The Mysterious Disappearance of Theodora Burr Alston

Do you have a favorite American history story? One that seems too good to be true – one that makes you exclaim – You just can’t make this stuff up! Maybe it’s a story that inspires you, fascinates you, or reminds you why you love history? Maybe it’s a tale of great men or women engaged in extraordinary events. Perhaps it is the triumph of the unsung hero?

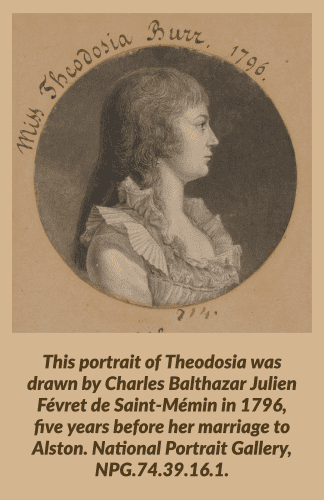

My favorite American history story is about Aaron Burr‘s only child, his daughter Theodosia, whose disappearance at sea in January of 1813 remains a mystery over two hundred years later. I first heard her story from Hazel Flack, my APUSH teacher at Reynolds High School in Winston-Salem, NC, who told it with her usual dramatic flair. It is a dramatic story – one that includes familial love, conspiracy, even piracy.

On the last day of December in 1812, Theodosia Burr Alston, then South Carolina’s First Lady, left Georgetown, SC, on a small schooner named The Patriot. She was sailing to New York to visit her notorious father for the first time in several years. It was a trip expected to take six days. When The Patriot failed to arrive weeks after it was due, Burr, and his son-in-law South Carolina Governor Joseph Alston, assumed the ship had gone down in a winter storm and that all aboard had drowned.

In the following decades, sensational stories about The Patriot and the fate of its crew and passengers made headlines. Several former pirates swore on their deathbed that they had participated in stopping the schooner and forcing its passengers to walk the plank. Two men claimed they had murdered Theodosia before being executed for other crimes. Others claimed she was held captive by pirates, while some claimed her ghost stalked the Outer Banks of North Carolina looking for her father.

At the time of Theodosia’s disappearance, Aaron Burr was attempting to reestablish a law practice in New York. He had returned to the United States in June of 1812 after living in exile for several years following his acquittal on treason charges connected to his role in the so-called Burr Conspiracy. The former Vice-President was accused of attempting to separate the western states from the Union and establishing himself as head of a new nation. He remained reviled by many Americans for killing Alexander Hamilton in their 1804 duel. Still, Burr was surprised to find that some New Yorkers would engage his legal services and treat him with respect. Only one thing remained for Burr in his efforts to rebuild his life – the presence of his daughter Theodosia. Burr enjoyed an unusually close relationship with Theodosia. While in Europe, Burr wrote his daughter up to eight letters a month, sometimes revealing his romantic escapades in shocking detail.

Theodosia had a sense of urgency about seeing her father. Her son and only child, Aaron Burr Alston, died in June of 1812 at age 10 – a victim of malaria, a common illness in the South Carolina low country. Theodosia herself was sick – perhaps from cancer – and desperately wanted to see her father one more time before she died. Burr, Theodosia, and her husband, Joseph Alston, all believed only a visit with her father could comfort her.

Still, Theodosia chose a dangerous time to sail. During the War of 1812, the British Navy stopped American ships at sea, searching for contraband. Although there was nothing suspicious about Theodosia’s trip, the family took extra precautions. Theodosia’s husband wrote a letter for his wife to take with her on her voyage requesting safe passage from the British Navy if they stopped the small craft. Alston hoped the British would take pity on the grieving, terminally ill mother.

The British Navy was not the only thing worrying Burr and his son-in-law. The coast of North Carolina was nicknamed “the graveyard of the Atlantic” because of its dangerous Outer Banks. Ships caught in storms were often pushed onto the shores of the barrier islands. Scavengers, known as “wreckers,” patrolled the Carolina coast. Wreckers sometimes used lanterns to steer unsuspecting captains toward the shore. If the ship became grounded on a sand bar, the wreckers would board it, steal its cargo, and occasionally murder its crew and passengers.

Burr’s close relationship with his daughter was connected to his view of women. Though his reputation was that of a notorious womanizer, Burr had read Mary Wollstonecraft’s book, Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which convinced him of something he said few of his contemporaries believed, “that women have souls.” He pledged to educate his daughter the same way he would educate a son. Young Theodosia learned Latin, French, Roman history, philosophy, and mathematics. Aaron pushed Theodosia to excel – writing lengthy assessments of her progress and detailed descriptions of the reading he expected her to complete.

Similarly, Theodosia’s mother, also named Theodosia, was well-read and well educated. It was the older Theodosia’s intellectual gifts that Burr found charming when he met Theodosia Bartow Prevost while serving in the American army during the Revolutionary War. She was ten years older than Burr and married to a British officer, Jacques Marcus Prevost. Still, Mrs. Prevost and Burr developed a close friendship, despite their age difference. When Prevost died during the war, Burr and Theodosia quickly married and quickly produced the daughter Burr would become closely attached to.

In 1794, Theodosia Burr became her father’s preferred hostess upon her mother’s death, though she was only ten years old. By the time she was a teenager, she was regularly entertaining her father’s political friends and associates, including James Madison, Joseph Brandt, and Alexander Hamilton, the man destined to become Burr’s bitter political rival. Some believed the younger Theodosia to be the best-educated woman in America during the 1790s.

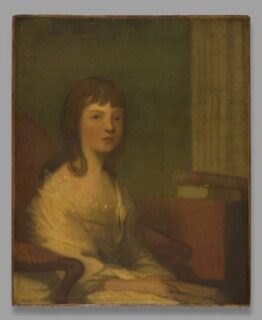

The mystery of Theodosia and The Patriot took a strange turn in 1869, when a North Carolina physician, Dr. William Poole, treated a woman in Nags Head while vacationing on the Outer Banks. She told Poole that her only valuable possession was a portrait of a young woman her first husband took from a wrecked ship during the War of 1812. She gave Poole the unsigned portrait as payment for his services. Poole was familiar with the mystery of Theodosia’s disappearance. He became convinced that the portrait’s subject was Theodosia, who was taking it to her father as a gift when she disappeared. The painting, owned by the Lewis Walpole Museum in Farmington, CT, is unsigned, and the subject is unnamed.

Many years ago, I told Theodosia’s story to my son’s 8th-grade class. I told them that historians were in search of what really happened, and I challenged the 8th graders to think of questions historians would ask as they tried to determine what happened to Theodosia and whether or not the woman in the Nags Head Portrait was really her. The students came up with some great questions, eagerly vying to exhaust the possible explanations. One student asked; “How do we know if the British stopped The Patriot?” Another youngster asked whether we knew if there were records of storms on the east coast in 1813. Then a student asked who might have painted the portrait. After all, only a relative handful of artists in America at that time had the talent to complete such a painting. That prompted a student to ask if the subject posed for the artist? If so, where and when did the sitting take place? One central unanswered question arose. – If the woman in the portrait is Theodosia Burr Alston, and if she died when The Patriot sank, how did the painting survive a winter storm at sea to wash up undamaged on the North Carolina coast? Could the story of pirates actually be a better explanation?

Historians have documented a winter storm on the Carolina coast in January of 1813. Ships’ logs from vessels patrolling those waters in 1813 do not record The Patriot being stopped by the British Navy. Historians have suggested that one or two artists may have visited Charleston, SC around the time a portrait of Theodosia would have been completed for her to take to Aaron Burr as a gift. Speculation seems to center on John Vanderlyn as the most likely candidate. Still, no one can say for sure whether the Nags Head Portrait is Theodosia or not. The mystery endures.

Further reading: Theodosia: Theodosia Burr Alston: Portrait of a Prodigy by Richard N Cote