September 25, 1789: Congress Proposes a Bill of Rights

On September 25, 1789, the first Congress of the United States agreed on a set of twelve amendments to be submitted to the states for ratification. These proposed amendments grew out of a debate that arose during the closing days of the Constitutional Convention, two years prior. Professor Gordon Lloyd’s Core Document Collection, The Bill of Rights, and his online exhibit on the Bill of Rights, chronicle this story.

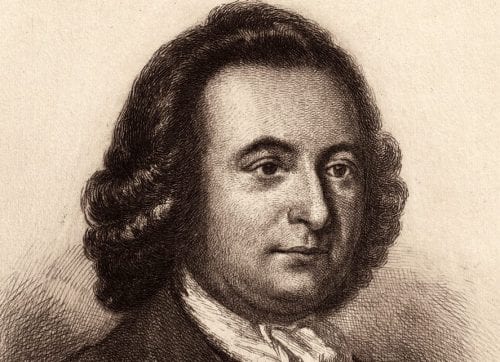

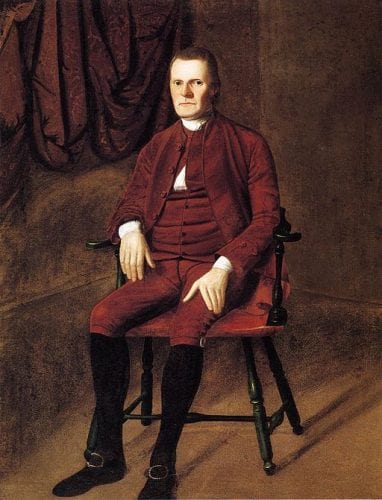

Three delegates who had sat through the entire convention, participating in all the deliberations that led to the draft completed in September 1787, now balked at signing the document. Two of them—George Mason of Virginia and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts—objected to the absence of “a declaration of rights.” Returning home after the convention, Mason listed his objections. Many were quibbles with the powers granted to the House, the Senate, and the president. The Constitution’s signers had opposed any late alterations of enumerated powers; these would unravel the just negotiated, carefully knit frame of government. But Mason’s objection that “there is no declaration of any kind, for preserving the liberty of the press, or the trial by jury in civil causes; nor against the danger of standing armies in time of peace” was harder to ignore.

Some proponents of the Constitution—notably James Wilson of Pennsylvania—had argued during the convention and during the later ratifying debate that the people were adequately protected by the declarations of rights that prefaced many of the state Constitutions. This argument did not reassure Mason, who himself was principal author of the Virginia Declaration of Rights. During the last days of the convention in Philadelphia, he had pointed out that “the laws of the general government being paramount to the laws and constitutions of the several states, the declarations of rights, in the separate states, are no security.”

The State Ratifying Conventions Call for Amendments Securing Rights

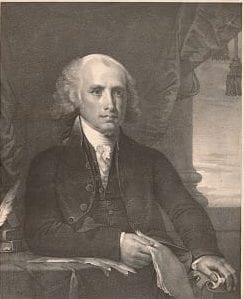

Such concerns arose again at many of the state ratifying conventions. This caused James Madison, who was then collaborating with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in a series of editorials explaining and defending the Constitution (later compiled and published as The Federalist), to reconsider his reluctance to amend it. During an exchange of letters with his friend Thomas Jefferson (who was serving as Ambassador to France), Madison grew convinced a declaration of rights was needed.

The argument “ratify now, amend later” persuaded skeptical delegates at the ratifying convention in Massachusetts to approve the Constitution. New Hampshire, Virginia and New York then followed suit, making the Constitution the nation’s framework of government and allowing a new federal government to form. However, two of the thirteen states—North Carolina and Rhode Island—still declined to ratify at the time the First Congress met, on March 4, 1789.

In June, Madison argued that amendments securing rights be inserted within the existing text of the Constitution. Congress studied and debated Madison’s proposed 17 changes that summer. During the House debate on Madison’s proposals, Roger Sherman of Connecticut persuaded his colleagues that any amendments to the Constitution should be added as addenda, not incorporated into the original document that the people had approved in the state ratifying conventions. “The Constitution is the act of the people, and ought to remain entire. But the amendments will be the act of the state governments,” Sherman pointed out. (According to the procedure specified in Article 5 of the Constitution, proposals for amendments that originate in Congress must be approved in the state legislatures.) The Senate debate narrowed Madison’s proposals down to 12.

Reluctant States Finally Ratify the Constitution

Congress’s action motivated the reluctant states to finally ratify the Constitution, as one can trace on this timeline. North Carolina called a new convention and ratified the Constitution in November 1789. It adopted the proposed amendments one month later, the second state (after New Jersey) to do so. Rhode Island, which had not yet called a ratifying convention, did so in early 1790. In May 1790 it was the last of the thirteen states to ratify the Constitution; two weeks later it was the eighth state to adopt the Bill of Rights.

The Bill of Rights became part of the Constitution on December 15, 1791, the same day that Virginia ratified ten of the amendments Congress had proposed. What about the other two amendments? They pertained to the structure of Congress—not, directly at least, to individual rights or states’ rights. Yet the second of those amendments, which prohibited a sitting Congress from giving itself a salary raise (stipulating that any such raise would take effect only after a new election), did eventually become part of the Constitution. It was adopted as the 27th amendment in 1992.