The Right of the Disenfranchised to Petition

The First Amendment protects five distinct freedoms: religious freedom, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and freedom to petition. When asked to list these freedoms, most students omit the last, because it is so little regarded in our own time in comparison with the others. In antebellum America, however, the right to petition was once among the most controversial of these protected freedoms, because it was a political right belonging to all the people—and not simply to voters. Petitions allowed even the disenfranchised to participate in the political system; because petitions were explicitly linked to the “redress of grievances,” they carried an innate recognition that nonvoters had interests and even rights that the government was obligated to respect. Because petitions were also by nature a relatively passive means of political engagement (and were often couched in the language of “requests” for consideration or privilege rather than “demands” of rights), they were also considered to be a perfect vehicle for women’s political expression.

Until the 1820s, women’s petitions were most commonly directed at state and local governments, but the issue of Indian removal under Andrew Jackson’s administration inspired reformers like Catharine Beecher to turn their efforts to petitioning Congress. Beecher was recruited by Jeremiah Evarts, the secretary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), to draft an appeal to the women of America on behalf of the Cherokee and other southeastern tribes. The letter was what is known as a “circular” because it was meant to be circulated among Beecher’s friends and then forwarded to their circles of influence, and so on.

Beecher argued that because women were the traditional keepers of private (and by extension, public) morality, they had a duty to speak against the injustice being done by the government. Sagely, she urged women to counsel their political representatives to uphold what was right as a matter of their own self-interest. Like the Biblical heroine Esther, she argued that if American women hesitated to take up the cause of the oppressed, they would be justly subject to divine punishment. By speaking, in contrast, even in the unprecedented national forum of petitioning Congress, they might yet ensure that they and their loved ones “may be saved from the awful curses denounced on all who oppress the poor and needy, by Him, whose anger is to be dreaded more than the wrath of man.”

As with earlier petitions to state and local governments, those inspired by Beecher’s Circular were relatively cautious in asserting a role for women in public discourse, framing all criticism in terms of traditional gender roles and a feminine duty to see to the needs of the poor and oppressed. Women continued to petition at the federal level throughout the next decade, applying a similar logic to the odious subject of slavery.

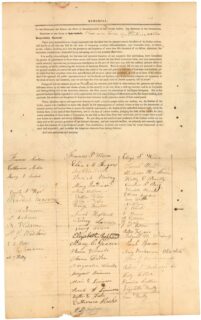

A particularly striking example of the connection between freedom of petition and the rights of the disenfranchised occurred after Texas declared independence from Mexico in 1836, talks of annexation immediately followed, but were slowed by existing treaties with Mexico. During Congress’ first series of debates over the annexation of Texas in 1838, John Quincy Adams (1767–1848) attempted to present petitions signed by roughly four hundred women from Massachusetts against the admission of another slave state. Another congressman commented that he “considered it discreditable” for women to attempt to extend their political influence beyond their own households. Adams—whose mother had famously urged that the new nation ‘remember the ladies’ when carving out protections for personal rights and freedoms—refused to let such a comment stand. Over the next three weeks, he delivered a series of speeches addressing the question of women’s role in political life. Weaving together examples from the ancient world to the American Revolution, Adams’ argument highlights women’s essential public role in republican societies, as voices in the mix of democratic discussions, shaping policy even without formal electoral privileges.

Read more about women’s informal political activism through the power of petition in these documents from our forthcoming collection on Gender and Equality:

[Catharine Beecher], CIRCULAR: Addressed to Benevolent Ladies of the United States (December 1829)

John Quincy Adams, “The Right of the People, Men and Women, to Petition,” June 16–July 7, 1838