West Virginia Achieves Statehood: June 20th, 1863

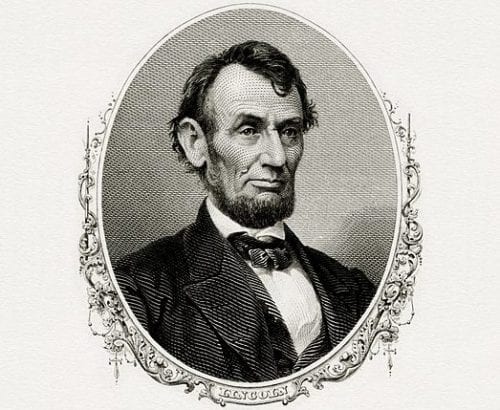

Over the past three years, I have grown a dual enrollment West Virginia History class at my school from only eight students in its first year to almost 50 students enrolled this year. One of my favorite parts of the class is when I dust off my thesis, A Republican Form of Government: Constitutional Crisis and the Creation of West Virginia, and use it to teach my students about the struggles our WV Founders faced while trying to form a brand-new state. During this year’s discussions, it struck me that the WV Statehood Bill was at its heart an antislavery bill that had to pass the muster of radical Republicans in Congress to make it to President Abraham Lincoln’s desk. It is especially poignant that Lincoln signed both the WV Statehood Bill and his final Emancipation Proclamation on the same day—January 1, 1863.

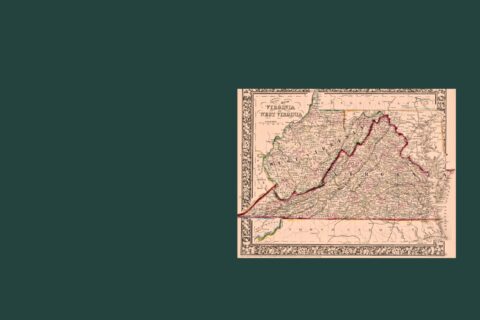

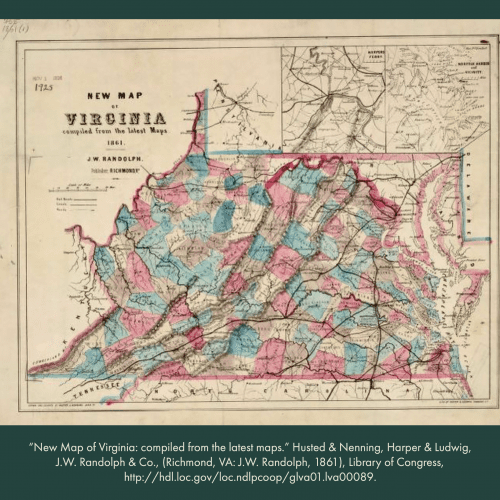

Western Virginians understood the Civil War to center around slavery. Most supported the Union side—not out of sympathy for enslaved people but for economic reasons. In a state politically dominated by eastern plantation owners, most Western Virginians were subsistence farmers, many working land owned by others. The Virginia Land Law of 1779 had given responsibility for attracting settlers to the western region to a few large land companies, through whom speculators had gotten control of much of the land. At the same time, the state constitution gave eastern plantation owners a disproportionate influence in the state assembly. Until 1852, there were property qualifications for voting in Virginia, and those who owned land in multiple counties could cast multiple votes. West Virginians understood that their free labor could not thrive as long they remained yoked to a slaveholding elite who ignored their concerns. When Virginia voted to secede, the northwestern counties of the state organized a separate government which they called the Restored State of Virginia. Now they sought separate statehood.

Federally, the West Virginia Statehood Bill was first debated in the U.S Senate chamber in June 1862. Article IV of the U.S. Constitution requires Congress to confirm all new state constitutions. The WV constitution that arrived in Washington, D.C. barred slaves and freedmen of color from entering the state while protecting the rights of slaveholders in the eastern panhandle and the southern portion of the new state. The latter provision was developed to keep salt industry owners in Kanawha County, plantation owners in the eastern panhandle counties of Berkeley and Jefferson, and those slaveowners residing in southern West Virginia from opposing the West Virginia statehood movement at the ballot box.

The radical Republicans in the Senate, led by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, refused to allow another slave state to enter the Union. Sumner said that “we all know that it takes but very little slavery to make a slave State with all the virus of slavery. Now, by my vote, no new State shall come into this Union and send Senators into this body with this virus. Enough have our public affairs been disturbed, and enough has the Constitution been poisoned. The time has come for the medicine.” The medicine Sumner and his cohorts prescribed was the full abolishment of slavery in all new states admitted to the federal Union. Sumner proposed an amendment to the West Virginia bill requiring an immediate end to slavery in the new state.

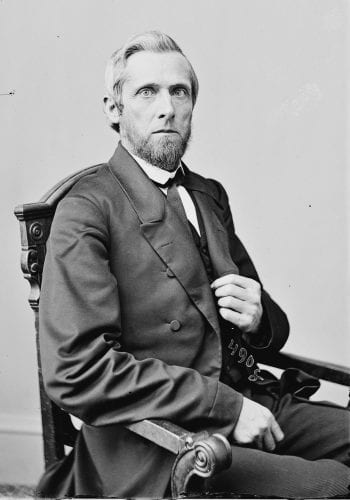

Waitman T. Willey, the U.S. Senator representing the Restored State of Virginia, proposed a compromise known as the Willey Amendment which called for gradual manumission and that all “children of all slaves born within the limits of the said State shall be free.” Willey hailed from Morgantown, VA (now WV) and spent his entire political career as a Republican centrist. He knew that radical Republicans needed to be appeased but he also knew that Congress could not upset the WV slaveholders either. At one point Willey told Sumner that if the radical Republicans made too much of an issue of slavery, then slaveholders would just move their slaves into southern territory once they were eligible for freedom.

The Restored State of Virginia’s other senator, John Carlile—a Harrison County slaveholder, went entirely off the rails when he tried adding twelve Shenandoah Valley counties and almost 32,000 additional slaves to the new state of West Virginia. His amendment was firmly rejected, and the Restored State of Virginia’s legislature asked him to resign from Congress for his actions. According to the 1860 census, there were less than 18,000 slaves in the whole state of West Virginia. As Benjamin Wade of the State of Ohio (Republican) pointed out so truthfully, “Down in the valley they are as pro-slavery as they are on the seacoast, or anywhere else. I do not think it is wise to put them in.” The bill with the Willey Amendment attached passed the Senate by a vote of 23-17. The radical Republicans of the House of Representatives supported the Willey Amendment because it guaranteed the ultimate extinction of slavery in West Virginia. The House passed the bill in December 1862 by a vote of 112 Yeas, 24 Nays, and 46 Not Voting, and was sent to the President for his signature.

The West Virginia statehood bill presented yet another tricky constitutional question for an overstrained Lincoln. On December 23, 1862, he turned to his Cabinet for support and answers so he could decide the bill’s fate. Three Cabinet members, Secretary of State William Seward, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase, and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton all supported West Virginia Statehood while the other three did not support the bill. Stanton argued that the creation of the state of West Virginia would break the “geographical boundary” which had existed between free and slave states. Seward’s letter best exemplifies Lincoln’s philosophy on the Confederate States of America. He stated that he considered these states areas of rebellion without the right to secede and form their own country. He said the states agreed to follow the Constitution when they joined the Union, and the contract could not be broken just because the institution of slavery was under attack. Chase believed statehood to be of “vital importance to their (West Virginia’s) welfare” and that it was “well known that for many years, the people of West Virginia have desired separation on good and substantial grounds.” These substantial grounds included the ideas of universal free manhood suffrage, equal representation in the state government, a tax structure in which eastern Virginians no longer received a tax discount just because they owned slaves, and a state government that respected the contributions of free labor instead of acting only to preserve the institution of slavery.

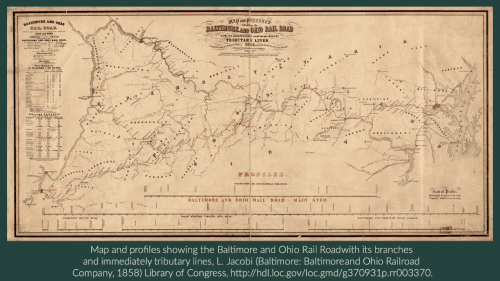

Major news outlets such as The New York Times speculated that Lincoln would veto the West Virginia Statehood Bill; state-level and federal political officials waited impatiently for Lincoln’s final verdict. But Lincoln did not want to lose any part of the Union to the confederacy. He also understood the strategic importance of West Virginia. It was the gateway to the South from the North, and vice versa. Two B & O Railroad lines ran straight across the state from Harper’s Ferry. The original line connected Washington, D.C./Baltimore with Wheeling; the second line went straight across the state through Grafton and Clarksburg to Parkersburg. If the railroad fell to the Confederates, then the entire Midwest would be cut off from the east via the railroad. West Virginia’s system of turnpikes was also critical for the movement of troops.

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln took time to personally share the news of WV statehood with members of the Restored State of Virginia’s Congressional delegation who in turn telegraphed those waiting in the capital at Wheeling. In Lincoln’s final statement on WV statehood, he argued: “We (the Union) can scarcely dispense with the aid of West Virginia in this struggle; much less can we afford to have her against us, in Congress and in the field. . . . Again, the admission of the new State turns that much slave soil to free; and thus, is a certain, and irrevocable encroachment upon the cause of the rebellion. . . .” Not only does this statement announce that turning slave soil to free soil has become one of Lincoln’s priorities; it states that slavery is, in fact, the cause of the war.

The WV Constitutional Convention reconvened on February 12, 1863, and Senator Willey journeyed to Wheeling (Carlile sowed dissension behind the scenes) to convince the delegates that ratifying the Willey Amendment was requisite to statehood. At one point the convention delegates even considered appointing a committee to study compensated manumission, but that was tabled, and the Willey Amendment passed unanimously. The voters of the state also overwhelmingly confirmed the Willey Amendment—by a vote of 28,321 to 572. Lincoln proclaimed on April 20th that WV statehood would be official in 60 days. That explains why West Virginians celebrate WV Day on June 20th each year. Only twelve days after becoming a state, West Virginia sent two cavalry and one infantry regiment to fight at Gettysburg.

Without the work of both U.S. Senator Waitman T. Willey and President Abraham Lincoln, I do not believe that the state of WV would be the 35th star on our star-spangled banner. Nor would have the northwestern counties of VA, by joining the Union, struck such a considerable blow to both the Confederacy and the peculiar institution of slavery. So, when you’re commemorating WV Day this June 20th, take time to remember Senator Willey, the unsung hero of the WV Statehood Movement, and President Lincoln, who recognized WV’s role in defeating the slave power and who proclaimed the state of West Virginia into existence.