The Fight for a Federal Anti-Lynching Law

Over 122 years of effort preceded the passage of the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act, signed into law by President Biden on March 29, 2022. According to Michelle Duster, the great-granddaughter and biographer of anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, more than 200 earlier bills to make lynching a federal crime failed to pass through Congress. The first was proposed to Congress in 1900 by Representative George Henry White of North Carolina, the only African American serving in Congress at that time. Even earlier, Wells had urged President William McKinley to recommend such a law to Congress. These efforts and many later ones were frustrated by arguments that, under the Constitution, Congress had no authority to overwrite the criminal law of the states.

Wells’ Fight to Criminalize Lynching

Wells was one of the first, if not the first, journalist to point out the falsity of the usual justification for lynching: that it was the community’s outraged response when black men assaulted white women. The case that impelled her lifelong fight against racist violence occurred in Memphis, early in Wells’ career as a journalist. Three of her friends, a black grocery store owner and his employees, were lynched after they used firearms to defend their store from an armed attack by friends of a rival white store owner. The economic motive for the lynching was clear, yet the action backfired when African Americans responded to the event by leaving Memphis in droves. Wells’ newspaper, the Free Press, had published an editorial advising black citizens to leave, since

The city of Memphis has demonstrated that neither character nor standing avails the Negro if he dares to protect himself against the white man or become his rival. . . . There is therefore only one thing left that we can do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out ant murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons.

Some weeks later, the owners of the local streetcar company visited Wells, claiming they had no idea why black citizens were leaving and asking her to use her editorial influence to arrest the exodus, since it was costing them considerable business. Wells pointed out the obvious cause of their loss, adding that “We have learned that every white man of any standing in town knew of . . . and consented to the lynching of” the black store’s owner and his employees. She then wrote another editorial encouraging black citizens who remained in Memphis to continue boycotting the streetcars. A later editorial from her pen accused white citizens of attempting to corrupt black women (the obverse of the charge being leveled against black men). In retaliation for these editorials, a mob attacked and destroyed the newspaper office and press where Wells worked while she was out of town. They publicized a threat to kill Wells if she returned to Memphis. Relocating to Chicago, Wells began documenting all the lynchings she heard of, often visiting the locations where they occurred to interview witnesses. She took her fight against “lynch law” to northeastern cities, and eventually to England, appealing to the British to help with her protest.

Wells felt the federal government had clear cause to act when, in February 1898, an African American man who had just been appointed postmaster in Anderson, South Carolina was murdered along with his entire family. An angry mob set fire to his home, shooting those who tried to escape. In her autobiography, Wells notes, “we thought that now the federal government could step in and punish the perpetrators of this outrage against a federal officer.” Wells travelled to Washington, DC to visit McKinley and make her plea. McKinley received Wells courteously, assuring her that he had already sent secret service agents to investigate the lynching of the postmaster. But he was soon preoccupied with the war Congress had declared against Spain, and made no effort to fulfill Wells’ request.

Wells went on documenting and protesting violence against African Americans throughout her long career. She continued to press for anti-lynching legislation, winning success in her own state of Illinois. She and other civil rights leaders in Chicago persuaded Governor Charles Deneen to draft a set of anti-lynch laws that were enacted in 1905. The laws met a serious political test when an unemployed black man was lynched in Cairo, Illinois in 1909.

The sheriff, who had charged the man with murdering a white woman, took him out of jail and allowed him to be seized by a mob. In accordance with the new law, the sheriff was removed from office, but immediately petitioned the governor for reinstatement. Some black citizens, viewing the sheriff as an ally who, unlike his Democratic replacement, had employed black deputies, backed the sheriff’s request. Wells traveled to Cairo and interviewed witnesses, finding no one, even among the sheriff’s supporters, who gave evidence that he had made any effort to protect the prisoner from the mob. She appeared at the reinstatement hearing and rebuked all those who supported the sheriff, predicting an escalation of lynchings would ensue if the violation of law went unpunished. The sheriff’s supporters backed down, even admitting their error, and the governor refused to reinstate the sheriff, signaling that the 1905 laws would be enforced. Wells credited Governor Deneen with ending the practice of “lynch law” in Illinois.

The Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill

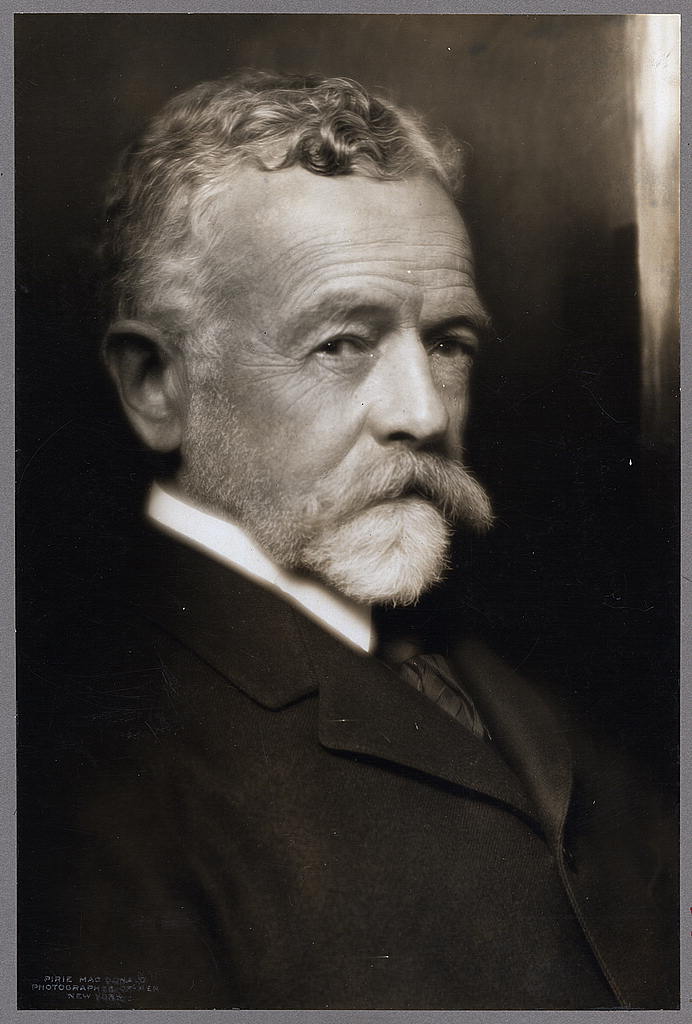

Such reforms being unheard of in southern states, the fight for a federal anti-lynching law continued. One of the more intense campaigns occurred between 1918 and 1922. Republican Representative Leonidas C. Dyer of Missouri introduced H.R. 11279 on April 18, 1918, “to protect citizens of the United States against lynching in default of protection by the States.” Dyer decided to act because of mob violence the summer before In East St. Louis. A white mob, infuriated that black migrants from the South were competing with them for jobs and housing, attacked a black neighborhood, causing 47 deaths and the exodus of most of the black population from the city. Many of those who fled ended up in Representative Dyer’s district, becoming his constituents.

Dyer grounded his argument in the Fourteenth Amendment. When states refused to prosecute those involved in lynching, the victims of the crime were denied equal protection of the laws. To those who argued that the Congress had no authority to legislate on matters of social policy within the states, he pointed out that Congress had already passed laws regulating child labor throughout the country and had moreover passed the Eighteenth Amendment, forbidding the sale of alcohol within the states.

Dyer’s original bill offered comprehensive measures to force states and counties to prosecute offenders. It not only proposed to try members of lynch mobs in federal court; it proposed fines against counties where lynching occurred and fines on state and local law enforcement officers who surrendered prisoners to murderous mobs. It even established guidelines for the selection of impartial juries in lynching cases.

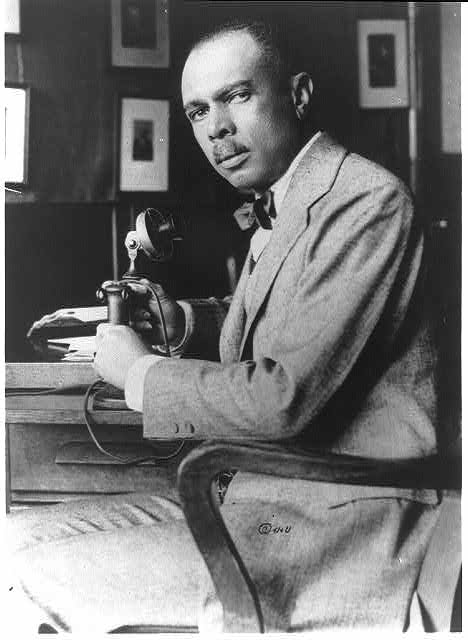

The NAACP Campaign

At first the bill made little headway, remaining stalled in the House Judiciary committee. In early 1919, the NAACP launched an effort to push the bill, publishing a report, Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889–1919. Soon afterward, James Weldon Johnson, NAACP Executive secretary, began lobbying congressmen to move the bill forward, often visiting Dyer to encourage him to keep up the fight.

Johnson’s autobiography details the NAACP’s fight for a federal anti-lynching law—the careful data collection that led to the 1919 report; Johnson’s constant lobbying of congressmen and senators; and the political maneuvers that led to the passage of an amended version of the bill through the Republican-controlled House in January 1922. He also describes the difficult battle that followed in the Senate, where the Republican Chairman of the Judiciary Committee, William Borah of Idaho, professed uncertainty about the bill’s constitutionality. “The gist of the argument” that troubled Borah, Johnson writes, “was that lynching is murder and, therefore, the federal government has no more constitutional right to step into a state and punish lynching than it has to do likewise and punish murder.” Johnson countered this argument when he testified before Borah’s Committee:

Lynching is murder, but it is also more than murder. In murder, one or more individuals take life, generally, for some personal reason. In lynching, a mob sets itself up in place of the state and acts in place of . . . . due processes of law guaranteed by the Constitution to every person accused of crime. In murder, the murderer merely violates the law of the state. In lynching, the mob arrogates to itself the powers of the state and the functions of government. The Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill is aimed against lynching not only as murder, but as anarchy—anarchy which the states have proven themselves powerless to cope with.

James Weldon Johnson, Testimony Before Senate Judiciary Committee, 1922

Johnson’s logic echoes that of Lincoln in 1832, when he warned in his Lyceum Address that mob violence could undermine self-government itself.

Political Maneuvers Blocking the Law

No doubt Johnson’s testimony helped to ensure the bill being reported out of the Judiciary Committee for consideration on the Senate floor. At this point, however, the Senate Majority leader, Republican Henry Cabot Lodge, showed little eagerness to continue. Lodge’s inactivity puzzled Johnson, since the Senator had earlier favored federal protections for African American civil rights.

Although Johnson does not explicitly accuse Lodge of deliberately tanking the bill, he tells us that Lodge asked the young and inexperienced Senator Shortridge of California to shepherd it on the floor. He describes Shortridge’s elaborate courtesies toward southern Democratic senators who repeatedly interrupt him with points of order, and Shortridge’s insistence on making a long speech during which several southern senators exited the Senate, depriving it of a quorum and preventing a vote. Later, he describes his dismay when he reads in the newspapers that the Republican leadership have decided to permanently abandon the bill, due to southerners’ threats of a filibuster that would prevent any other legislation being passed.

“It would be difficult for me to tell just what my feelings were,” Johnson says. “I think disgust was the predominate emotion. . . . My thoughts were made the more bitter by a fact which I knew and which every Senator admitted, the fact that the bill would have been passed had it been brought to a vote.” Johnson, who had “tramped the corridors of the Capitol and the two houses so constantly” during the campaign to pass the law that he could “have found my way about blindfolded,” had counted all the votes, and knew they constituted a majority.

Upholding Constitutional Self-government

Summarizing the NAACP campaign between 1918 and 1922, Johnson declares that although the Dyer bill did not become law, “it made the floors of Congress a forum in which the facts were discussed and brought home to the American people as they had never been before. Agitation for the passage of the measure was, without a doubt, one of the prime factors in reducing the number of lynchings in the decade that followed to one-third of what it had been in the preceding decade . . . . It served to awaken the people of the Southern states to the necessity of taking steps themselves to wipe out the crime,” he concludes.

It’s true that, by the time of Emmett Till’s murder, lynching had ceased to be a spectacle carried out and witnessed as entertainment by a mob. It had become an extralegal execution planned and carried out in comparative secrecy, under cover of night. Yet it remained, in the South, a way of punishing and preventing perceived threats to white supremacy. Naming the Emmett Till Anti-lynching Act after Mamie Till’s beloved son symbolizes a nation’s regret for allowing decades of racist violence. But it also signals a gathered determination on the part of the American majority to condemn and prevent the use of terror to undermine constitutional protections for individual rights or to circumvent constitutional self-government.