The Return of the Taliban

We know this story: A charismatic leader drew followers by preaching about the need for a return to a purer form of Islam. The followers came to be called Taliban, the Arabic word for “students.” They intended to do more than set an example. They formed a fighting force, drawing additional recruits from various Islamic brotherhoods and tribal groupings. Slowly they exerted their authority over a larger area, forbidding practices they considered pagan or un-Islamic. No alcohol, of course, but also no tobacco or dancing. Eventually, the Taliban confronted and fought the westerners who themselves were expanding the area under their control. The leader of the Taliban declared a jihad against the foreigners. The fight went on inconclusively, but eventually the westerners gained control.

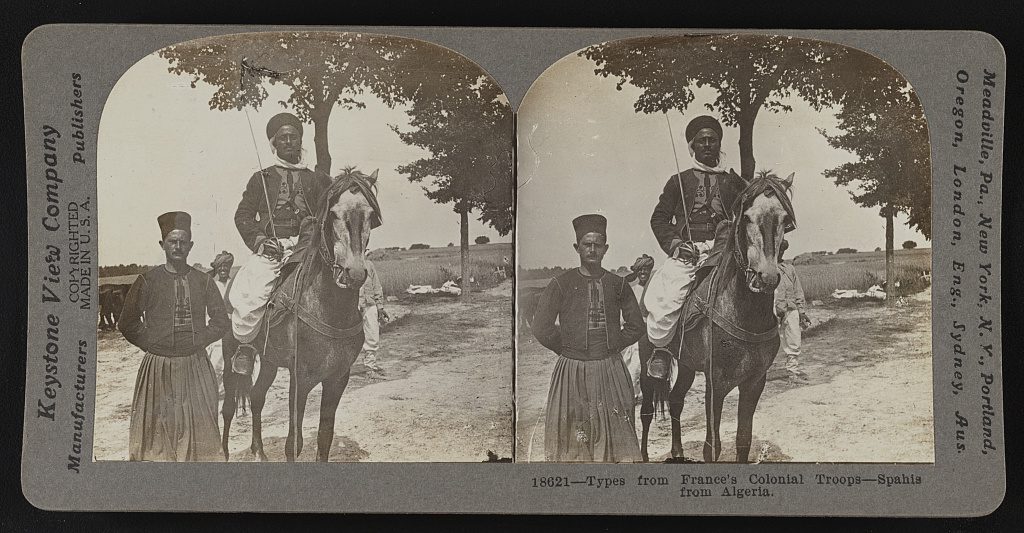

We know this story, but it is an earlier version of the story we are most familiar with. Briefly told, it is the story of Umar Tal and the Taliban of western Africa in the nineteenth century. The westerners were the French, expanding from their base in Algeria, which they invaded in 1830. Even though the French gained control of north and west Africa, resistance to their rule in Algeria continued, with occasional rioting and everyday acts of resistance, as well as larger more organized conflicts in 1864, 1871, and 1881. In desert areas, resistance continued until the 1920s. After World War II, during which the Allies, including the French, at the insistence of the United States, promised self-determination to subject peoples, resistance returned. It grew into a rebellion that eventually drove the French from Algeria. Islam was important in this successful rebellion, especially among the rank and file of the National Liberation Front (FNL, in its French initials), who drove out the French. This Islamic component of the resistance became especially evident in the 1990s, as Islamic groups revived to fight the Algerian government, as the FNL had once fought the French.

The French invaded Algeria for gain; to spread Christianity; to defend their honor, supposedly insulted by an Algerian leader; and to distract themselves from some domestic problems. The violence they used was not much different in kind or quantity from what the British and Americans used elsewhere. Eventually, however, the same humanitarian impulse that led to the end of the slave trade, and then slavery itself, also led to the end of enforced control of extra-national territory—to the end of imperialism. It no longer made sense to European and American publics to use force to sustain a supposedly civilizing or modernizing mission. And by that point, it seemed no longer necessary. European and American ideas, culture, and commerce already dominated the world.

So accustomed are we to our modern way of life, to the ideas, culture, and commerce that now dominate the world, that we no longer appreciate how different this life is from the way humans lived for thousands of years before the American Revolution began to transform the world. Nor do we always grasp how threatening this revolution is to many, especially among the traditionally devout. We might argue that what is threatened is merely worldly power (especially power over others, including women); things truly of God cannot be threatened by mere human ideas and actions. But Islam, like Judaism, although moored in the eternal, is a religion of law, and thus emphatically political and of this world.

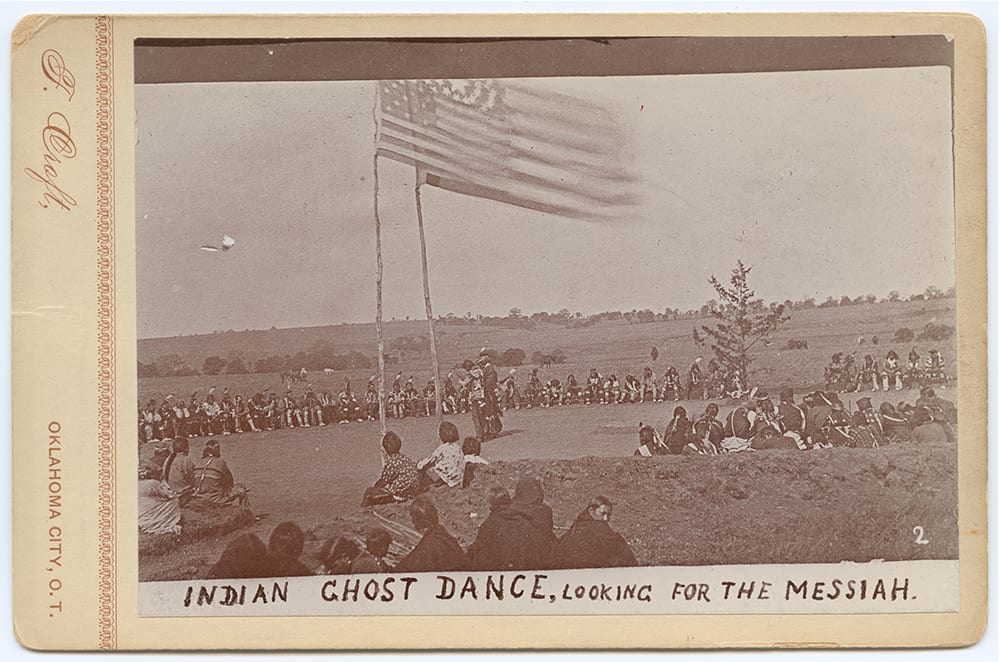

In the face of the modern revolution, some have resisted by returning to what they claim are traditional ways of life, but are often new and innovative practices. For example, as our own country’s westward expansion across North America brought the traditional Indian way of life to an end, a new innovative religion, the Ghost Dance, spread among various Indian tribes. It preached that the Indians could save themselves by reviving their traditional ways. Among the Sioux, it encouraged militant resistance to American settlers and the military that protected them. In the midst of this resistance, the young Sioux Tasunka shot and killed Lieutenant Edward Casey. Tasunka, who was about the age of those who flew the planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, had been educated at the Indian school at Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He fully expected to be captured and executed for the murder of Casey. At his trial, Tasunka is reported to have said:

I am an Indian. Five years I attended Carlisle and was educated in the ways of the white man. When I returned to my people I was an outcast among them. I was no longer an Indian. I was not a white man. I was lonely. I shot the lieutenant so I might make a place for myself among my people. Now I am one of them. I shall be hung and the Indians will bury me as a warrior. They will be proud of me. I am satisfied.

Many students of Islamist movements have concluded that those who join these movements share motives similar to those of Tasunka. They are often second-generation Europeans or Americans, caught between the traditional life of their parents and the modern life around them that they are not fully part of. In areas of the world like Afghanistan, where modern life still contends with traditional ways, Islam provides, as it did from the beginning of its confrontation with western imperial power, another important justification for and means of resistance to this power.

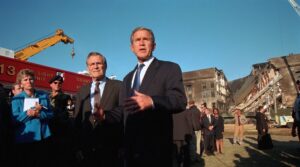

To recognize the effect of the modern or western revolution on the world, and on Islam, is neither to assign blame nor to excuse. It is only to offer a way of understanding why the Taliban return and why they may continue to return in various forms for years to come. We might hope better understanding will lead to more effective ways of dealing with such movements. But to elevate human understanding in this way is, of course, a western practice.

David Tucker is the general editor of Teaching American History’s core document volumes. He is the author most recently of United States Special Operations Forces (2020) and Revolution and Resistance: Moral Revolution, Military Might, and the End of Empire (2016). This post draws on arguments in the latter.