The Hartford Convention: Secession or Reform?

Rumors were swirling throughout New England. What were the delegates, gathered in secret, doing? Were spies and war opponents, known as “Blue Lights,” aiding and abetting the enemy by flashing signals to guide blockade runners? Was secession under consideration? Worse, was treason? This threat to the Union was neither the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 nor the Nullification Crisis of the 1830s. This crisis was the Hartford Convention in December of 1814. New England delegates had assembled in Hartford, Connecticut, at the behest of wealthy Federalists who demanded the region organize a protest against the United States’ war with Great Britain, a contest they derided as “Mr. Madison’s War.” Both the Embargo Acts of the Jefferson Administration and the War of 1812 were unpopular with New England merchants economically dependent upon strong trade with Great Britain.

Fears of disunion haunted the founding generation and continued in the Early Republic. Alexander Hamilton, writing as Publius in the Federalist Papers, outlined in Federalist 1 a series of essays supporting the ratification of the Constitution in 1787. The first six essays stressed the importance of the Union, focusing on its “utility” for protecting the nation’s people against domestic and foreign foes. The Whiskey Rebellion demonstrated that a united nation had the strength to put down a domestic uprising. Washington believed a failure to do so might tempt the western farmers protesting the whiskey excise tax to call for a separate confederacy. Washington also warned his fellow citizens of the dangers of excessive partisanship in his famous Farewell Address. He was concerned that parties might become divided along sectional lines and threaten disunion. The nation faced such a question in the winter of 1814-15. Could the government conduct a war in the face of significant opposition from the large and economically powerful New England region?

Historians generally agree that secession was not on the table in Hartford, nor was treason. The evidence for this conclusion can be found in the Report of the Hartford Convention. The delegates called for reformation in the form of amendments to the Constitution. The report argues that disunion “should, if possible, be the work of peaceable times and deliberate consent” – circumstances not present in the midst of war and partisan bickering. “A severance of the union by one or more states,” the report continues, ” against the will of the rest, and especially in a time of war, can only be justified by absolute necessity.” The delegates claimed common ground with President Washington’s Farewell Address in warning against “precipitate measures tending to disunite the States” (Document E).

However, a consistent theme in United States history is where to draw the dividing line between federal power and state power. Chapter 9 of Documents and Debates in American History and Government gathers documents from the time of the Hartford Convention to examine this question. Like the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, written to protest the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, the Hartford Convention exemplifies state efforts to claim the right to judge the constitutionality of federal legislation. Study Questions included in this chapter ask students to consider the grievances raised by convention delegates, the role they saw “for the states in evaluating the constitutionality of acts of Congress,” and how we might evaluate their actions today. Were the Hartford Convention delegates engaged in a legitimate protest against federal government policy, or were they approaching “the confines of treason?” (Document D).

Documents in this chapter include:

- Noah Webster, The Origin of the Hartford Convention,1843

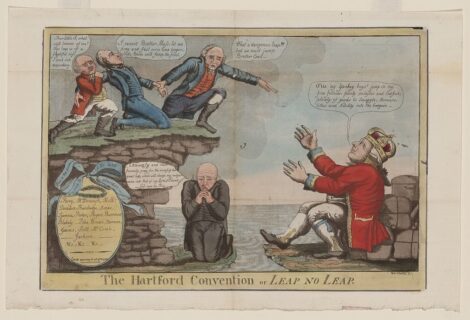

- William Charles, Leap or No Leap, c. 1814

- John Adams to William Plumer, December 4, 1814

- William H. Crawford to Jonathan Fisk, New England “approaches the confines of treason,” December 8, 1814

- Report of the Hartford Convention, 1815

We have also provided audio recordings of the chapter’s Introduction, Documents, and Study Questions. You’ll find these recordings at the top of the online version of each chapter. The recordings support literacy development for struggling readers and the comprehension of challenging text for all students.