Springfield Bids Goodbye to President-Elect Abraham Lincoln

Few of us enjoy particular attention on the day before our birthdays. Yet on the morning before Abraham Lincoln’s 52nd birthday—February 11, 1861—over a thousand of his neighbors gathered at the Springfield, Illinois train station to bid him farewell. Lincoln was embarking on a circuitous 12-day journey to Washington, DC, where he would complete his preparations to assume office as the 16th President of the United States.

His route would take him through larger cities where crowds of well-wishers lined the streets, waving flags as he disembarked to give simple speeches. In between stops, he had plenty to ponder. During the three months since his election, seven southern states had seceded from the Union. Representatives of the seceding states were already meeting in Montgomery, Alabama to draft the constitution of the Confederacy. On the same day Lincoln left Springfield, Jefferson Davis left his home in Mississippi to travel to Montgomery, where he would be inaugurated Confederate president. Lincoln and his party, insisting that secession was impermissible under the Constitution of the United States, observed the effort to organize a Southern nation with rising anxiety. Lincoln did not want to precipitate a civil war, but he also wanted to avoid any deal that would prevent war at the cost of acceding to the Southern demand that slavery be extended into new federal territories.

As Doris Kearns Goodwin recounts in Team of Rivals, Lincoln had for weeks been cultivating his cabinet choices, inviting potential appointees to visit him in Springfield for long, frank talks. Among those he hoped to recruit to his cabinet were three of his rivals for the 1860 Republican Presidential nomination: Senator William Seward of New York, an eloquent orator and influential leader among former Whigs; Governor Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, a quietly staunch abolitionist; and Judge Edward Bates of the (then) western border state of Missouri. Each man represented a faction of the party whose support Lincoln needed as he tried to avert the break-up of the union. Yet these men’s political differences—not to mention their egos—complicated Lincoln’s task in recruiting all to work on his team. Offering the position of Attorney General, Lincoln had easily persuaded Bates, who warmed to the president-elect’s open, thoughtful discussion of the looming crisis. Lincoln had not yet won over Chase, who thought the position of Secretary of State—which Lincoln had offered to Seward—should go to him. Meanwhile, Lincoln had to carefully manage Seward, who expected not only the top Cabinet position but also a large role in crafting Lincoln’s policies, and who wanted all the other top positions to go to former Whigs like himself.

Indeed, as Lincoln made his way toward Washington, Seward was already trying to disarm the secession movement by pushing in Congress a plan to admit New Mexico to the union as a slave state. Seward, along with Thomas Corwin and Charles Francis Adams in the House, was also recommending passage of a proposed Thirteenth Amendment that seems the very obverse of the amendment passed four years later. The text of the proposed amendment read:

No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.

Anxiety about secession was so great that a resolution to propose this amendment passed the House of Representatives in late February by a two-thirds vote. Goodwin writes that it might have passed in the Senate as well, had opponents not used a procedural maneuver to block a vote on it.

Some historians, pointing to a passage in Lincoln’s first inaugural speech, argue that Lincoln approved the proposed amendment; that it would merely have codified his prior position that, while slavery could and should be kept out of the federal territories, it could not, under the Constitution, be interfered with where it already existed. Perhaps such an amendment would not be inconsistent with Lincoln’s request to Congress, in a special message in March 1862, that it consider a plan for gradual, compensated emancipation of those enslaved. To me it seems improbable that Lincoln really wanted the proposed amendment, or that he would have acknowledged the existence of such a proposal, had it not been urged on him by the many legislators trying to avert disunion. It seems more likely that between his election and the firing of the first shot on Fort Sumter, Lincoln said what he thought necessary to avoid giving more Southern states cause to secede. He refused to signal that he opposed compromise. If and when war came, it would be because the South chose to wage it.

Certainly, during his short stops for speech-making on the train trip to Washington, Lincoln avoided incendiary remarks. He seems to have come closest to stating his real intentions when he disembarked the train to speak at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Under the influence of that hallowed site, Lincoln declared,

I have often pondered over the dangers which were incurred by the men who assembled here and adopted that Declaration of Independence . . . . I have often inquired of myself, what great principle or idea it was that kept this Confederacy so long together. It was not the mere matter of the separation of the colonies from the mother land; but something in that Declaration giving liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time. . . . It was that which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance. . . . This is the sentiment embodied in that Declaration of Independence. . . . If this country cannot be saved without giving up that principle–I was about to say I would rather be assassinated on this spot than to surrender it.

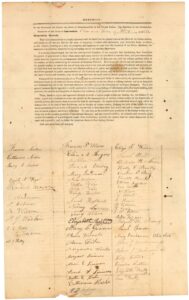

On February 11, however, as Lincoln addressed a crowd of hometown friends gathered to see him off, Lincoln spoke primarily of friendship and gratitude. “No one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything.” Then he spoke of the challenge before him:

I now leave, not knowing when or whether ever I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of that Divine Being who ever attended him, I cannot succeed. With that assistance, I cannot fail. Trusting in Him who can go with me, and remain with you, and be everywhere for good, let us confidently hope that all will yet be well.

Perhaps Lincoln sensed he would never again shake hands with his Springfield friends. He certainly understood his need of their prayers.