The Judiciary: Interview with the Author, Pt. II

Last week we spoke with Professor Joshua Dunn about a recently published document collection he edited, The Judiciary. Dunn commented on the Supreme Court’s evolving understanding of its role in our constitutional system. From the brief description of the judiciary branch given in Article III of the Constitution, the Court and observers of it have inferred its right of judicial review, that is, its power to evaluate whether actions of the legislative and executive branches of government accord with the Constitution. In more recent times, the Court has claimed a position of judicial supremacy—that it is the final arbiter of the Constitution’s meaning. This understanding of the Court’s role, Dunn said, heightens concerns about the way the Court conducts its business and the way appointments to the Court are made. It also raises questions about the conflicts that may arise when the judiciary interprets the Constitution differently from the other branches of government, or when it resolves differences between state and federal laws in favor of those that are federal. We continue this conversation today.

In the twentieth century, a debate arose over whether the Constitution carried a stable, constant meaning. People began to speak of the “living Constitution,” implying that the meaning of the Constitution changed over time. Others, calling themselves “originalists,” insisted that the Constitution should be understood to mean what those who framed the document thought it meant. Are these ideas just new terms for the older debate between those who apply a “strict construction” of the Constitution’s meaning and those who apply a looser construction?

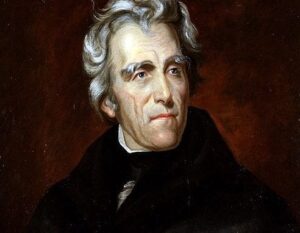

“Strict construction” and “originalism” are really different ideas, used at different times in our history. One of the earliest debates over the “strict” or “loose” construction of the Constitution arose over the creation of the First National Bank. It continued through President Andrew Jackson’s objection to an act of Congress rechartering the Second Bank of the United States. Those who voted to recharter the Bank assumed that an 1819 Supreme Court decision, McCullough v. Maryland (Document 5), had established Congress’s power to create it under the “necessary and proper” clause. Jackson disagreed, arguing that Chief Justice John Marshall too broadly construed the meaning of that clause.

Jackson’s veto message (Document 6) asserted the right and responsibility of the executive to interpret the Constitution independently of the Court. Of course, he also opposed the Bank on policy grounds. He thought the Bank gave privileges to the wealthy and to foreign stockholders at the expense of average citizens.

Twentieth-century progressives, wanting to transcend arguments over strict or loose construction, elaborated the idea of a “living Constitution.” Here, a Darwinian perspective was marshaled to support progressive legislation (although in other instances, Darwinism was used to oppose it). Progressives like Woodrow Wilson argued that the Constitution should be viewed not as a fixed framework but as a living organism, its meaning growing and changing as the nation changed. Jurists, in the words of Justice Brennan, were tasked with adapting the Constitution’s “great principles to cope with current problems and current needs” (Document 19).

Justice William O. Douglas in Griswold v. Connecticut showed how this might be done when he found a “right to privacy” implied in the Bill of Rights. He spoke of “penumbras,” or shadowy suggestions of rights emanating from the Constitution. This procedure appalled Justice Black, who called it “the natural law due process philosophy” of jurisprudence. It found guarantees of rights that would follow from the theory of natural rights throughout the Constitution—and yet nowhere in particular.

Countering such views, President Reagan’s Attorney General, Edwin Meese (Document 18), outlined a “Jurisprudence of Original Intention.” Its aim, he said, was “to judge policies in light of principles, rather than remold principles in light of policies.” Jurists should interpret the actual word of the Constitution, keeping in mind the framers’ understanding of those words.

To Justice William Brennan (Document 19), the originalist approach amounted to “arrogance cloaked in humility,” because, he said, it presumed to know what the framers actually meant. Brennan claimed that “sources of potential enlightenment such as records of the ratification debates provide sparse or ambiguous evidence of the original intention” of the framers. And yet the debate over the ratification of the Constitution is one of the most well-documented debates in history—we have the 85 essays of The Federalist that detail the thinking of the framers as well as the numerous Antifederalist essays to which The Federalist responded. We also have records of the debates in the state ratifying conventions. For originalists today, those debates are often the most important source of information, because they represent the will of the people as exercised through their elected representatives to those conventions. Also, much of the time the debate over ratification concerned not what the Constitution meant but rather whether it was a good idea.

Granted, there are places in the Constitution where the meaning remains opaque. Some people make much of the vesting clause of Article II, contrasting it with the use of the phrase “herein granted” in Article I. From this difference, they infer that the framers meant to limit the power of Congress to those specifically enumerated and that they meant to give the executive larger, less specific authority. Whether the wording really supports that interpretation is debatable. Still, there is often quite substantial evidence about what the ratifiers understood the Constitution to mean.

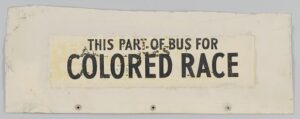

Brennan’s real objection to originalism was that the founders’ struggle for freedom differed from the struggles of later Americans. The current generation found threats to their rights not in government but in economic forces and majority prejudices. Still, Brennan said, the overarching aim of the Constitution was to protect “the human dignity of every individual.” This aim could not be doubted, since successive generations’ amendments to the Constitution had only broadened its power to safeguard human dignity.

Antonin Scalia, the most outspoken defender of originalism in recent times, disagreed; he did not see Constitutional jurisprudence marching steadily toward the expansion of such safeguards (Document 21). He called non-originalism “a two-way street that handles traffic both to and from individual rights.” Besides, untethering judicial opinion from inquiry into the founders’ intent undermined the court’s legitimacy. If jurists were not guided by the intentions of those who wrote the Constitution and gave them their authority, how could they justify their role?

It’s interesting that in recent years, even many liberal justices and scholars have declared themselves originalists. They have seen that their claims for the “living constitution” can work out to their disadvantage if there are five justices on the Court who disagree with their policy views. As Elena Kagan said, “We’re all originalists now.”

Yet the last document in your collection seems to make a conservative argument for a more expansive reading of the powers of government to regulate individual behavior.

Yes, we live in interesting times. Harvard Law School Professor Adrian Vermeule (Document 28) recommends what he calls “common-good constitutionalism.” He echoes the language Brennan used, arguing for a reading of the Constitution that empowers the government to rule in the best interests of the nation as a whole. “The sweeping generalities and famous ambiguities of our Constitution,” he says, “afford ample space for substantive moral readings that promote peace, justice, abundance, health, and safety, by means of just authority, hierarchy, solidarity, and subsidiarity.” Vermeule reads the Constitution as supportive of organized labor in confrontations with corporate interests, government initiatives to protect the environment, and even vaccine mandates. But he does not believe the Constitution protects abortion, the Court’s current expansive reading of freedom of speech, or “sexual liberties.” His essay has been condemned on the right for threatening America’s founding principles and on the left for proposing “authoritarian extremism.” What is most interesting, though, is that if you accept Brennan’s position on constitutional interpretation, it is very difficult to construct a principled objection to Vermeule’s argument. You can disagree with it on policy grounds either from the right or the left. But if you accept that justices are authorized to give expansive interpretations of particular parts of the Constitution, those interpretations do not have to go in a particular direction.

Along with our other Core Document Collection volumes, The Judiciary is available in our online bookstore, as both a hard copy and an ebook.