Stephanie Nelson: Why MAHG?

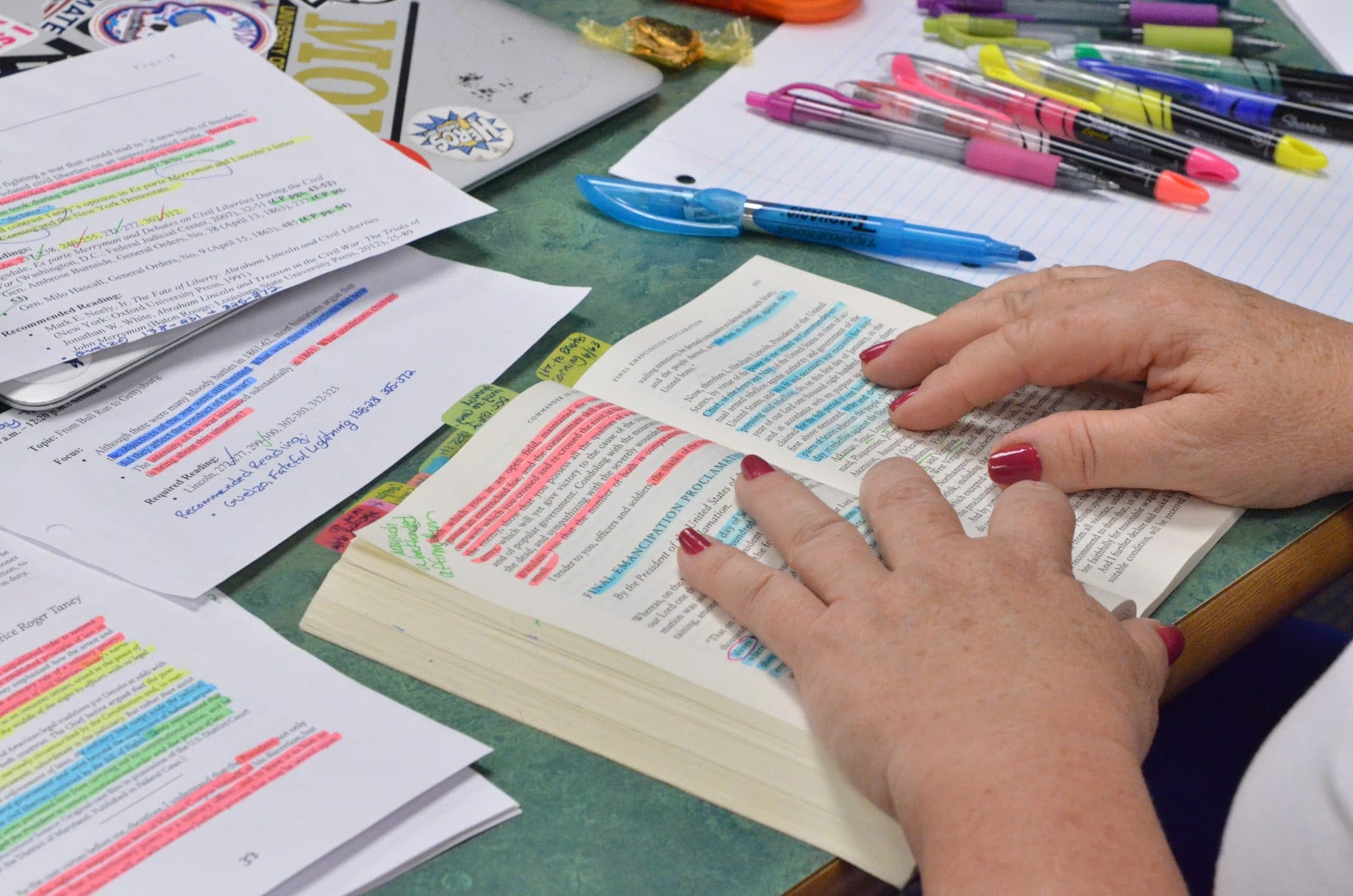

At a recent Teaching American History weekend seminar in San Diego, Stephanie Nelson relived her experience in the Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) program. The seminar, on “the role of Thomas Jefferson in the creation of the American Republic,” was a lively discussion of primary documents, led by Jefferson scholar Robert McDonald of West Point. Before the seminar, Nelson read through the packet of primary documents TAH sent her, annotating interesting passages and writing questions in the margins. Arriving in San Diego, she met fifteen other teachers who were as ready to talk about Jefferson’s many complexities as she was. They’d done the reading, too, and they pointed to particular passages as they made their comments, “not going off on random tangents.”

What’s Unique About MAHG

Nelson graduated from MAHG in August 2021. Before beginning the degree, she hadn’t looked for a program centered around discussion of primary documents. She simply wanted to build her content knowledge. She had sampled the online options in in Gilder Lehrman’s well-known program, intrigued by its engagingly wide variety of course topics, all taught by famous scholars. Yet the format was asynchronous and self-paced. “It was ‘watch this lecture, then complete this assignment. It wasn’t done in real time,” Nelson said. Two of the seven lectures for each course were given by “a master teacher who offered teaching strategies. We wrote two or three papers, but these were graded not by the professor who gave the lecture, but by a teaching assistant.” She did not get to know other students taking the same course, and she had no interaction with the scholars teaching the history content, either.

At the time, Nelson didn’t know a different option existed for working teachers. But she had two friends, both Madison Fellows, who had earned degrees in Ashland University’s Master of Arts in American History and Government program. They encouraged her to apply for a Madison Fellowship and to check out the MAHG program.

Awarded a Madison Fellowship for the state of Washington in 2018, Nelson sent an inquiry to Chris Pascarella, Director of MAHG. Pascarella’s response showed he thoroughly understood Madison program’s requirements. “I didn’t want to have to think too hard about the Madison program’s paperwork,” she admitted. She decided to “go with my friends’ recommendation.”

She found MAHG to be “a rigorous yet supportive program. Even during the online classes, you’re building a community” with the other teachers taking the course, Nelson said.

Nelson was impressed by the “scholarship” of the professors who taught her in the MAHG program. Drawn not only from Ashland University but from colleges and universities around the country, the faculty are made up of specialists in all the eras of US history and all the institutions of American government. Yet the professors’ seriousness did not make them unapproachable. They loved talking about history and government with the teachers in the program. “Most of the professors will say, ‘Contact me anytime if you have questions. I’m here to help.’”

The Challenge and Benefit of Conversation

To other teachers choosing a Master’s program, Nelson says, “MAHG is challenging—but you’re going to know more when you’ve finished it. Each professor has your interest at heart.”

For Nelson, part of the challenge was stepping up to the seminar conversation. During one of her first interactive online courses, Nelson’s professor, Abbilyn Sellars (of Azusa Pacific University), emailed her to urge her to speak more often. Nelson had been quiet, intending to join the discussion when she had “a nugget to contribute.” But she learned to speak while still mulling over her ideas. She found she could do so without feeling pressured. The energy in each seminar was mutually supportive. If some teachers taking the course had more to say about certain readings, others entered the conversation when the class moved to the next reading.

The format made room for her to admit her questions about the readings, and she was glad her questions “could be answered in real time by an expert.”

Conversation Deepens Learning

Nelson’s own approach to teaching changed. At Raisbeck Aviation High School, a public “choice” school themed around the science and history of aerospace engineering, Nelson currently teaches US history, Advanced Placement US History, and Civics. She now enjoys “supporting students in discussion more,” realizing it awakens “curiosity.” To push students’ thinking she may simply ask, “What are you wondering about? What are you noticing?” For some students, who “are really good at speaking but maybe not strong writers, discussion offers a good entry point for thoughts that can transfer to writing. I can say to the student, ‘Hey, you made a good comment. Write that down.’”

Conversation about primary documents allows students to examine complexities that cannot be reduced to simple explanations. That’s what had benefitted Nelson during her MAHG studies and during the recent multiday seminar on Jefferson. If any major figure in American history is complex, it is Jefferson. Nelson’s students are observant. While studying the Louisiana Purchase, they noticed that Jefferson’s unilateral decision to buy a vast tract of western territory from Napoleon “didn’t match up with his view of executive powers.” The challenge with Jefferson—as with much of American history, Nelson said—is to recognize the contradictions while celebrating the achievements. Only by talking it through can students make mental space for both realities.

STEM Students Appreciate History and Civics

Although Nelson’s high school has an ostensible STEM focus, “some students love the humanities.” Some are incredibly grateful for the knowledge she offers in civics, a course that students don’t take until their senior year, and then for only one semester. After a lesson on local government, “one of my students came up to me, saying, ‘Why did I not learn this before?’ He was not aware that his town was governed through a city council, or that his school system was overseen by an elected school board.” Nelson had asked her students—who come from a variety of towns within King County, Washington—to each research their own council and school board representatives, as well as the candidates running for these offices. “I’m really glad we’re getting to talk about this,” the student said.

Civics class allows Nelson to relate history to current concerns, while using “live” primary sources. Nelson’s students watched a portion of the recent Senate hearings on Biden’s recent nominee to the Supreme Court, Ketanji Brown Jackson. Seeing the hearings as “a job interview,” students questioned the different attitudes struck by Senators of opposite parties. “If this is one of the most important jobs in government, why are all the hard questions coming from the Republicans? Everybody should be asking her hard questions!” they said. “I get what you’re saying,” Nelson replied. “But had there been no cameras in the room, some of the Senators might have posed different questions. They want to be reelected. And they want to show their constituents their political perspectives and expertise on judicial subjects.”

Discovering this reality doesn’t necessarily make students cynical about government. Students’ trust or distrust of governmental processes follows more from their own life experience, Nelson finds. What’s important is that they never “stop questioning and learning. That helps us all to grow.”

Interested in finding out more about our degree programs? Click here.