Teaching Dred Scott with Ryan DeMarco

Ryan DeMarco tells his APUSH students what he learned at a Teaching American History Seminar about the Dred Scott decision.

Visiting the Teaching American History website, Ryan DeMarco was delighted to learn of a free online, interactive seminar on “Slavery and Its Consequences,” to be taught by Eric Sands of Berry College. DeMarco is the history department chair at North Cross School in Roanoke, Virginia—a city at some distance from larger cities where in-person seminars are often held. He’d been looking for “a discussion,” not a lecture, on American history, but one led by a scholar with expertise. “I love being able to ask the professor questions and get clarification,” DeMarco said.

He registered, read the reading packet thoroughly and logged on for the Saturday course.

A Question about the Dred Scott Decision . . .

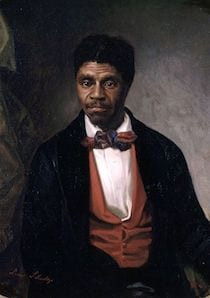

Early in the seminar, Sands led teachers in a discussion of the Dred Scott Decision, issued 165 years ago this month (March 6, 1857). Soon the conversation pushed on to other topics—the reading packet was thick, and the participants were highly engaged. But DeMarco remained unsure of one point: To achieve his evident aim of defeating Scott’s petition, did Chief Justice Roger Taney, who authored the opinion, need to write an opinion so dismissive of Black Americans’ rights?

Scott sued for freedom on the grounds that he had been held by his master for several years in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, areas where slavery was prohibited. On strictly legal grounds, couldn’t Taney have simply claimed Scott’s case had no standing?

Leads to a Post-Seminar Exchange with the Professor . . .

We took DeMarco’s question back to Professor Sands.

Ryan DeMarco asks, “Could Taney have resolved the case more easily than he did, without going on the racist rant that made the ruling famous? Could the Court simply have ruled that Dred Scott lacked standing, because he was not a citizen?”

“Yes, Taney could have made his ruling much simpler and far less pernicious by just denying Scott’s standing to sue—and then dismissed the case,” Professor Sands replied. “There was no reason he needed to go further than this and declare all blacks non-citizens and then to invalidate the Missouri Compromise —Well, other than the fact that, as I think I said in the seminar, Taney thought he was playing the role of a statesman. But the teacher’s instincts on the case are spot on.”

Do you mean that Taney thought that with his ruling he could settle the dissension over slavery once and for all, ending the perilous balancing act Congress had to perform every time it admitted a new state from the western territories?

“Yes, I think Taney thought he had rectified the slavery issue (at least as it pertained to the territories). And part of his ruling was that depriving someone of their slaves in the territories was a violation of the 5th Amendment—that is, of the clause stating: “No person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Taney’s ruling meant that slavery couldn’t be kept out of the territories,” Professor Sands explained.

“It’s kind of staggering how sweeping the ruling was. But, given its breadth, it’s not surprising the ruling led to crisis.”

And New Conversation in the Classroom

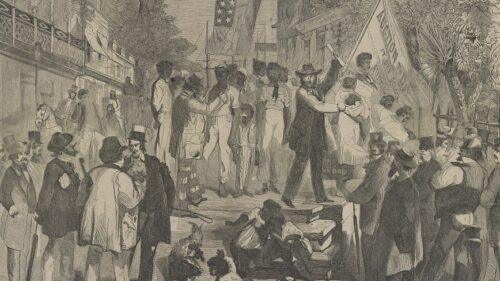

When we shared Sands’ response with DeMarco, he shared what Sands said with his APUSH students. “My students were surprised, suddenly realizing that a single person’s choices can have a major impact on American history. We compared the impact of Taney’s ruling to that of Stephen Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, and John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry. Which event played a greater role in triggering the crisis that led to the Civil War? Of course, the actions of Taney, Douglas and Brown all helped to bring the war.

“I definitely appreciate the historical-legal clarification from Professor Sands,” DeMarco continued, noting that it raised an issue he might discuss in his comparative government class. “I wonder about the role the Supreme Court has played on other occasions, filling the legislative role of Congress when Congress is paralyzed and inept at making new laws to rectify certain issues, particularly more contemporary controversial issues. This history lesson gives me more to talk about with my students.”

Read more about Ryan DeMarco.