The Four Eras of Congress’ Evolution—and Devolution

Professor Joseph Postell has edited a new volume in our Core Document Collection, Congress. The collection documents dramatic changes in Congress’ role and function as successive generations of leadership shaped the institution’s rules and procedures. Postell, whose research interests include Congress, political parties and the administrative state, is the author of Bureaucracy in America: The Administrative State’s Challenge to Constitutional Government (Studies in Constitutional Democracy, University of Missouri, 2017) and a co-author of books on American conservatism and political economy. Formerly Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, this fall he assumes a new teaching position in the Politics Department of Hillsdale College. Recently we asked Postell to explain how Congress has developed since the founders drew its original design.

What were your aims as you selected documents for the volume on Congress?

I wanted to tell the story of Congress historically. No undergraduate-level textbook on Congress describes its historical development. Yet we seem to study the Presidency only historically, perhaps because the presidency changes dramatically and in one direction. It begins as a limited, restrained institution; then executive power expands massively in the 20th century, thanks to Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Congress changes, but not in a single clear direction.

Also, Congress is much more complicated than the Presidency. To understand it, you must study the rules committee, the committee assignment process, and legislative procedure. That’s as the founders intended. They wanted the presidency to be simple and unified, so that when emergencies arose, it could act energetically; but they wanted Congress to reflect the complexity of a self-governing people.

I argue that Congress has evolved through four eras, operating during each in a different way. In the beginning, Congress was small and disorganized. There were no committees and no party leadership. Members debated, took votes, then hung out in the mess together. In one of the primary sources for this period, Congress is described as “babble town.”

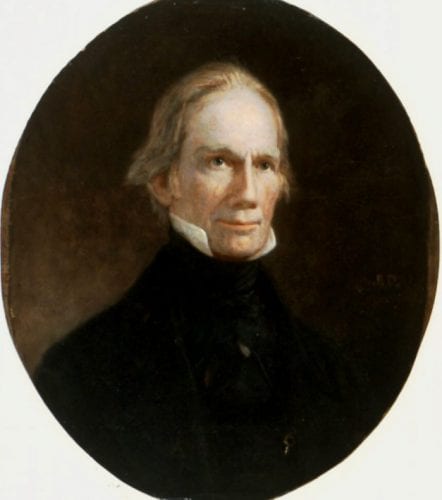

The Constitution does not prescribe leadership for Congress. It provides for a speaker of the House, but doesn’t say what the speaker will do. Madison, in Federalist 55, admits the problem when he writes, “Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.” As the nation grew, Congress would become unwieldy unless some internal structure developed to steer action on behalf of the majority. Henry Clay, amazingly elected Speaker of the House on the first day of his first term in office, offered a solution. He introduced rules. Prior to Clay, you could filibuster in the House just as much as you still can in the Senate. John Randolph of Roanoke, a strident and uncompromising representative, filibustered everything and paralyzed action. Clay introduced the “previous question motion” in 1811: he interrupted Randolph, moving that the question before the House be submitted to a vote. When the majority approved the motion, a vote occurred and a new procedural rule was born.

As the 19th century continued, Congress gradually became more organized. Clay did not achieve all he wanted. As a Senator, he tried to get the cloture rule he’d secured thirty years before in the House. John Calhoun and Thomas Hart Benton were filibustering to prevent renewal of the National Bank charter. Clay argued that the people expected Congress to act; Calhoun and Benton protested, “This is a deliberative assembly; you cannot cut off debate!” Clay didn’t get cloture, although to avoid the rule change, his opponents allowed the Bank to be rechartered.

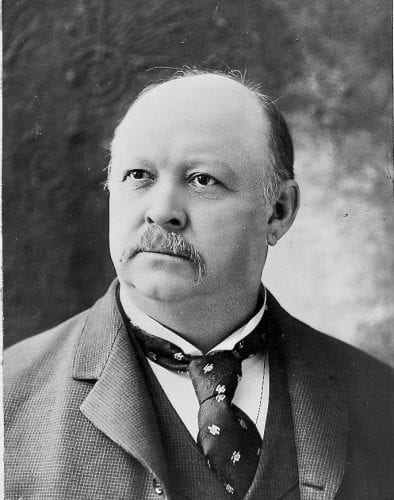

Clay pushed a national vision for the country. He understood that, like the president, he was indirectly elected by the whole nation. But it was the great speakers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries – Thomas Brackett Reed and Joseph Cannon – who understood that collective action on behalf of the nation required party organization. The parties became powerful machines, and their “czars” the leaders in Congress. In the 1870s and 1880s, the Speaker emerged as a powerful centralizing force to discipline Congressional committees. We see the perfection of this second era of Congress between 1890 and 1910. Political scientists call this the “institutionalized Congress.” It was centralized and party-driven.

Before you go further, would you talk about a word Calhoun and Benton used—their insistence on deliberation? The word suggests joint reasoning, or a process in which Congressmen and Senators refine their ideas and work out compromises through debate. Does this accurately describe the work of Congress?

That’s a difficult question. In the language of Federalist 10, legislative debate should “refine and enlarge the public views.” We will elect the best among us, and they will reason together about whether we should declare neutrality or go to war with Great Britain. Yet this expectation alarmed the Antifederalists. They feared that Congress would become an elite body out of touch with those they represented – a “Washington establishment.” Publius responded that representatives who only reflected constituents’ opinions would not unite to carry out the nation’s business. Rather than taxing their constituents, they’d default on the nation’s debts, as they had under the Articles of Confederation.

Still, even the Federalists agreed that representatives should be advocates for their districts. Advocates don’t deliberate; they contest. Eventually, advocates for different constituencies will bargain and reach compromise—that is the real argument of Federalist 10. But bargaining differs from the more speculative debate of the Constitutional Convention, in which delegates considered a range of proposals before agreeing on a plan for the wellbeing of the whole. In a way, the founders expected Congress to do two incompatible things.

Speaking of the argument of Federalist 10: does it still apply? Madison argued majority factions would not arise, since each congressional district would have a single dominating interest that competed with the multiplicity of interests in other districts. Since Madison’s day, haven’t improved transportation and communications homogenized interests across broad regions?

To a limited extent, Madison’s argument still applies. Decisions about agricultural incentives and military base closures still arouse representatives’ parochial concerns. Although divided on ideological grounds, members will always think of their own constituents’ livelihoods. There are great examples of conservative, anti-subsidy congressmen getting voted out by their conservative, anti-subsidy constituents for voting against soybean supports.

You remember Tip O’Neill’s famous aphorism that “All politics is local”? Well, in the third era of Congress, committees dominated the legislative agenda, allowing members to protect their districts’ interests.

The third era began abruptly with a 1910 debate—by far the longest document in the collection—over whether the Speaker should be stripped of his powers. On St. Patrick’s Day in 1910, while all of Joseph Cannon’s supporters were out drinking and partying, a quorum of members in the House took this action, before Cannon’s supporters got back in to vote.

After that, Congressional committees were not disciplined by leadership. Power was dispersed among committee chairs, who allowed district interests to take over various policy areas. Meanwhile, executive agencies worked with these committees to administer policies on behalf of these interests. Compared to the theory of Federalist 10, you do have a multiplicity of interests, but they do not contest each other. As long as everyone got on their favorite committee—agriculture, natural resources, banking and finance, public works—every interest was taken care of. Political scientists refer to “the iron triangle” of the committee chair, the agency, and the interest group who together determine federal policy. National issues are not even part of a member’s calculation.

As a consequence, reelection rates go through the roof, seniority and tenure in Congress go way up, and the parties are less ideologically distinct than before. A kind of bipartisan system arises, with liberals and conservatives in each party.

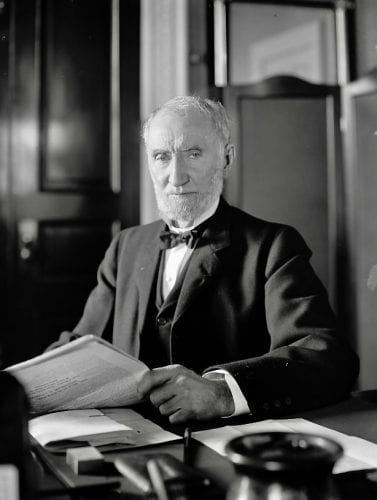

Some political scientists call this the “textbook Congress.” (I think it’s the antithesis of what Congress should be, but political scientists tend to think committees should be part of any functioning legislature.) In this limited way, the kind of Congress Madison envisions in Federalist 10, an interest-based one, does prevail for 60 years or so. Progressive Democrats hate this system, because the seniority rule gives conservative Democrats control over all the committees. They are constantly trying to push broader national interests—the Great Society, environmental issues, equal employment, civil rights, fair housing. You can’t pursue such big sweeping reforms at the committee level; you need buy-in from across Congress. In the document reader, the debate over the 21-day rule (a very arcane procedural mechanism to bypass committees), shows one of Sam Rayburn’s attempts to pass such national reforms. Eventually, he gained the power to pack the rules committee so that he could get some measures passed.

The question you’re raising—whether communications and technology have reduced the differences among all these interests—became pertinent in the fourth era of Congress. Starting in the 1970s, partisanship swept over the institution. The interests don’t seem to be geographically sorted anymore; if you are a Republican in Oregon, you kind of think the same thing as a Republican in Michigan or in Florida. In other regions, interest and ideology merge, producing mostly Democrats in Massachusetts or Republicans in Oklahoma.

You might think the fourth era an improvement—members are no longer preoccupied by narrow interests. Yet Congress becomes a polarized institution where there is no deliberation and very little compromise. The committee system no longer functions. It’s hard to amend bills. The last few documents in the reader show the reaction against a Congress that no longer does the work it used to do.

Today, do interests vary less by region and more by status and income? Many industries do not employ as many workers as before. While a congressmen’s district may have a major industry, most of his constituents may work in retail or service jobs.

When the economy becomes nationalized and even globalized, congressmen have little motive to represent the big interest in their districts. Amazon doesn’t care if you don’t represent its interests; it’s so big it can just pick up and leave. Also, with new media technology, campaign funding now comes from outside the district. Why should a member worry about his constituents, when the corporate headquarters financing his campaign, and the lobbyists and consultants, are elsewhere? What’s the point of running a local, grassroots campaign when you can run as a national candidate and use your office as a platform to a higher one?

Yuval Levin writes that today’s Congress is more performative than legislative (A Time to Build, Basic Books, 2020). Once, if you went to the Senate, you stayed there and helped build the institution. You mastered Senate rules and norms, you carefully studied your committee’s work, and you served there for 20 or 30 years. Now you use the office to run for president, or sell books, or give paid speeches.

Jeremy Bailey, who edited our collection on the presidency, notes that Congress has ceded many of its Constitutionally granted powers to the executive. Instead of legislating to impose or remove tariffs, for example, Congressmen find it easier to win reelection if they leave controversial decisions to the executive, then criticize decisions that have bad outcomes.

Today’s Congressman claims an ideology but does nothing about it. He goes on cable news or his YouTube channel or Twitter to make a statement about what the president did. But he doesn’t introduce a bill to reverse the president’s action—or even to endorse it. He just wants to make a speech. Madison never really envisioned a Congress that would be the opposite of “an impetuous vortex,” that, instead of taking the powers of the other branches, would expel its own powers.

Reluctance to legislate began in the third era, when Congressional committees collaborated with executive agencies. Then, Congress had it both ways. It disclaimed responsibility for decisions while making sure that decisions were made in the right way for constituents. It gave power to the bureaucracy, yet influenced policy on the back end, where nobody’s watching.

Today’s Congress has abdicated responsibility for the bureaucracy. The old Senators—the Robert Byrds who stayed in Congress for 30 years—made the bureaucracy fear them. When they summoned officials to committee hearings, they showed they knew just as much as the bureaucrats did, because they’d been studying policy for just as long. Now the bureaucrats know a lot more than Congress.

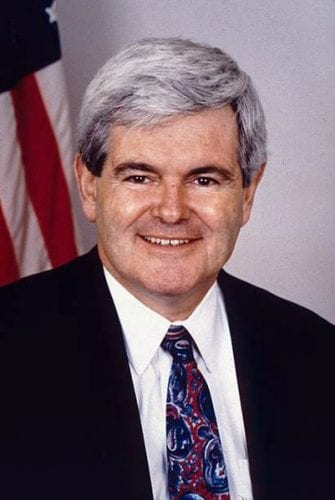

Democrats began weakening committees in 1974, after Watergate. Republicans went further in 1994, when Newt Gingrich tried to nationalize the elections through the “Contract With America.” Tom Delay, Majority Leader under Speaker Gingrich, admitted that this meant taking on the committees. They set limits on how long you could chair a committee; they bypassed the committee process to bring forward legislation written by task forces; and they dramatically slashed funding for committee staff. It seemed a return to the second, speaker and party-dominated era. But they drained Congress of policy expertise, and, in reducing institutional allegiance to committees, they reduced allegiance to the institution of Congress itself. Today, the speaker leads Congress but cannot count on loyalty. Speakers Boehner and Ryan could not drive the agenda, and Speaker Pelosi contends with challenges from first-term congresswomen like Ocasio Cortez.

If you don’t have institutionalists, you don’t have an institution. Separation of powers is predicated on the idea that “ambition must be made to counter ambition,” with the interests of the official tied to the constitutional rights of the body where they serve. We’ve destroyed that connection. Some people declare Congress obsolete. Compared to the presidency, it’s ineffectual.

Yet we did not have to end up here. Studying the history of Congress shows us alternatives to the present moment. If we lose Congress, we lose the one thing American constitutionalism has contributed to western civilization: government by elected representatives. This alone allows a workable government based on republican principles.