Sedition Act of 1798

The presidential contest between an embattled incumbent seeking reelection in a bitterly divided country and his well-known challenger dominated the national spotlight. The hard-fought campaign featured vicious attacks in partisan newspapers. The challenger’s supporters accused the president of authoritarian impulses, bullying his subordinates, trampling constitutional rights, and destroying foreign alliances. The president’s allies fired back. They claimed their opponent was an atheist bent on seizing Bibles from the homes of American Christians, and they whispered tales of animal sacrifices and sexual transgressions by the president’s adversary. The challenger’s supporters anxiously worried that the incumbent would seek to hold on to power even in defeat. The president’s supporters believed the republic’s survival was at stake should their opponent occupy the Executive Mansion.

The Sedition Act of 1798 & the Election of 1800

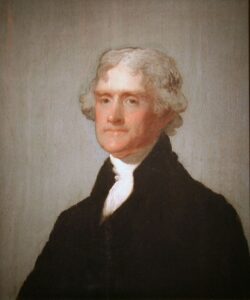

This election was not one of America’s recent campaigns where negative campaigning has become the norm. No, this election occurred in 1800 and featured a struggle between two iconic Founding Fathers, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Adams and Jefferson had been friends during the 1780s and much of the 1790s. However, their relationship began sour when Jefferson served as Adams’s Vice-President (1797-1801) and erupted into open political warfare in the election of 1800. The new nation’s fledgling newspapers served as the frontlines in the contest.

Thomas Jefferson triumphed in 1800, in part, because Adams signed the infamous Sedition Act of 1798. This act made it a crime for anyone to “write, print, utter, or publish … false, scandalous, and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States,” the Congress, or the President. In today’s world, this language is a clear violation of the First Amendment’s protection of freedom of speech and press. At the time, freedom of the press was a tradition still in its infancy in the United States. Therefore, the Act’s Congressional authors saw it as a reasonable and necessary response to the intense partisanship of the of the 1790s, especially the partisan Republican editors that launched scathing attacks on the policies of John Adams.

The Role of the Media

Newspapers in the 1790s were openly partisan. Republican editors published only 16% of the nation’s newspapers in 1795. However, their market share grew to 28% in 1798 and 40% following the enactment of the Sedition Act in 1798. According to historian John Ferling, this “new breed of printers … were driven by ideology and partisanship.” Like partisan cable commentators “owning” the opposition on their nightly broadcasts, these editors “assailed their adversaries” in every type of print available – newspapers, pamphlets, and broadsides.

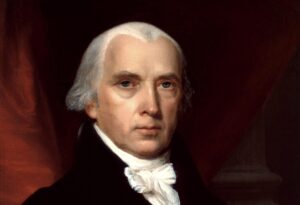

Newspapers did not fire the opening salvo in the partisan struggles of the 1790s. Instead, partisan newspapers arose after competing political parties emerged in the United States, shortly after George Washington took office as the new government’s first executive. One party, coalescing around Alexander Hamilton, became known as the Federalists, and supported President Washington. Thomas Jefferson and his confidant James Madison organized an opposition party, known as the Republicans. As the one man seen as indispensable to the new government’s success, President George Washington was able to moderate partisan conflict while in office. With Washington’s retirement to Mt. Vernon following two terms in office, these groups broke into open political warfare over how best to interpret the Constitution, the federal government’s role, and foreign policy.

Especially thorny were the issues of the potential support for the French Revolution and France’s subsequent war with Great Britain. Republicans backed the French. They reminded the public of France’s military alliance with the U.S. when its Revolution hung in the balance. Federalists argued that Great Britain had a governmental structure the U.S. should emulate and that our shared political, cultural, and commercial ties with England necessitated a strong alliance with her.

In the election of 1800, John Adams was attacked as a closet monarchist who admired the British constitutional monarchy. Adams was accused of wanting a hereditary presidency and a war with revolutionary France. “Readers were reminded that Adams shared responsibility for the … Sedition act,” writes Ferling, and despite the legislation’s expiration date of March 3, 1801, Republicans argued that Adams’s reelection might mean the oppression of the press would continue.

Federalist newspapers were not silent. They accused Jefferson of being an atheist with plans to confiscate Bibles. Although the accusation did not make it into print until three years later, rumors circulated that Jefferson had engaged in a sexual relationship with an enslaved woman on his Monticello plantation named Sally Hemmings.

The Sedition Act of 1798 was not the only factor contributing to Adams’s defeat. Americans were angry about high taxes, Jay’s Treaty – which seemed too favorable to Great Britain – and a Quasi-War with France they feared would erupt into full conflict at a time the new republic could ill afford a war. Still, the Sedition Act had a significant impact. Over two dozen editors – most of them Republican-leaning – were arrested and charged with publishing seditious content. Perhaps the most prominent of those arrested was James Callender, whose anti-Federalist tract, The Prospect Before Us, Jefferson backed financially. Convicted under the Sedition Act, Callender was ordered to pay a $200 fine and sentenced to nine months in prison.

Another victim of the Adams administration’s attempt to silence its opponents was Congressman Matthew Lyon of Vermont. Lyon attacked President Adams in print and in speeches, accusing him of having “an unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation and selfish avarice.” Lyon was also arrested, convicted, and sent to prison under the Sedition Act – but the Vermonter enjoyed the last laugh. He secured his reelection to the House of Representatives while serving his prison sentence.

Responses to the Sedition Act of 1798: The Virginia & Kentucky Resolutions

Arguably, more important to the nation’s history than the trials and convictions of Matthew Lyon and James Callender was the response to the Sedition Act by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Each of these future presidents took up their pens and authored – anonymously – resolutions of protest and forwarded them to the state legislatures of Kentucky and Virginia, respectively. Jefferson composed a detailed legal argument challenging Congress’s constitutional authority to pass such legislation. Interpreting the Constitution narrowly, Jefferson argued that sedition was not a crime that Congress had authority to prohibit, that the Sedition Act specifically violated the First Amendment’s freedom of the press and speech, and that under compact theory, the states were the last resort for determining the constitutionality of Congressional legislation.

The Virginia Resolutions, drafted by James Madison, also cited compact theory as justification for state protests against the Sedition Act. The federal government was a “compact to which all states were parties,” argued Madison. States were “duty bound, to interpose” and block implementation of federal statutes that assumed powers not explicitly delegated to the national government under the compact.

For students, the Sedition Act of 1798 and the Republican response to the act provide numerous opportunities to explore major themes in American history and government. There are the similarities between the intense partisanship of the 1790s and today’s partisan environment that students could analyze. Teachers may wish to have students examine the concept of Judicial Review by comparing Hamilton’s argument in Federalist 78, Chief Justice John Marshall’s majority opinion in Marbury v Madison (1803), and Jefferson and Madison’s contentions in the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. Compact theory reappears in American history throughout the antebellum era. Two examples are the nullification crisis of 1832 and the secession winter of 1860-61. Teachers might ask their students to discuss whether the compact theory articulated by Jefferson and Madison differed from that of John C. Calhoun in the Nullification Crisis or the secessionists’ conventions on the eve of Civil War.

Civics and government teachers may use the Sedition Act of 1798 to study the limits of free speech in America. The Supreme Court decision in Barron v Baltimore (1833), in which the Court ruled that the Bill of Rights did not apply to the states, could be contrasted with the conception of incorporation under the 14th amendment through which the Court has later ruled that most of the Bill of Rights does apply to the states.

As I write this, I get excited just thinking of all the good questions to ask students. How does the context of the passage of the Sedition Act of 1798 compare to that of 1917, when efforts were also made to restrict First Amendment rights? What are the limits of free speech? Would you agree with the Supreme Court’s ruling in – for example – Snyder v Phelps (2011), Tinker v Des Moines (1969), or Schenk v U.S. (1919)? What provocative questions can you think of?

To learn more about the political battles of the 1790s and their culmination in the election of 1800, please see the latest addition to our bookstore, From Bullets to Ballots: The Election of 1800 and the First Peaceful Transfer of Political Power.