Introduction

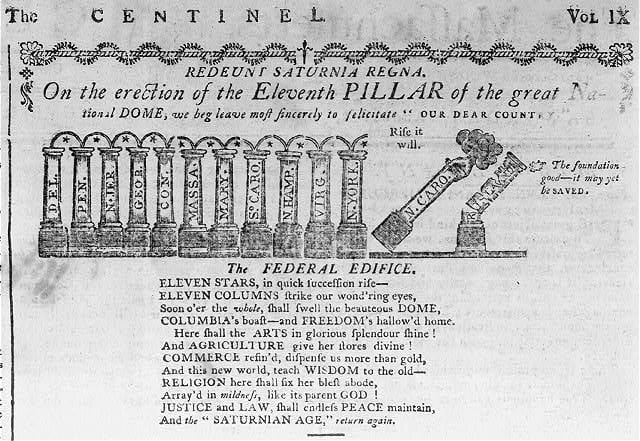

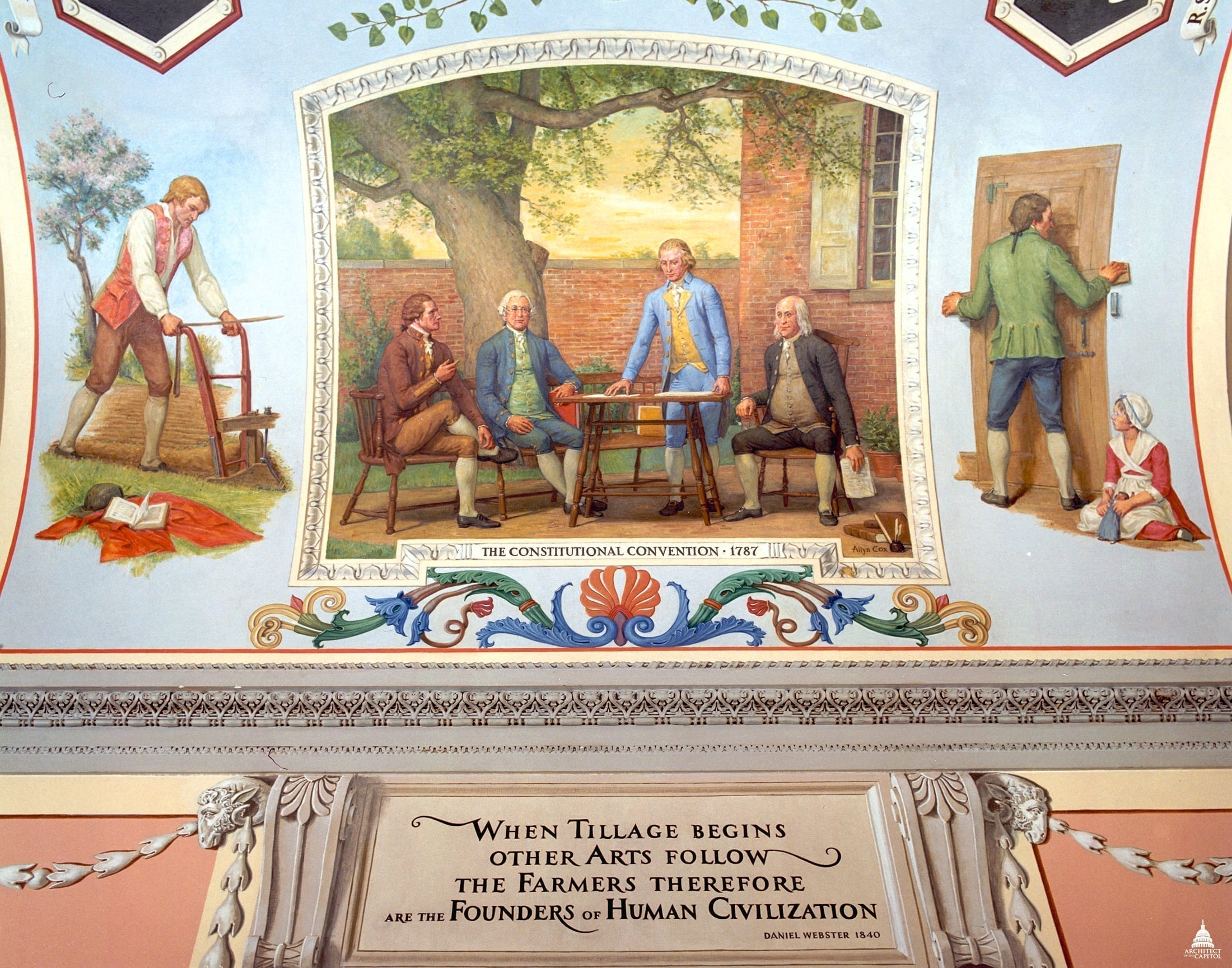

Another major controversy between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists concerned the number of members of the House of Representatives. According to Article I, Section 2, the ratio of representatives to constituents “shall not exceed one for every thirty thousand,” with each state guaranteed at least one representative regardless of population. Until a census could be taken to determine the actual number of inhabitants in each state, the Constitution set the number of representatives for each state as: NH (3), MA (8), RI (1), CT (5), NY (6), NJ (4), PA (8), DE (1), MD (6), VA (10), NC (5), SC (5), and GA (3).

Anti-Federalists argued that having such a small number of representatives would be too aristocratic, turning the national legislature into an elites-only club and fostering class division. They were additionally concerned that since fewer members would mean each represented more people, the representatives would fail to be truly connected to their constituents, and thus, not represent their interests well. On one side, the interests of the people must be amply represented. On the other, deliberation cannot occur if there are too many people in a legislative body. Anti-Federalists argued that a small number of representatives would be too aristocratic, and members would represent too many people to be truly connected to them.

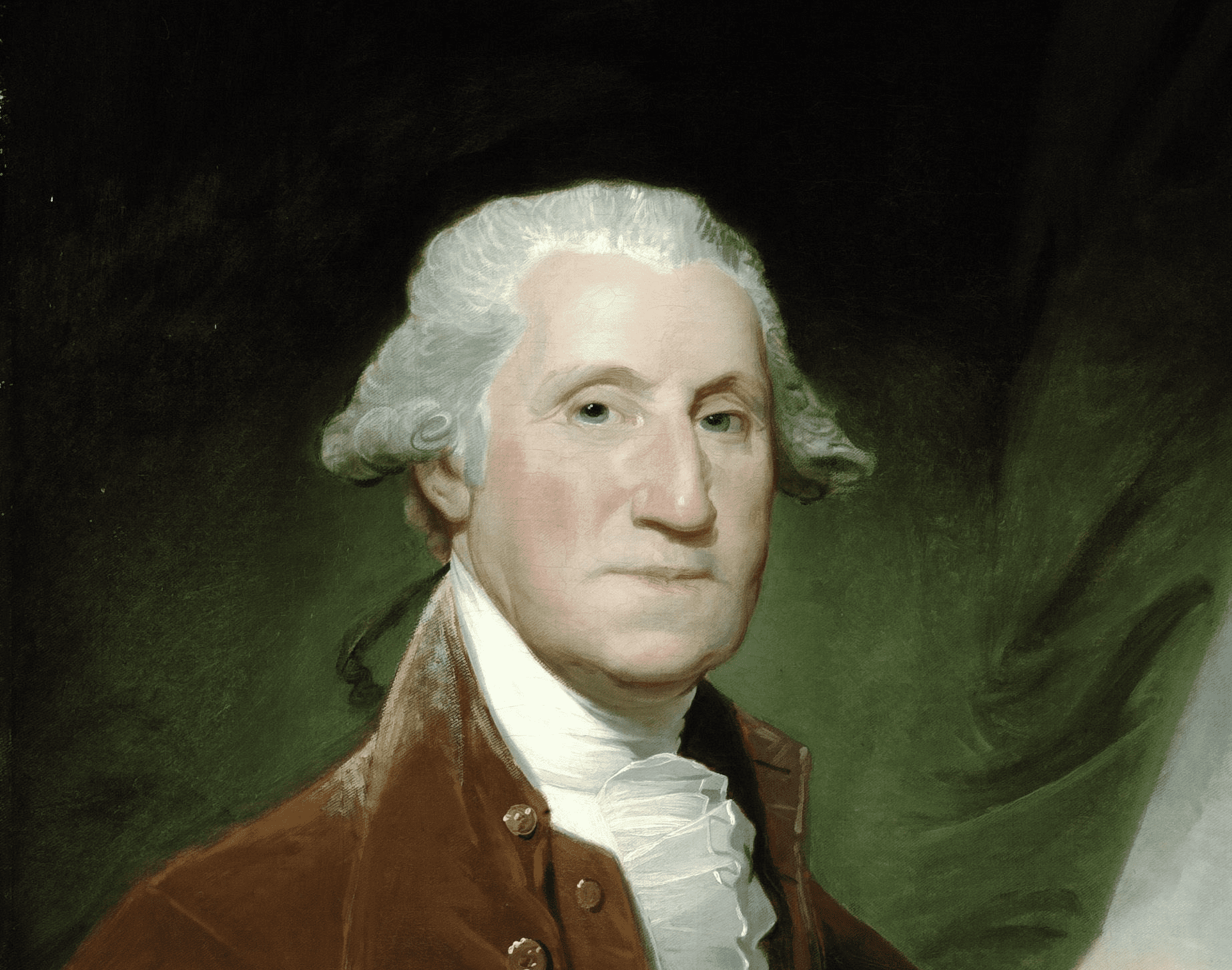

On the other hand, Federalists like Publius cautioned against adding too many members to a legislative body in this essay. Publius suggests that an excessive number of representatives would be unwieldy and create confusion, deterring or even preventing the type of reasoned deliberation necessary in a legislative body. In large bodies, it may well be more difficult for individuals to exercise their powers of ethical judgment and assert unpopular positions, he argues. As in Federalist No. 10, Publius also notes that because members will be elected by a higher number of voters, they are likely to be of higher quality than members of state legislatures.

Source: George W. Carey and James McClellan, eds., The Federalist: The Gideon Edition, (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2001)

To the people of the state of New York:

THE number of which the House of Representatives is to consist, forms another and a very interesting point of view, under which this branch of the federal legislature may be contemplated. Scarce any article, indeed, in the whole Constitution seems to be rendered more worthy of attention, by the weight of character and the apparent force of argument with which it has been assailed. . . . The charges exhibited against it[1] are, first, that so small a number of representatives will be an unsafe depositary of the public interests; secondly, that they will not possess a proper knowledge of the local circumstances of their numerous constituents; thirdly, that they will be taken from that class of citizens which will sympathize least with the feelings of the mass of the people, and be most likely to aim at a permanent elevation of the few on the depression of the many; fourthly, that defective as the number will be in the first instance, it will be more and more disproportionate, by the increase of the people, and the obstacles which will prevent a correspondent increase of the representatives.

In general it may be remarked on this subject, that no political problem is less susceptible of a precise solution than that which relates to the number most convenient for a representative legislature; nor is there any point on which the policy of the several states is more at variance, whether we compare their legislative assemblies directly with each other, or consider the proportions which they respectively bear to the number of their constituents. Passing over the difference between the smallest and largest states, as Delaware, whose most numerous branch consists of twenty-one representatives, and Massachusetts, where it amounts to between three and four hundred, a very considerable difference is observable among states nearly equal in population. The number of representatives in Pennsylvania is not more than one fifth of that in the state last mentioned. New York, whose population is to that of South Carolina as six to five, has little more than one third of the number of representatives. As great a disparity prevails between the states of Georgia and Delaware or Rhode Island. In Pennsylvania, the representatives do not bear a greater proportion to their constituents than of one for every four or five thousand. In Rhode Island, they bear a proportion of at least one for every thousand. And according to the constitution of Georgia, the proportion may be carried to one to every ten electors; and must unavoidably far exceed the proportion in any of the other states.

Another general remark to be made is, that the ratio between the representatives and the people ought not to be the same where the latter are very numerous as where they are very few. Were the representatives in Virginia to be regulated by the standard in Rhode Island, they would, at this time, amount to between four and five hundred; and twenty or thirty years hence, to a thousand. On the other hand, the ratio of Pennsylvania, if applied to the state of Delaware, would reduce the representative assembly of the latter to seven or eight members. Nothing can be more fallacious than to found our political calculations on arithmetical principles. Sixty or seventy men may be more properly trusted with a given degree of power than six or seven. But it does not follow that six or seven hundred would be proportionably a better depositary. And if we carry on the supposition to six or seven thousand, the whole reasoning ought to be reversed. The truth is, that in all cases a certain number at least seems to be necessary to secure the benefits of free consultation and discussion, and to guard against too easy a combination for improper purposes; as, on the other hand, the number ought at most to be kept within a certain limit, in order to avoid the confusion and intemperance of a multitude. In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever character composed, passion never fails to wrest the scepter from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.[2]

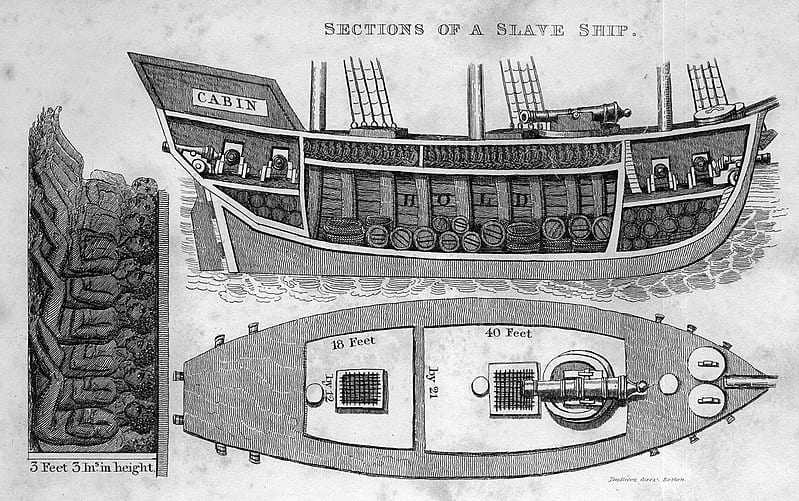

. . . With these general ideas in our mind, let us weigh the objections which have been stated against the number of members proposed for the House of Representatives. It is said, in the first place, that so small a number cannot be safely trusted with so much power. The number of which this branch of the legislature is to consist, at the outset of the government, will be sixty-five. Within three years a census is to be taken, when the number may be augmented to one for every thirty thousand inhabitants; and within every successive period of ten years the census is to be renewed, and augmentations may continue to be made under the above limitation. It will not be thought an extravagant conjecture that the first census will, at the rate of one for every thirty thousand, raise the number of representatives to at least one hundred. Estimating the negroes in the proportion of three-fifths, it can scarcely be doubted that the population of the United States will by that time, if it does not already, amount to three millions. At the expiration of twenty-five years, according to the computed rate of increase, the number of representatives will amount to two hundred, and of fifty years, to four hundred. This is a number which, I presume, will put an end to all fears arising from the smallness of the body. I take for granted here what I shall, in answering the fourth objection, hereafter show, that the number of representatives will be augmented from time to time in the manner provided by the Constitution.[3]

On a contrary supposition, I should admit the objection to have very great weight indeed. The true question to be decided then is, whether the smallness of the number, as a temporary regulation, be dangerous to the public liberty? Whether sixty-five members for a few years, and a hundred or two hundred for a few more, be a safe depositary for a limited and well-guarded power of legislating for the United States? I must own that I could not give a negative answer to this question, without first obliterating every impression which I have received with regard to the present genius of the people of America, the spirit which actuates the state legislatures, and the principles which are incorporated with the political character of every class of citizens I am unable to conceive that the people of America, in their present temper, or under any circumstances which can speedily happen, will choose, and every second year repeat the choice of, sixty-five or a hundred men who would be disposed to form and pursue a scheme of tyranny or treachery. I am unable to conceive that the state legislatures, which must feel so many motives to watch, and which possess so many means of counteracting, the federal legislature, would fail either to detect or to defeat a conspiracy of the latter against the liberties of their common constituents. I am equally unable to conceive that there are at this time, or can be in any short time, in the United States, any sixty-five or a hundred men capable of recommending themselves to the choice of the people at large, who would either desire or dare, within the short space of two years, to betray the solemn trust committed to them. What change of circumstances, time, and a fuller population of our country may produce, requires a prophetic spirit to declare, which makes no part of my pretensions. . . .

- 1. Article I, Section 2

- 2. In ancient Athens, a pure democracy, every male citizen participated directly in legislation. The result was a form of mob rule. Political philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle criticized the notion of pure democracy because of this tendency. Publius is arguing that even good citizens, such as Socrates, one of the founders of Western philosophy, would succumb to the impulses of mob rule in a system of pure democracy.

- 3. See Federalist No. 58

“Elihu” Essay

February 18, 1788

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Our Core Document Collection allows students to read history in the words of those who made it. Available in hard copy and for download.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)