The Importance of the 15th Amendment

The 15th Amendment was the third and final constitutional change of Reconstruction, hailed then and since as a profound leap in American democracy. And though the story of its deliberation, enactment, and enforcement illustrates its great potential impact, many of those possibilities were only realized in the mid-20th century by the efforts of the Civil Rights Movement. Even today, 153 years since its ratification, the scope of the 15th Amendment remains uncertain.

The congressional road to the 15th Amendment actually begins in the 1866 debates of the 14th, which was itself an attempt to reinforce the principles of the 13th. Section 2 of the 14th Amendment sought to penalize states for disenfranchising prospective male voters by reducing their House representation. In this way it encouraged voting rights for black men without imposing them — a strategy aimed at compromise. Nonetheless, congressional Democrats presented black political power, and specifically voting, as a boogieman to unify their resistance to the 14th Amendment in Congress and rally the (unsuccessful) opposition to its ratification. So despite its passage, Democratic opposition to the 14th Amendment showed that future voting rights laws would effectively be an intra-party debate among Republicans.

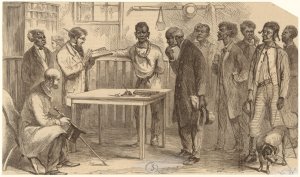

Between their successes in the 1866 midterms (with Republicans winning clear supermajorities in both chambers) and the 1868 presidential election, Republicans carefully leveraged their political power to expand voting rights. This took the form of combined persuasion and pressure campaigns. In Republican-controlled states, they encouraged local action like referendums to enfranchise black men. In places where the federal government had more direct authority, they passed laws and applied pressure by eliminating racial restrictions to voting in Washington D.C. and the federal territories; requiring former Confederate states to do the same for readmission; and rejecting Nebraska’s petitions for statehood until they followed suit. While these efforts advanced the cause of suffrage, they faced more resistance than anticipated, and the referendum movement in particular was less successful than envisioned. This halting, uneven progress convinced Congress that a more permanent measure – an Amendment – would be necessary.

Even though they maintained a numerical supermajority after the 1868 presidential election, Republicans worried that their incoming caucus would not be as ideologically unified behind black male suffrage. The lame duck session of early 1869 thus seemed the last chance to push a voting rights amendment through Congress.

Compromising between different factions of their caucus, on January 30 1869 the House Republicans passed a deliberately narrowly tailored version of the 15th Amendment primarily drafted by George Boutwell (R-MA):“the right of any citizen of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of the race, color, or previous condition of slavery of any citizen or class of citizens of the United States.” Ten days later, a broader version of the amendment passed in the Senate (typically considered the more conservative chamber). Seeking a “comprehensive, just, and … strong” statement, Senator Henry Wilson (R-MA) proposed, and the Senate passed, the following: “No discrimination shall be made in any State among the citizens of the United States in the exercise of the elected franchise, or in the right to hold office on account of race, color, nativity, property, education, or creed.” Defending the broader statement, Wilson highlighted the importance of “secur[ing] the right to vote and the right to hold office,” both keys to a government built on popular sovereignty. By eliminating additional restrictions beyond racial categories (restrictions employed throughout the United States at the time) Wilson hoped to “appeal … alike to the friends of the colored race, and to other citizens,” and indirectly, in a bold effort to expand enfranchisement, to empower states “to try … the experiment of woman suffrage.”

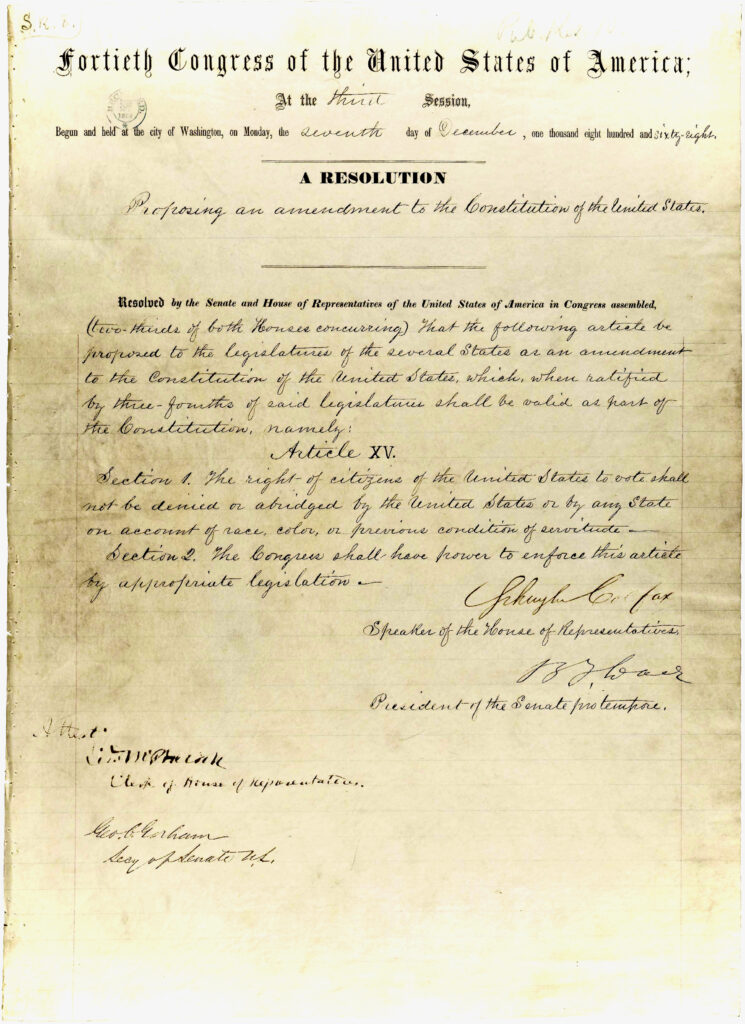

About a month before a new congress commenced in March 1869, the House and Senate convened a joint conference to reconcile the differences in their versions of the amendment. With a moderate-majority committee, and racing against time, expediency won out. With a lowest-common denominator approach, the committee adopted only the ideas shared by both versions; effectively, this meant adopting the relatively narrow House version. Fearing that the Senate additions would be impossible to ratify (or probably even to pass in the House), the conference excluded all of them. As a result, the final 15th Amendment reads like a concise edit of the House version:

Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Underscoring its continuity with the two previous Reconstruction amendments, the 15th closes with the same enforcement clause as the 13th and 14th:

Section 2. The Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

The United States had its first voting rights amendment.

In US history courses, we tend to frame voting rights amendments as affirmative grants of rights: the 15th gave black men the right to vote; the 19th gave women the right to vote; the 26th gave 18-year-olds the right to vote. Yet the difference between this framing and the actual language reveals key nuances of the federal system.

State voting systems predated the 1787 US Constitution, and that document left most voting qualifications up to the states. However, by the late 1860s the continued hopes of Reconstruction lay in the ability of freedmen to protect their rights through political power — which Southern states (and, as Republicans learned through the referendum movement, many Northerners) were committed to suppressing. So lawmakers faced a political problem: What if a state’s exercise of power (in this case, voting regulations) fundamentally violated the principles of the federal constitution?

Republicans had to balance deferring to state authority with advancing the agenda of Reconstruction. So, rather than being framed as an affirmative measure, the 15th Amendment (and each of the constitution’s subsequent suffrage amendments) is phrased as an anti–discrimination measure (“shall not be denied or abridged”). The amendment still defers to states but removes unconstitutional restrictions. In the words of then-Senator (and longtime reformer) Carl Schurz (R-MO),

States [remain] free as … ever to legislate … the free exercise of the suffrage … But … a State shall no longer have the power to swindle … citizens out of their rights. A State [may] do that which is right in its own way; but it is prohibited from doing that which is wrong in any way.

With this phrasing, the 15th Amendment established a template since relied upon to eliminate the aforementioned voting restrictions based on sex (19th) and age (26th), as well as class (the 24th Amendment’s outlawing of poll taxes uses the same construction).

Then and now, many voting rights advocates have pushed for more expansive grants of voting rights. And yet, upon passage in 1869 and ratification in 1870, the 15th Amendment was considered a dramatically transformative measure both by contemporary critics and supporters. On the opposition side, and reminding us that anti-Reconstruction attitudes were not exclusive to the South, a Connecticut broadside attacked the 15th Amendment as a violation of states’ rights, “strik[ing] at the foundation of our system of government … a gross perversion of the authority of Congress … making this a Kingdom instead of a Republic … mutilat[ing] our State Constitution.” On the other hand, Frederick Douglass celebrated the 15th by exclaiming “Never was a revolution more complete. Nothing has been left for time.” Similarly, President Grant hailed the 15th as completing “the most important event … since the nation came into life.”

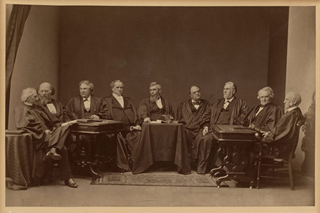

Remarkably, this transformative amendment became moot shortly after its ratification. All three branches of the federal government retreated in the face of Reconstruction’s challenges.

Judicial retreat from the 15th Amendment is best captured by two cases decided on March 27 1876: U.S. v. Reese and U.S. v. Cruikshank. In Reese, the Supreme Court applied a prohibitively narrow interpretation of the 15th Amendment that discouraged enforcement, and in Cruikshank, it invalidated the Enforcement Act designed to prosecute violations of the Reconstruction Amendments, leaving those amendments largely toothless. The next year brought the Compromise of 1877, negotiated by a bipartisan congressional commission of federal lawmakers and judges which settled the disputed presidential election of 1876 in the Republicans’ favor in exchange for ending executive enforcement of Reconstruction. Black voting rights and representation faded and ultimately cratered after a Federal Elections Bill fell to defeat in January 1891. From this point, most of the power and force of the 15th Amendment lay dormant until revived by all three branches of the federal government, in concert with activists and reformers, during the Second Reconstruction, better known as the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-20th century.

In our time voting rights and regulations remain at the forefront of our political conversations. And the questions of our time — How expansive can they be? How do they harmonize with federalism? Whose rights must be protected? How can they be enforced? — not only echo the questions of this much earlier debate of voting rights, they are a continuation of the ongoing national debate about how to politically secure a government built on popular sovereignty.

Malik Ali, a James Madison Fellow and 2017 graduate of the Master of Arts in American History and Government program, is Tukman Distinguished Teacher of History at the Branson School in Ross, California.