Introduction

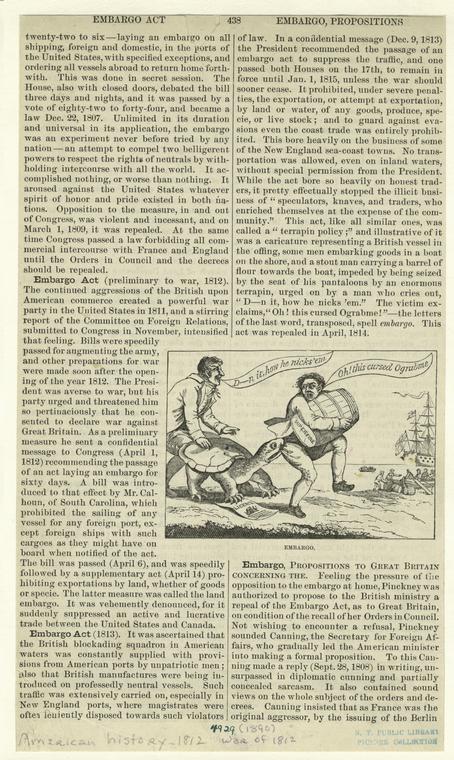

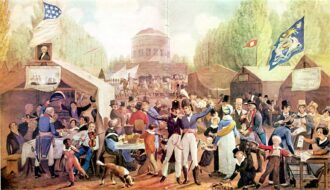

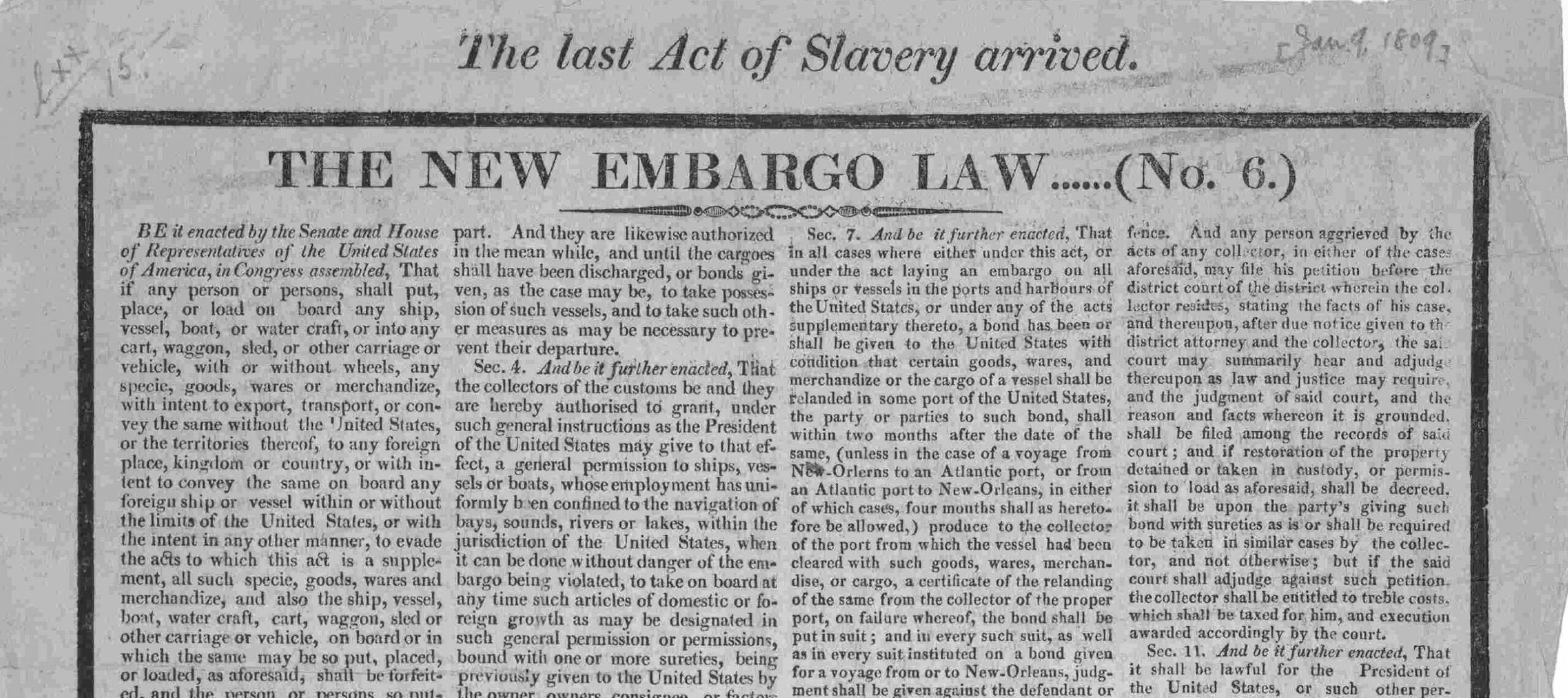

In 1791, the first Congress passed an excise tax on distilled alcohol, the first tax ever levied by the national government on a domestic manufacture. Farmers in the nation’s frontier counties (who commonly turned much of their grain crop into whiskey for easier transportation to eastern markets) bore the brunt of the tax and rapidly made their dissatisfaction with the policy known. Resistance was best organized in the four western counties of Pennsylvania, whose residents held a series of public meetings to draft petitions urging their representatives to repeal the law. At the same time, these meetings adopted resolutions advising individual non-compliance with the law, framing it as an unjust imposition upon the liberties of the people.

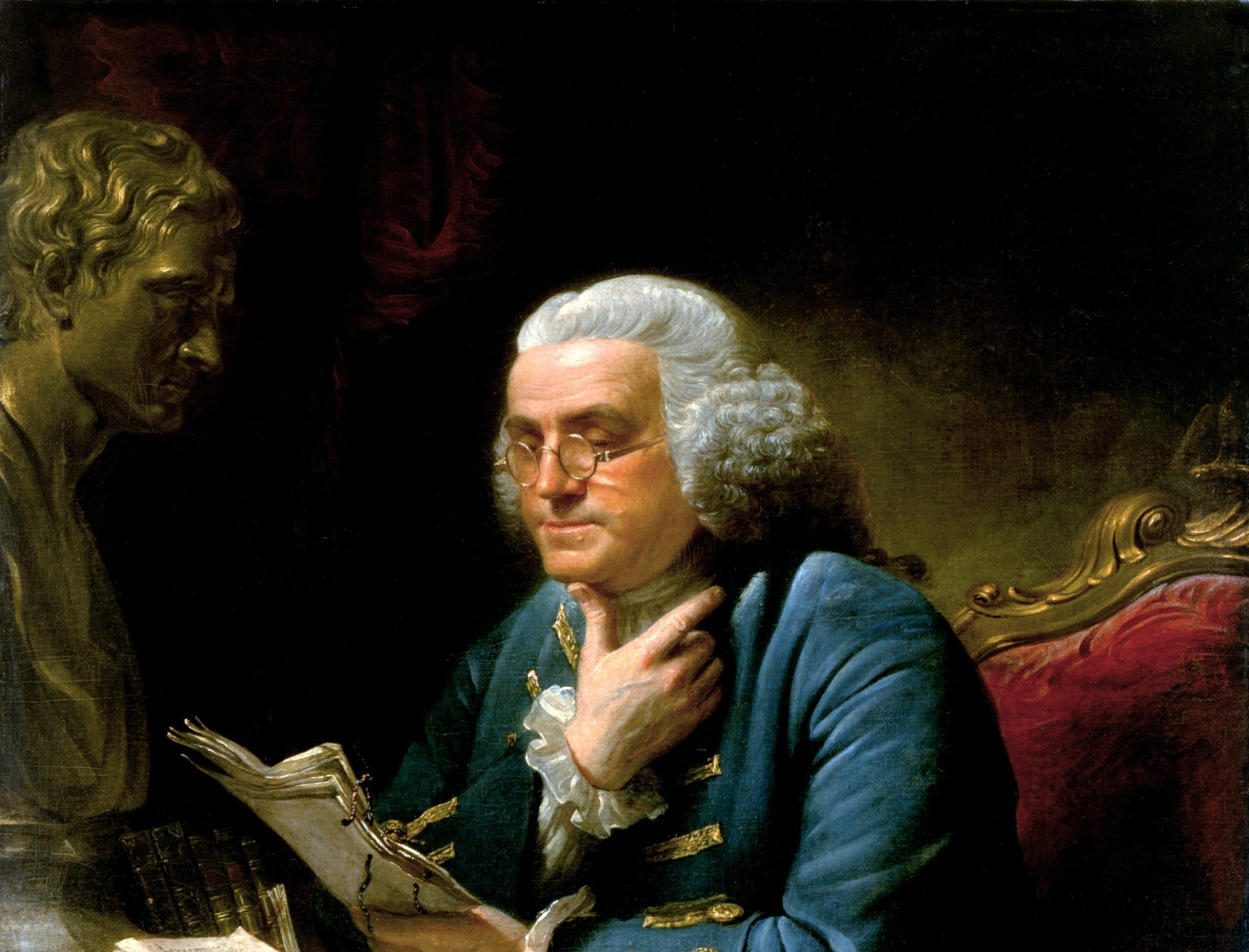

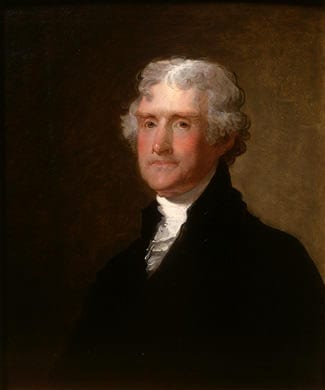

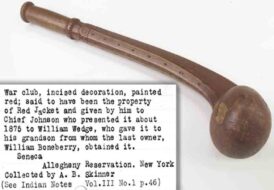

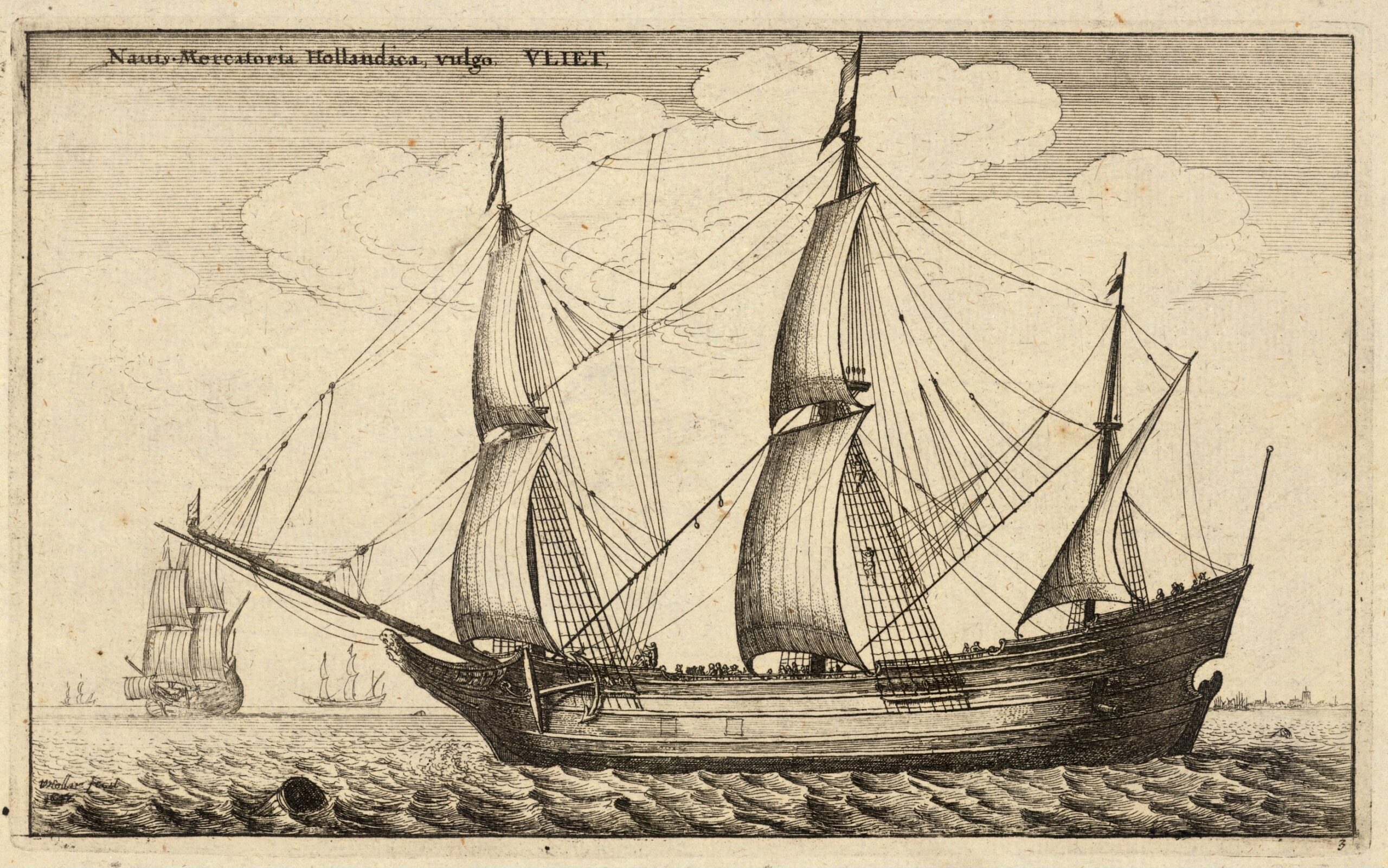

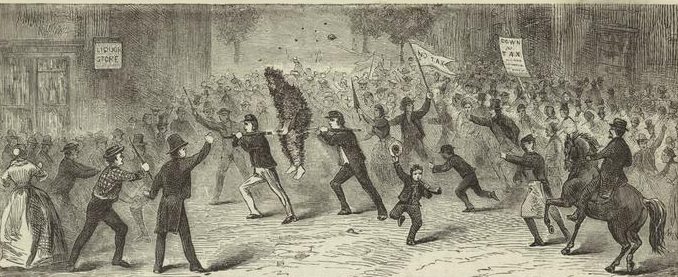

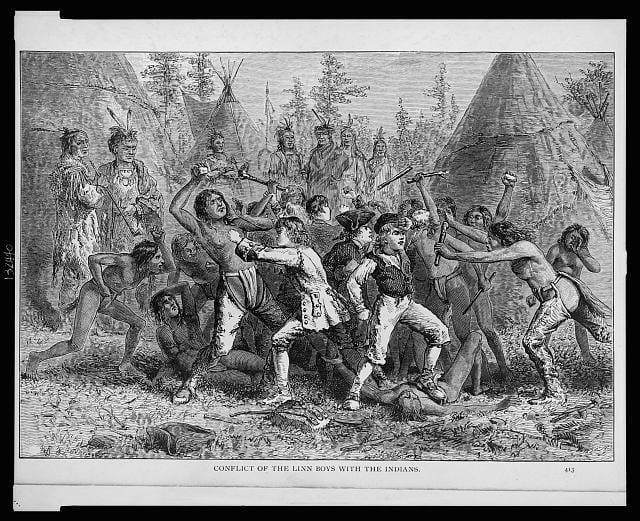

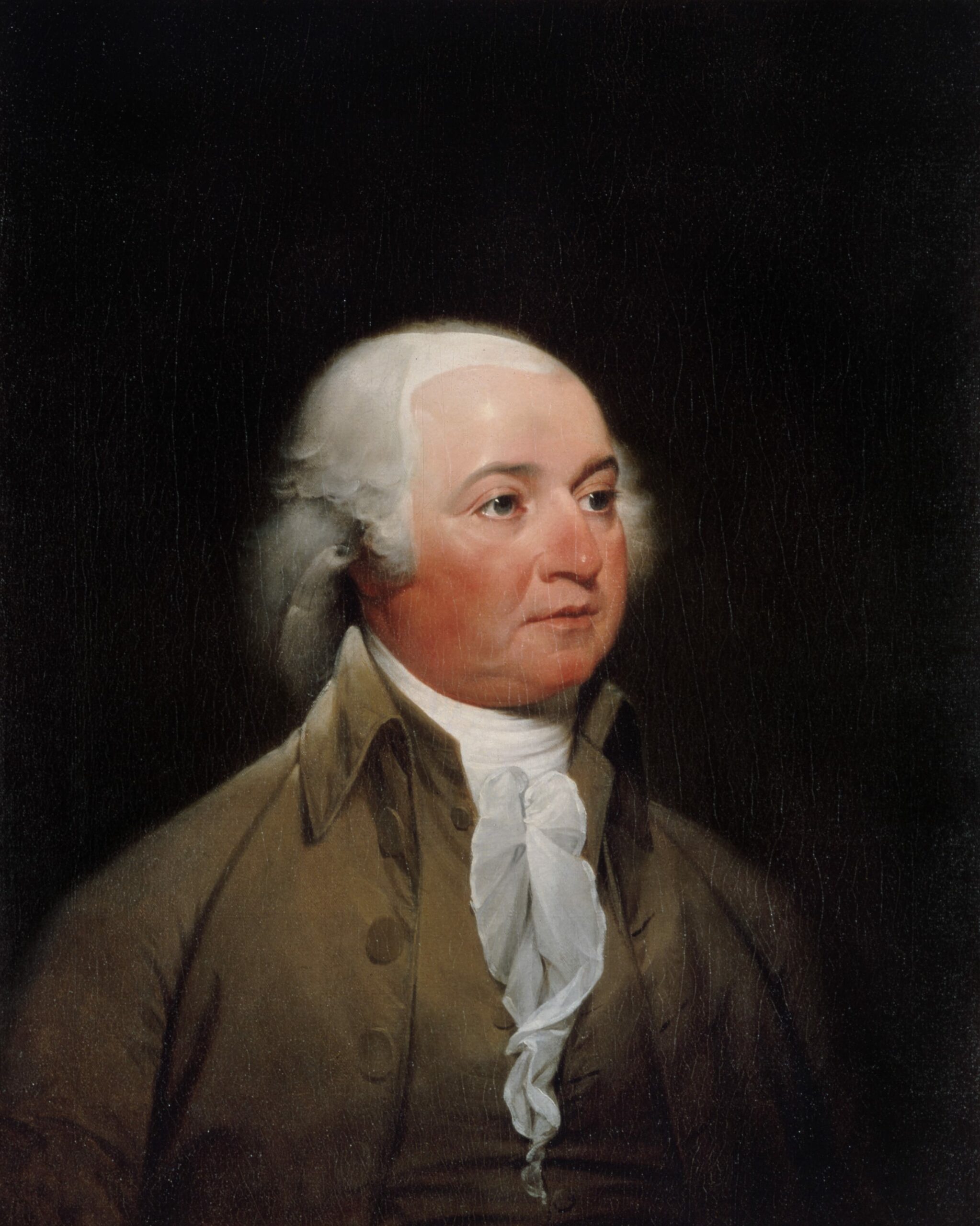

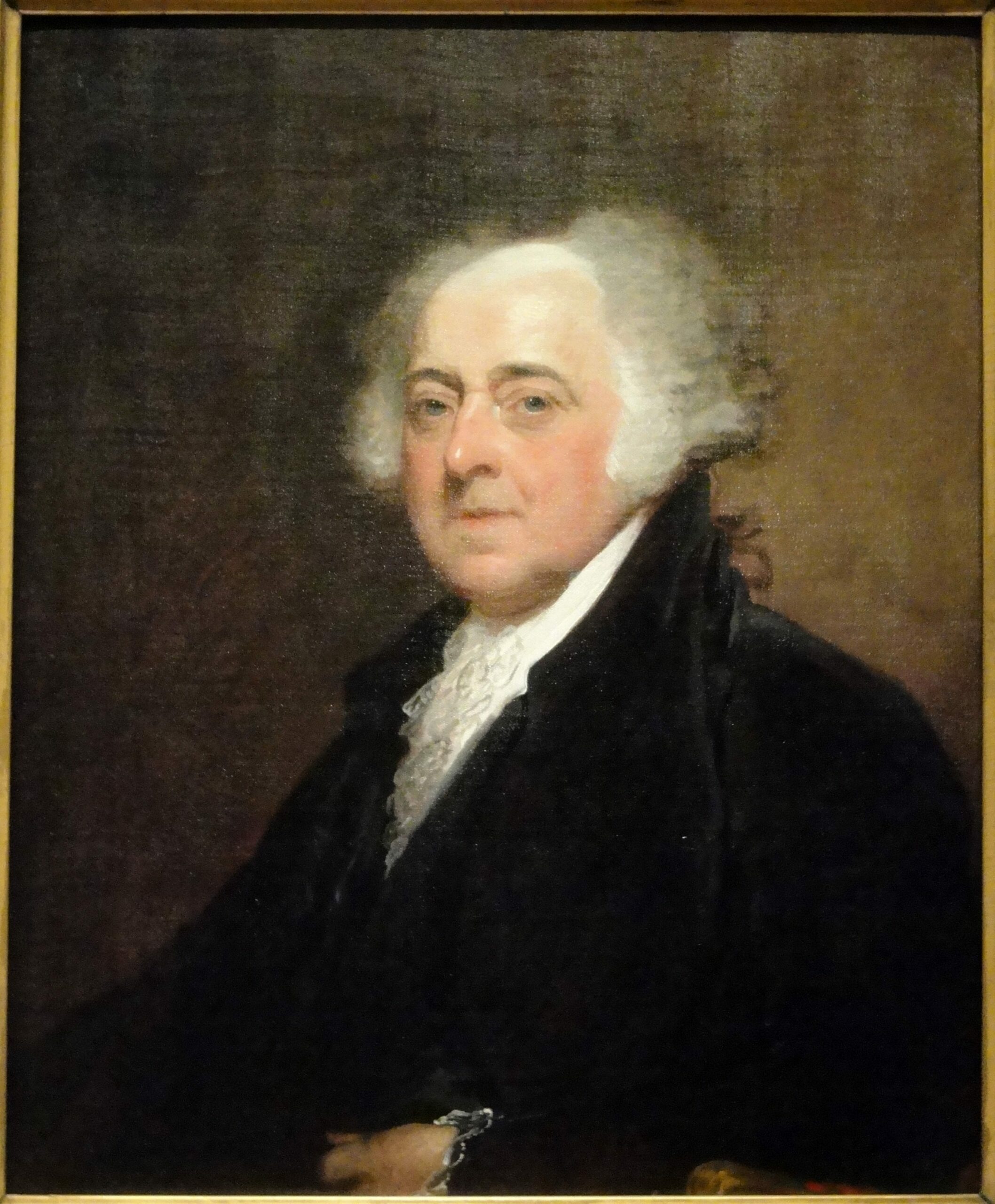

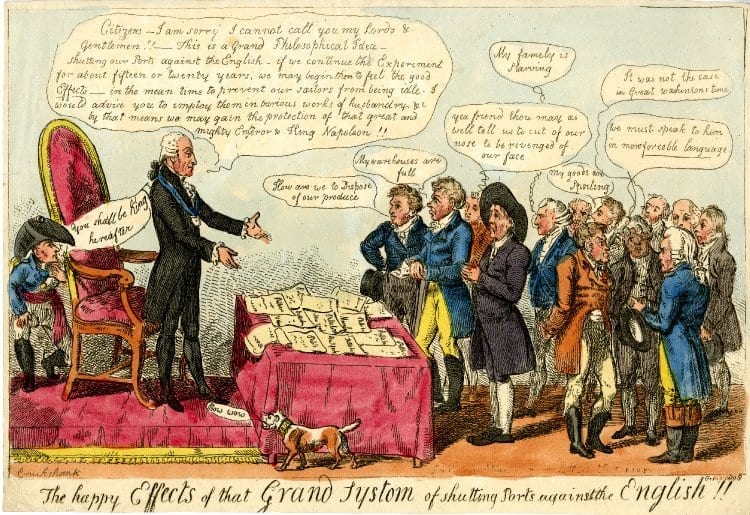

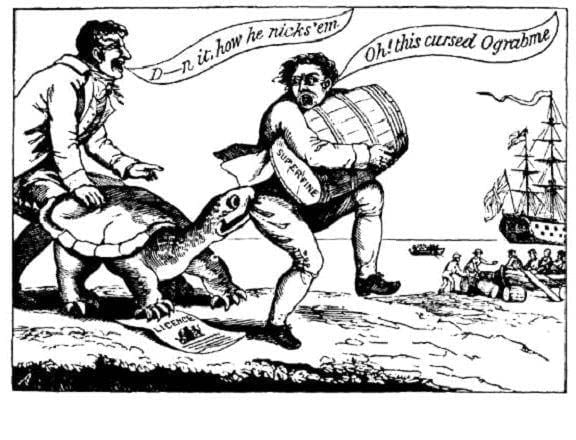

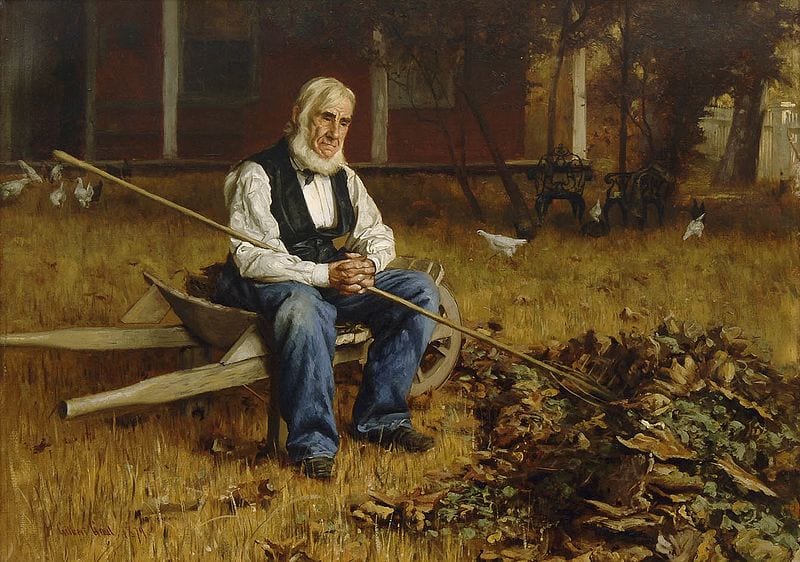

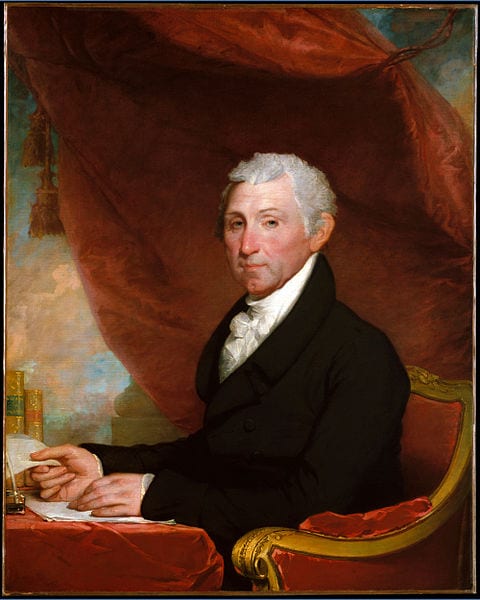

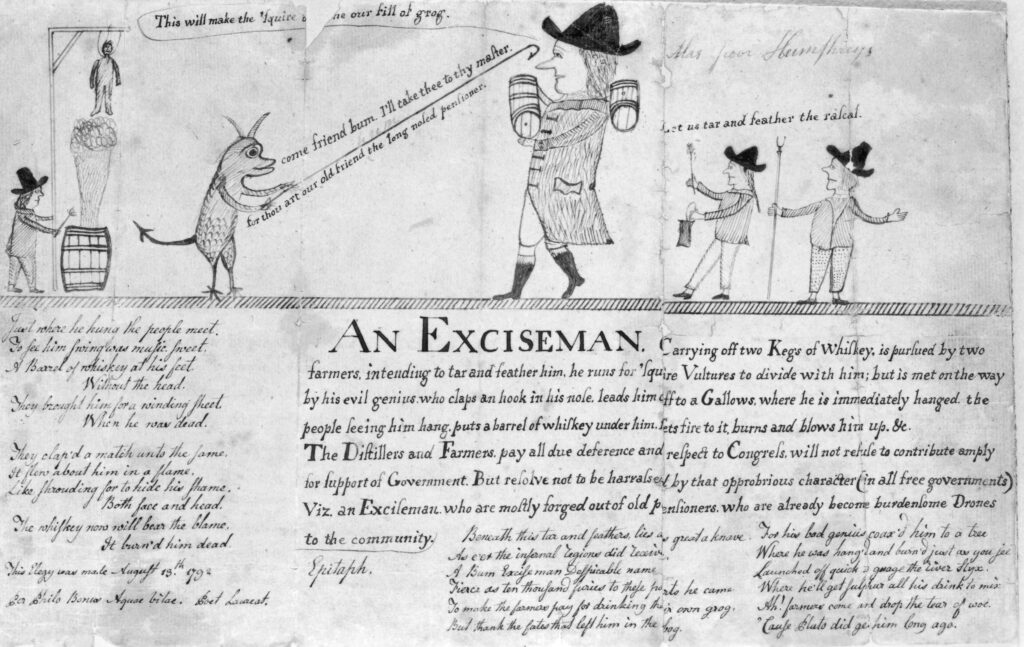

The conflict dragged on for several years, and when their initial efforts at peaceful non-compliance failed to secure the repeal of the excise, some western Pennsylvanians adopted tactics of violent resistance to the enforcement of the law. A number of excisemen (Document A) were accosted in the line of duty, tarred and feathered and (in at least one instance) tied up outside overnight in an attempt to coerce them into renouncing their commissions. When accounts of the violence reached the national government in Philadelphia, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (whose department was ultimately responsible for the revenues collected by the excise) prepared a report for President George Washington.

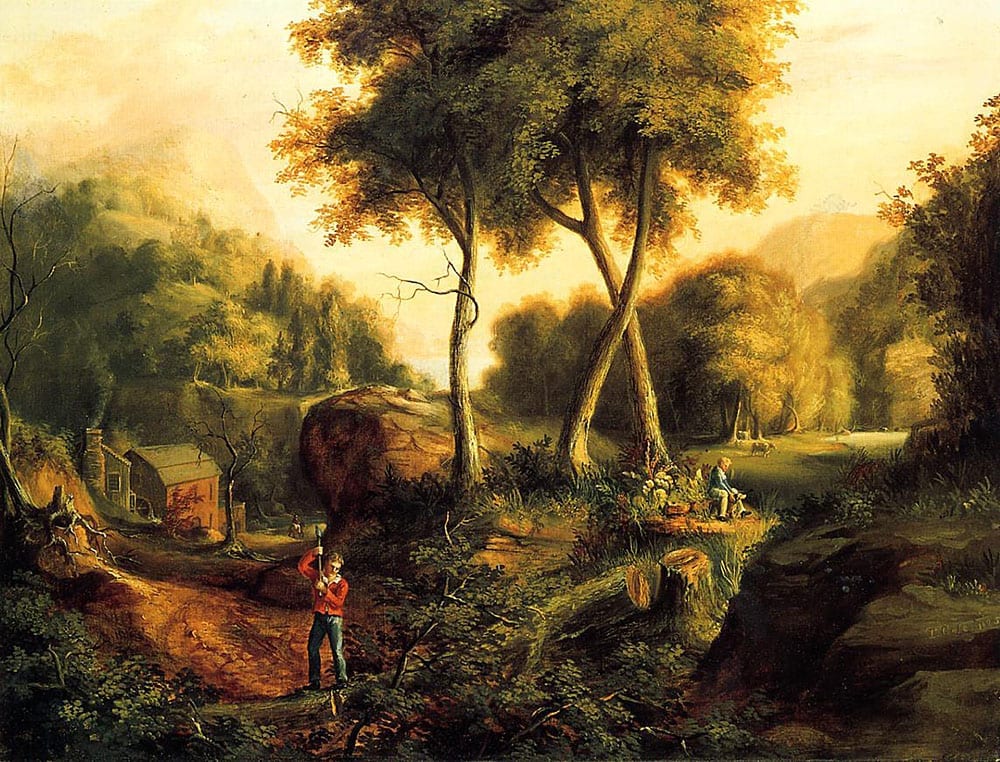

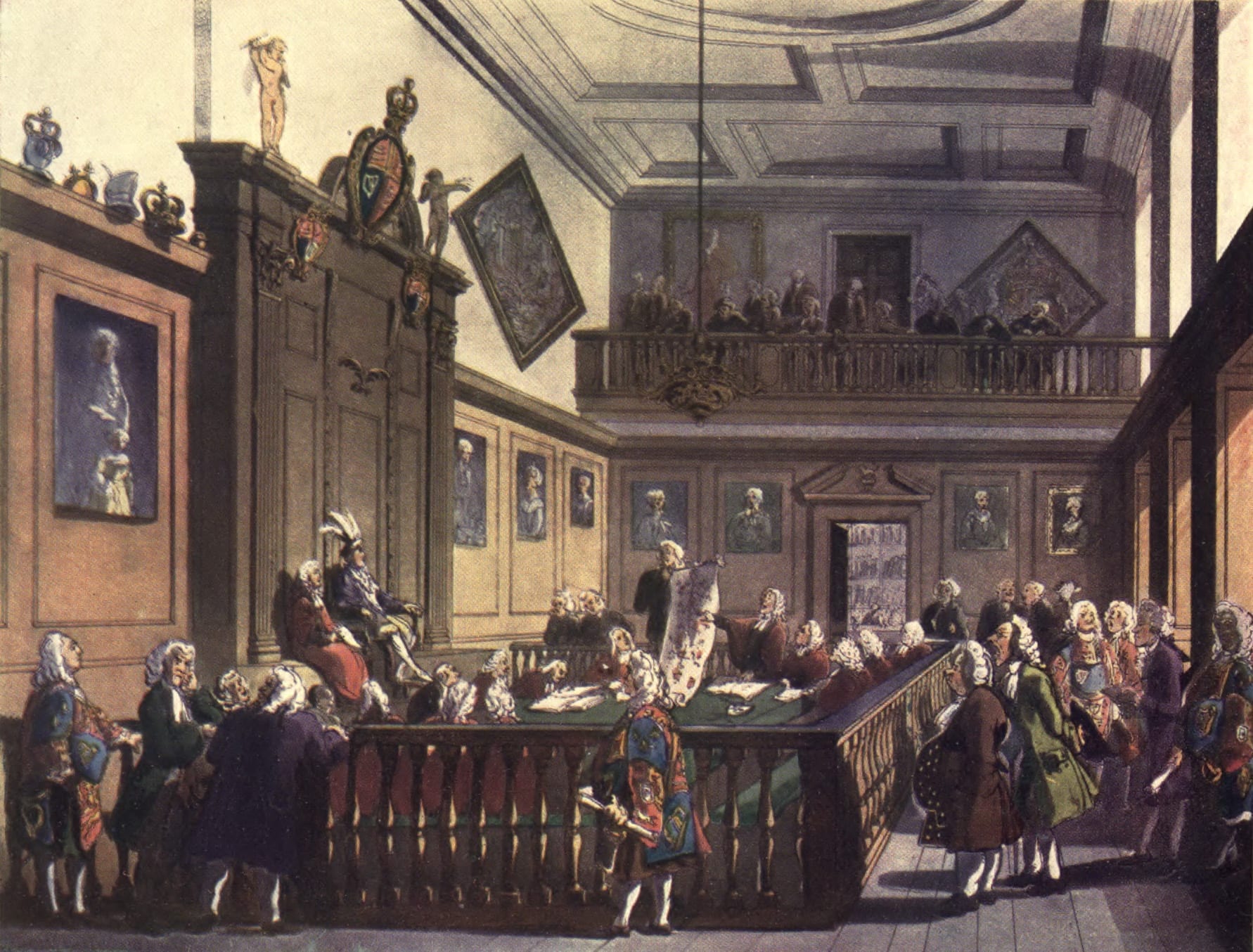

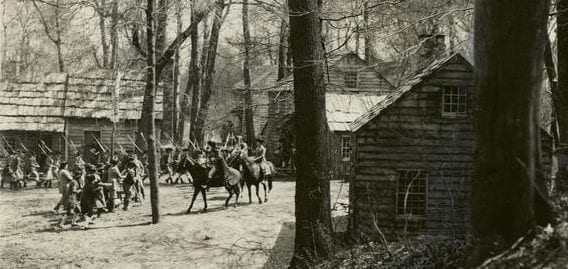

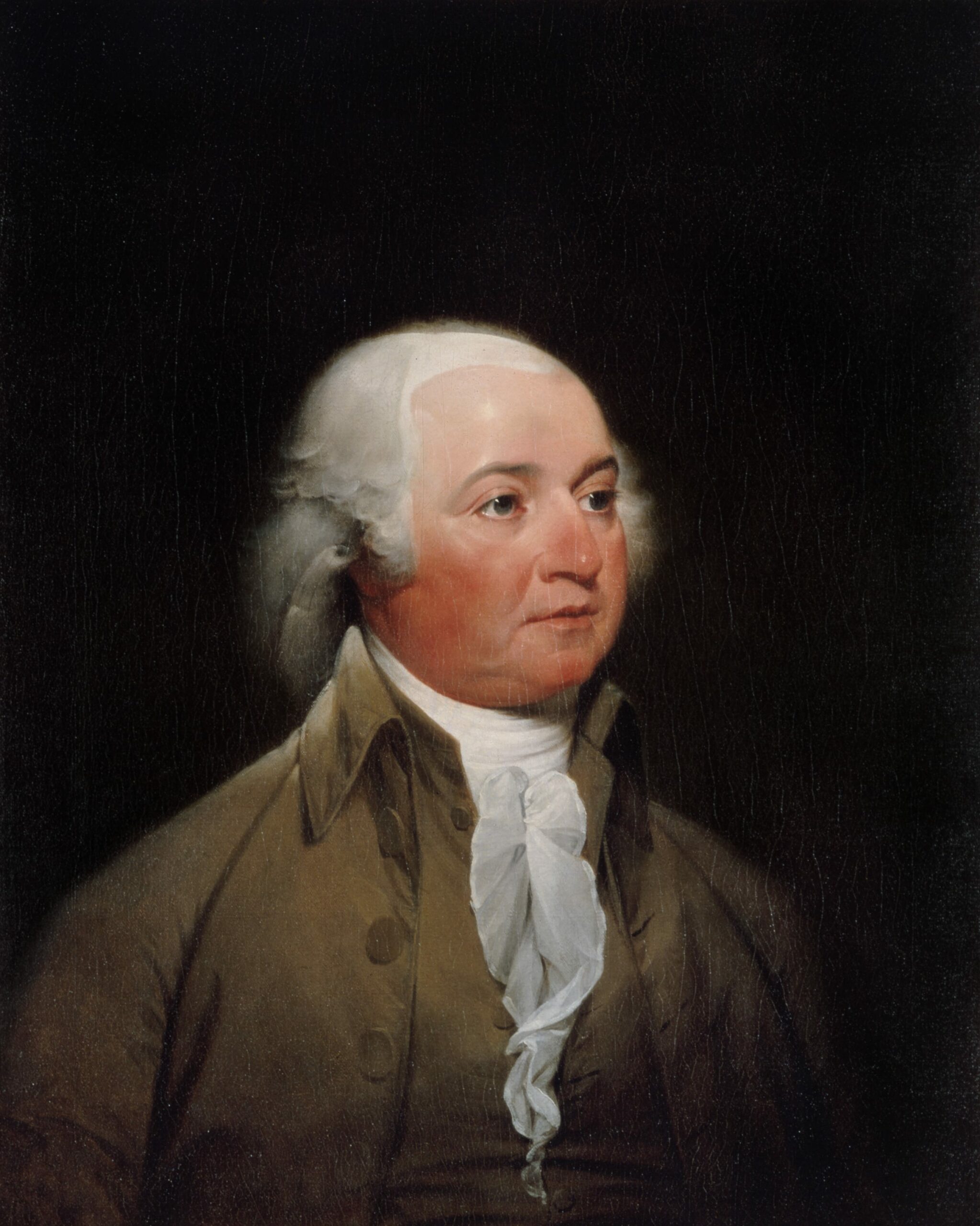

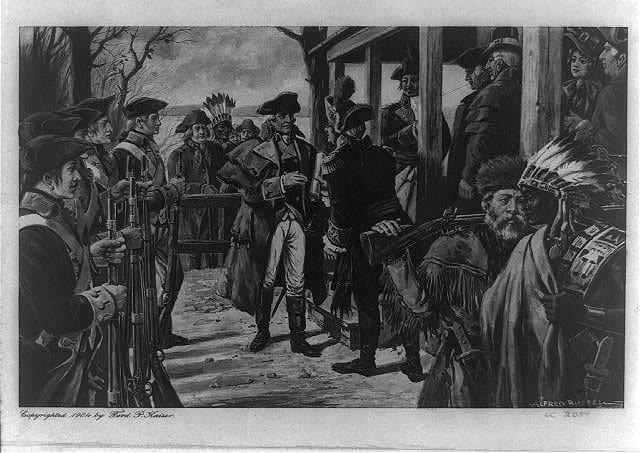

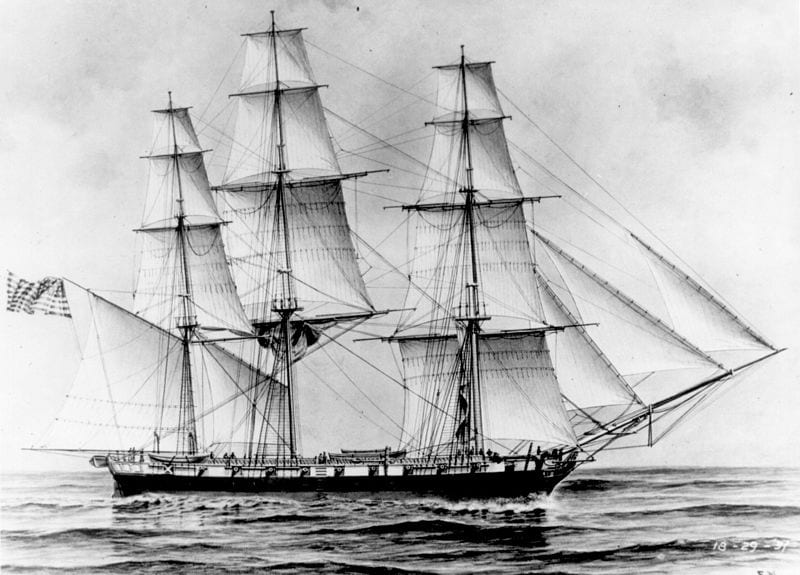

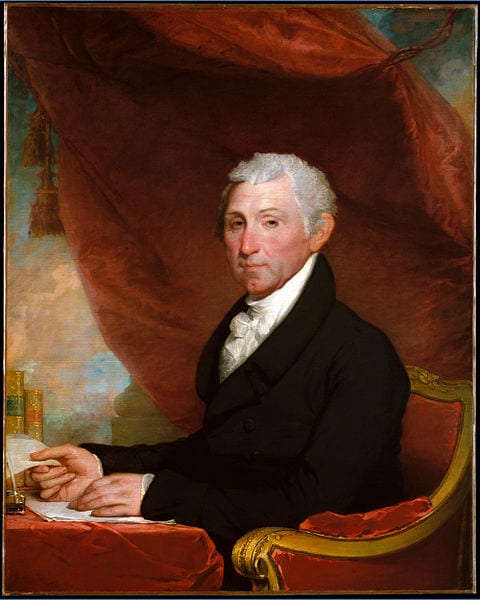

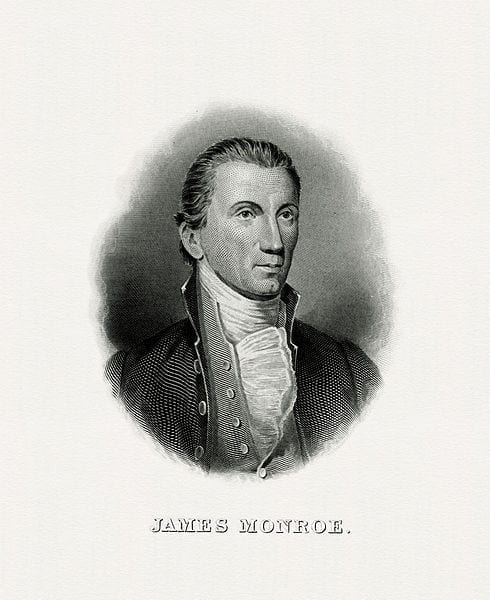

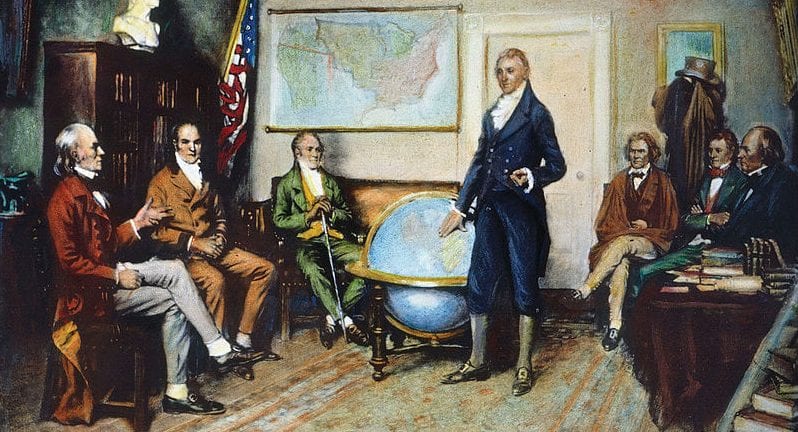

Hamilton’s report (Document B) begins by describing the situation as a “disagreeable crisis” but ends by labeling the parties involved as insurgents, and their resistance as a domestic insurrection. He is frequently credited with convincing the president that matters would not be resolved apart from the use of military force, with the result that Washington issued a presidential proclamation (Document C) to that effect. Meanwhile, Hamilton’s pseudonymous Tully essays (Document D) were meant to turn public opinion against the rebellion and bolster public support for the president’s decision to send in the militia. (In actuality, Washington himself took command of the nearly 13,000 troops that were marched to the West in October 1794, the only time an American president has actually served as a combat commander while in office; see Document F).

Hamilton’s essays and the marshaling of troops succeeded in quelling the rebellion without further violence. Yet the central question raised by the insurgency remained: to what extent and in what ways can citizens in a republic organize to resist laws they find unjust or immoral before becoming rebels or traitors? In the years following the incident, moderate opponents of the excise tax and other strongly national policies like it would offer opposing narratives of the insurrection in which they attempted to present the national government as oppressive.

William Findley (a Republican from Western Pennsylvania who served as a long-time member of the House of Representatives), for example, downplays the violence of the rebels and instead focuses on the government’s attempt to restrict the freedoms of speech and association of individual citizens (Document G). Such interpretations were repeated by many others over the course of John Adams’s presidency and doubtlessly helped to bolster the rise of the Jeffersonian Republicans as a substantial opposition party within national politics.

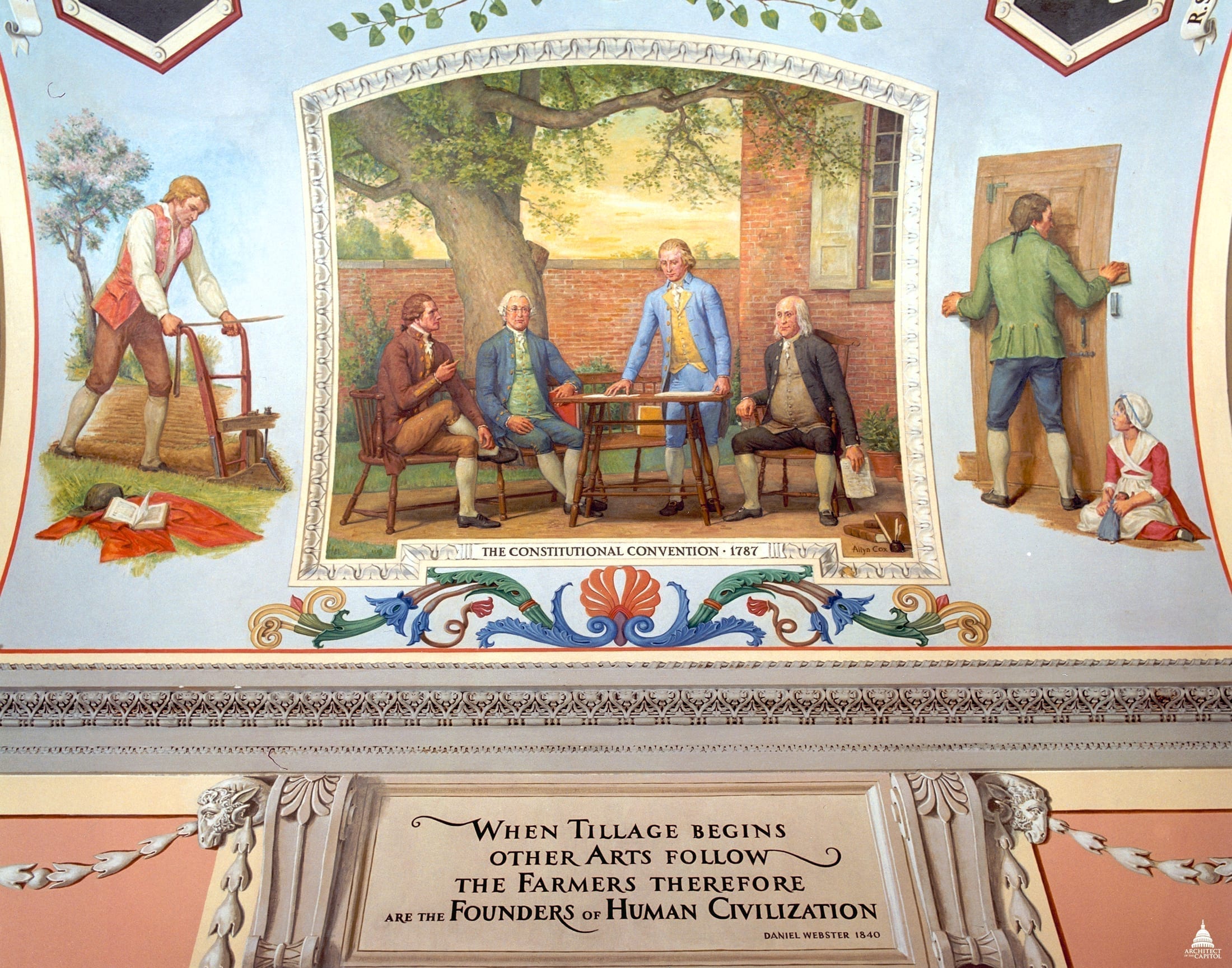

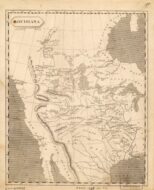

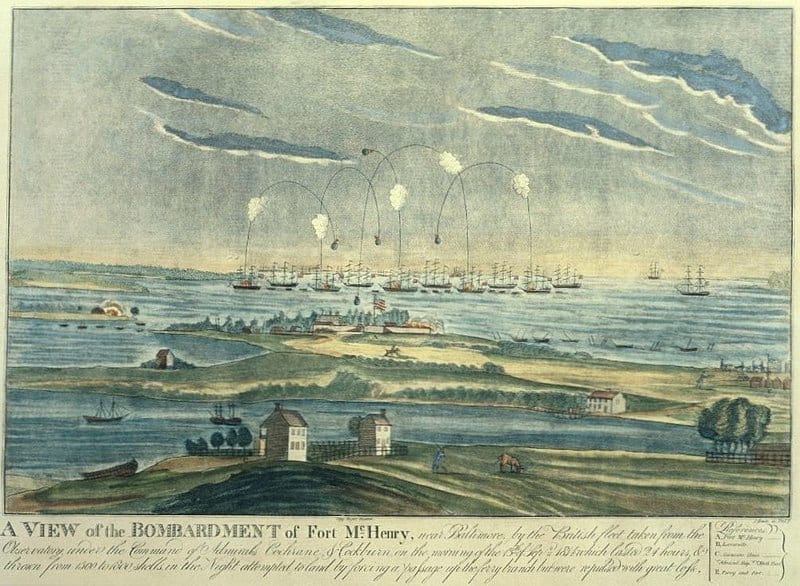

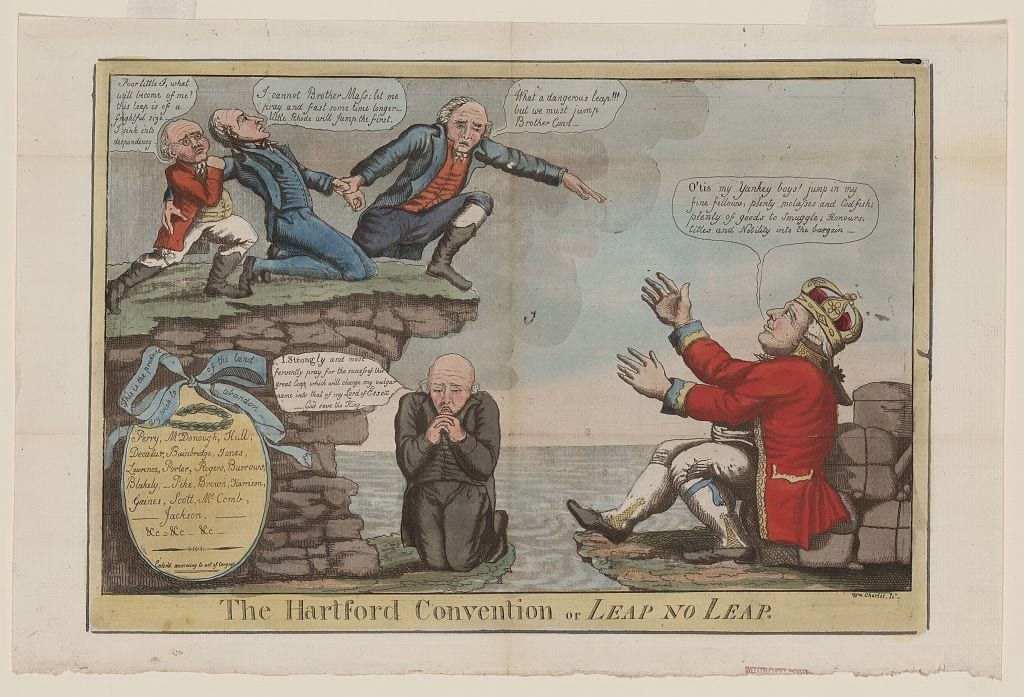

- Anonymous, An Exciseman, c. 1791

- Alexander Hamilton to George Washington, "The Disagreeable Crisis in the Western Counties," August 5, 1794

- George Washington, Whiskey Rebellion Proclamation, August 7, 1794

- (Alexander Hamilton), Tully Essays, August 23, 26, 28 and September 2, 1794

- William Findley, Defense of the Insurgents, 1796

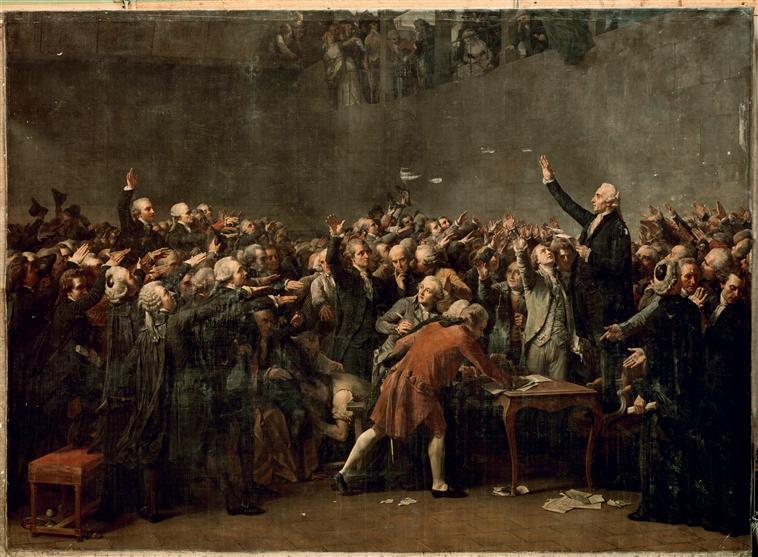

- Washington Reviewing the Western Army at Fort Cumberland, Maryland, oil on canvas, c. 1795, attributed to Frederick Kemmelmeyer

Anonymous, An Exciseman, c. 17911

An Exciseman, carrying off two kegs of Whiskey, is pursued by two farmers, intending to tar and feather him, he runs for Squire Vultures to divide with him; but is met on the way by his evil genius who claps an [sic] hook in his nose, leads him off to a Gallows, where he is immediately hanged. The people seeing him hang, puts [sic] a barrel of whiskey underneath him and blows him up. etc.

The Distillers and Farmers pay[ing] all due deference and respect to Congress will not refuse to contribute amply for support of government but resolve not to be harassed by the opprobrious character (in all free governments), Viz., an Exciseman, [a class of characters] who are mostly forged out of old pensioners, who are already become burdensome drones to the community.

Epitaph

Beneath this tar and feathers, lies as great a knave

As e’er the infernal legions did receive

A bum exciseman despicable name

Fierce as ten thousand furies to these ports he came

To make the farmers pay for drinking their own grog

But thank the fates that left him in the bog.

For his bad genius coaxed him to a tree

Where he was hanged and burned, just as you see.

Launched off quick to gauge the River Styx2

Where he’ll get Sulphur all his drink to mix.

Ah! Farmers come and drop the tear of woe

‘Cause Pluto3 did get him long ago.

Just where he hung the people meet,

To see him swing was music sweet

A barrel of whiskey at his feet

Without the head.

They brought him for a winding sheet4,

When he was dead.

They clap’d a match unto the same

It flew about him in a flame,

Like shrouding5 for to hide his shame

Both face and head.

The whiskey now will bear the blame;

It burn’d him dead.

This elegy was made August 13, 1792 per Philo bonus Aqua Vitae, Poet Laureate

Back to TopAlexander Hamilton to George Washington, “The Disagreeable Crisis in the Western Counties,” August 5, 17946

Sir,

The disagreeable crisis at which matters have lately arrived in some of the western counties of Pennsylvania, with regard to the laws laying duties on spirits distilled within the United States and on stills, seems to render proper a review of the circumstances which have attended those laws in that scene, from their commencement to the present time—and of the conduct which has hitherto been observed on the part of the government, its motives and effect; in order to a better judgement of the measures necessary to be pursued in the existing emergency.

The opposition to those laws in the four most western counties of Pennsylvania (Alleghany, Washington, Fayette and Westmoreland) commenced as early as they were known to have been passed. It has continued, with different degrees of violence, in the different counties, and at different periods. . . .

The opposition first manifested itself in the milder shape of the circulation of opinions unfavorable to the law—and calculated by the influence of public disesteem to discourage the accepting or holding of offices under it, or the complying with it by those who might be so disposed; to which was added the show of a discontinuance of the business of distilling.

These expedients were shortly after succeeded by private associations to forbear compliances with the law. But it was not long before these more negative modes of opposition were perceived to be likely to prove ineffectual. And in proportion as this was the case, and as the means of introducing the laws into operation were put into execution, the disposition to resistance became more turbulent and more inclined to adopt and practice violent expedients. The officers now began to experience marks of contempt and insult. Threats against them became frequent and loud; and after some time, these threats were ripened into acts of ill treatment and outrage.

These acts of violence were preceded by certain meetings of malcontent persons, who entered into resolutions calculated at once to confirm, inflame and systematize the spirit of opposition.

The first of these meetings was holden at a place called Red Stone Old Fort on the 27th of July 1791, where it was concerted, that county committees should be convened in the four counties at the respective seats of justice therein. On the 23d of August following, one of these committees assembled in the County of Washington. . . .

This meeting passed some intemperate resolutions, which were afterwards printed in the Pittsburgh Gazette, containing a strong censure on the law, declaring that any person who had accepted or might accept an office under congress in order to carry it into effect, should be considered as inimical to the interests of the country; and recommending to the citizens of Washington County to treat every person who had accepted or might thereafter accept any such office with contempt, and absolutely to refuse all kind of communication or intercourse with the officers, and to withhold from them all aid, support or comfort.

Not content with this vindictive proscription of those, who might esteem it their duty, in the capacity of officers, to aid in the execution of the constitutional laws of the land—The meeting proceeded to pass another resolution on a matter essentially foreign to the object which had brought them together, namely the salaries and compensations allowed by Congress to the officers of government generally, which they represent as enormous, manifesting by their zeal to accumulate topics of censure, that they were actuated, not merely by the dislike of a particular law, but by a disposition to render the government itself unpopular and odious.

This meeting, in further prosecution of their plan, deputed three of their members to meet delegates from the counties of Westmoreland, Fayette, and Alleghany on the first Tuesday of September following for the purpose of expressing the sense of the people of those Counties, in an address to the Legislature of the United States, upon the subject of the Excise Law and other grievancies. . . .

This meeting entered into resolutions more comprehensive in their objects & not less inflammatory in their tendency, than those which had before passed the meeting in Washington. Their resolutions contained severe censures not only on the law which was the immediate subject of objection; but upon what they termed the exorbitant salaries of Officers; the unreasonable interest of the public debt, the want of discrimination between original holders and transferees, and the institution of a National Bank. . . .

A representation to Congress and a remonstrance to the Legislature of Pennsylvania against the Law more particularly complained of were prepared by this meeting—published together with their other proceedings in the Pittsburgh Gazette & afterwards presented to the respective bodies to whom they were addressed.

These meetings composed of very influential individuals and conducted without moderation or prudence are justly chargeable with the excesses, which have been from time to time committed; serving to give consistency to an opposition which has at length matured to a point, that threatens the foundations of the government and of the Union, unless speedily & effectually subdued.

On the 6th of the same month of September, the opposition broke out in an act of violence upon the person and property of Robert Johnson Collector of the Revenue for the Counties of Alleghany and Washington.

A party of men armed and disguised way-laid him at a place on Pidgeon Creek in Washington County, seized, tarred and feathered him, cut off his hair, and deprived him of his horse, obliging him to travel on foot a considerable distance in that mortifying and painful situation. . . .

It seemed highly probable … that the ordinary course of civil process would be ineffectual for enforcing the execution of the law in the scene in question—and that a perseverance in this course might lead to a serious concussion. The law itself was still in the infancy of its operation and far from established in other important portions of the Union. Prejudices against it had been industriously disseminated—misrepresentations diffused, misconceptions fostered. The Legislature of the United States had not yet organized the means, by which the Executive could come in aid of the Judiciary, when found incompetent to the execution of the laws. If neither of these impediments to a decisive exertion had existed, it was desirable, especially in a republican government, to avoid what is in such cases the ultimate resort, ‘till all the milder means had been tried without success.

Under the United influence of these considerations, it appeared advisable to forbear urging coercive measures, till the laws had gone into more extensive operation, till further time for reflection and experience of its operation had served to correct false impressions and inspire greater moderation and till the Legislature had had an opportunity by a revision of the law to remove as far as possible objections and to reinforce the provisions for securing its execution.

. . .

Not long after a person of the name of Roseberry underwent the humiliating punishment of tarring and feathering with some aggravations; for having in conversation hazarded the very natural and just, but unpalatable remark, that the inhabitants of that country could not reasonably expect protection from a Government, whose laws they so strenuously opposed. . . .

In the session of Congress, which commenced in October 1791, the law laying a duty on distilled spirits and stills came under the revision of Congress as had been anticipated. By an Act passed May 8th 1792, during that session, material alterations were made in it—Among these the duty was reduced to a rate so moderate, as to have silenced complaint on that head—and a new and very favorable alternative was given to the distiller, that of paying a monthly, instead [of] a yearly rate, according to the capacity of his still, with liberty to take a license for the precise term, which he should intend to work it, & to renew that license for a further term or terms.

At the same time, another engine of opposition was in operation—Agreeable to a previous notification, there met at Pittsburgh on the 21st of August a number of persons styling themselves “A meeting of sundry Inhabitants of the Western Counties of Pennsylvania” who appointed John Canon Chairman and Albert Gallatin Clerk.

This Meeting entered into resolutions not less exceptionable than those of its predecessors—The preamble suggests that a tax on spirituous liquors is unjust in itself and oppressive upon the poor, that internal taxes upon consumption must in the end destroy the liberties of every Country in which they are introduced—that the law in question, from certain local circumstances which are specified, would bring immediate distress and ruin upon the Western Country, and concludes with the sentiment, that they think it their duty to persist in remonstrances to Congress, and in every other legal measure, that may obstruct the operation of the law.

The resolutions then proceed, first, to appoint a committee to prepare and cause to be presented to Congress an address stating objections to the Law, and praying for its repeal—Secondly to appoint committees of correspondence for Washington, Fayette and Alleghany, charged to correspond together and with such committee as should be appointed for the same purpose in the County of Westmoreland, or with any committees of a similar nature, that might be appointed in other parts of the United States; and also if found necessary to call together either general meetings of the people, in their respective counties, or conferences of the several committees; And lastly to declare, that they will in future consider those who hold offices for the collection of the duty as unworthy of their friendship, that they will have no intercourse nor dealings with them, will withdraw from them every assistance, withhold all the comforts of life which depend upon those duties, that as men and fellow citizens we owe to each other, and will upon all occasions treat them with contempt; earnestly recommending it to the people at large to follow the same line of Conduct towards them.

The idea of pursuing legal measures to obstruct the operation of a law needs little comment: legal measures may be pursued to procure the repeal of a law, but to obstruct its operation presents a contradiction in terms. The operation or what is the same thing, the execution of a law cannot be obstructed, after it has been constitutionally enacted, without illegality and crime. The expression quoted is one of those phrases which can only be used to conceal a disorderly & culpable intention under forms that may escape the hold of the law.

Neither was it difficult to perceive, that the Anathema pronounced against the officers of the revenue placed them in a state of virtual outlawry, and operated as a signal to all those who were bold enough to encounter the guilt and the danger to violate both their lives and their properties.

. . . In June following the Inspector of the Revenue was burnt in Effigy in Alleghany County at a place and on a day of some public election, with much display, in the presence of and without interruption from Magistrates and other public Officers.

. . . About twelve persons armed & painted black, in the night of the 6th of June, broke into the house of John Lynn, where the office was kept, and after having treacherously seduced him to come downstairs and put himself in their power by a promise of safety to himself and his house—they seized and tied him, threatened to hang him—took him to a retired spot in the neighboring wood and there after cutting off his hair, tarring and feathering him, swore him never again to allow the use of his house for an office, never to disclose their names, and never again to have any sort of agency in aid of the excise—having done which, they bound him naked to a tree and left him in that situation, till morning, when he succeeded in extricating himself. Not content with this, the malcontents some days after made him another visit, pulled down part of his house—and put him in a situation to be obliged to become an exile from his own home and to find an asylum elsewhere.

The increasing energy of the opposition rendered it indispensable to meet the evil with proportional decision—The idea of giving time for the law to extend itself in Scenes where the dissatisfaction with it was the effect not of an improper spirit, but of causes which were of a nature to yield to reason, reflection, and experience (which had constantly weighed in the estimate of the measures proper to be pursued) had had its effect, in an extensive degree. The experiment too had been long enough tried to ascertain, that where resistance continued, the root of the evil lay deep; and required measures of greater efficacy than had been pursued. The laws had undergone repeated revisions of the Legislative representatives of the Union, and had virtually received their repeated sanction with none or very feeble attempts to effect their repeal; affording an evidence of the general sense of the community in their favor. Complaint began to be loud from complying quarters, against the impropriety and injustice of suffering the laws to remain unexecuted in others.

Under the united influence of these considerations, there was no choice but to try the efficiency of the laws in prosecuting with vigor delinquents and offenders. . . .

Back to TopGeorge Washington, Whiskey Rebellion Proclamation, August 7, 17947

Whereas, combinations to defeat the execution of the laws laying duties upon spirits distilled within the United States and upon stills have from the time of the commencement of those laws existed in some of the western parts of Pennsylvania.

And whereas, the said combinations, proceeding in a manner subversive equally of the just authority of government and of the rights of individuals, have hitherto effected their dangerous and criminal purpose by the influence of certain irregular meetings whose proceedings have tended to encourage and uphold the spirit of opposition by misrepresentations of the laws calculated to render them odious; by endeavors to deter those who might be so disposed from accepting offices under them through fear of public resentment and of injury to person and property, and to compel those who had accepted such offices by actual violence to surrender or forbear the execution of them; by circulation of vindictive menaces against all those who should otherwise, directly or indirectly, aid in the execution of the said laws, or who, yielding to the dictates of conscience and to a sense of obligation, should themselves comply therewith; by actually injuring and destroying the property of persons who were understood to have so complied; by inflicting cruel and humiliating punishments upon private citizens for no other cause than that of appearing to be the friends of the laws; by intercepting the public officers on the highways, abusing, assaulting, and otherwise ill-treating them; by going into their houses in the night, gaining admittance by force, taking away their papers, and committing other outrages, employing for these unwarrantable purposes the agency of armed banditti disguised in such manner as for the most part to escape discovery;

And whereas . . . the endeavors of the executive officers to conciliate a compliance with the laws by explanations, by forbearance, and even by particular accommodations founded on the suggestion of local considerations, have been disappointed of their effect by the machinations of persons whose industry to excite resistance has increased with every appearance of a disposition among the people to relax in their opposition and to acquiesce in the laws, insomuch that many persons in the said western parts of Pennsylvania have at length been hardy enough to perpetrate acts, which I am advised amount to treason, being overt acts of levying war against the United States. . . .

And whereas, it is in my judgment necessary under the circumstances of the case to take measures for calling forth the militia in order to suppress the combinations aforesaid, and to cause the laws to be duly executed; and I have accordingly determined so to do, feeling the deepest regret for the occasion, but withal the most solemn conviction that the essential interests of the Union demand it, that the very existence of government and the fundamental principles of social order are materially involved in the issue, and that the patriotism and firmness of all good citizens are seriously called upon, as occasions may require, to aid in the effectual suppression of so fatal a spirit;

Therefore, and in pursuance of the proviso above recited, I, George Washington, President of the United States, do hereby command all persons, being insurgents, as aforesaid, and all others whom it may concern, on or before the 1st day of September next to disperse and retire peaceably to their respective abodes. And I do moreover warn all persons whomsoever against aiding, abetting, or comforting the perpetrators of the aforesaid treasonable acts; and do require all officers and other citizens, according to their respective duties and the laws of the land, to exert their utmost endeavors to prevent and suppress such dangerous proceedings. . . .

G. WASHINGTON

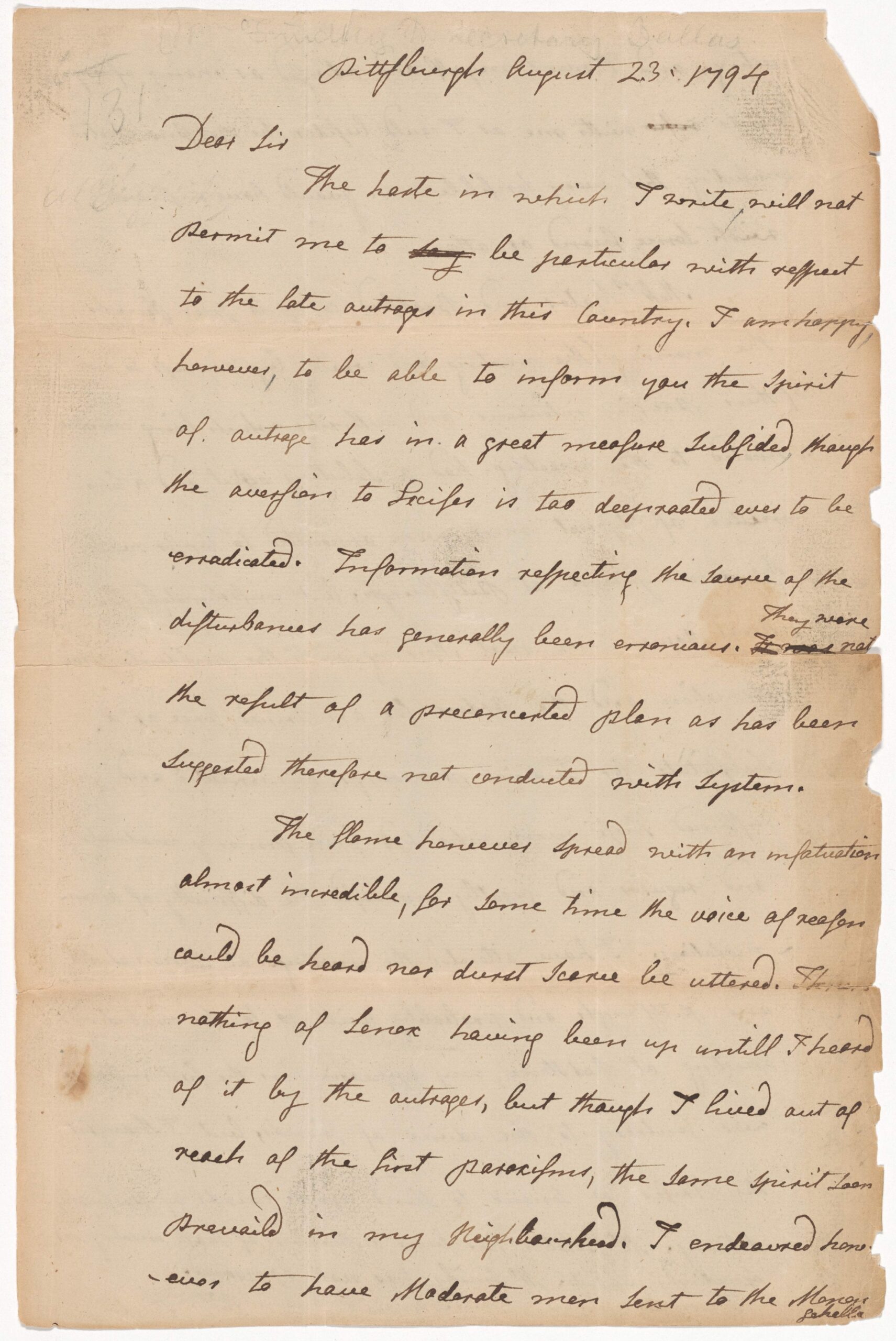

Back to Top(Alexander Hamilton), Tully Essays, August 23, 26, 28 and September 2, 17948

LETTER I | August 23, 1794

It has from the first establishment of your present constitution been predicted, that every occasion of serious embarrassment which should occur in the affairs of the government—every misfortune which it should experience, whether produced from its own faults or mistakes, or from other causes, would be the signal of an attempt to overthrow it, or to lay the foundation of its overthrow, by defeating the exercise of constitutional and necessary authorities. The disturbances which have recently broken out in the western counties of Pennsylvania furnish an occasion of this sort. It remains to see whether the prediction which has been quoted, proceeded from an unfounded jealousy excited by partial differences of opinion, or was a just inference from causes inherent in the structure of our political institutions. . . .

LETTER II | August 26, 1794

. . . The Constitution you have ordained for yourselves and your posterity contains this express clause, “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and Excises, to pay the debts, and provide for the common defence and general welfare of the United States.” You have then, by a solemn and deliberate act, the most important and sacred that a nation can perform, pronounced and decreed, that your Representatives in Congress shall have power to lay Excises. You have done nothing since to reverse or impair that decree.

. . . But the four western counties of Pennsylvania, undertake to rejudge and reverse your decrees[. Y]ou have said, “The Congress shall have power to lay Excises.” They say, “The Congress shall not have this power.” Or what is equivalent—they shall not exercise it:—for a power that may not be exercised is a nullity. Your Representatives have said, and four times repeated it, “an excise on distilled spirits shall be collected.” They say it shall not be collected. We will punish, expel, and banish the officers who shall attempt the collection. We will do the same by every other person who shall dare to comply with your decree expressed in the Constitutional character; and with that of your Representative expressed in the Laws. The sovereignty shall not reside with you, but with us. If you presume to dispute the point by force—we are ready to measure swords with you. . . .

If there is a man among us who shall . . . inculcate directly, or indirectly, that force ought not to be employed to compel the Insurgents to a submission to the laws, if the pending experiment to bring them to reason (an experiment which will immortalize the moderation of the government) shall fail; such a man is not a good Citizen; such a man however he may prate and babble republicanism, is not a republican; he attempts to set up the will of a part against the will of the whole, the will of a faction, against the will of nation, the pleasure of a few against your pleasure; the violence of a lawless combination against the sacred authority of laws pronounced under your indisputable commission.

Mark such a man, if such there be. The occasion may enable you to discriminate the true from pretended Republicans; your friends from the friends of faction. ‘Tis in vain that the latter shall attempt to conceal their pernicious principles under a crowd of odious invectives against the laws. Your answer is this: “We have already in the Constitutional act decided the point against you, and against those for whom you apologize. We have pronounced that excises may be laid and consequently that they are not as you say inconsistent with Liberty. Let our will be first obeyed and then we shall be ready to consider the reason which can be afforded to prove our judgement has been erroneous. . . . We have not neglected the means of amending in a regular course the Constitutional act. . . . In a full respect for the laws we discern the reality of our power and the means of providing for our welfare as occasion may require; in the contempt of the laws we see the annihilation of our power; the possibility, and the danger of its being usurped by others & of the despotism of individuals succeeding to the regular authority of the nation.”

That a fate like this may never await you, let it be deeply imprinted in your minds and handed down to your latest posterity, that there is no road to despotism more sure or more to be dreaded than that which begins at anarchy.

LETTER III | August 28, 1794

If it were to be asked, What is the most sacred duty and the greatest source of security in a Republic? the answer would be, An inviolable respect for the Constitution and Laws—the first growing out of the last. It is by this, in a great degree, that the rich and powerful are to be restrained from enterprises against the common liberty—operated upon by the influence of a general sentiment, by their interest in the principle, and by the obstacles which the habit it produces erects against innovation and encroachment. It is by this, in a still greater degree, that caballers, intriguers, and demagogues are prevented from climbing on the shoulders of faction to the tempting seats of usurpation and tyranny.

. . . Government is frequently and aptly classed under two descriptions, a government of force and a government of laws; the first is the definition of despotism—the last, of liberty. But how can a government of laws exist where the laws are disrespected and disobeyed? Government supposes controul. It is the power by which individuals in society are kept from doing injury to each other and are bro’t to co-operate to a common end. The instruments by which it must act are either the authority of the Laws or force. If the first be destroyed, the last must be substituted; and where this becomes the ordinary instrument of government there is an end to liberty.

Those, therefore, who preach doctrines, or set examples, which undermine or subvert the authority of the laws, lead us from freedom to slavery; they incapacitate us for a government of laws, and consequently prepare the way for one of force, for mankind must have government of one sort or another.

There are indeed great and urgent cases where the bounds of the constitution are manifestly transgressed, or its constitutional authorities so exercised as to produce unequivocal oppression on the community, and to render resistance justifiable. But such cases can give no color to the resistance by a comparatively inconsiderable part of a community, of constitutional laws distinguished by no extraordinary features of rigor or oppression, and acquiesced in by the body of the community.

Such a resistance is treason against society, against liberty, against everything that ought to be dear to a free, enlightened, and prudent people. To tolerate were to abandon your most precious interests. Not to subdue it, were to tolerate it. . . .

LETTER IV | September 2, 1794

. . . Fellow Citizens—You are told, that it will be intemperate to urge the execution of the laws which are resisted—what? will it be indeed intemperate in your Chief Magistrate, sworn to maintain the Constitution, charged faithfully to execute the Laws, and authorized to employ for that purpose force when the ordinary means fail—will it be intemperate in him to exert that force, when the constitution and the laws are opposed by force? Can he answer it to his conscience, to you not to exert it?

Yes, it is said; because the execution of it will produce civil war, the consummation of human evil.

Fellow-Citizens—Civil War is undoubtedly a great evil. It is one that every good man would wish to avoid, and will deplore if inevitable. But it is incomparably a less evil than the destruction of Government. The first brings with it serious but temporary and partial ills—the last undermines the foundations of our security and happiness—where should we be if it were once to grow into a maxim, that force is not to be used against the seditious combinations of parts of the community to resist the laws? . . . The Hydra Anarchy would rear its head in every quarter. The goodly fabric you have established would be rent assunder, and precipitated into the dust. . . . You know that the power of the majority and liberty are inseparable—destroy that, and this perishes. . . .

Tully.

Back to TopWilliam Findley, Defense of the Insurgents, 17969

. . . It is true, it may be pled that popular meetings are often conducted with indiscretion, and have a tendency to promote licentiousness. This is admitted; but it does not therefore follow that such meetings should be prohibited by law or denounced by government. Doing so, would be reducing the people to mere machines, and subverting the very existence of liberty. It is the duty of the legislature not only to accommodate the laws to the people’s interests, but even, as far as possible, to their preconceptions; for as a republican government rests on the people’s confidence, whatever weakens that confidence saps the foundations of the government as effectually as treason and rebellion, though not so rapidly. There are few instances of treason and rebellion which may not be traced to indiscreet laws as their source. It is generally one indiscretion exciting another.

It will not do to say, that to hold meetings to remonstrate against the passing of a law is admissible, but that to remonstrate against an existing law is improper. Such doctrine in this extensive country is absurd, for it must always happen, that a great proportion of the people, who are to be governed by the laws, know nothing about them ‘til they are enacted or in operation, consequently cannot petition against their passage.

It is equally absurd to assert, that because our laws are enacted by our own representatives, therefore we ought to submit to them without remonstrance, ‘til our representatives, who know our circumstances, and partake of our interests, think proper to repeal them. This doctrine is supported by a presumption, that a government of representatives can never mistake the true interests of their constituents, not be corrupted or fall into partial combinations, whereas the contrary is presumable from the nature of man, and verified by immemorial experience.

If the people have a right to petition for the repeal of a law, or remonstrate against its injustice or inexpediency, surely, they have a right to meet, publish their sentiments, and correspond through the whole extent of the country affected by the laws, without the imputation of combining against the government. Their characters indeed are responsible to public opinion for the indiscrete use of that right, and their persons and property to the laws for the infractions committed on them.

Experience will not justify the claim of implicit obedience to the laws even of a representative legislature. Even in such there may be combinations so strong as to subvert the Constitution itself; and as the disposal of the public property and the administration of the national force is necessarily vested in the government, temptations, too strong for the ordinary portion of virtue enjoyed by mankind, may present themselves too successfully to the avarice or ambition of those vested with the power of dispensing the public will. Instances of this are to be found in the history of all nations, and proofs of it are not wanting even among ourselves, though as a nation we are yet in our infancy.

We are certainly under a moral obligation to preserve our own life and the life of our neighbours. Every instance of actual opposition to government, obliges it to have recourse to force and coercion for its own preservation, for the authority of government cannot be distinguished from the government itself. Though forcible opposition has often been made to particular laws, without the remotest intention in those who opposed the law to overturn the government, yet it is not to be supposed, that those who administer the government will be moved to change their measures by a defiance of their power to support them. Nor indeed can this be done in a republican government, without such an imputation of weakness as will invite to forcible opposition from every discontented party. Therefore citizens who conceive themselves oppressed by partial laws, should consider that a defiance of the power of government, by forcible opposition to the authority of the laws, eventually leads to hostility and bloodshed, and that there is no telling the end of those measures from their beginning. Everything that has a tendency to agitate the public mind to an unusual degree, ought to be avoided, because when the mind is highly agitated with respect to public measures it is too much disturbed to judge deliberately and is predisposed to act without discretion. The public mind may be agitated by those who cannot direct or control its exertions. We are under a moral obligation to respect government, not only as a divine ordinance, but also as a moral compact, binding the people to one another for its support.

It is certain, however, that the government and law of some countries are not worth preserving, and even where a government is good in itself it may be perverted in the administration. As it is for the promoting of mutual happiness and security only that government is valuable, therefore the power of altering or amending governments is expressly declared to be in the people, who are the judges of their own happiness, by some constitutions. It is, however, radically in them, whether expressed in a written instrument or not.

When the change of a government, a revolt from it, or a temporary opposition to its laws, such as the opposition of the colonies to the stamp and tea acts was, is believed to be morally right, it is yet a matter of the greatest delicacy, to calculate with accuracy with respect to the prudence or policy of commencing the opposition contemplated. When the mind is highly agitated, it is very unfit to examine the resources to support opposition, or to calculate with precision the probable consequences of it. . . .

. . . A democratic society had been erected at Washington town, a few months preceding the insurrection, and it published some intemperate resolutions respecting the conduct of government relative to the navigation of the Mississippi, the appointment of a chief justice and a senator as ambassadors to Europe, etc. But I do not remember that they said anything against the excise law. Their resolutions were written in imitation of resolutions that had been published in Kentucky. Though there is no proof that these publications had any influence in promoting the insurrections, yet the damned democratic societies, as they were called, were considered as the cause of it by many in the army, from the generals down to the privates. I found too, that it was generally thought that the country was full of those societies, though in fact, there was but one, and that one had been of short duration and composed of but few members. . . .

The journals of Congress and the debates published in the newspapers in the winter following will give a standing testimony of the irritation that prevailed at that time against democratic societies, not only in the army, but in the councils of the United States. The attempt in government to suppress popular societies had a tendency to revive them when they were on the decline. I have ever thought it impolitic in government to denounce where it cannot punish. Societies cannot be suppressed in a free government, nor should it be attempted. They will do good or ill according to the sense and discretion of those who compose them: therefore, in order to reform societies we must begin with making men wiser and better; when they blazon the measures of administration or panegyrize the persons who conducted them, they are not denounced, therefore, when they do otherwise they must be tolerated.

. . . In June 1791, the operation of the excise was to commence . . . an advertisement was published, inviting the citizens of the western counties to meet at Redstone Old Fort, to consider and give advice how they should proceed with respect to the excise law . . . I never yet knew who first promoted the meeting, but the design was lawful and proper, it was to conduct measures for petitioning Congress in order to quiet the minds of the people.

. . . The great error among the people was an opinion that an immoral law might be opposed and yet the government respected, and all the other laws obeyed, and they firmly believed that the excise law was an immoral one. . . .

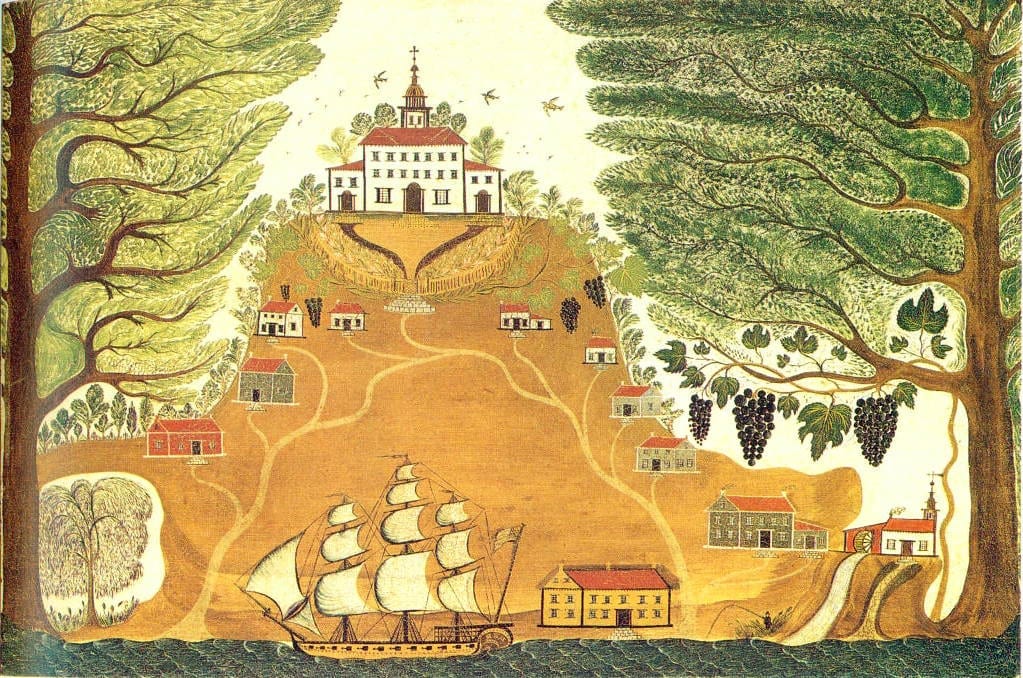

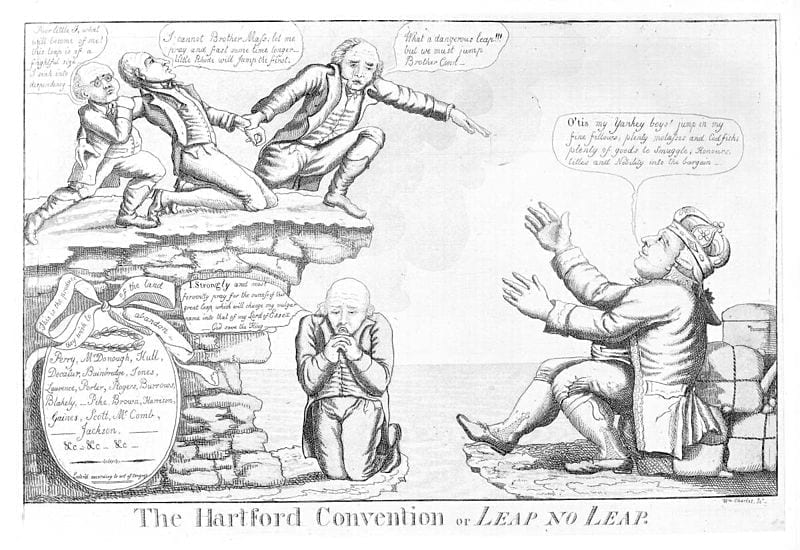

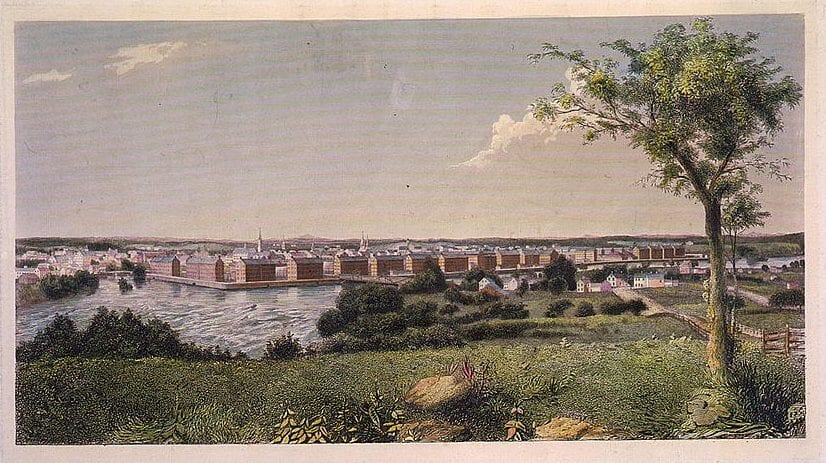

Washington Reviewing the Western Army at Fort Cumberland, Maryland, Attributed to Frederick Kemmelmeyer, c. 1795

- 1. Photo by Fotosearch/Getty Images, from an original in the National Archives

- 2. In Greek mythology, the River Styx was the boundary between the land of the living and the realm of the dead.

- 3. The god of the underworld; this name was more commonly used in Roman than in Greek mythology.

- 4. A winding sheet is simply a large length of cloth used to wrap a body prior to burial.

- 5. The poet here plays on the double meaning of "shrouding" - it can refer either to the sheet used to wind around the dead body, in essence hiding it from the eyes of the mourners, or to the act of hiding something from sight more generally.

- 6. Founders Online, National Archives

- 7. Claypoole's Daily Advertiser, August 11, 1794.

- 8. Dunlap and Claypoole's American Daily Advertiser.

- 9. William Findley, History of the Insurrection in the Four Western Counties of Pennsylvania: in the Year M.DCC.XCIV. With a Recital of the Circumstances Specifically Connected Therewith: and an Historical Review of the Previous Situation of the Country (Philadelphia: Samuel Harrison Smith, 1796), pp. 47-50, 53-55; 130-131, 166-167.

- 10. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1963.

House Debate on the Establishment of Post Roads

December 31, 1791

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.