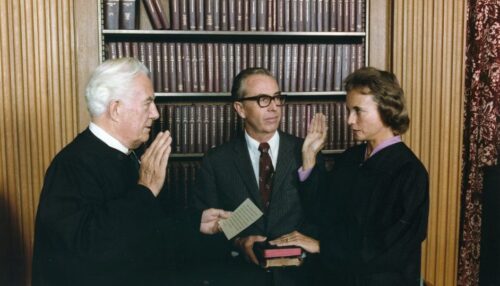

Sandra Day O'Connor: FWOTSC

This month, in the spirit of our Core Document volume Gender and Equality, we are highlighting women’s achievements in American history. Today is the 40th anniversary of Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s nomination to the Supreme Court. The first female to sit on the highest court of the land, Justice O’Connor served a 25-year term, retiring in 2006. She is remembered for her pragmatic jurisprudence, as well as her recognition of the importance of federalism when defining the role of the federal government.

“I come to you tonight wearing my bra and my wedding ring.” So began many of Justice O’Connor’s speeches. Intending to disavow herself of feminism, she still savored her role as the FWOTSC, or the First Woman on the Supreme Court. Furthermore, as a victim of gender discrimination, she was patently aware of the difficulties women faced within the professional world. In response, she chose to advance the fight for gender equality within the professional, as opposed to cultural, arena.

Just as she disagreed with second wave feminists regarding the cultural symbols of female oppression, she disagreed with third wave feminists arguing that a woman’s experience, and therefore her voice, differed from a man’s. Calling such a view “troubling . . . because it so nearly echoes the Victorian myth of the ‘True Woman’ that kept women out of law for so long,” O’Connor found gender politics to be harmful to both women and society. She neatly encapsulated her worldview in her oft-repeated maxim: “A wise old man and a wise old woman reach the same conclusion.” This view set her clearly at odds with later female justices such as Sonia Sotomayor, who famously eschewed such gender and ethnic impartiality as “aspirational” and asserted that “a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would . . . reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn’t lived that life.”

Born to an Arizona ranch family, Sandra Day was one of the first women to be educated at Stanford’s school of law. Despite graduating in the top 10% of her class, the only job offers she received after passing the California Bar were for legal secretary positions. Accordingly, her early professional years were spent partly in private practice and partly as a government lawyer. Thanks to her political connections, she was appointed to the Arizona Senate in 1969. Serving two terms, she rose to the rank of Majority Leader, becoming the first woman to serve in that role. After her retirement from politics, O’Connor became a judge, first serving in Maricopa County and then in the Arizona State Court of Appeals. A mighty force in Arizona’s state politics, Sandra Day O’Connor was a fervent supporter of Barry Goldwater’s and an early advocate for Ronald Reagan during his 1980 presidential campaign. Along the way, she and her husband John managed to raise three children.

During his candidacy, Reagan pledged to nominate a woman to the bench. His opportunity arrived shortly after his inauguration, when Associate Justice Potter Stewart announced his retirement. While there was a pool of qualified and brilliant female federal judges, they were largely liberals, and not viable options for a Reagan administration determined to nominate judges whose conservative philosophies would rein in what was perceived to be the Warren Court’s judicial overreach. Social conservatives wanted a nominee with strong anti-abortion credentials. Reagan prioritized a judicial philosophy of restraint and a smooth and successful confirmation process. O’Connor’s Republican credentials, western upbringing, judicial and legislative background, and brilliant career at Stanford (where she was an esteemed classmate and love interest of then-Associate Justice Rehnquist’s) made her a natural fit for Reagan and a palatable nominee for social conservatives. On September 21, 1981, the Senate voted 99-0 to confirm Sandra Day O’Connor as the first female Supreme Court justice.

It was expected that O’Connor would join the growing conservative block of Chief Justice Warren Burger, Justice Rehnquist, and Justice White. However, O’Connor served more as a centrist judge; while she was a firm proponent of federalism, her pragmatic view of the Constitution was a greater influence on her votes than conservative ideology. Eschewing Justice Scalia’s later philosophy of originalism and “bright lines,” Justice O’Connor found too much grey area in constitutional interpretation to rely on one specific philosophy. A firm believer in incrementalism, she felt that justices should simultaneously adhere to the doctrine of stare decisis (abide by precedent) and afford state legislative bodies as much freedom as was constitutionally permissible.

Justice O’Connor’s pragmatism and incrementalism are exemplified through her decisions regarding the Establishment Clause in Lynch v. Donnelly and abortion in Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Rights and Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

Colloquially referred to as “the reindeer rule,” O’Connor’s concurrence in Lynch v. Donnelly (1984) differed significantly from Chief Justice Burger’s majority opinion. While both found a publicly funded creche to be permissible under the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, Burger argued that the creche advanced Christianity in an “indirect, remote and incidental way,” which fell short of government endorsement of religion. Justices Brennan, Marshall, Blackmun and Stevens dissented vehemently, contending that the creche’s inclusion in civic activities was a “coercive, though perhaps small, step toward establishing the sectarian preferences of the majority at the expense of the minority.” Refusing to engage in the theoretical debate of “how much religion is too much religion?” O’Connor side-stepped the issue. She reasoned that the combination of Christian symbology with the cultural symbols of Santa Claus and his reindeers made the creche constitutionally permissible. Calling the decorations ubiquitous, she wrote “The display of the creche . . . serves a secular purpose — celebration of a public holiday with traditional symbols. It cannot be fairly understood to convey a message of government endorsement of religion.”

O’Connor’s impact on abortion case law is more profound. While she personally found abortion “abhorrent” and condemned Justice Powell’s trimester scheme in Roe v. Wade, she was hesitant to violate stare decisis and overturn the decision. Rather, her opinions throughout the 1980s and 1990s embraced a subtler shift in jurisprudence. Instead of adopting Roe’s view of abortion as a right under the 14th Amendment that required “strict scrutiny” of state interference by the Court, she relied on the “undue burden” standard. First articulated in her dissent in Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health (1983), O’Connor argued for the state’s legitimate interest in regulating abortion as long as the regulation did not place an undue burden on an abortion-seeker. Nearly a decade later, this reasoning formed the core argument of the majority opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992). Writing in a 5-4 decision, Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter ruled that the doctrine of stare decisis required that Roe v. Wade’s essential holding be upheld. However, they found that the state did have a compelling interest in regulating abortion, writing:

The fact that a law which serves a valid purpose, one not designed to strike at the right itself, has the incidental effect of making it more difficult or more expensive to procure an abortion cannot be enough to invalidate it. Only where state regulation imposes an undue burden on a woman’s ability to make this decision does the power of the State reach into the heart of the liberty protected by the Due Process Clause.

Justice O’Connor’s lack of dogma made her a centrist — and a possible swing vote for nearly every case that came before the Supreme Court during her tenure. So powerful was the FWOTSC that the Supreme Court came to be known as the “O’Connor Court.” As the “George Washington” of female Supreme Court justices, she was a powerful voice for pragmatism in constitutional jurisprudence and gender equality.

Sources

Teaching American History webinar on Sandra Day O’Connor

Thomas, Evan. First: Sandra Day O’Connor (Random House: New York, 2019).

O’Connor, Sandra Day. “Portia’s Progress.” Speech, New York University Law School, October 29, 1991. Archives of Women’s Political Communication. https://awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu/2017/03/09/portia%C2%92s-progress-oct-29-1991/

Sotomayor, Sonia. “A Latina Judge’s Voice.” Speech, October 26, 2001. In Gender and Equality, ed. Sarah A. Morgan Smith (Ashbrook Press: Ashland, OH, 2020).

Lynch v. Donnelly, 465 U.S. 668 (1984)

Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health, 462 U.S. 416 (1983)

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992)