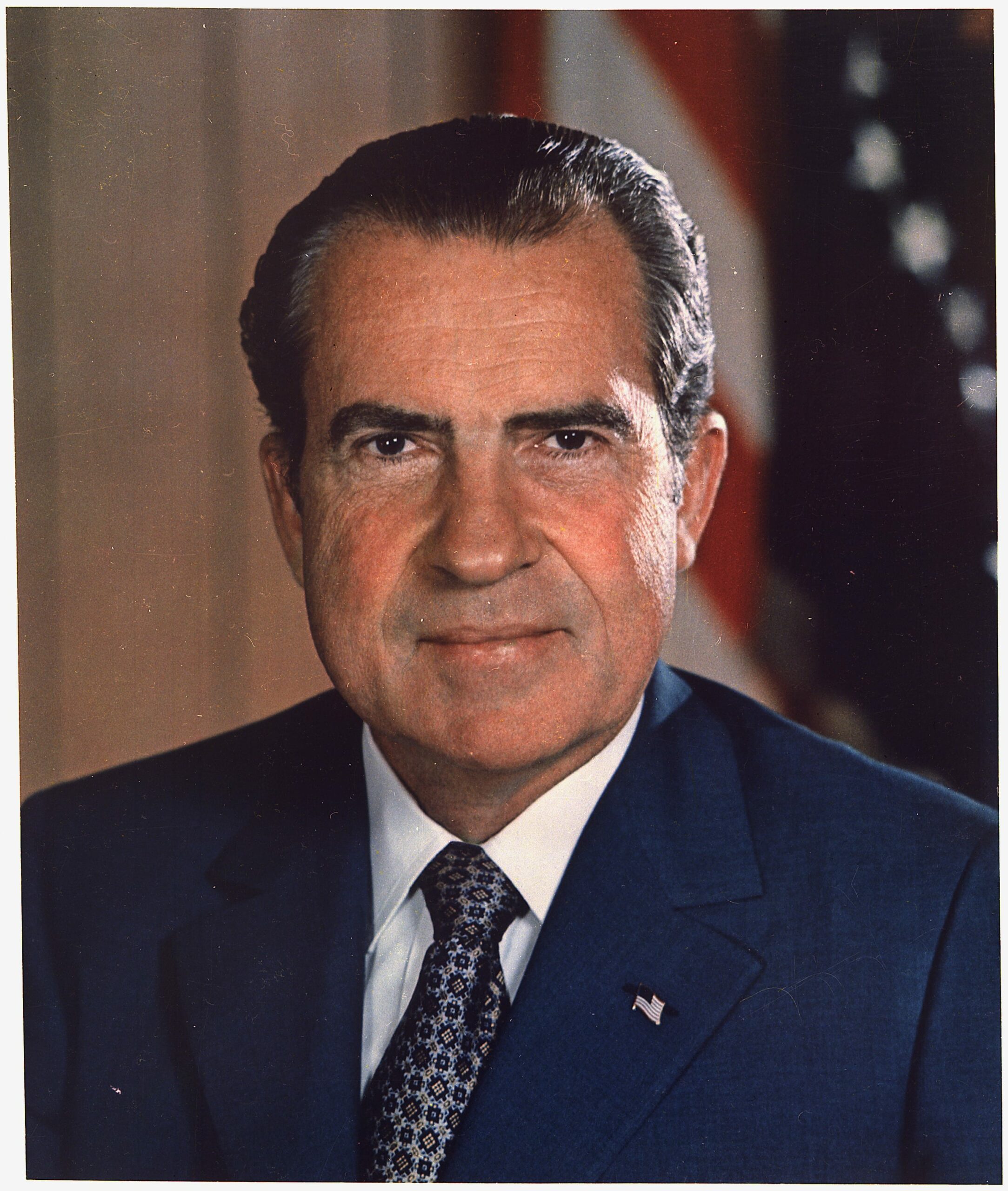

Apart from Richard Nixon’s two-armed-victory-fingered-wave goodbye atop the steps of Marine One preparing to depart the South Lawn of the White House in his final hours as president, John Dean’s hearing before the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities supplied the Watergate scandal its most iconic images. Dean’s testimony immediately took its place among other defining congressional hearings in American history: the 1922 Teapot Dome Scandal proceedings, Whittaker Chambers and Alger Hiss before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1948, and the 1954 Army-McCarthy Hearings, to name only a few. Other marquee hearings would follow including Oliver North’s testimony for Iran-Contra in 1987, Anita Hill’s at Clarence Thomas’s 1991 confirmation hearing, and Hillary Clinton’s at the 2013 Benghazi hearings.

The U.S. Constitution nowhere explicitly grants Congress the authority to launch investigations or to compel testimony as part of its legislative function, but such activities were established features of the British Parliament and various assemblies of the American colonies by the time the Constitution was written. Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 gives the Senate the responsibility for “Advice and Consent” regarding the approval of treaties, along with the appointment of an array of public figures. With the exercise of these responsibilities have developed a wide array of exploratory and investigative functions that (in theory) enable Congress to understand and carry out its broader Constitutional duties. Such hearings and investigations have become among the most visible spaces for public review, accountability, and, of course, theatre.

It was June 25, 1973 when the recently fired White House Counsel, John Dean, first appeared before the Select Committee to explain his knowledge of and involvement in the growing Watergate scandal—and that of the President. Formed the previous February by a unanimous vote in the Senate, the committee began its work of investigating suspected links between the Nixon White House and the break-in at the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters in the Watergate office complex in June of 1972. Also in February, the acting FBI Director, L. Patrick Gray, gave testimony before a different Senate committee—Judiciary—to confirm him as J. Edgar Hoover’s first permanent successor (note: he was never confirmed). Gray revealed that the Nixon White House had taken special interest in the FBI’s investigation of Watergate and that the FBI was giving daily updates to the Nixon officials. Gray also suggested that Dean had “probably lied” to FBI investigators.

Gray’s testimony set in motion a chain of events that not only placed Dean on the hotseat before the Senate Watergate Committee in June but arguably resulted in Nixon’s resignation in August of 1974.

John Dean joined the Nixon White House in 1970. A loyal Nixon partisan, he soon occupied an important place in the President’s inner circle. He learned of connections between the White House and the Watergate break-ins (there were two) almost immediately after they happened, and participated in intercepting and destroying evidence soon afterwards. Nixon also pushed Dean to play a leading role in the cover-up, especially engaging in the risky business of trying to buy the silence of the unpredictable Watergate burglars. It was only after he was exposed by Gray in the FBI confirmation hearings that Dean began to understand that Nixon and others—especially John Ehrlichman and H.R. Haldeman—would likely make him a scapegoat for the entire mess. He secretly hired a lawyer and began to cooperate with the Senate committee on April 16, 1973.

Nixon very quickly discovered Dean’s “betrayal” and began to pressure Department of Justice personnel not to offer immunity to any public officials giving testimony to the Senate committee. On April 30, the same day Nixon was pressured to request the resignation of other Watergate insiders, John Ehrlichman and H.R. Haldeman, he fired Dean. The die was cast. The Senate committee granted Dean immunity on May 16, making his public testimony now almost inevitable.

The seriousness of Watergate in the public consciousness had grown slowly but steadily especially since Nixon’s second inauguration. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein at the Washington Post had been writing about the controversy from the beginning, uncovering shocking revelations using anonymous sources. But real public concern didn’t advance until after the conviction and sentencing of the “White House Plumbers” on January 30, 1973. Public interest in the scandal grew steadily. By the time Dean appeared before the committee in June, Americans were dialed in.

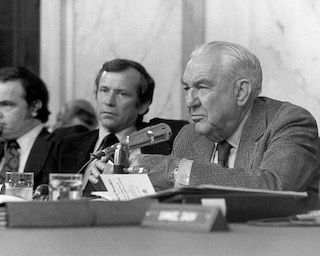

Together with his chief interlocutor, Senator Sam Ervin, Jr., Dean put on a powerful, though understated show. As Nixon biographer her John A. Farrell put it, “For five days the country was riveted as, dressed and coiffed like a straightlaced junior partner, with his blond wife sitting primly behind him, [Dean] dispassionately detailed the White House horrors and Nixon’s attempt to conceal them.” He detailed his own and Nixon’s involvement in the Watergate cover-up and revealed the administration’s long penchant for “dirty tricks” of all kinds. As he testified about shredding documents, laundering money, and paying bribes, he detailed the infamous and growing “cancer on the presidency.”

While Dean’s testimony helped mobilize public opinion, it had no real impact legally. It was Dean’s word against Nixon’s. It wasn’t until the discovery of Nixon’s taping system amid Senate committee testimony by Nixon aid Alexander Butterfield—and after the long legal effort to force the release of tape-recorded conversations in the Oval Office—that “smoking gun” evidence would emerge to corroborate Dean’s claims. By then, the public confidence in Nixon had eroded almost entirely and his days as president were numbered.

There is little doubt but that Dean’s appearance before the Senate Watergate Committee fifty years ago marked something like the beginning of the end of Nixon’s presidency. It stands as a watershed moment in this scandal—if not in the larger history of presidential malfeasance. It also illustrates the strange, uncertain standing of public congressional hearings both in American jurisprudence and in the courts of public opinion.