No related resources

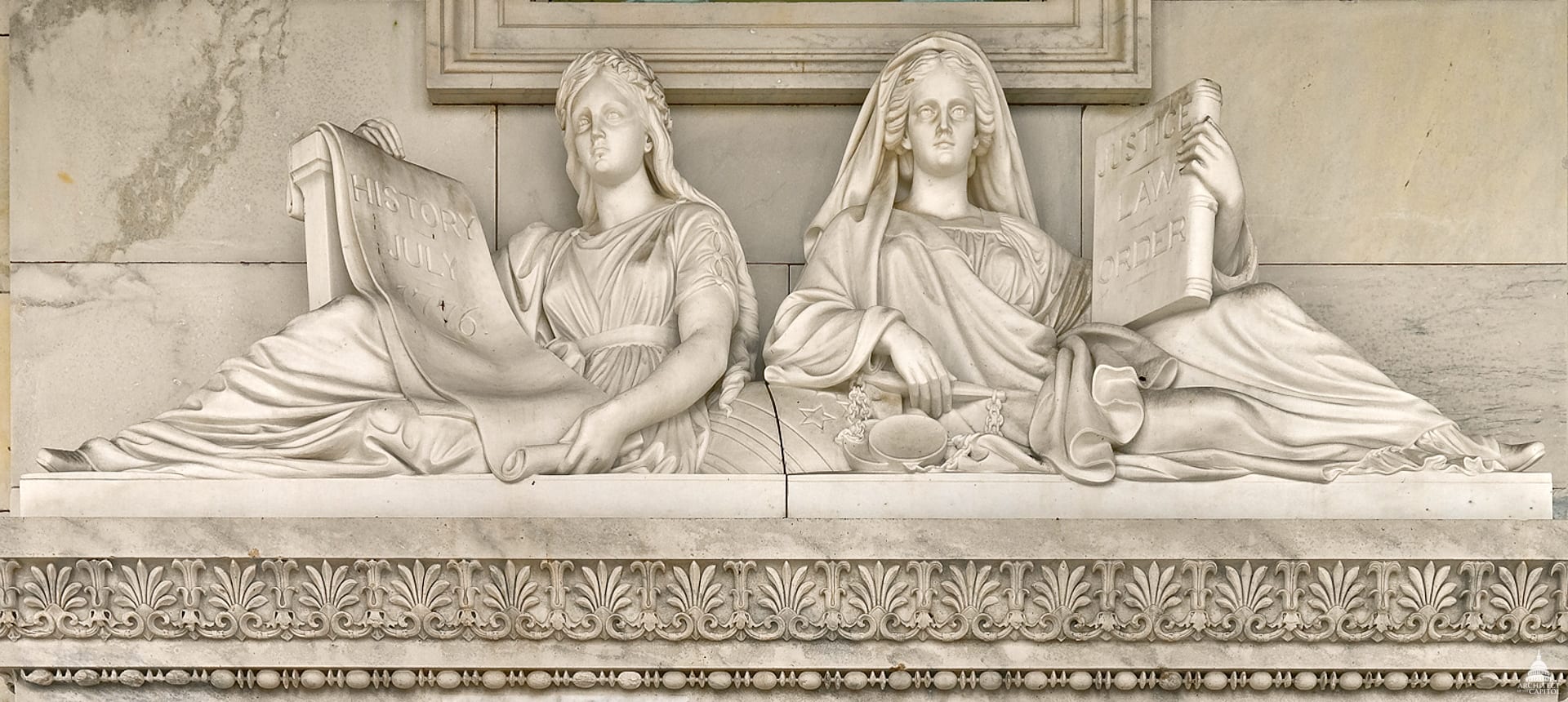

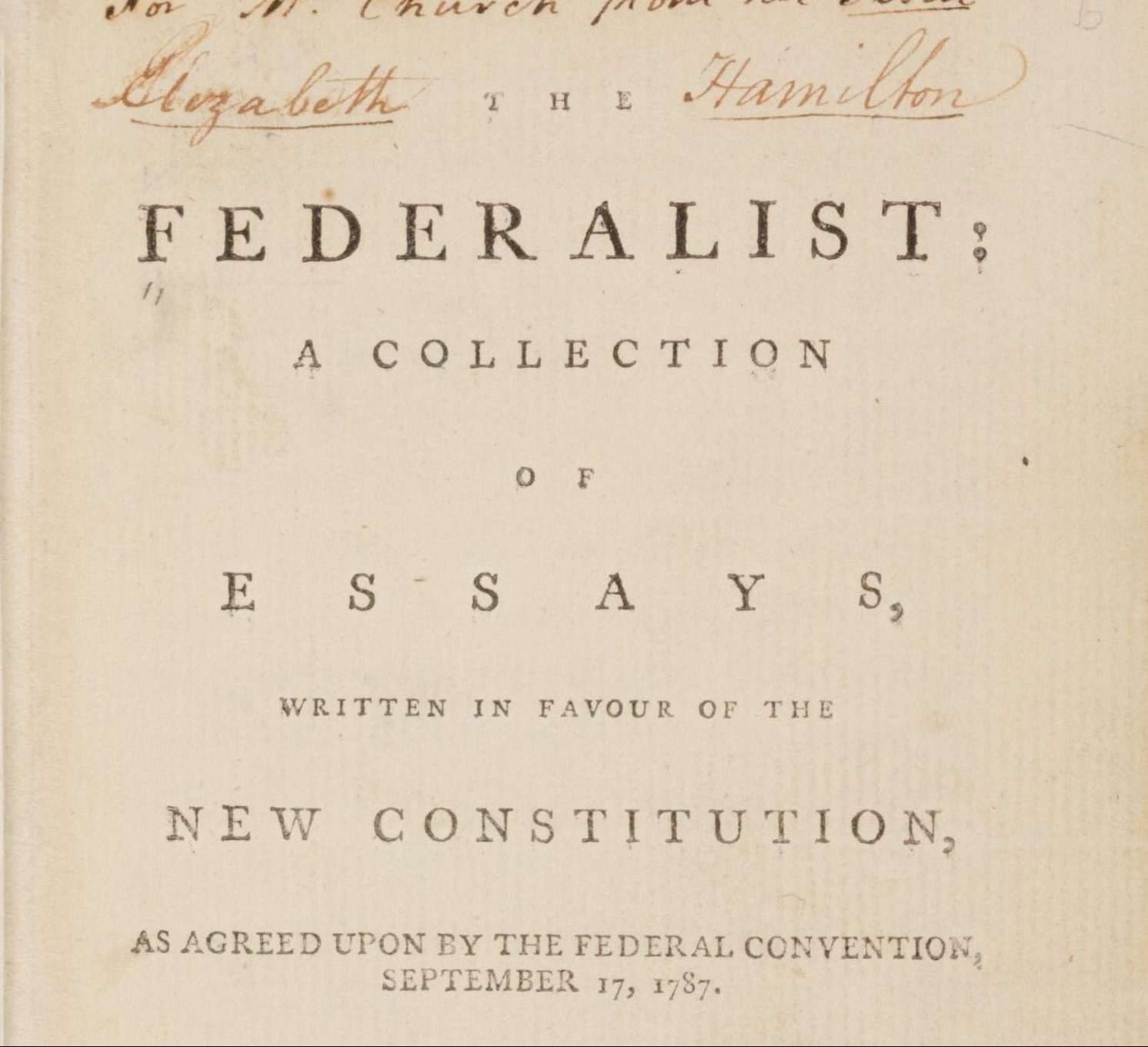

Introduction

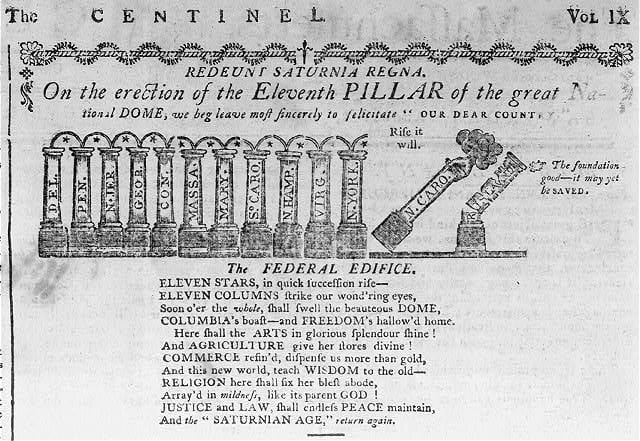

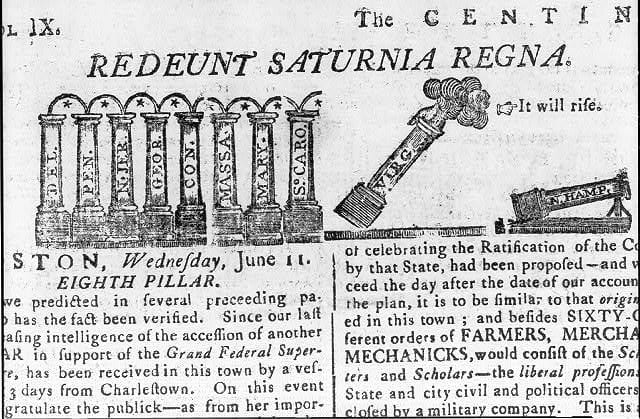

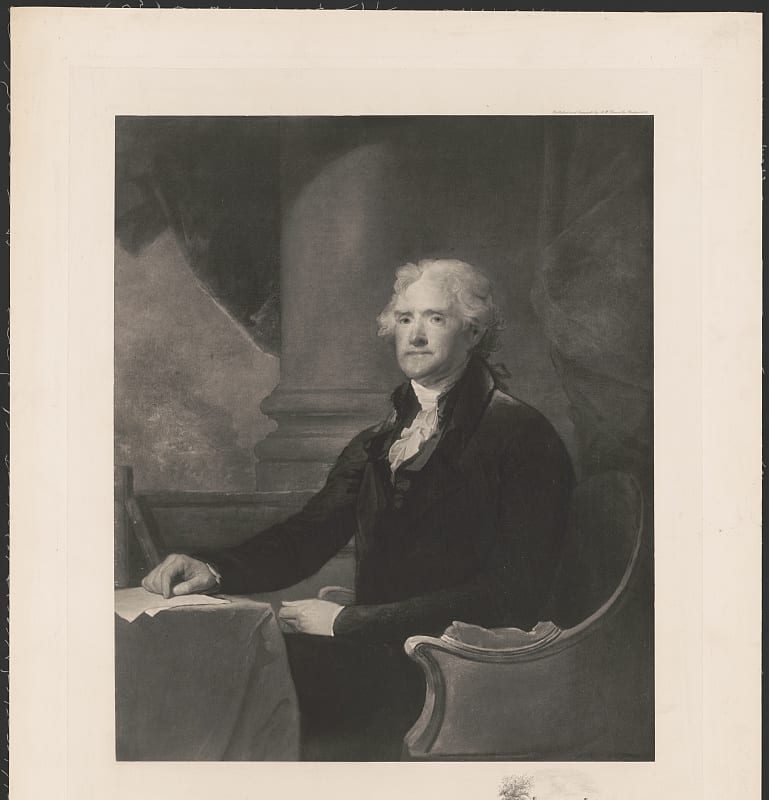

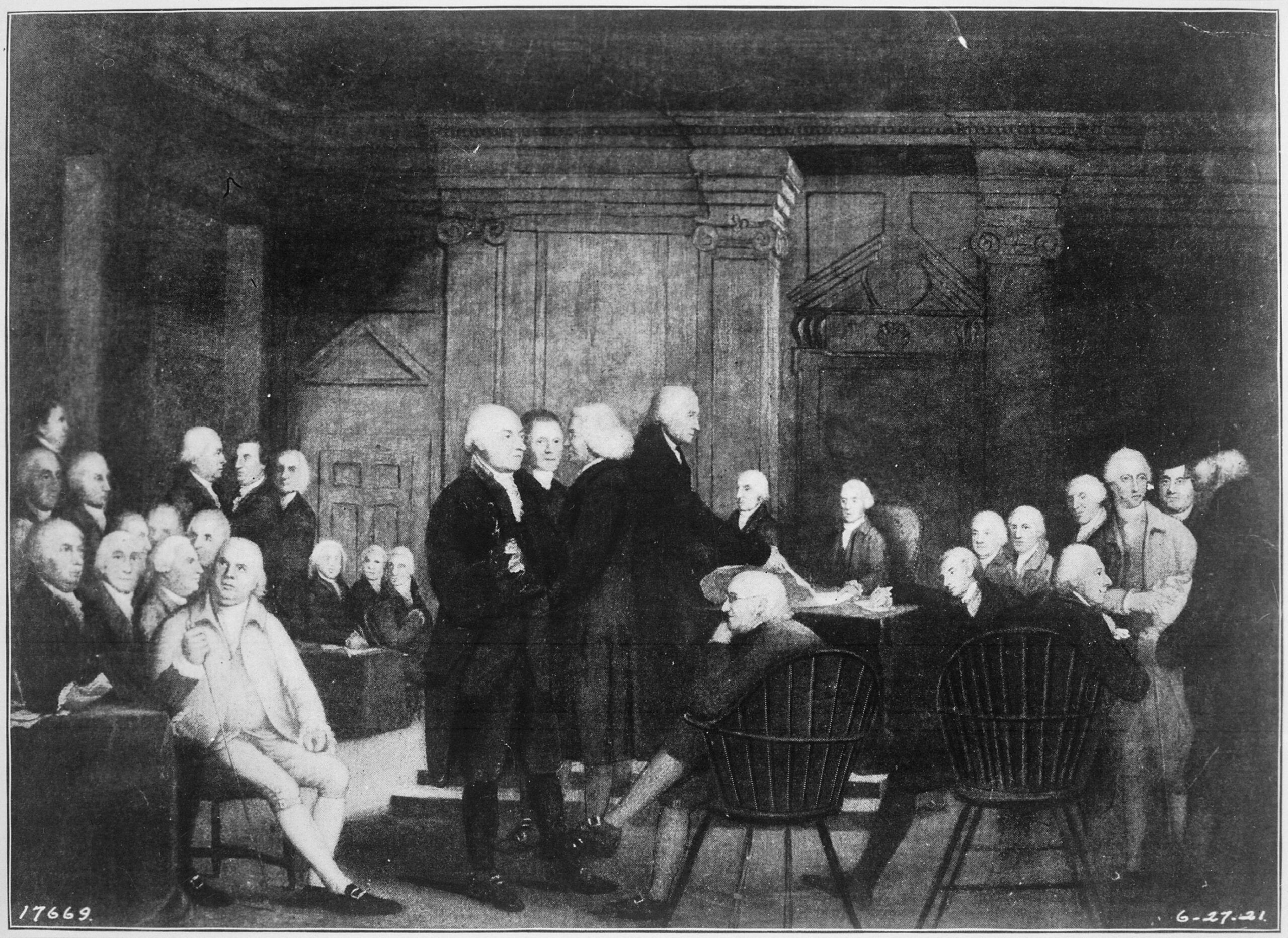

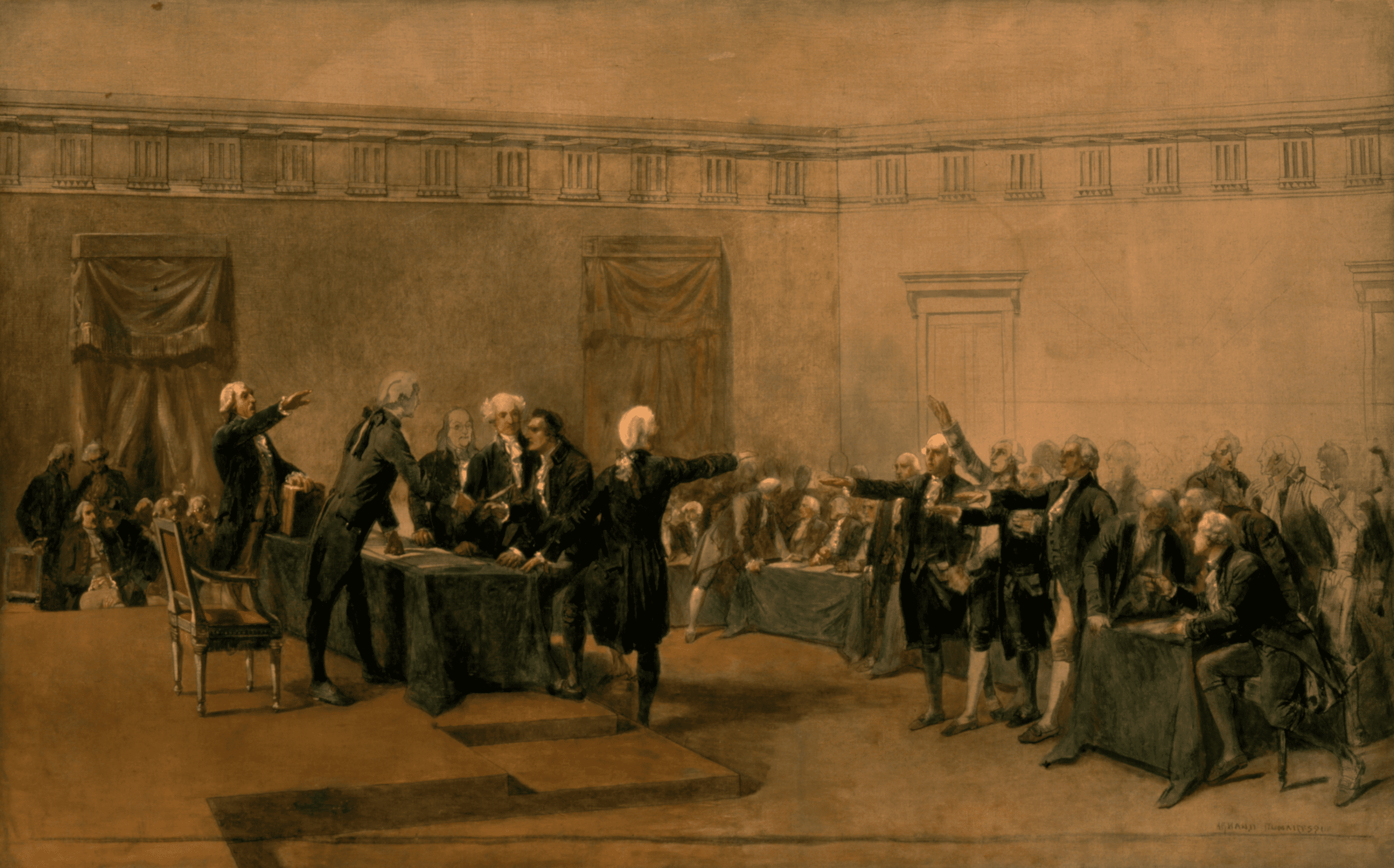

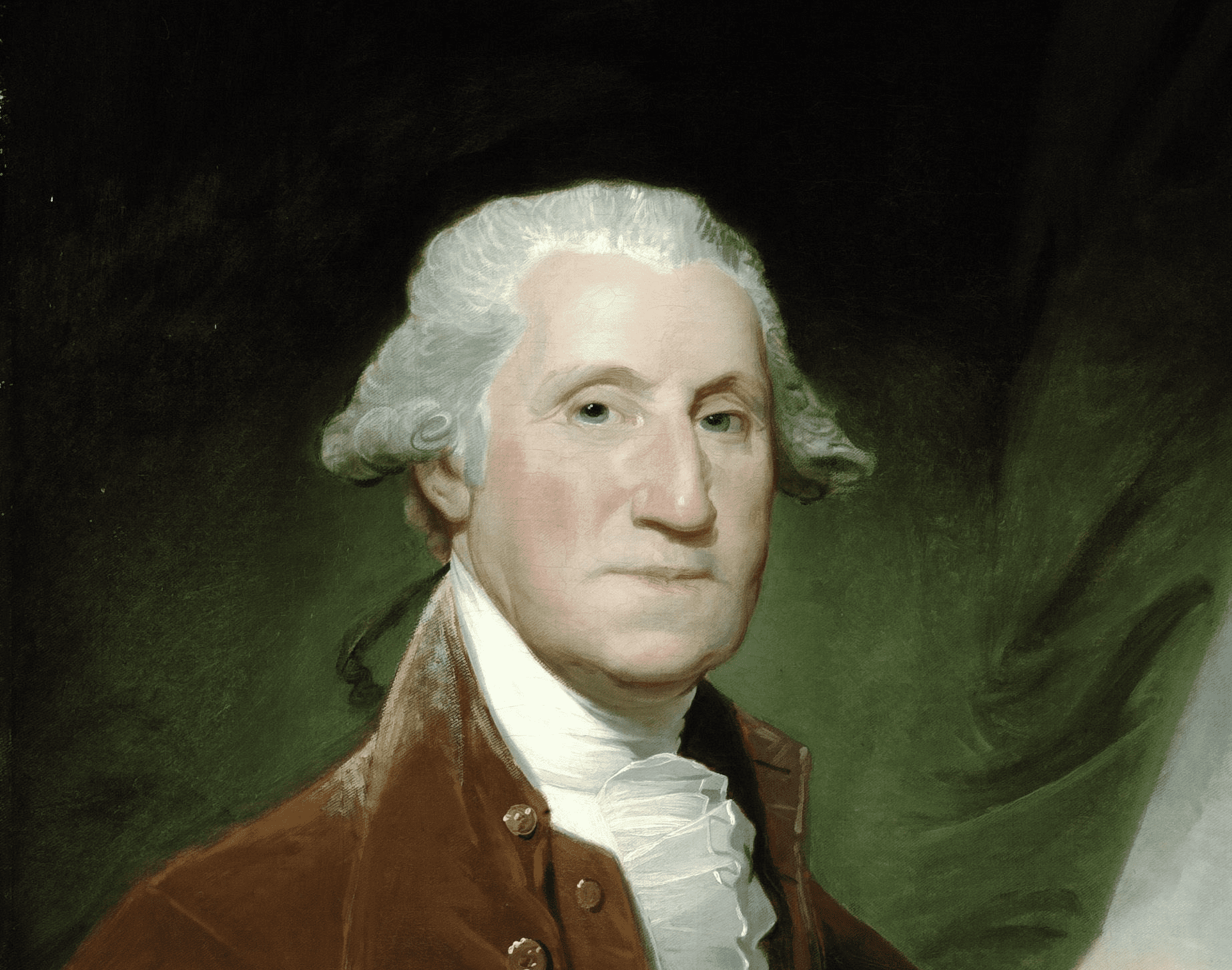

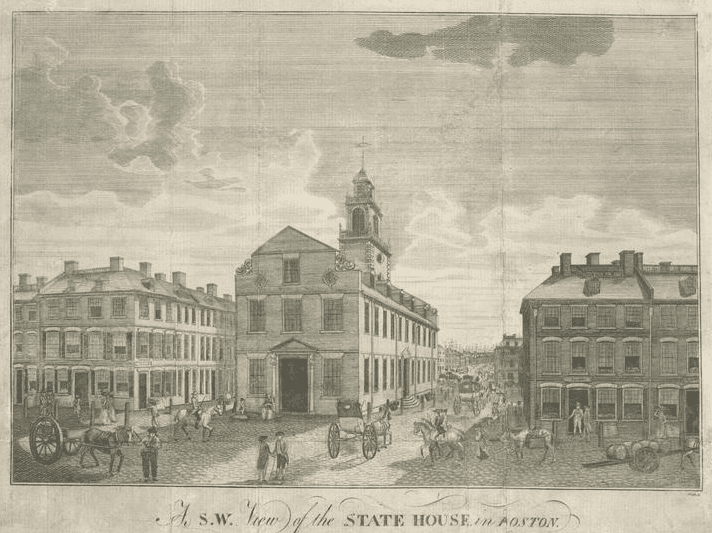

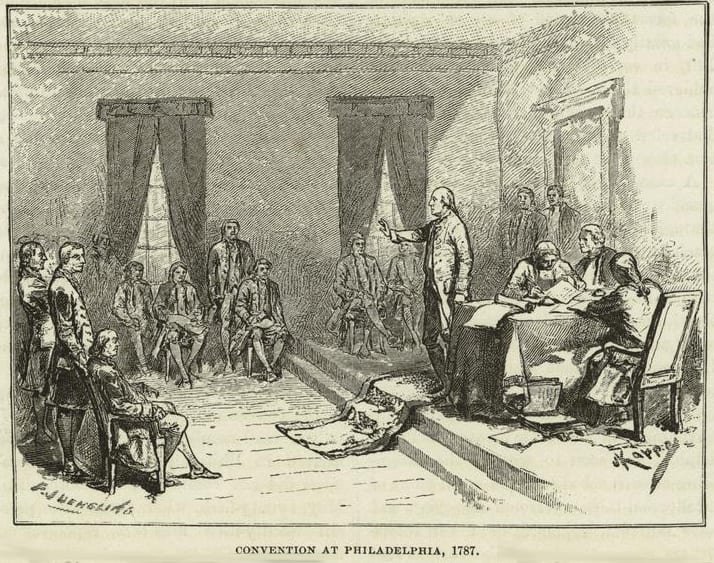

The June 6 vote on popular representation in the first branch was 8-3 in favor of the Virginia Plan (Connecticut, New Jersey, and South Carolina voted “no”). Madison (who authored the Virginia plan) had carried the day for popular election and representation in the first branch.

Yet the delegates voted against another resolution of the Virginia Plan that would have had the second branch elected by the first branch. With the question of how to constitute the second branch of the legislature remaining unsettled, the delegates examined other options. On June 7, the state delegations voted 10-0 in favor of a proposal that “the second branch of the national legislature be elected by the individual legislatures,” an option that Madison wholly disapproved.

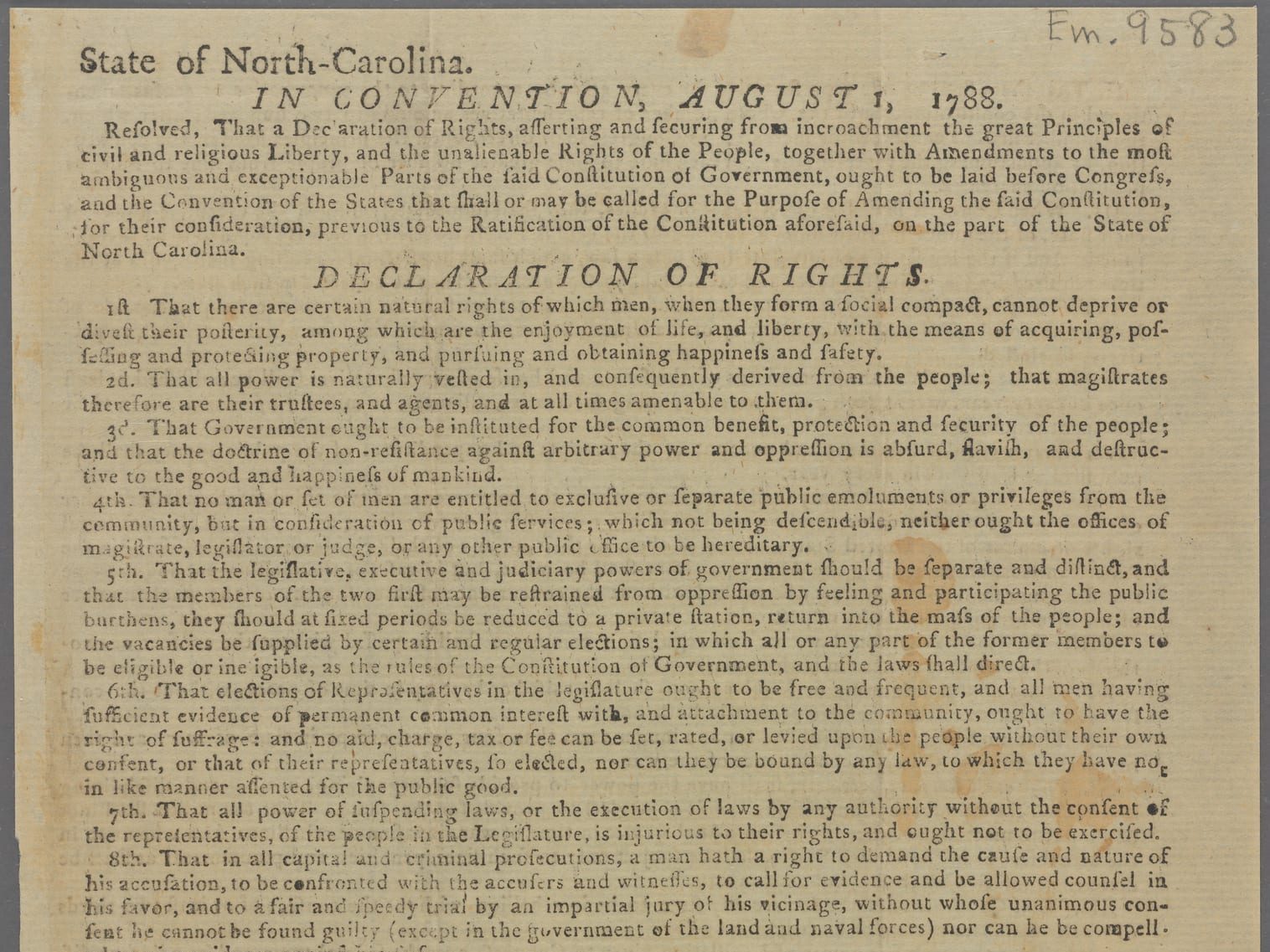

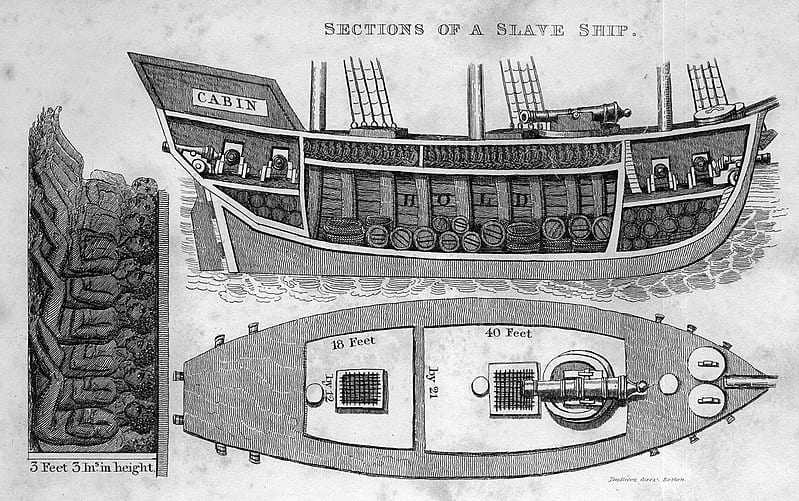

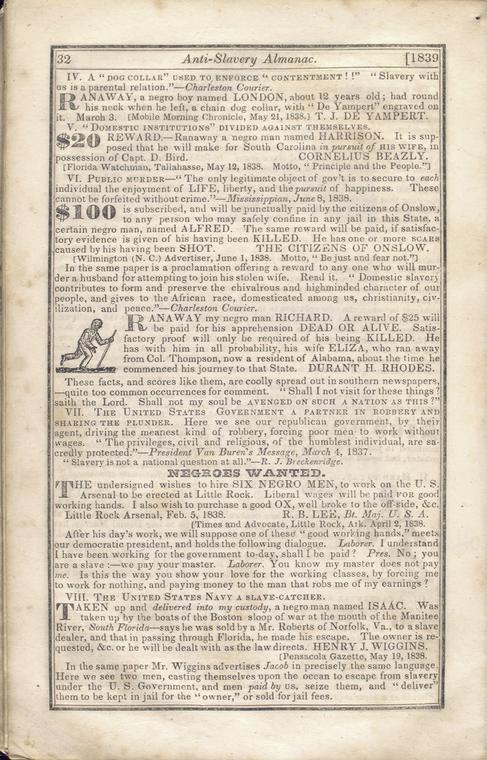

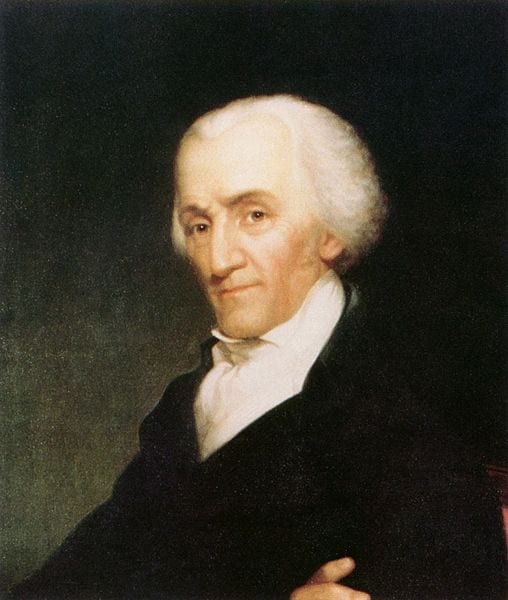

But a state-based election of the second branch was only one part of the equation. On June 11, Roger Sherman (a Connecticut delegate who would play a crucial role throughout the convention) asked for equal representation for each state in the second branch — a concession he thought reasonable in return for agreeing to proportional representation in the first branch. “Everything,” he said, “depended on this.” Sherman’s motion was rejected — for now — by a vote of 5 ayes to 6 noes. Delegates from South Carolina also introduced a third dimension to the discussion concerning representation in both branches. “Money was power,” said Pierce Butler. And, therefore, shouldn’t wealth be represented as well as people and states? The result was the introduction of the 3/5 clause, which, for purposes of allocating representation, counted three-fifths of the slave population in the overall population count. That this was a strange maneuver, counting only “property” in human beings as a representation of wealth, did not go unnoticed. As Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts asked, “Why . . . should the blacks, who were property in the South, be in the rule of representation more than the cattle and horses of the North?” Yet without recording further debate on the question, Madison recorded the vote on the proposed measure. Language counting “three fifths of all other persons” besides those described as “free” or “bound to servitude for a term of years” was adopted with reference to the first branch on a 9-2 vote, although only adopted in regard to the second branch (which at this point was still based on proportional representation) by a 6-5 vote.

On June 13, a committee presented an updated working draft of the Virginia Plan that preserved its original institutional structure but incorporated the two key changes decided by the Convention in the preceding days: that the members of the second legislative branch would be elected by the state legislatures (Resolution 4); and that when counting population for purposes of apportioning representatives to both branches, three-fifths of the slave population would be included (Resolutions 7 and 8).

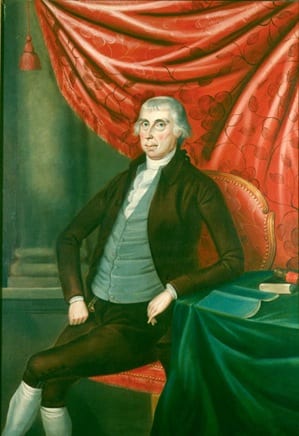

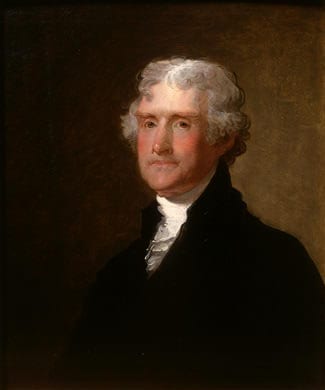

The three-fifths clause was incorporated into both branches of the legislature for the moment in order to secure the principle of popular representation. Consequently, the Constitution would now incorporate into the balancing of regional powers an implicit recognition of slavery, an institution that many, including several slaveholders in the Virginia delegation, abhorred and wished to see abolished. During the debates that would follow, delegates would voice their discomfort. Nevertheless, anticipating an eventual end to the institution that discredited American ideals, Madison, Sherman and others would insist on excluding the actual words “slave” and “slavery” from the language of the Constitution and on amending language implying federal recognition of slavery as lawful (The Slave Trade Clause (1787); The Fugitive Slave Clause, excerpt #6 (1787)).

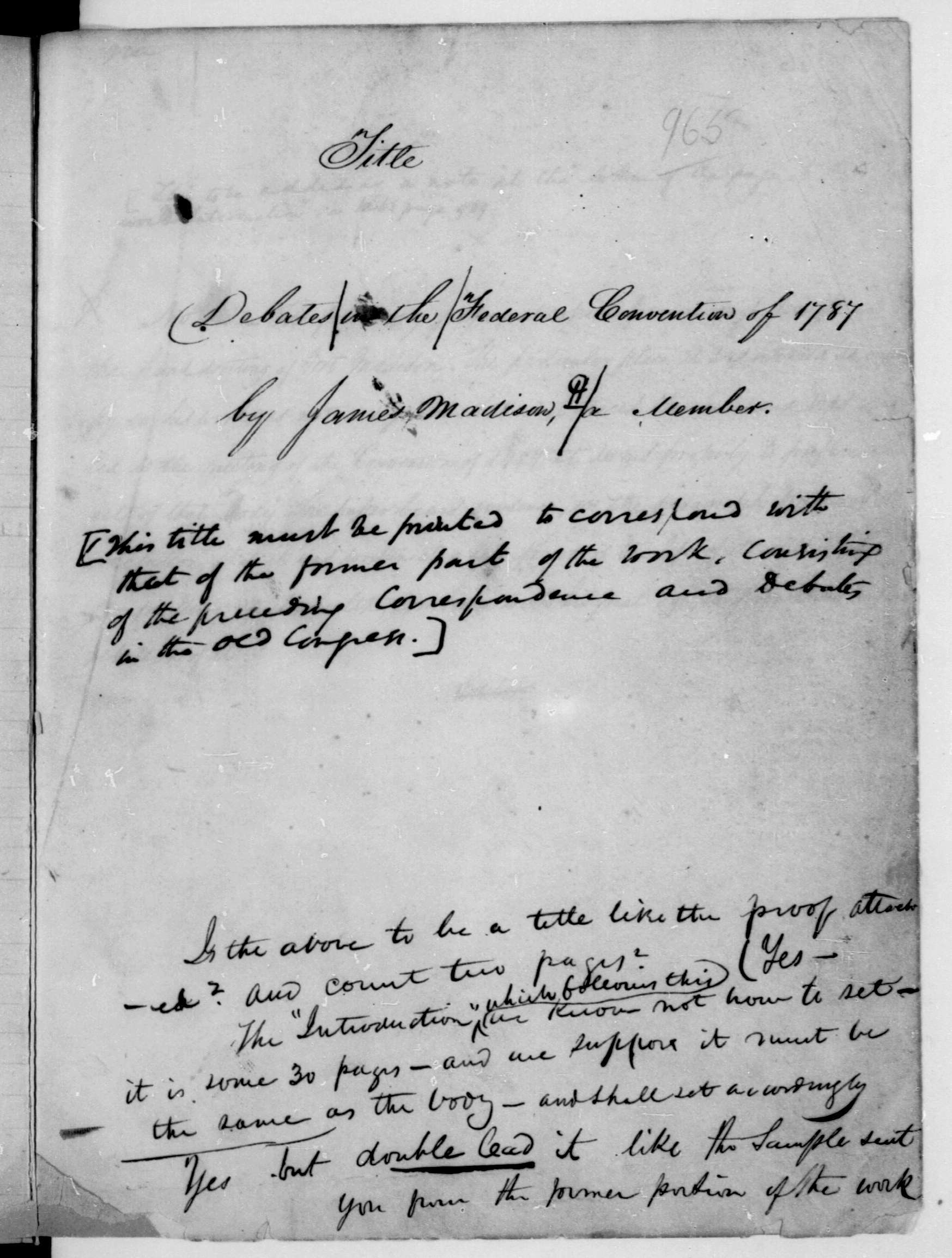

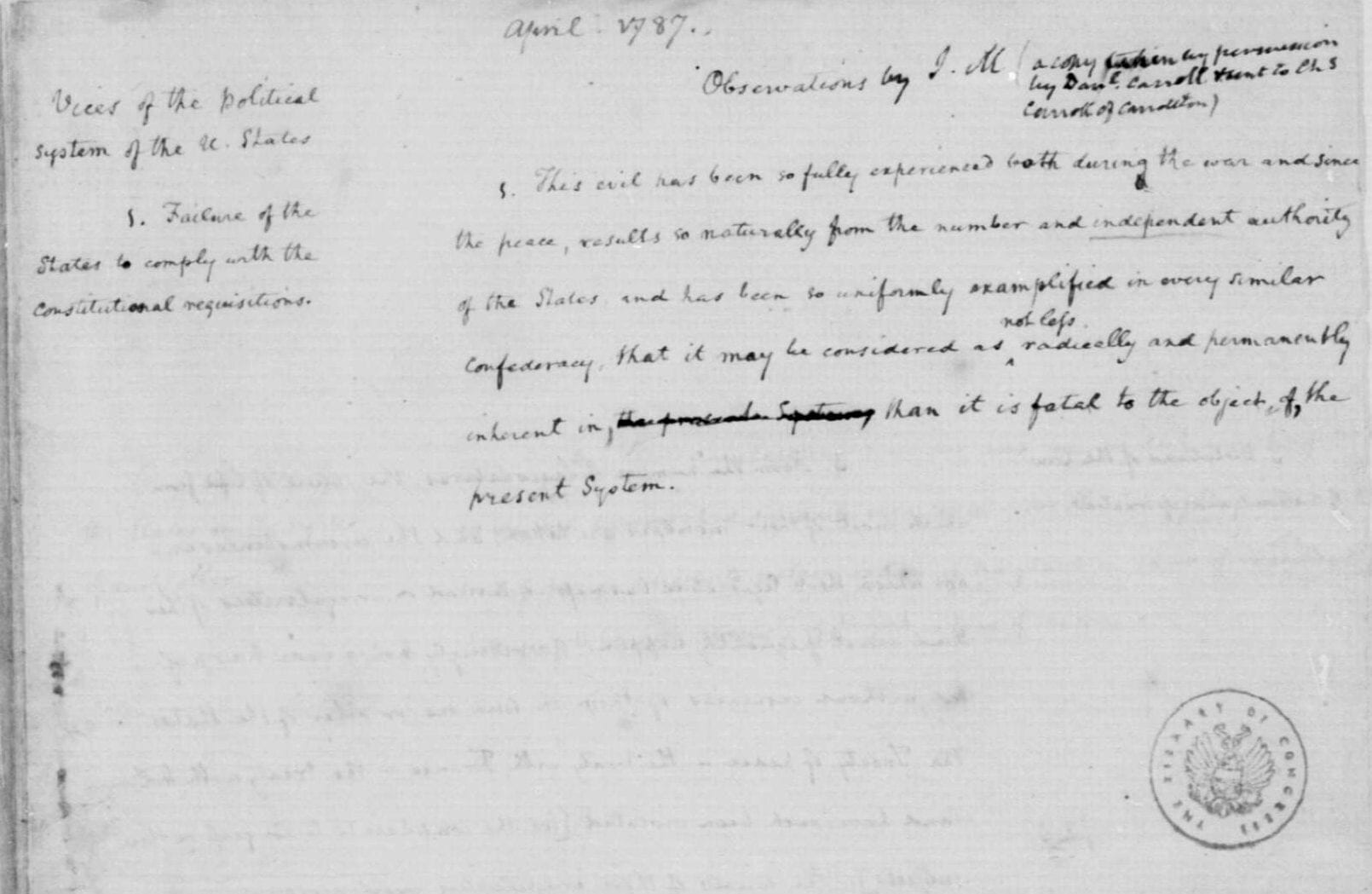

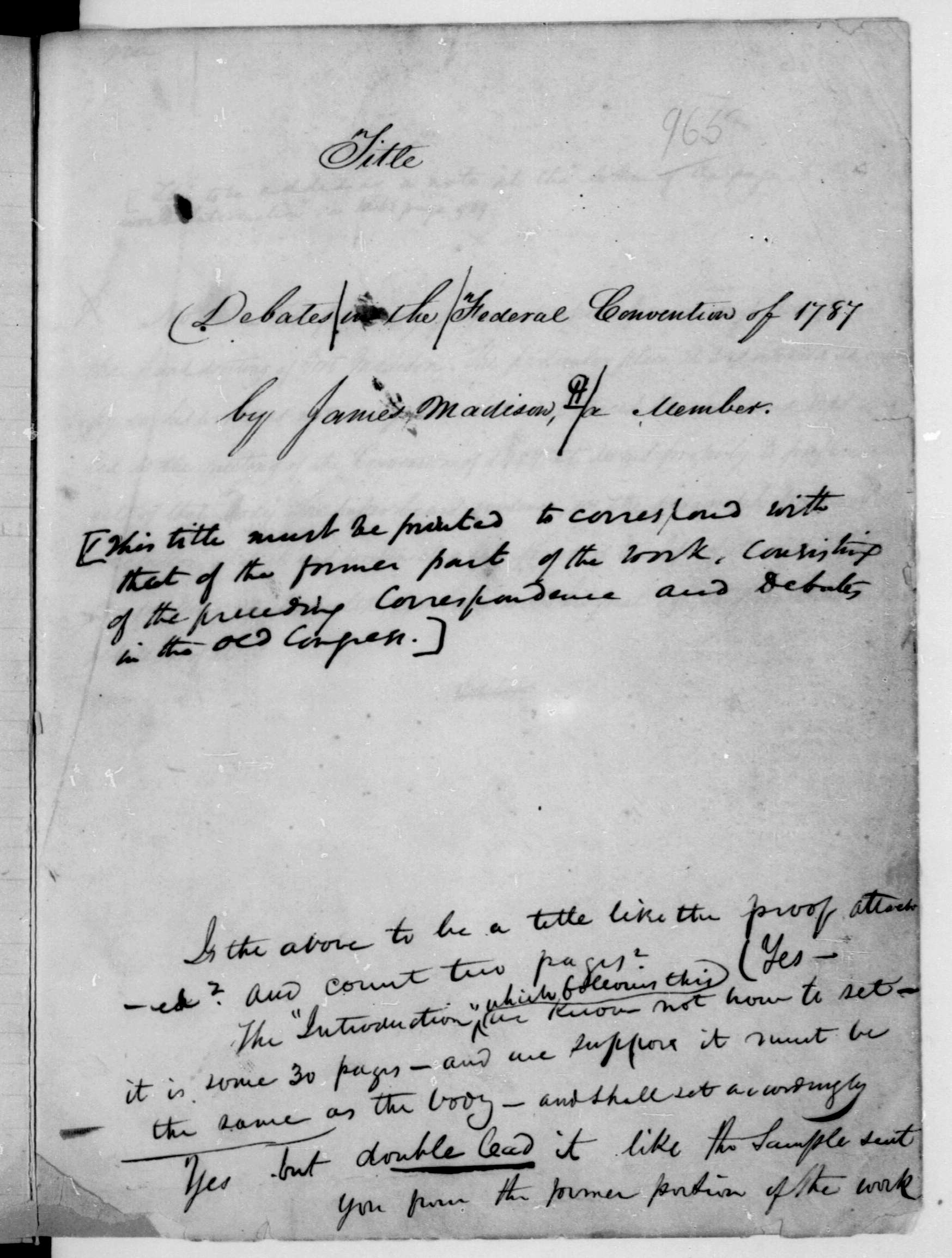

Source: Gordon Lloyd, ed., Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 by James Madison, a Member (Ashland, Ohio: Ashbrook Center, 2014), 77-86.

A Debate on Property | June 11

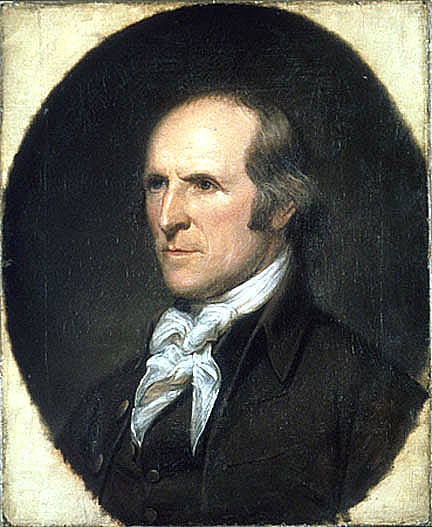

Mr. SHERMAN[1] proposed, that the proportion of suffrage in the first branch should be according to the respective numbers of free inhabitants; and that in the second branch, or Senate, each State should have one vote and no more. He said, as the States would remain possessed of certain individual rights, each State ought to be able to protect itself; otherwise, a few large States will rule the rest. The House of Lords in England, he observed, had certain particular rights under the Constitution, and hence they have an equal vote with the House of Commons, that they may be able to defend their rights.

Mr. RUTLEDGE[2] proposed, that the proportion of suffrage in the first branch should be according to the quotas of contribution. The justice of this rule, he said, could not be contested. Mr. BUTLER urged the same idea; adding, that money was power; and that the States ought to have weight in the government in proportion to their wealth.

Mr. KING[3] and Mr. WILSON[4] moved, “that the right of suffrage in the first branch of the National Legislature ought not to be according to the rule established in the Articles of Confederation, but according to some equitable ratio of representation.” The clause, so far as it related to suffrage in the first branch, was postponed, in order to consider this motion.

Mr. DICKINSON[5] contended for the actual contributions of the States, as the rule of their representation and suffrage in the first branch. By thus connecting the interests of the States with their duty, the latter would be sure to be performed.

Mr. KING remarked, that it was uncertain what mode might be used in levying a national revenue; but that it was probable, imposts would be one source of it. If the actual contributions were to be the rule, the non-importing States, as Connecticut and New Jersey, would be in a bad situation, indeed. It might so happen that they would have no representation. . . .

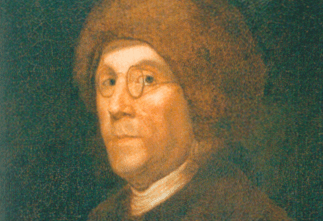

The question being about to be put, Doctor FRANKLIN[6] said, he had thrown his ideas of the matter on a paper, which Mr. WILSON read to the Committee in the words following:

“Mr. CHAIRMAN, — It has given me great pleasure to observe, that, till this point, the proportion of representation, came before us, our debates were carried on with great coolness and temper. If any thing of a contrary kind has on this occasion appeared, I hope it will not be repeated; for we are sent here to consult, not to contend, with each other; and declarations of a fixed opinion, and of determined resolution never to change it, neither enlighten nor convince us. Positiveness and warmth on one side naturally beget their like on the other, and tend to create and augment discord and division, in a great concern wherein harmony and union are extremely necessary to give weight to our councils, and render them effectual in promoting and securing the common good. . . .

“My learned colleague (Mr. WILSON) has already mentioned, that the present method of voting by States was submitted to originally by Congress under a conviction of its impropriety, inequality, and injustice. This appears in the words of their resolution. It is of the sixth of September, 1774. The words are:

“Resolved, that in determining questions in this Congress each Colony or Province shall have one vote; the Congress not being possessed of, or at present able to procure, materials for ascertaining the importance of each Colony.”

On the question for agreeing to Mr. KING’S and Mr. WILSON’S motion, it passed in the affirmative, — Massachusetts, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, aye — 7; New York, New Jersey, Delaware, no — 3; Maryland, divided.

It was then moved by Mr. RUTLEDGE, seconded by Mr. BUTLER, to add to the words, “equitable ratio of representation,” at the end of the motion just agreed to, the words “according to the quotas of contribution.”

On motion of Mr. WILSON, seconded by Mr. PINCKNEY, [7] this was postponed; in order to add, after the words, “equitable ratio of representation,” the words following: “in proportion to the whole number of white and other free citizens and inhabitants of every age, sex and condition, including those bound to servitude for a term of years, and three-fifths of all other persons not comprehended in the foregoing description, except Indians not paying taxes, in each State” — this being the rule in the act of Congress, agreed to by eleven States, for apportioning quotas of revenue on the States, and requiring a census only every five, seven, or ten years.

Mr. GERRY[8] thought property not the rule of representation. Why, then, should the blacks, who were property in the South, be in the rule of representation more than the cattle and horses of the North?

On the question, — Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, aye — 9; New Jersey, Delaware, no — 2.

Mr. SHERMAN moved, that a question be taken, whether each State shall have one vote in the second branch. Every thing, he said, depended on this. The smaller States would never agree to the plan on any other principle than an equality of suffrage in this branch. Mr. ELLSWORTH[9] seconded the motion.

On the question for allowing each State one vote in the second branch, — Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, aye — 5; Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, no — 6.

Mr. WILSON and Mr. HAMILTON moved, that the right of suffrage in the second branch ought to be according to the same rule as in the first branch.

On this question for making the ratio of representation, the same in the second as in the first branch, it passed in the affirmative, — Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, aye — 6; Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, no — 5. . . .

The Revised Virginia Plan | June 13

The Committee rose, and Mr. GORHAM[10] made a report, which was postponed till to-morrow, to give an opportunity for other plans to be proposed — the Report was in the words following:

- Resolved, that it is the opinion of this Committee, that a national Government ought to be established, consisting of a supreme Legislative, Executive and Judiciary.

- Resolved, that the National Legislature ought to consist of two branches.

- Resolved, that the members of the first branch of the National Legislature ought to be elected by the people of the several States for the term of three years; to receive fixed stipends by which they may be compensated for the devotion of their time to the public service, to be paid out of the National Treasury; to be ineligible to any office established by a particular State, or under the authority of the United States, (except those peculiarly belonging to the functions of the first branch,) during the term of service, and under the national Government for the space of one year after its expiration.

- Resolved, that the members of the second branch of the National Legislature ought to be chosen by the individual Legislatures; to be of the age of thirty years at least; to hold their offices for a term sufficient to insure their independence, namely, seven years; to receive fixed stipends by which they may be compensated for the devotion of their time to the public service, to be paid out of the National Treasury; to be ineligible to any office established by a particular State, or under the authority of the United States, (except those peculiarly belonging to the functions of the second branch,) during the term of service, and under the national Government, for the space of one year after its expiration.

- Resolved, that each branch ought to possess the right of originating acts.

- Resolved, that the National Legislature ought to be empowered to enjoy the legislative rights vested in Congress by the Confederation; and moreover to legislate in all cases to which the separate States are incompetent, or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual legislation; to negative all laws passed by the several States contravening, in the opinion of the National Legislature, the Articles of Union, or any treaties subsisting under the authority of the Union.

- Resolved, that the rights of suffrage in the first branch of the National Legislature, ought not to be according to the rule established in the Articles of Confederation, but according to some equitable ratio of representation, namely, in proportion to the whole number of white and other free citizens and inhabitants, of every age, sex and condition, including those bound to servitude for a term of years, and three-fifths of all other persons, not comprehended in the foregoing description, except Indians not paying taxes, in each State.

- Resolved, that the right of suffrage in the second branch of the National Legislature, ought to be according to the rule established for the first.

- Resolved, that a National Executive be instituted, to consist of a single person; to be chosen by the National Legislature, for the term of seven years; with power to carry into execution the national laws; to appoint to offices in cases not otherwise provided for; to be ineligible a second time; and to be removable on impeachment and conviction of malpractices or neglect of duty; to receive a fixed stipend by which he may be compensated for the devotion of his time to the public service, to be paid out of the National Treasury.

- Resolved, that the national Executive shall have a right to negative any legislative act which shall not be afterwards passed by two-thirds of each branch of the national Legislature.

- Resolved, that a national Judiciary be established, to consist of one supreme tribunal, the Judges of which shall be appointed by the second branch of the national Legislature, to hold their offices during good behavior, and to receive punctually, at stated times, a fixed compensation for their services, in which no increase or diminution shall be made, so as to affect the persons actually in office at the time of such increase or diminution.

- Resolved, that the national Legislature be empowered to appoint inferior tribunals.

- Resolved, that the jurisdiction of the national Judiciary shall extend to all cases which respect the collection of the national revenue, impeachments of any national officers, and questions which involve the national peace and harmony.

- Resolved, that provision ought to be made for the admission of States lawfully arising within the limits of the United States, whether from a voluntary junction of government and territory, or otherwise, with the consent of a number of voices in the national Legislature less than the whole.

- Resolved, that provision ought to be made for the continuance of Congress and their authorities and privileges, until a given day, after the reform of the Articles of Union shall be adopted, and for the completion of all their engagements.

- Resolved, that a republican constitution, and its existing laws, ought to be guaranteed to each State, by the United States.

- Resolved, that provision ought to be made for the amendment of the Articles of Union, when so ever it shall seem necessary.

- Resolved, that the Legislative, Executive and Judiciary powers within the several States, ought to be bound by oath to support the Articles of Union.

- Resolved, that the amendments which shall be offered to the Confederation by the Convention ought, at a proper time or times after the approbation of Congress, to be submitted to an assembly or assemblies recommended by the several Legislatures, to be expressly chosen by the people to consider and decide thereon.

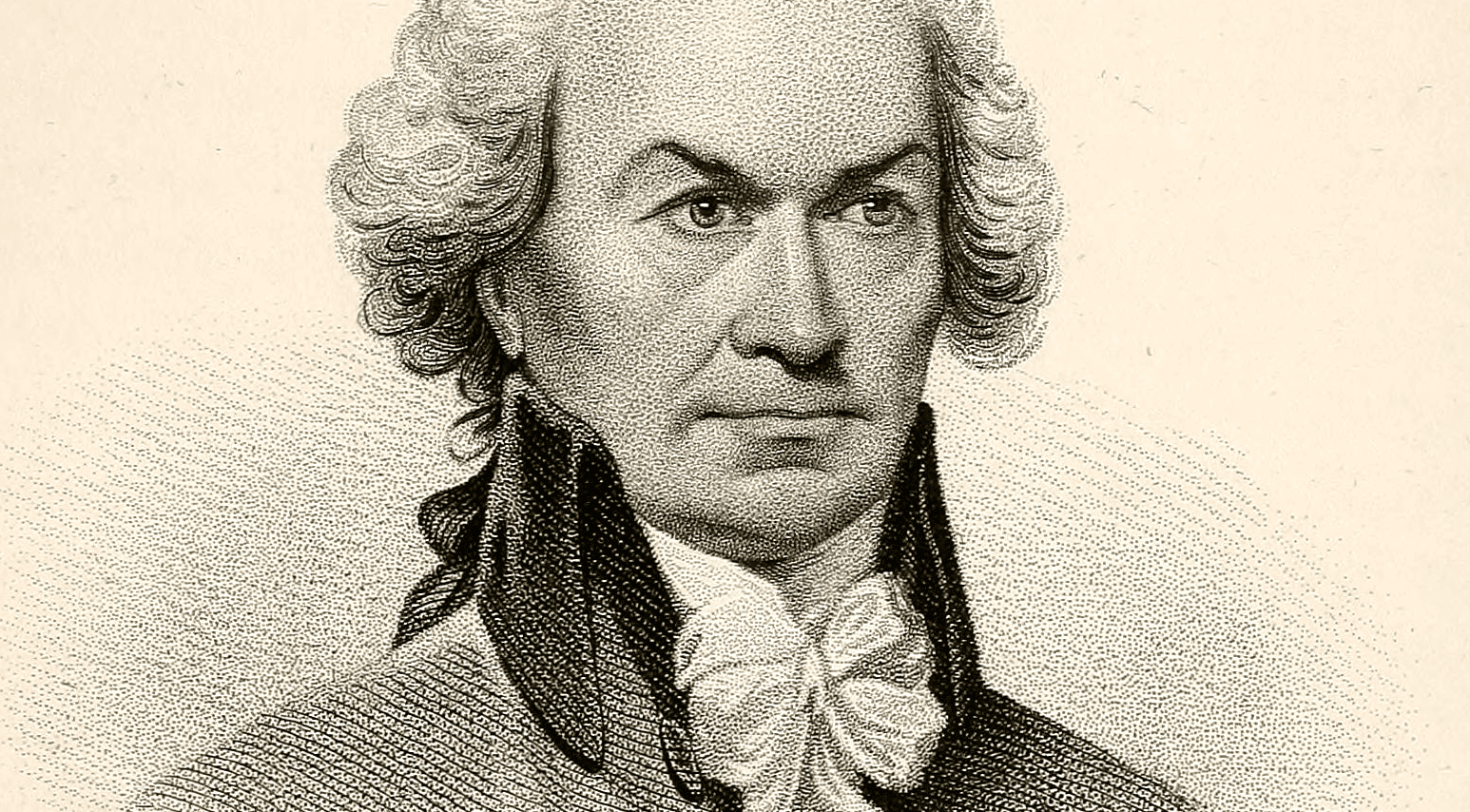

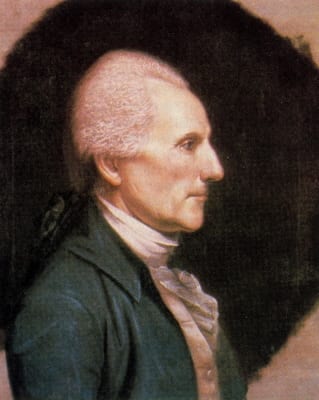

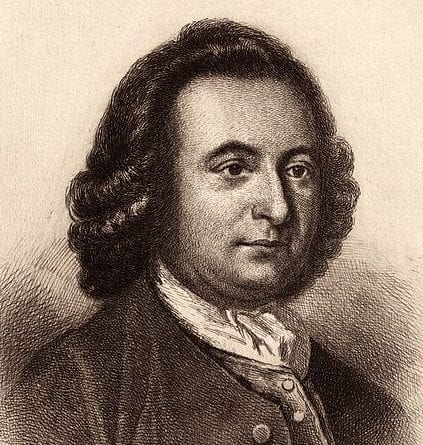

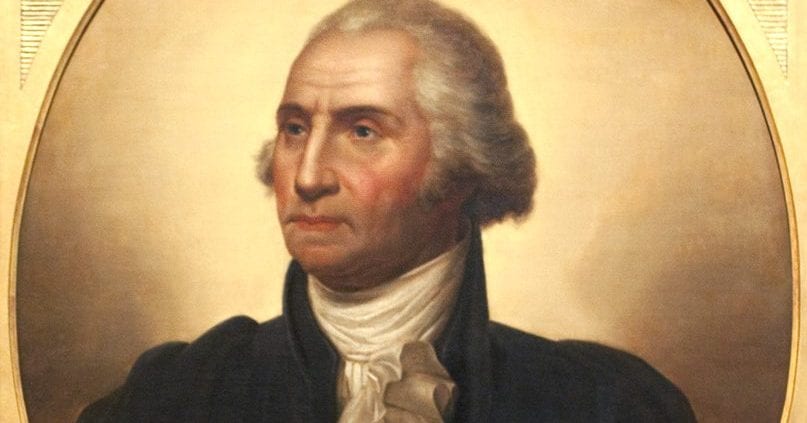

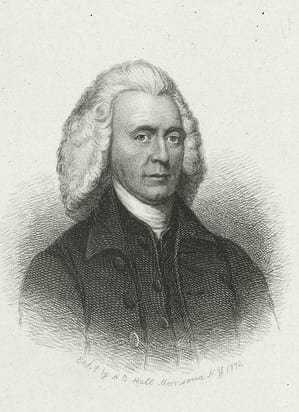

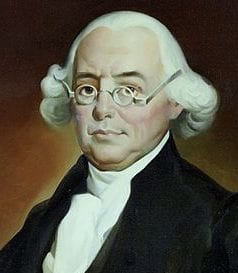

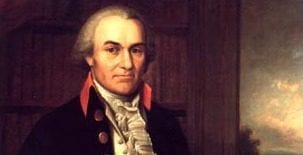

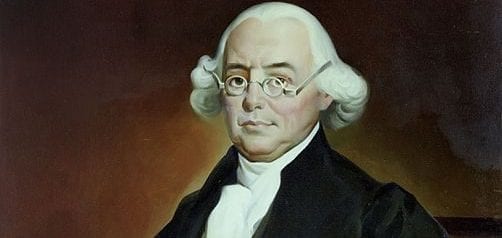

- 1. Roger Sherman of Connecticut

- 2. John Rutledge of South Carolina

- 3. Rufus King of Massachusetts

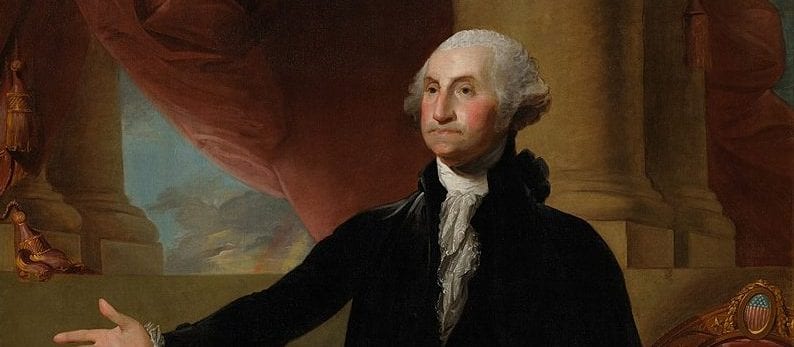

- 4. James Wilson of Pennsylvania

- 5. John Dickinson of Delaware

- 6. Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania

- 7. Charles Pinckney of South Carolina

- 8. Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts

- 9. Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut

- 10. Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)