The Elaine Race Massacre

On this day in 1919, during a union meeting of African American tenant farmers in rural Arkansas, white law enforcement and union members exchanged gunfire, triggering one of the worst race massacres in US history.

At an online Teaching American History seminar last spring, Professor David Krugler facilitated a discussion of documents detailing the massacre and the protracted legal battle that followed, when African American citizens in Elaine were arrested and convicted of purported murders and terrorism against whites. The seminar, “African Americans After World War I,” covered a series of violent racial incidents that occurred in 1919, as Black veterans of the war in Europe returned home, determined to push for greater economic opportunities. Whites in many communities saw such African American aspiration as unwanted economic competition.

Much of the violence occurred in cities. The violence in Elaine was unique in that it followed an attempt of black farmers to break free of the sharecropping system that minimized their earnings and often kept them indebted to the owners of the land they worked. Although that effort failed, in the aftermath of the massacre, an NAACP legal effort to defend victims of the violence—who had been unjustly accused of fomenting it—achieved a degree of success.

Krugler’s book 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back (Cambridge University Press, 2014), explains the circumstances of the Elaine Massacre. It occurred in reaction to the organization in Phillips County, Arkansas of a new labor group, the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America. Designed to function partly as a purchasing alliance, with members buying shares that would allow the group to invest in farmland, the union also tried to pressure local landowners to offer more generous contracts to tenant farmers. In 1919, with cotton prices still high due to demand created by the war, the union hired a Little Rock lawyer to sue for the right to sell a larger share of the cotton crop they had for their landlords.

Krugler’s book 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back (Cambridge University Press, 2014), explains the circumstances of the Elaine Massacre. It occurred in reaction to the organization in Phillips County, Arkansas of a new labor group, the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America. Designed to function partly as a purchasing alliance, with members buying shares that would allow the group to invest in farmland, the union also tried to pressure local landowners to offer more generous contracts to tenant farmers. In 1919, with cotton prices still high due to demand created by the war, the union hired a Little Rock lawyer to sue for the right to sell a larger share of the cotton crop they had for their landlords.

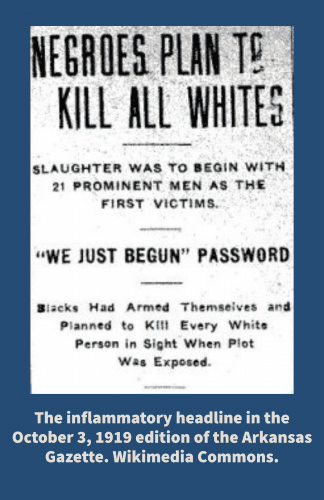

Although—or because—African American citizens in Phillips County outnumbered whites by ten to one, the disadvantageous terms offered Black tenant labor had been maintained through violence and intimidation. Fearing a violent attempt to disrupt their meetings, the union posted armed guards. When representatives of the county’s law enforcement arrived outside a meeting held on the evening September 30, an exchange of gunfire was triggered, and a white deputy sheriff was killed. This precipitated a massacre the following day, when several hundred white citizens of the surrounding counties poured into the area around the small town of Elaine, bent on stopping what they saw as an African American “insurrection.”

After the Arkansas governor persuaded the War Department to send troops from nearby Camp Pike to restore order in Elaine, the white mobs dispersed, but the ordeal of the Black citizens continued. The troops cooperated with the local power structure. They arrested African Americans, holding them in hastily constructed stockades until white landowners arrived to give evidence of their guilt or innocence as insurrectionists. Of the hundreds arrested, 122 were jailed and charged with murder or behavior threatening murder. Hasty trials of the first dozen of the accused followed, resulting in convictions and death sentences, and leading the remaining prisoners to accept plea bargains and lengthy prison terms.

After the Arkansas governor persuaded the War Department to send troops from nearby Camp Pike to restore order in Elaine, the white mobs dispersed, but the ordeal of the Black citizens continued. The troops cooperated with the local power structure. They arrested African Americans, holding them in hastily constructed stockades until white landowners arrived to give evidence of their guilt or innocence as insurrectionists. Of the hundreds arrested, 122 were jailed and charged with murder or behavior threatening murder. Hasty trials of the first dozen of the accused followed, resulting in convictions and death sentences, and leading the remaining prisoners to accept plea bargains and lengthy prison terms.

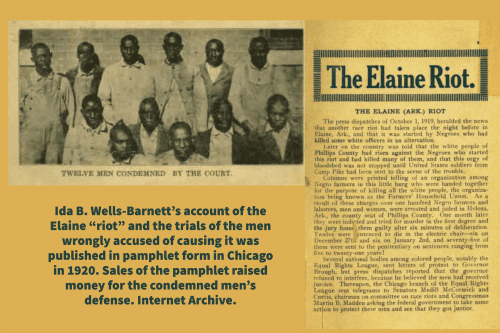

Monitoring these events with alarm, African American activists took action. Journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett traveled to Arkansas to interview the condemned men. The NAACP sent a staff member who was well positioned to investigate what had happened in Elaine: Walter White, whose mixed-race ancestry and Caucasian appearance allowed him to speak confidentially with white locals. White’s report laid the groundwork for an appeal of the convictions, while Wells’ reporting drew financial contributions to the effort. After five years of complicated litigation, the men were finally released, although not formally exonerated. Six were freed on the grounds of improper trial procedures. The other six were pardoned of “second-degree murder.”

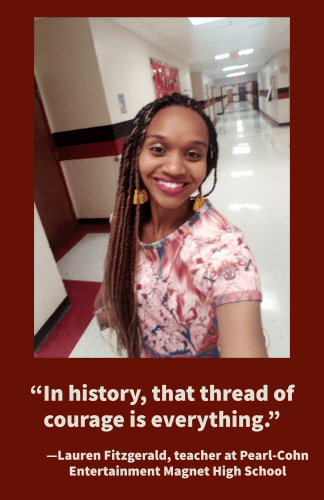

One teacher who participated in the TAH seminar thanked Krugler for facilitating it and for providing teachers with primary sources rarely excerpted in textbooks and lesson plans: news articles, political cartoons, photos, poems and government reports. You can read Lauren Fitzgerald’s comments on the documents covered in the seminar—which she plans to use in her own classroom—here.

Fitzgerald’s comments are particularly intriguing during a period of divisiveness over how best to teach the uncomfortable aspects of American racial history. She teaches at a school with a high minority student population and teaching staff and a unique focus and mission: Pearl-Cohn Entertainment Magnet High School in Nashville. The school offers students remarkable opportunities to build skills transferrable to media careers. Yet in her role as a history teacher, Fitzgerald understands herself as helping students to build less tangible, more fundamental skills and character traits: historical empathy and historical forgiveness, along with the self-respect that empowers moral decision-making.

Fitzgerald’s comments are particularly intriguing during a period of divisiveness over how best to teach the uncomfortable aspects of American racial history. She teaches at a school with a high minority student population and teaching staff and a unique focus and mission: Pearl-Cohn Entertainment Magnet High School in Nashville. The school offers students remarkable opportunities to build skills transferrable to media careers. Yet in her role as a history teacher, Fitzgerald understands herself as helping students to build less tangible, more fundamental skills and character traits: historical empathy and historical forgiveness, along with the self-respect that empowers moral decision-making.