Separation of Powers: An Interview with the David Alvis and Joe Postell

We’ve released a new document collection that addresses a complex issue in American constitutional government, Separation of Powers. As the editors, J. David Alvis and Joseph Postell, observe in the introduction to the volume, “The separation of powers in the US Constitution takes minutes to learn and a lifetime to master.” To the founders, prevention of tyranny required separating the powers into different branches; yet defining “with certainty which powers belong to which branches” posed questions that continue to perplex us today. We explore these challenges in the interview that follows.

David Alvis teaches Political Science at Wofford College. With co-authors Jeremy Bailey and Flagg Taylor, he published a book exploring one of these challenges, The Contested Removal Power, 1789 – 2010 (Kansas University Press). Joseph Postell teaches Politics at Hillsdale College. His recent publications include Bureaucracy in America: The Administrative State’s Challenge to Constitutional Government (University of Missouri Press, 2017)). Both Alvis and Postell teach in TAH’s Master of Arts in American History and Government program.

The founders thought that liberty could be protected only if the powers of government were divided into distinct branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. But what they actually gave us is a system of blended powers. Why did they do that?

Alvis: In other words, why did they mess it up? As Madison said in Federalist 47, the accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive and judicial, in single hands is the very definition of tyranny. Seems like that’s something you don’t want to get wrong. You’d want to be something of a purist about that. This is actually one of the charges that the Antifederalists make about the proposed Constitution—that in blending the powers, it violates a basic premise of republican government. Looking at the Constitution, you see numerous instances of this.

One of the strangest is that the president, in order to hire any of the principal executive officers, has to seek the approval of the Senate. Isn’t that comparable to the CEO of a company asking the approval of a rival company before hiring a particular employee? Why would you do that?

Well, each branch needs a way of checking the others. You’ve got to grant each branch a small measure of the others’ powers so that, when any branch feels its domain is intruded upon, they have the means to fight back. That’s why the president has to seek the advice and consent of the Senate before appointing a principal officer.

The Constitution provided these checks, yet sometimes the intervention by one branch in another’s business causes problems. Balancing the powers between the branches is always a work in progress.

Postell: The founders had to figure out how to make the separation of powers to work in practice, rather than in theory. If you don’t give some of the powers of one branch to another, then you haven’t provided the means of checking encroachments by one branch on another. If the Senate doesn’t have the power that David just discussed, then the Senate doesn’t have a check on the executive. If the executive doesn’t have a veto power, then the executive doesn’t have a check on the legislature.

In theory—and this is what the Antifederalists argued should happen in practice—a republican government should be able to follow the procedure described in the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. It says, we’re assigning all the legislative power to this group, all the executive power to another, all the judicial power to a third party—and they all need to stay in their proper spheres. But that arrangement sets up what Madison, In Federalist 48, calls “parchment barriers.” If power is of an encroaching nature, you need something stronger than a rule written on paper to restrain it. So, you blend the powers.

A real problem remains, however. Although Madison and Hamilton do not want to talk about this much, Madison admits in Federalist 37 that it is really hard to figure out where some of the powers go. Take the war power. Is that an executive power? Or a legislative power? What about the treaty power? According to the Constitution, the Senate ratifies treaties, but the president negotiates them. Still, sometimes senators try to write treaties, which obviously presents practical difficulties.

This is a basic question about legislative power. What is a law, and what is an execution of law? Today, this may be the most significant issue in the separation of powers. As Madison says, we’ve never been able to clearly delineate those two functions. That’s another reason why, in our Constitution, the powers are blended.

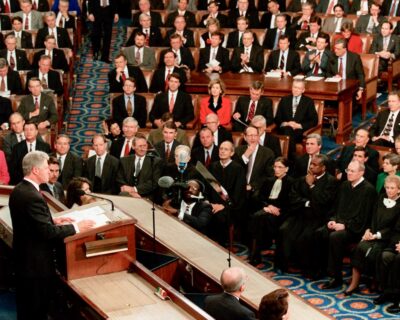

Do most Americans understand the separation of powers? Often, when Supreme Court decisions are announced, one group loudly celebrates and another group mourns, as if their liberties have ended. Do such reactions show that citizens accept the Court’s authority?

Postell: I don’t know if the people really do understand the separation of powers. They respect the finality of a judicial decision, but often they’re confused about what that decision is: that it is not a political decision; it is a constitutional ruling on a constitutional question. Most Americans respect the way the Constitution separates the powers, but they don’t really understand the concept of separation of powers. I’m interested in what David thinks about this.

Alvis: I think public opinion today is very much informed by the early 20th century progressive critique of the Constitution. To the Progressives, the concept of separated powers was at odds with democracy. Democracy should allow the almost immediate enactment of majority will, but the separation of powers was designed to thwart that—to shackle government and make it as ineffective as possible. Progressives sought a way around the separation of powers so as to fulfill democratic ends. Today, many citizens share that view; they complain that politics is inefficient.

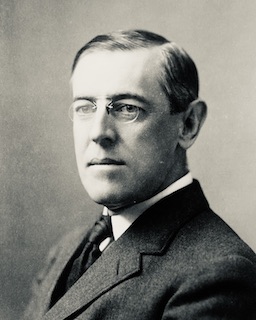

Our collection includes a selection from Woodrow Wilson. He argued that democracy can work only if you have one individual you can hold accountable, who can deliver on popular will with maximum discretionary authority. This has become the expectation of American citizens, so they often are disappointed with their presidents. When presidents try to explain how the separation of powers limits what they can do, people see them as making poor excuses. The public knows we have a system of separated powers. But as Joe pointed out, they’re not really clear on why.

To speak of the popular will as obvious and demanding fulfillment—doesn’t that ignore the views of the minority?

Postell: Well, Wilson and the other Progressives saw the popular will as unitary. The notion that you could have a plurality of popular wills, that the Senate could represent a certain kind of popular will, that the House could represent a different kind of popular will, and the president a third kind–that just wasn’t something that the Progressives had room for in their political thought. They saw the nation as an organic whole with a single will represented by a single person—the president. There’s a single majority with a single goal, and therefore you have to consolidate power to get things done. The framers saw a plurality and diversity of opinions, so they created a diversity of institutions to express those opinions. Today, the public sees the framers’ plan as clunky and gridlocked.

It’s true that many citizens expect the executive branch to wield the greatest power. Teachers tell me their students think the president can do anything. Do you hear the same from the undergraduates you teach?

Alvis: Yeah—I hear that from presidents as well!

Postell: You’d expect me to say, “I’m at Hillsdale College, so I don’t hear that.” Actually, students who lean conservative think the same thing. It’s fascinating to hear them assess presidents. Take Ronald Reagan: students on my campus speak of him as if he were the sole actor in the government of the 1980s, that he wasn’t dealing with a Democratic Congress and didn’t have to negotiate with House Speaker Tip O’Neill. Even people who take the Constitution very seriously still lean very much towards presidentialism in the way they think about our history. We define eras by presidents, right? We don’t speak of the era of the O’Neill speakership.

Yet the founders expected the legislative branch to be the strongest. Why haven’t things worked out that way?

Postell: It’s in Federalist 48 that Madison makes the claim that the legislature is an “impetuous vortex” and therefore the most dangerous branch. His reasoning is persuasive. He says that citizens will more easily attach themselves to their representatives than to the president. When I teach this to my students, I ask them to think about what life was like in 1787. They immediately see it: people in that time had no radio or television, so they might never see the president or hear him speak. Yet they were likely to see and hear their representatives. In the beginning, there was one representative for every 60,000 citizens. So much has changed since then to upset that balance. [Editor’s note: Today there is one representative for every 747,000 Americans.]

Alvis: I do think that modern communication has given the president a much stronger voice and a much heavier hand over Congress. But I differ from Joe here. I also have to differ from Madison! When Madison says in Federalist 48 that the legislative branch will always predominate, that’s primarily because Madison sees the legislature as the real manifestation of majority will. I just don’t think that’s true. In the early republic, there was a prejudice in favor of the legislative branch, primarily because people identified the governor’s office with the crown. They preferred their legislative assemblies. This prejudice did not necessarily mean that the legislative branch best articulated what the majority will was. Numerous fractious constituencies elected the legislative branch. But the president had a national constituency.

I think the framers understood this. The President would take a primary role in setting the legislative agenda precisely because the president represented that national opinion. That’s why, in Article II, the president is given the responsibility of making legislative recommendations. And from the very beginning, presidents really did set the legislative agenda. Look at the first Congress. They mostly abandoned their legislative role and just gave Alexander Hamilton carte blanche authority to write legislation! In some ways, it makes sense for the executive to articulate the priorities. But the details of those policies need to be worked out in the give and take among Congressional constituencies.

Does this new imbalance have anything to do with Congressional tenure in office?

Today, that’s become more complicated, primarily because the media has shifted the balance so far to the executive. Also, Congressmen have often neglected their responsibilities. They write statutes that are enormously vague, and give the executive free rein to fill in the details. Recently the Court has pushed back against this imbalance. A case decided this summer, Biden v. Nebraska, involved the partial student loan forgiveness program, which was done by executive order. The Court said the order went well beyond the statutory authority of the executive.

Alvis: It helps their reelection prospects if Congressmen don’t have to take accountability for writing the statutory law. They don’t have to deal with the backlash when a law has unintended consequences. Also, today, Congress can claim that the details of legislation are well beyond their ability to decide. The regulatory, economic and technological issues exceed the expertise of any member of Congress. That conveniently dovetails with the advantage of avoiding accountability.

Postell: It’s true that we see a correlation between Congress’s delegation of authority to the president and overall tenure in office. But there’s another way of looking at this that may better capture what’s going on. There are two ways to delegate power. In the last century, we’ve seen both. The first is to just abdicate: write a really broad statute, call it a day, and let the bureaucracy take it from there. That’s where we are today and, I’d say, where we’ve been probably for the last 30 years. But for most of the 20th century, Congress delegated in another way. John Dingell, Robert Byrd, Orrin Hatch—these very distinguished members of the 20th century Congress were adept at delegating power while controlling its exercise afterwards. They did this through what Madison, in Federalist 48, called the power of the purse. They used their appropriations to control the funding of agencies, and in doing so they made the agencies more accountable to them than to the President. In fact, by delegating to the bureaucracy, they increased the bureaucracies’ accountability to them.

If you want to pass a law, you need a majority of the votes in Congress. But if you delegate the power to the Department of Health and Human Services, and then you’re on the committee that oversees the appropriation to HHS, you can single-handedly accomplish a lot more than you could if you tried to pass a bill. Your committee can influence the bureaucracy in a particular direction. The classic example is John Dingell as the chair of Energy and Commerce in the House of Representatives. He was from Detroit. He wanted to make sure that anything that affected the auto industry was not going to hurt his constituents. His chairmanship allowed him to control much of the administrative state’s rulemaking on such things as energy and the environment. In this way, Congressional leaders gain power over policy—but they do so individually rather than collectively. We used to call this the “iron triangles” of interest groups, Congressional committees and the bureaucracy, who together would craft policy without really submitting it to evaluation by the “national will.” For 50 years, legislative decision-making worked this way. Then, over the last 40 years, the whole system of interest groups and committees fell apart, leaving us with polarization and partisanship.

You mentioned the power to make war or peace. This seems very hard to sort out. The country needs a single guiding hand to prevent confusion and disaster in times of war. Yet a president with tyrannical tendencies might carry the nation into an unnecessary war, or make a dangerous alliance. How did the founders sort out this problem?

Alvis: We do tend to think of the foreign affairs power as vested in the executive, because the president always seems to be front and center when it comes to foreign affairs and defense crises. Prior to the American founding, political theorists almost always argued that the foreign affairs power should be entirely controlled by the executive. War and foreign affairs demand “decision, activity, secrecy and dispatch,” Hamilton said. As John Locke argued, in the international realm, countries exist in something like a state of nature. It’s a matter of survival. You must vest responsibility for foreign relations entirely in the executive, who wields power over war and peace with an absolute prerogative.

But the Constitution distributes this power between Congress and the president. The president is commander in chief, but Article I, Section 8 gives Congress many powers over the military and its use—most importantly, the power of the purse; and “money is the sinews of war,” as Cicero said. So, Congress makes rules and regulations for the military branches. It also fixes the standards for naturalization.

In departing from prior political thinkers, the founders seem to have had two aims. First, they wanted to structure deliberations about war and peace so the branches would have to fight them out. Indeed, during the past century, there have been a lot of arguments between Congress and the president over foreign affairs. The founders accepted that tension in order to hold the foreign affairs power accountable to law.

Second, the founders distributed this power in a way that corresponds logically to the different kinds of decisions a country needs to make with regard to foreign affairs. To negotiate a treaty, you can’t involve 535 people. One person must manage the negotiations, but the entire Senate might usefully lend its advice and consent to it.

Do you agree, Joe?

Postell: Yes—except that this balance that David has just talked about no longer seems to hold. Many of the documents in our collection show that during the last half century power over foreign affairs has shifted toward the executive. We don’t declare war anymore. Presidents can use their large defense budgets to commit troops overseas. Once the troops are put in harm’s way, Congress’s hands are effectively tied. If they withdraw funds, or use the appropriations riders to force the troops out, they are seen as abandoning those who fight for us. The War Powers Resolution was an attempt to limit presidents’ ability to commit troops to conflict zones, but it has not proven effective.

Also, the treaty power has been essentially rendered obsolete by so-called “executive agreements.” The president concludes an agreement with another country without calling it a treaty, and therefore doesn’t have to submit it to the Senate for ratification. The framers were very careful to distribute the foreign affairs power between the executive and legislative branches. But during the last few decades of the 20th century, we departed from the balance they struck.

Would you give an example of the executive agreements you’re describing?

Alvis: The Iran nuclear deal made at the conclusion of the Obama administration was an executive agreement.

Postell: Right. Had it been a treaty, it obviously would not have received the two-thirds vote in the Senate needed for ratification. The Iran deal was very much a talking point among Republicans of the time, who objected to the president making such an agreement without going through the treaty process.

Alvis: Of course, there are repercussions for presidents who use these executive agreements. Presidents want to achieve a lasting policy legacy, and foreign negotiations entail large investments of their time. You see the benefits in the long term, not in the short term. But an executive agreement lasts only as long as the next president agrees to it.

As Obama worked on the Iran deal, he vowed to design it in a way that would prevent another president from immediately undoing it. Well, almost within six months of Trump’s election, he had us out of the Iran nuclear agreement.

Postell: We should note that presidents have engaged in undeclared hostilities abroad from the time of the early republic. Jefferson famously waged a small war with the Barbary pirates. He did not declare war—he just sent in the Marines; but he did conclude a treaty with the Bey of Tripoli. In other cases, presidents concluded executive agreements with foreign powers. My students in Michigan are fascinated to learn that Monroe made an agreement with Canada regarding naval armaments on the Great Lakes. He did it without submitting it to the Senate. Although some argue that it’s unconstitutional for presidents to unilaterally commit forces abroad or make executive agreements with foreign powers, it’s actually much more ambiguous. What’s changed in recent decades is the scope of such conflicts and the length of the commitment. The Vietnam War exceeds in both scope and duration such episodes as Jefferson’s naval war with the Barbary pirates.

Your dialogue is fascinating. As you put the collection together, did you debate many of these issues?

Alvis: On a daily basis! We debated as we selected documents for inclusion in the book and as we wrote the introduction. It was a great collaboration. You can tell I’m a little more executive centered; Joe is much more legislatively centered. We both admire the founders’ design for separated powers, yet each of us strikes his own tone. I think our different perspectives really benefit the collection. Each suggested documents the other had not thought of. Joe really has done an enormous amount of work on Congress; he knows the literature thoroughly. My presidential perspective is more typical in this discussion.

Postell: Of course, much of the book really just traces the trajectory of these questions over time. This made it easy to reach consensus, because it’s easy to see how these things have developed.

Of all the documents in this collection, which do you regard as indispensable? If your students have time to read only one or two of the selections, which should you assign?

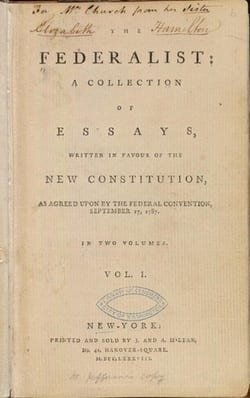

Postell: One cannot omit The Federalist. In our collection we grouped excerpts from 47, 48 and 51. The arguments in those essays are still highly relevant. Even if you consider some of the analysis in them questionable, they set the terms of the debate that follows. Take Federalist 51. Madison says that because so much power will accrue to the legislature, we need to break it into two houses, elected in different ways. Bicameralism will allow the House and the Senate to check each other. Imagine if the founders had not made that choice. How differently would the debates between Congress and the president be conducted! Congress would probably be much more powerful today if it weren’t for its bicameral structure. For that reason, I think The Federalist is still the best place to start.

Alvis: I agree; but if you’re going to teach Federalist 51, which makes the case for checks and balances so eloquently, you should also assign Centinel I. It challenges the whole concept of checks and balances. “Centinel” was Samuel Bryan, a Pennsylvanian. His state’s constitution was the butt of every joke. It provided for a unicameral legislature and almost no checks and balances—the worst design possible! But Centinel essentially says, “Your complex system of checks and balances only works because of people’s vices. You assume the three branches will continually fight each other for power. Rivalry—not some shared sense of the common good—will keep each branch in its proper sphere. It’s a government designed by geniuses that’s meant to be run by idiots. But that’s not why we Pennsylvanians chose to live in a democracy! We chose democracy because we believe in the virtue of our citizens. We meant to design an unsophisticated constitution, one of pure democracy in action.”

Reading Centinel alongside Federalist 51 forces you to think, are checks and balances really necessary? If so, why? Is it because we’re failing at the task of civic education? Or is it because as human beings, we’re never going to grow out of our vices? In any case, our debate on the separation of powers will likely go on forever, because problems continually arise, and we must continually adjust the balance.

David Alvis is Associate Professor of Political Science at Wofford College. He received his Ph.D. from Fordham University in New York in Political Science and his master’s in American Studies from the University of Dallas. At Wofford, he teaches courses on American Politics including: The American Presidency, Constitutional Law, and Political Parties.His publications include articles on the Electoral College, the Presidency, Progressivism and early twentieth century politics, the Obama Presidency, and the films of John Ford.

Joseph Postell is Associate Professor of Politics at Hillsdale College, where he teaches courses on American politics, Congress, Political Parties, and administrative law. His research focuses primarily on American political institutions and their relationship to the modern administrative state.

Professor Postell is an alumnus of Ashland University, where he was an Ashbrook Scholar.