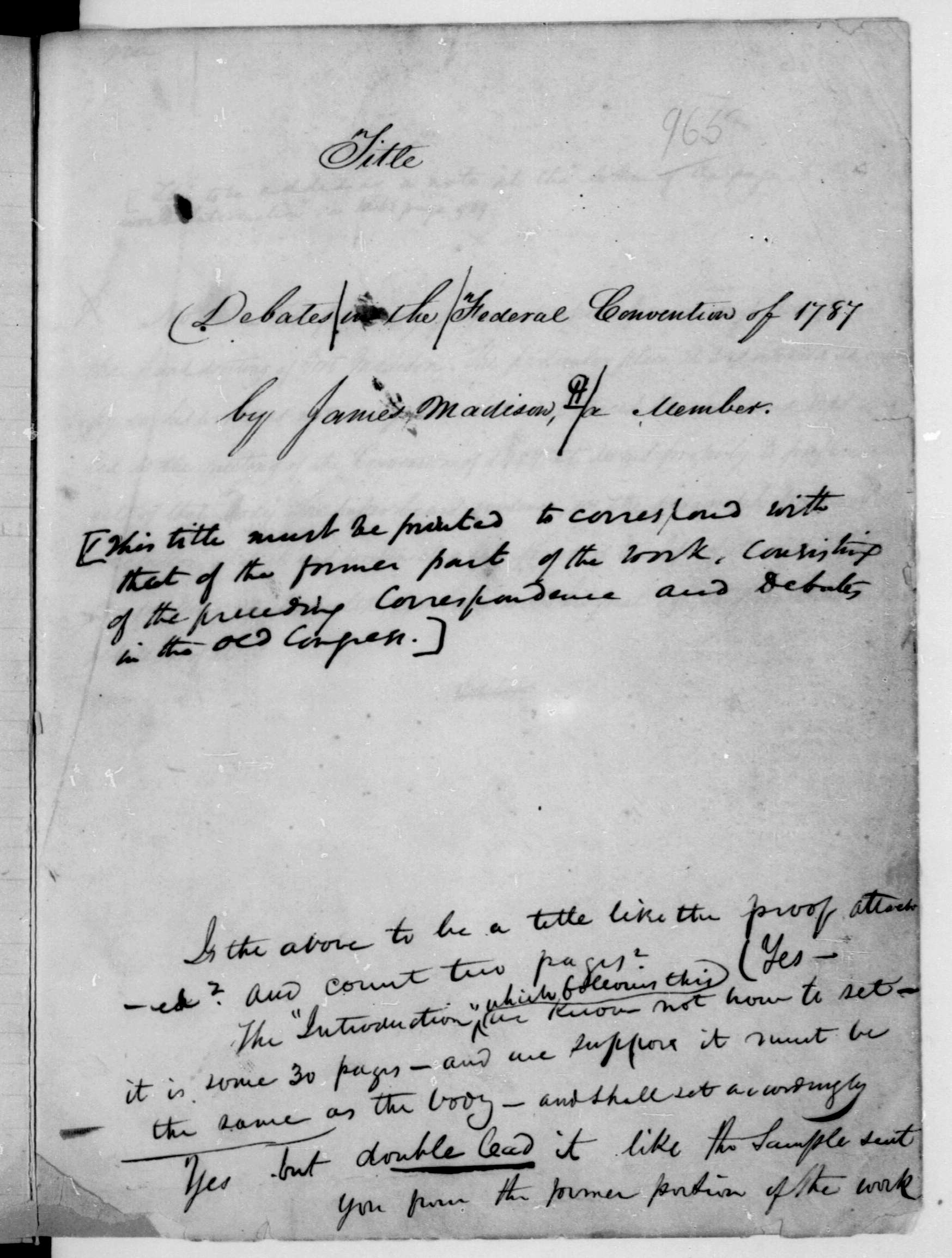

Introduction

An Old Whig, a prominent Pennsylvania Antifederalist whose identity is unknown, contended that the Constitution contains the potential to produce a consolidated government ruling over one large territory. Reflecting received opinion, he argued that such a government, would not remain republican. The only hope for republican government was to form a confederacy of the states. (It was this view that James Madison contended against in the Constitutional Convention, the Virginia Ratifying Convention (1788), and Federalist 10. He offered an alternative “science of politics,” accepting faction, which the republican tradition had deplored, as essential to preserving liberty in an extended republic.) The Old Whig also argued that given the power of the proposed government, a bill of rights was essential. He buttressed his case by appealing to the precedents in English history for such explicit guarantees of rights. In addition to appealing to the British tradition of due process, he also appealed to the new American claim to “natural liberty.” During the campaign over adoption of the Constitution, the appeal to “natural liberty” had a greater impact on the electorate than an appeal to the British tradition. It certainly had a greater impact on Madison in the First Congress (Madison Argues for a Bill of Rights (1789).

Source: From the Independent gazetteer: This is certainly a very important crisis to the people of America. Philadelphia, 1787. The Library of Congress; https://goo.gl/xYb6tS.

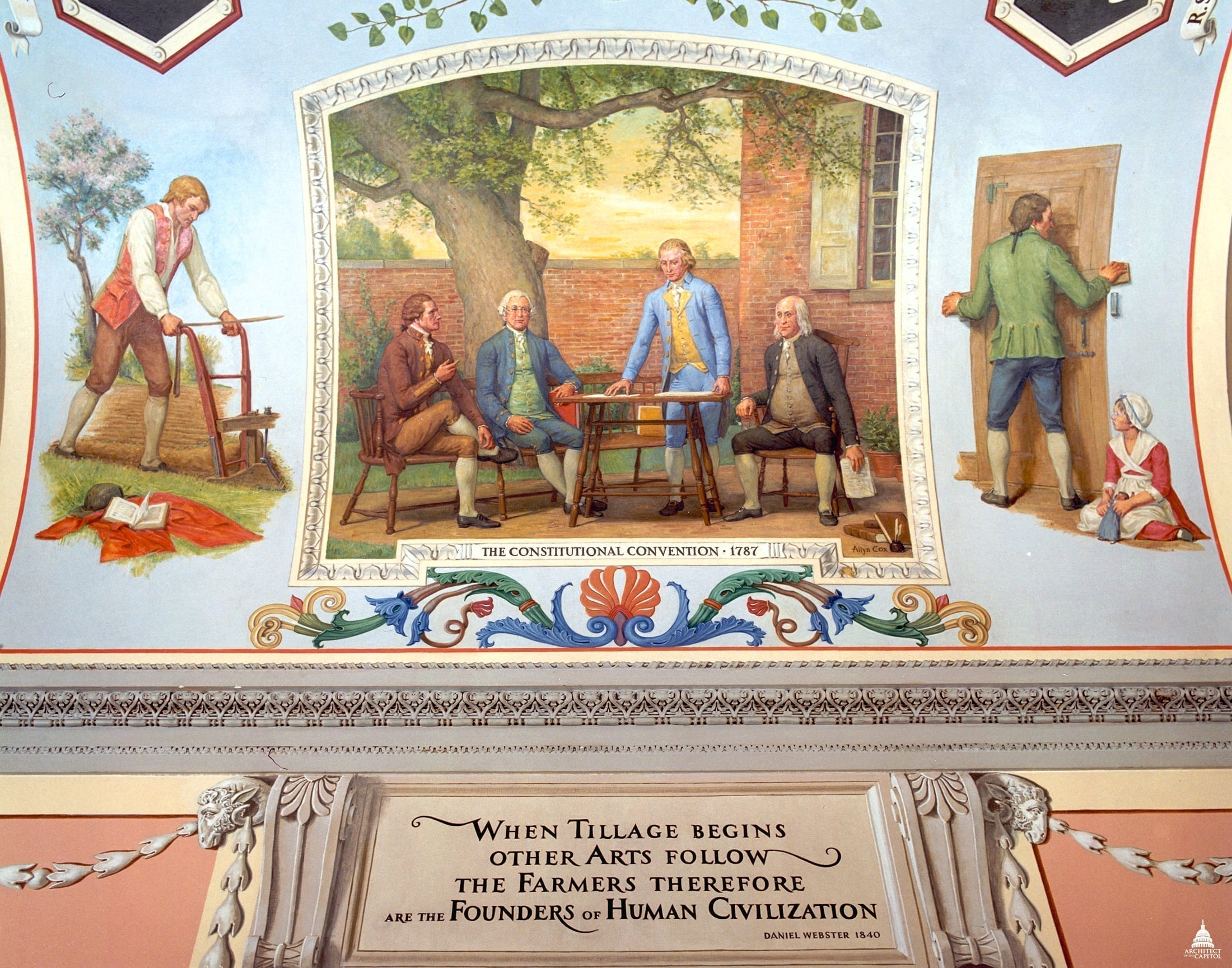

. . . It is beyond a doubt that the new federal Constitution, if adopted, will in a great measure destroy, if it does not totally annihilate, the separate governments of the several states. We shall, in effect become one great republic. Every measure of importance, will be continental. What will be the consequence of this? One thing is evident, that no republic of so great a magnitude, ever did, or ever can exist. But a few years elapsed, from the time in which ancient Rome extended her dominion beyond the bounds of Italy, until the downfall of her republic; and all political writers agree, that a republican government can exist only in a narrow territory: but a confederacy of different republics has, in many instances, existed and flourished for a long time together. The celebrated Helvetian League,[1] which exists at the moment in full vigor, and with unimpaired strength, whilst its origin may be traced to the confines of antiquity, is one, among many examples on this head; and at the same time furnishes an eminent proof of how much less importance it is that the constituent parts of a confederacy of republics may be rightly framed than it is that the confederacy itself should be rightly organized; for hardly any two of the Swiss cantons have the same form of government, and they are almost equally divided in their religious principles, which have so often rent asunder the firmest establishments.

A confederacy of republics must be the establishment in America, or we must cease altogether to retain the republican form of government. From the moment we become one great republic, either in form or substance, the period is very shortly removed, when we shall sink first into monarchy, and then into despotism. If there were no other fault in the proposed constitution, it must sink by its own weight. The continent of North America can no more be governed by one republic, than the fabled Atlas could support the heavens. Is it not worthy a few months labor to attempt rescuing this country from the despotism, which at this moment holds the best and fairest regions of the earth in thraldom and wretchedness? To attempt the forming a plan of confederation, which may enable us at once to support our continental union with vigor and efficacy, and to maintain the rights of the separate states and the invaluable liberty of the subject? These ideas of political felicity to some people may seem like the visions of a utopian fantasy; and I am persuaded that some amongst us have as little disposition to realize them, as they have to recollect the principles, which inspired us in our revolt from Great Britain. But there is at least, this consolation in aiming at excellence, that if we do not obtain our object, we can make considerable progress toward it.

The science of politics has very seldom had fair play. So much of passion, interest and temporary prospects of gain are mixed in the pursuit that a government has been much oftener established with a view to the particular advantages or necessities of a few individuals than to the permanent good of society. If the men who at different times have been entrusted to form plans of government for the world had been really actuated by no other views than a regard to the public good, the condition of human nature in all ages would have been widely different, from that which has been exhibited to us in history. In this country perhaps we are possessed of more than our share of political virtue. If we will exercise a little patience, and bestow our best endeavors on the business, I do not think it impossible, that we may yet form a federal constitution, much superior to any form of government, which has ever existed in the world; but whenever this important work shall be accomplished, I venture to pronounce that it will not be done without a careful attention to the framing of a bill of rights.

Much has been said and written, on the subject of a bill of rights; possibly without sufficient attention to the necessity of conveying distinct and precise ideas of the true meaning of a bill of rights. Your readers, I hope, will excuse me, if I conclude this letter with an attempt to throw some light on this subject.

Men when they enter into society yield up a part of their natural liberty, for the sake of being protected by government. If they yield up all their natural rights, they are absolute slaves to their governors. If they yield up less than is necessary, the government is so feeble that it cannot protect them. To yield up so much, as is necessary for the purposes of government; and to retain all beyond what is necessary is the great point, which ought, if possible, to be attained in the formation of a constitution. At the same time that by these means, the liberty of the subject is secured, the government is really strengthened; because wherever the subject is convinced that nothing more is required from him than what is necessary for the good of the community, he yields a cheerful obedience, which is more useful than the constrained service of slaves. To define what portion of his natural liberty, the subject shall at the time be entitled to retain is one great end of a bill of rights. To these may be added in a bill of rights some particular engagements of protection, on the part of the government. Without such a bill of rights firmly securing the privileges of the subject, the government is always in danger of degenerating into tyranny; for it is certainly true, that “in establishing the powers of government, the rulers are invested with every right and authority, which is not in explicit terms reserved.”[2] Hence it is that we find the patriots, in all ages of the world, so very solicitous to obtain explicit engagements from their rulers, stipulating expressly for the preservation of particular rights and privileges.

In different nations, we find different grants or reservations of privileges appealed to in the struggles between the rulers and the people, many of which in the different nations of Europe have long since been swallowed up and lost by time, or destroyed by the arbitrary hand of power. In England we find the people, with the barons at their head, exacting a solemn resignation of their rights from King John, in their celebrated Magna Carta,[3] which has many times renewed in Parliament, during the reigns of his successors. The petition of rights[4] was afterwards consented to by Charles the First, and contained a declaration of the liberties of the people. The habeas corpus act,[5] after the restoration of Charles the Second, the bill of rights,[6] which was obtained from the Prince and Princess of Orange on their accession to the throne, and the act of settlement,[7] at the accession of the Hanover family, are other instances to show the care and watchfulness of that nation to improve every opportunity of the reign of a weak prince, or the revolution in their government, to obtain the most explicit declaration in favor of their liberties. In like manner the people of the country, at the revolution, having all power in their own hands, in forming the constitutions of several states, took care to secure themselves by bills of rights, so as to prevent, as far as possible, the encroachments of their future rulers upon the rights of the people. Some of these rights are said to be unalienable, such as the rights of conscience: yet even these have been often invaded, where they have not been carefully secured by express and solemn bills and declarations in their favor.

Before we establish a government, whose acts will be THE SUPREME LAW OF THE LAND, and whose power will extend to almost every case without exception, we ought carefully to guard ourselves by a BILL OF RIGHTS, against the invasion of those liberties which it is essential for us to retain, which it is of no real use to government to strip us of; but which in the course of human events have been too often insulted with all the wantonness of an idle barbarity.

- 1. A confederacy of Swiss cantons that formed during the 13th century and collapsed in 1798.

- 2. See Return to Starting Point: New Jersey Plan, second paragraph.

- 3. Signed in 1215

- 4. The Petition of Right, 1628, was a statement by Parliament of the rights of Englishmen.

- 5. Passed by Parliament in 1679, the Habeas Corpus Act defined the common law right of freedom from arbitrary imprisonment.

- 6. An act of Parliament passed in 1689 declaring the rights of Englishmen, following the abdication of Charles II and the ascension to the throne by William and Mary, “the Prince and Princess of Orange.”

- 7. An act of Parliament passed in 1701, which established that future Kings or Queens would be Protestant.

Federalist 1

October 27, 1787

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)