The Whiskey Rebellion

President George Washington and Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton stepped into a carriage on Market Street on September 30, 1794, to begin a journey west of Philadelphia, then the new nation’s seat of government. They were not embarked on a sightseeing tour of the countryside, nor were they on a mere political fence-mending mission. Indeed, in President Washington’s eyes and those of Hamilton, his most trusted aide, this trip was as vital to the new nation’s survival as their journey to Yorktown, VA, thirteen years earlier. The American army defeated Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown—thus ensuring independence. This time Washington would assume command of a large militia force from New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia waiting for his arrival in Carlisle, PA. His goal was to defeat the gravest domestic insurrection in the United States prior to the Civil War.

Known as the Whiskey Rebellion, the insurrection began in western Pennsylvania yet spread into other states in the summer of 1794. The rebels were farmers angered by a federal excise tax on distilled liquors—the first direct tax on a domestic product in the nation’s history. Treasury Secretary Hamilton proposed the tax to raise the revenue needed to pay the interest on government bonds purchased by wealthy investors. Hamilton believed that tying elite support to the new government would stabilize United States credit and earn the loyalty of those who bought the bonds. In Hamilton’s view the tax—which became the second highest source of revenue for the new republic—was a necessary component of his plan.

Farmers in the backcountry saw the tax as an assault on their livelihood because it was easier and more profitable for farmers to convert their grain to whiskey before transporting it for sale to thirsty patrons in eastern markets. There was high demand for whiskey in early America. In the 1790s, Americans consumed nearly 6 gallons of alcohol per year, compared to just over 2 gallons today. Whiskey was almost the only source of ready cash in the nation’s western regions and was a substitute for currency in many cases.

Some Americans see the American founding as inevitable. This view holds that British colonists in North America were destined for independence; that when they rebelled against the King and Parliament’s tyrannical rule and wrote a constitution enshrining liberty and equality for all, they won the unwavering gratitude and allegiance of all citizens of the new republic, including the citizens in what is today western Pennsylvania and Ohio—regions considered backcountry in the 1790s. The Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 contradicts this myth.

The Pennsylvania farmers supplying the uprising’s energy did not possess a high degree of allegiance to the new American government. In an age of poor roads and slow communication, Philadelphia seemed remote to the Ohio River Valley settlers, just as London did to Philadelphians two decades earlier. To those on the frontier, America’s governing class seemed as unfamiliar with their needs as Parliament had been in the 1760s. The frontiersmen compared the new tax to those Parliament imposed on the British colonies during the imperial crisis of the 1760s. How could Philadelphia govern the backcountry any better than London had Philadelphia? Some argued for alliances with Spain or revolutionary France if the federal government did not rescind the tax. There was a genuine chance the Union would split—East vs. West—after only a half a decade under the new Constitution. Washington feared that “the mere touch of a feather” would push westerners to dissolve the Union.

Hamilton urged President Washington to take the insurrectionists seriously. In a lengthy memorandum to Washington, Hamilton acknowledged that the opposition had “first manifested itself in the milder shape of the circulation of opinions.” Now, he told the president, “resistance . . . was more inclined to practice” violence (Document B). Hamilton argued that “Whenever the government appears in arms, it ought to appear like a Hercules and inspire respect by the display of strength.” He hoped that by playing the militia card, the government would avoid bloodshed while enforcing the law.

The evidence supports Hamilton’s thinking. In the words of historian Jay Wink, the farmers “did far more than refuse to pay the infernal whiskey tax.” Excisemen found themselves targets of musket balls, victims of tarring and feathering, and arson victims when the rebels burned their homes and businesses. Insurgents raised liberty poles to rally support, endorsed aggressive petitions, and established committees of correspondence to spread the word of their discontent. They destroyed the stills of neighbors who paid the tax. In short, they conducted themselves in the same manner that the American colonists did when resisting Parliament’s taxes. The whiskey rebels’ attitude is vividly displayed in the political cartoon and poem, An Exciseman (Document A). The cartoon depicts a tax collector threatened with tarring and feathering before being hung over a barrel of whiskey that is set ablaze. To the rebels, they were the warriors who fought a revolution against a government imposing taxes unjustly. Their rebellion was a natural extension of the logic of the American Revolution.

When Hamilton notified the president that Pennsylvania judges were failing to enforce penalties for those who refused to pay, Washington decided it was time to act. ” Laws,” he said, could not “be trampled with impunity” for if “a minority … is to dictate to a majority, there is an end put at one stroke to republican government” (Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, p 718). In a proclamation dated August 7, 1794, Washington accused the insurrectionists of “inflicting cruel and humiliating punishments upon private citizens for no other cause than that of appearing to be friends of the laws.” They were “armed banditti disguised . . . to escape discovery” (Document C). Washington called forth the militia to put down the rebellion and decided to take command himself—the only time a president as commander-in-chief has done so. Washington combined this impressive show of force with an offer of amnesty to the rebels in exchange for an agreement to submit to the tax—perhaps in recognition that many of the disgruntled farmers had fought with him during the Revolutionary War.

The controversies surrounding the rebellion did not immediately fade away. In fact, the events contributed to the beginnings of the first party system in the United States. Washington blamed the newly formed Democratic Societies for fomenting insurrection, a charge offensive to Republican leaders Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Jefferson, who had warned Washington that the tax “would be seen as odious”, viewed “Hamilton’s Insurrection,” as “an inexcusable aggression against people at the ploughs.” James Madison saw it as a pretense for maintaining a standing army, an outcome feared by the founding generation because of its association with the standing armies of kings. Jefferson pledged to repeal the tax when he became president, no doubt winning the favor of whiskey drinkers everywhere.

The documents in ourCore Document Collection, Chapter 8: The Whiskey Rebellion from Volume I of Documents and Debates in American History illustrate fundamental differences in the early republic over the federal government’s power to tax its citizens, regulate commerce, and exercise executive power in an emergency. The Whiskey Rebellion debate foreshadowed similar constitutional debates in American history, including the Nullification Crisis of the 1830s and the expansion of Congressional commerce power in the twentieth century.

Each chapter in the Documents and Debates two-volume collection includes Study Questions that ask students to make connections between events in United States history. This chapter’s Study Questions invite students to compare the economic controversy that culminated in the Whiskey Rebellion to those that led to the Hartford Convention and the Nullification Crisis. The questions also ask students to compare Washington’s use of executive power with Lincoln’s call for peace in his First Inaugural.

Documents in this chapter include:

- Anonymous, An Exciseman, c. 1791

- Alexander Hamilton to George Washington, “The Disagreeable Crisis in the Western Counties,” August 5, 1794

- George Washington, Whiskey Rebellion Proclamation, August 7, 1794

- (Alexander Hamilton), Tully Essays, August 23, 26, 28 and September 2, 1794

- William Findley, Defense of the Insurgents, 1796

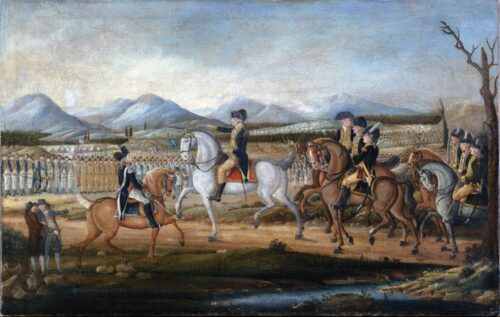

- Washington Reviewing the Western Army at Fort Cumberland, Maryland, oil on canvas, c. 1795, attributed to Frederick Kemmelmeyer

We have also provided audio recordings of the chapter’s Introduction,

Documents, and Study Questions. These recordings support literacy development for struggling readers and the comprehension of challenging text for all students.

Teaching American History’s We the Teachers blog will feature Documents and Debates with their accompanying audio recordings each month until recordings of all 29 chapters are complete. In today’s post, we feature Volume I, Chapter 8: The Whiskey Rebellion. On January 26, we will highlight Volume II, Chapter 22: The New Deal: Social Security. We invite you to follow this blog closely so you will be able to take advantage of this new feature as the recordings become available.