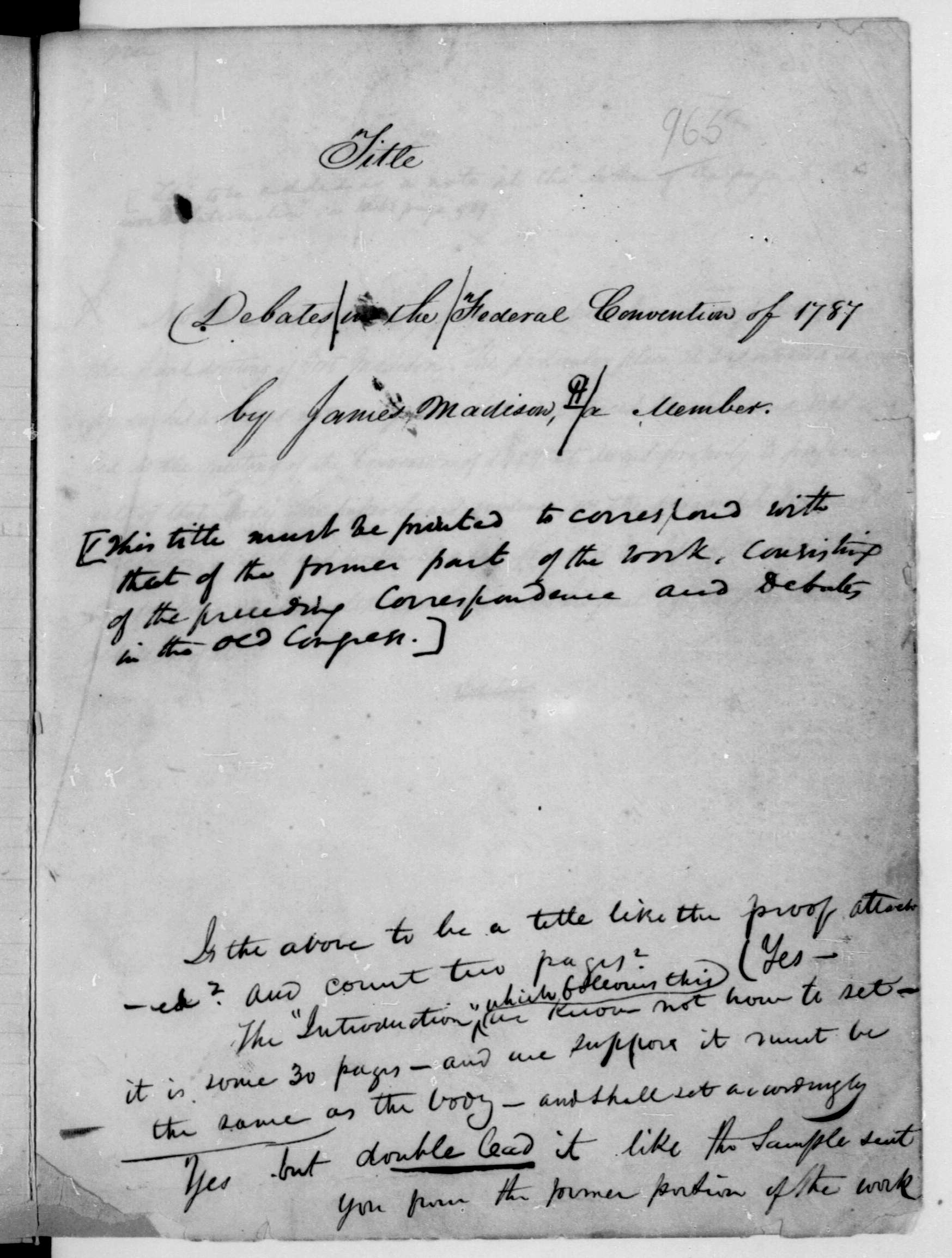

OBSERVATIONS ON THE CONSTITUTION

Proposed by the FEDERAL CONVENTION.

Thus happily mistaken was the ingenious, learned, and patriotic Lord Belhaven, in his prediction concerning the fate of his country; and thus happily mistaken, it is hoped, that some of our fellow-citizens will be, in their prediction concerning the fate of their country.

Had they taken larger scope, and assumed in their proposition the vicissitude of human affairs, and the passions that so often confound them, their prediction might have been a tolerably good guess. Amidst the mutabilities of terrestial things, the liberty of United America may be destroyed. As to that point, it is our duty, humbly, constantly, fervently, to implore the protection of our most gracious maker, “who doth not afflict willingly nor grieve the children of men,” and incessantly to strive, as we are commanded, to recommend ourselves to that protection, by “doing his will,” diligently exercising our reason in fulfilling the purposes for which that and our existence were given to us.

How the liberty of this country is to be destroyed, is another question. Here, the gentlemen assign a cause, in no manner proportioned, as it is apprehended, to the effect.

The uniform tenor of history is against them. That holds up the licentiousness of the people, and turbulent temper of some of the states, as the only causes to be dreaded, not the conspiracies of federal officers. Therefore, it is highly probable, that, if our liberty is ever subverted, it will be by one of the two causes first mentioned. Our tragedy will then have the same acts, with those of the nations that have gone before us; and we shall add one more example to the number already too great, of a people that would not take warning, not “know the things which belong to their peace. ” But, we ought not to pass such a sentence against our country, & the interests of freedom: Though, no sentence whatever can be equal to the atrocity of our guilt, if through enormity of obstinacy or baseness, we betray the cause of our posterity and of mankind, by providence committed to our parental and fraternal care. “Detur venia verbis”–The calamities of nations are the punishments of their sins!

As to the first mentioned cause, it seems unnecessary to say any more upon it.

As to the second, we find, that the misbehaviour of the constituent parts acting separately, or in partial confederacies, debilitated the Greeks under “the Amphictionic Council,” and under the Achaean League, and that this misbehaviour ruined Greece. As to the former, it was not entirely an assembly of strictly democratical republics. Besides, it wanted a sufficiently close connection of its parts. Tyrants and aristocracies sprung up. After these observations, we may call our attention from it.

’Tis true, the Achcean League was disturbed, by the misconduct of some parts, but, it is as true, that it surmounted these difficulties, and wonderfully prospered, until it was dissolved in the manner that has been described.

The glorious operations of its principles bear the clearest testimony to this distant age and people, that the wit of man never invented such an antidote against monarchical and aristocratical projects, as a strong combination of truly democratical republics. By strictly or truly democratical republics, the writer means republics, in which all the officers are from time to time chosen by the people.

The reason is plain. As liberty and equality, or as termed by Polybius, benignity, were the foundations of their institutions, and the energy of the government pervaded all the parts in things relating to the whole, it counteracted for the common welfare, the designs hatched by selfishness in separate councils.

If folly or wickedness prevailed in any parts, friendly offices and salutary measures restored tranquility. Thus the public good was maintained. In its very formation, tyrannies and aristocracies submitted, by consent or compulsion. Thus, the Ceraunians, Trezenians, Epidaurians, Megalopolitans, Argives, Hermionians, and Phlyarians, were received into the league. A happy exchange! For history informs us, that so true were they to their noble and benevolent principles, that, in their diet, “no resolutions were taken, but what were equally advantageous to the whole confederacy, and the interest of each part so consulted, as to leave no room for complaints.”

How degrading would be the thought to a citizen of United America, that the people of these states, with institutions beyond comparison preferable to those of the Achcean league, and so vast a superiority in other respects, should not have wisdom & virtue enough, to manage their affairs, with as much prudence and affection of one for another, as these antients did.

Would this be doing justice to our country? The composition of her temper is excellent, and seems to be acknowledged equal to that of any nation in the world. Her prudence will guard its warmth against two faults, to which it may be exposed–The one an imitation of foreign fashions, which from small things may lead to great. May her citizens aspire at a national dignity in every part of conduct, private as well as public. This will be influenced by the former. May simplicity be the characteristic feature of their manners, which inlaid in their other virtues and their forms of government, may then indeed be compared, in the eastern stile, to “apples of gold in pictures of silver.” Thus will they long, and may they, while their rivers run, escape the curse” of luxury–the issue of innocence debauched by folly, and the lineal predecessor of tyranny generated in rape and incest. The other fault, of which, as yet, there are no symptoms among us, is the thirst of empire. This is a vice, that ever has been, and from the nature of things, ever must be, fatal to republican forms of government. Our wants, are sources of happiness: our desires, of misery. The abuse of prosperity, is rebellion against Heaven: and succeeds accordingly.

Do the propositions of gentlemen who object, offer to our view, any of the great points upon which, the fate, fame, or freedom of nations has turned, excepting what some of them have said about trial by jury, which has been frequently and fully answered? Is there one of them calculated to regulate, and if needful, to controul, those tempers and measures of constituent parts of an union, that have been so baneful to the weal of every confederacy that has existed? Do not some of them tend to enervate the authority evidently designed thus to regulate and controul? Do not others of them discover a bias in their advocates to particular connections, that if indulged to them, would enable persons of less understanding and virtue, to repeat the disorders, that have so often violated public peace and honor? Taking them altogether, would they afford as strong a security to our liberty, as the frequent election of the federal officers by the people, and the repartition of power among those officers, according to the proposed system?

It may be answered, that, they would be an additional security. In reply, let the writer be permitted at present to refer to what has been said.

The principal argument of gentlemen who object, involves a direct proof of the point contended for by the writer of this address, and as far as it may be supposed to be founded, a plain confirmation of Historic evidence.

They generally agree, that the great danger of a monarchy or aristocracy among us, will arise from the federal senate.

The members of this senate, are to be chosen by men exercising the sovereignty of their respective states. These men therefore, must be monarchically or aristocratically disposed, before they will chuse federal senators thus disposed; and what merits particular attention, is, that these men must have obtained an overbearing influence in their respective states, before they could with such disposition arrive at the exercise of the sovereignty in them: or else, the like disposition must be prevalent among the people of such states.

Taking the case either way, is not this a disorder in parts of the union, and ought it not to be rectified by the rest? Is it reasonable to expect, that the disease will seize all at the same time? If it is not, ought not the sound to possess a right and power, by which they may prevent the infection from spreading.

From the annals of mankind, these conclusions are deducible–that states together may act prudently and honestly, and a part foolishly and knavishly; but, that it is a defiance of all probability, to suppose, that states conjointly shall act with folly and wickedness, and yet separately with wisdom and virtue.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)