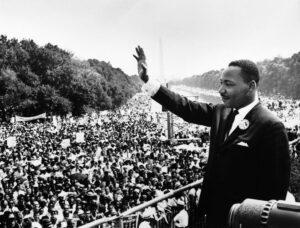

Truman Acts to End Segregation in the Armed Forces

Professor John Moser of Ashland University helps us understand the context and significance of an action President Truman took 65 years ago to begin desegregation of our military.

The 65th Anniversary of Executive Order 9981

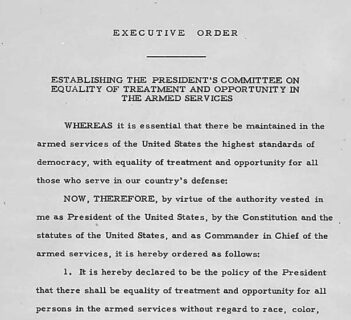

On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which prohibited racial, ethnic, and religious discrimination in the armed forces. It mandated “equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin,” thus paving the way for the end of segregation in the military. Although some all-black units continued to exist through the Korean War, the last of those units was eliminated in 1954.

The origins of Executive Order 9981 lay in an earlier order, 9908, which Truman issued in December 1946. That order authorized the creation of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, charged with investigating the condition of African-Americans in the country and to submit recommendations on how their situation might be improved. The committee’s final report, “To Secure these Rights,” was published in October 1947, and one of its primary recommendations was that the federal government eliminate segregation within those agencies under its control—including the armed forces.

Truman issued Executive Order 9981 for both idealistic and practical reasons. He seems to have been genuinely impressed by the contributions of black soldiers in World War II, and outraged by stories of ill treatment of African-American troops upon their return home. He was moved in particular by the story of Isaac Woodard, a black sergeant in the U.S. Army, who only hours after being discharged was beaten and blinded by a group of police officers in South Carolina. Police Chief Linwood Shull was arrested after the attack, but even after admitting that he had struck Woodard repeatedly in the eyes with his nightstick, he was found not guilty of all charges.

However, there was also some political motivation behind Truman’s order. The president was facing reelection in November 1948, and the conventional wisdom that summer was that the likely Republican challenger, New York Governor Thomas Dewey, was going to have little difficulty unseating him. Truman’s best hope for victory lay in reassembling the old New Deal coalition, which included union labor, farmers, and African-Americans. However, after the death of Roosevelt in 1945 many blacks seemed to be reverting to their old loyalty to the Republican Party. Dewey in particular was an attractive candidate for African-Americans, since as governor of New York he had signed into law the first statewide civil rights legislation in the country. By prohibiting racial discrimination in the armed forces, Truman was able to keep enough of the black vote in the Democratic camp that he was able to secure reelection in 1948.

John Moser, Professor of History Ashland University