Theodore Roosevelt Launches the Great White Fleet

The Great White Fleet was the result of Theodore Roosevelt’s determination to build a modern navy and flex American military muscle. Its global voyage was a showcase of American naval power.

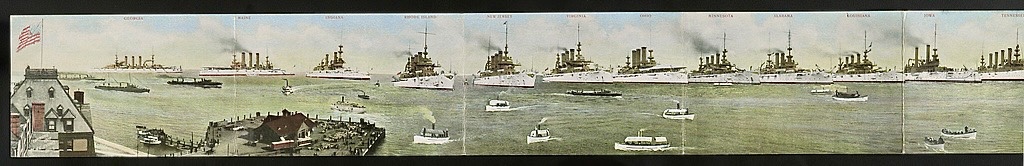

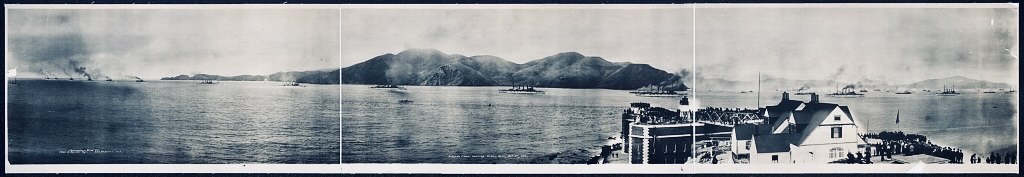

On the morning of December 16, 1907, an impressive armada of warships steamed from Hampton Roads, Virginia to begin a voyage that would take them around the globe. It consisted of sixteen battleships, organized in four squadrons and accompanied by six destroyers and six auxiliary vessels, and carrying 14,000 sailors. The ships’ hulls were painted white, giving the flotilla its name: the Great White Fleet.

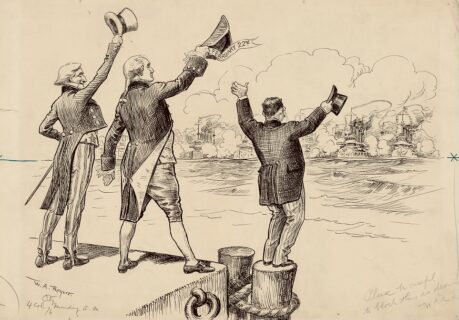

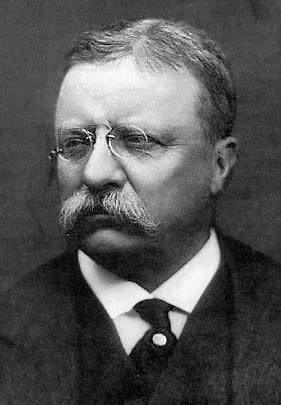

Watching the procession from the yacht Mayflower was the President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt. By all accounts he was grinning ear to ear as the massive battlewagons steamed past, for the president more than any other individual was responsible for this cruise. Although his only time in combat had been on land, at heart Roosevelt had long been a Navy man. He had been fascinated by warships since childhood, and began advocating for naval expansion even during his college years at Harvard. In 1888 the future president struck up a friendship with Alfred Thayer Mahan, naval officer and president of the Naval War College. When, two years later, Mahan published his classic book The Influence of Sea Power upon History, Roosevelt was among the first to endorse it. Mahan’s thesis was that, in the modern age, the dominant power was the one with the largest navy, along with a network of coaling stations to project naval power around the globe. While some historians have claimed that Mahan’s work had a great influence on Roosevelt, it is more appropriate to say that it articulated and solidified what he already believed.

The voyage of the Great White Fleet lasted a total of 434 days. Because the Panama Canal was not yet finished, the first leg took the ships through the Caribbean, down the coast of South America, around the Cape of Good Hope, and north to California. After a two-week stay in San Francisco the armada set out on the second leg of the voyage, further north to Puget Sound. There the ships separated to visit six ports along the Washington coast before returning to San Francisco. There followed another six weeks in San Francisco, followed by a voyage across the Pacific, visiting Hawaii, New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, Japan, and China. The final leg of the journey brought the fleet to Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka), then through the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean Sea, with stops in Sicily and Gibraltar, before heading back across the Atlantic Ocean for home. The armada reached Hampton Roads again on February 22, 1909.

The official stated purpose of the cruise was to provide the U.S. Navy with practice in large-scale fleet operations, something which it had never engaged in before. The movement of an entire fleet of battleships required advanced skills in communication and navigation, particularly as ships had only recently been equipped with radios. The voyage also involved daunting logistical challenges, as the ships burned massive amounts of coal that needed to be supplied either in port, or by colliers—vessels designed to carry coal to ships at sea.

Yet the stated explanation provides only part of the motive for the Great White Fleet’s global cruise. As a number of high-ranking naval officers pointed out, crews could have gained practice in these skills while remaining in home waters. The deeper reason why Roosevelt sent such a large fleet abroad lay more in the realm of international politics than in that of naval affairs. For one, it was an opportunity to win goodwill abroad. It had become common during the 19th century for warships to make “courtesy calls” to friendly nations; in fact, a squadron of German ships had visited New York City five years earlier. The fleet was also able to assist in a humanitarian mission; on December 28, 1908, a major earthquake—the most destructive ever recorded in modern European history—struck Sicily, and U.S. sailors were able to help with rescue and recovery operations when the armada stopped there in early January.

From Roosevelt’s perspective, however, the voyage of the Great White Fleet was first and foremost an opportunity for flexing the country’s new naval muscles. The United States had long been an important economic power; indeed, in the 1890s it had surpassed Great Britain as the nation with the world’s highest GDP, and by 1900 it was the world’s largest producer of steel. Yet before Roosevelt’s presidency the country was not yet considered a major player on the world stage. While U.S. forces had proven capable of defeating the decrepit Kingdom of Spain in 1898, its small army and navy were no match for those of great powers such as Great Britain, France, or Germany. Congress had begun to appropriate significant funds for naval expansion in the 1880s, and by the turn of the century the United States finally had a modern battle fleet. In Roosevelt’s mind, it was time to show it off.

Roosevelt was most concerned about Japan. In the course of less than a half-century Japan had gone from a semi-feudal agrarian country to an industrial power with a modern army and navy. In a letter he wrote on February 8, 1909, as the Great White Fleet was making its way across the Atlantic, the president warned that Japan was the only country he worried that the United States might have to fight in the near future. Victory in the Russo-Japanese War had given Tokyo a substantial empire on the continent of Asia, and the country was set on further expansion. Moreover, the Japanese were proud of their rapid progress, and determined to be treated as equals on the world stage, but “have been bitterly humiliated to find that even their allies, the English, and their friends, the Americans, won’t admit them to association and citizenship, as they admit the least advanced or most decadent European peoples.”[1]

It’s not clear to what extent the voyage of the Great White Fleet impressed the Japanese government, but by all accounts the cruise was a success, at least in a public relations sense. The battleships and their sailors were heartily cheered wherever they went, and, according to historian Mark Albertson, “Relations were fostered with nations that hitherto had been little more than names on a map; while relations with the familiar capitals were enhanced.”[2] But the cruise also revealed weaknesses in the design of some of the battleships, which had, in fact, already been rendered obsolete by the launch of the world’s first “all-big-gun” warship, the Royal Navy’s HMS Dreadnought, in 1906. Furthermore, the voyage illustrated the limitations of the Navy’s logistical ability to support large-scale naval operations. Both of these weaknesses would be addressed in the coming decades, but the Great White Fleet offered a foreshadowing of America’s future as a dominant naval power.

[1] Theodore Roosevelt, The Threat of Japan. https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/trjapan.htm.

[2] Mark Albertson, They’ll Have to Follow You! The Triumph of the Great White Fleet (2007), p. 14.