Introduction

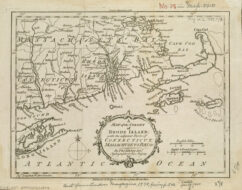

How to treat the indigenous people became an issue as soon as the Spanish arrived in the Western Hemisphere. In a letter written soon after his first voyage (Document 1), Christopher Columbus explained how he dealt with the natives and revealed his and Spain’s religious motive for exploring what he conceived to be, in explicitly religious terms (Document 2) a New World. In addition to the converts to Catholicism that Columbus mentions, the Spanish sought gold. What means were allowable in pursuit of these ends? By what authority did the Spanish make claims on the native people and their land? The Requerimiento (Document 3) provided the official answer to these questions.

Whatever Spanish justifications, the Spanish conquistadores or conquerors proved brutal and rapacious as the conquest continued. The authorities in Madrid did not approve. For example, laws regulating conduct in the conquest were promulgated in 1513 and 1542 (the latter partially repealed in 1545 because of opposition). They relieved Christopher Columbus of command over land he had discovered in part because of his brutality toward both Spanish settlers and the indigenous people. Columbus complained of the injustice of his removal (Document 2), by emphasizing that the New World was not like Spain but was an uncivilized, lawless territory. Francisco de Vitoria, on the contrary, (Document 4) sought to mitigate the harshness of the conquest by arguing that law—civil, natural and divine—should prevail everywhere. He argued for limits on what could legitimately be done to the indigenous people. In doing so, he helped develop just war theory. Despite de Vitoria’s arguments, distance from Madrid, limited means of communication, and the need for colonial wealth reduced the ability and willingness of Spain’s monarchs to control what was done in their name thousands of miles away from their palaces. Bartolomé de las Casas (Document 5) describes the consequences of the Spanish conquest.

Documents in this chapter are available separately by following the hyperlinks below:

- Christopher Columbus to Raphael Sanchez, 1493

- Christopher Columbus to Doña Juana de Torres, 1500

- Juan López de Palacios Rubios, Requerimiento, 1513

- Francisco de Vitoria, De Indis, 1532

- Bartolomé de Las Casas, A Short Description of the Destruction of the Indies, 1542

Christopher Columbus to Raphael Sanchez, March 14, 1493[1]

A Letter addressed to the noble Lord Raphael Sanchez, Treasurer to their most invincible Majesties, Ferdinand and Isabella, King and Queen of Spain, by Christopher Columbus

. . . In that island also which I have before said we name Española, there are mountains of very great size and beauty, vast plains, groves, and very fruitful fields, admirably adapted for tillage, pasture, and habitation. The convenience and excellence of the harbors in this island, and the abundance of the rivers, so indispensable to the health of man, surpass anything that would be believed by one who had not seen it. The trees, herbage, and fruits of Española are very different from those of Juana, and moreover it abounds in various kinds of spices, gold, and other metals. The inhabitants of both sexes in this island, and in all the others which I have seen, or of which I have received information, go always naked as they were born, with the exception of some of the women, who use the covering of a leaf, or small bough, or an apron of cotton which they prepare for that purpose. None of them, as I have already said, are possessed of any iron, neither have they weapons, being unacquainted with, and indeed incompetent to use them, not from any deformity of body (for they are well-formed), but because they are timid and full of fear. They carry however in lieu of arms, canes dried in the sun, on the ends of which they fix heads of dried wood sharpened to a point, and even these they dare not use habitually; for it has often occurred when I have sent two or three of my men to any of the villages to speak with the natives, that they have come out in a disorderly troop, and have fled in such haste at the approach of our men, that the fathers forsook their children and the children their fathers. This timidity did not arise from any loss or injury that they had received from us; for, on the contrary, I gave to all I approached whatever articles I had about me, such as cloth and many other things, taking nothing of theirs in return: but they are naturally timid and fearful. As soon however as they see that they are safe, and have laid aside all fear, they are very simple and honest, and exceedingly liberal with all they have; none of them refusing anything he may possess when he is asked for it, but on the contrary inviting us to ask them. They exhibit great love towards all others in preference to themselves: they also give objects of great value for trifles, and content themselves with very little or nothing in return. I however forbad that these trifles and articles of no value (such as pieces of dishes, plates, and glass, keys, and leather straps) should be given to them, although if they could obtain them, they imagined themselves to be possessed of the most beautiful trinkets in the world. It even happened that a sailor received for a leather strap as much gold as was worth three golden nobles, and for things of more trifling value offered by our men, especially newly coined blancas, or any gold coins, the Indians would give whatever the seller required; as, for instance, an ounce and a half or two ounces of gold, or thirty or forty pounds of cotton, with which commodity they were already acquainted. Thus they bartered, like idiots, cotton and gold for fragments of bows, glasses, bottles, and jars; which I forbad as being unjust, and myself gave them many beautiful and acceptable articles which I had brought with me, taking nothing from them in return; I did this in order that I might the more easily conciliate them, that they might be led to become Christians, and be inclined to entertain a regard for the King and Queen, our Princes and all Spaniards, and that I might induce them to take an interest in seeking out, and collecting, and delivering to us such things as they possessed in abundance, but which we greatly needed. They practice no kind of idolatry, but have a firm belief that all strength and power, and indeed all good things, are in heaven, and that I had descended form thence with these ships and sailors, and under this impression was I received after they had thrown aside their fears. Nor are they slow or stupid, but of very clear understanding; and those men who have crossed to the neighboring islands give an admirable description of everything they observed; but they never saw any people clothed, nor any ships like ours. On my arrival at that sea, I had taken some Indians by force from the first island that I came to, in order that they might learn our language, and communicate to us what they knew respecting the country; which plan succeeded excellently, and was a great advantage to us, for in a short time, either by gestures and signs, or by words, we were enabled to understand each other. These men are still traveling with me, and although they have been with us now a long time, they continue to entertain the idea that I have descended from heaven; and on our arrival at any new place they published this, crying out immediately with a loud voice to the other Indians, “Come, come and look upon beings of a celestial race”: upon which both women and men, children and adults, young men and old, when they got rid of the fear they at first entertained, would come out in throngs, crowding the roads to see us, some bringing food, others drink, with astonishing affection and kindness. . . . In all these islands there is no difference of physiognomy, of manners, or of language, but they all clearly understand each other, a circumstance very propitious for the realization of what I conceive to be the principal wish of our most serene King, namely, the conversion of these people to the holy faith of Christ, to which indeed, as far as I can judge, they are very favorable and well-disposed.

Back to TopChristopher Columbus to Doña Juana de Torres, 1500[2]

Most Virtuous Lady:

Though my complaint of the world is new, its habit of ill-using is very ancient. I have had a thousand struggles with it, and have thus far withstood them all, but now neither arms nor counsels avail me and it cruelly keeps me under water. Hope in the creator of all men sustains me; His help was always very ready; on another occasion, and not long ago, when I was still more overwhelmed, He raised me with his right arm, saying, O Man of little faith, arise, it is I; be not afraid.[3]

I came with so much cordial affection to serve these princes, and have served them with such service, as has never been heard of or seen.

Of the new heaven and earth which our Lord made, when Saint John was writing Apocalypse,[4] after what was spoken by the mouth of Isaiah,[5] he made me the messenger, and showed me where it lay. In all men there was disbelief, but to the Queen my Lady He gave the spirit of understanding, and great courage, and made her heiress of all, as a dear and much loved daughter. I went to take possession of all this in her royal name. They sought to make amends to her for the ignorance they had all shown by passing over their little knowledge, and talking of obstacles and expenses. Her Highness, on the other hand, approved of it, and supported as far as she was able. . . .

They judge me over there as they would a Governor who had gone to Sicily, or to a city or town placed under regular government, and where the laws can be observed in their entirety without fear of ruining everything; and I am greatly injured thereby. I ought to be judged as a Captain who went from Spain to the Indes to conquer a numerous and warlike people, whose customs and religion are very contrary to ours; who live in rocks and mountains, without fixed settlements, and not like ourselves; and where, by the divine will, I have placed under the dominion of the King and Queen, our sovereigns, another world, through which Spain, which was reckoned a poor country, has become the richest. I ought to be judged as a Captain who for such a long time up to this day has borne arms without laying them aside for an hour, and by gentlemen adventurers and by customs and not by letters, unless they were Greeks or Romans, or others of modern times of whom there are so many and such noble examples in Spain; or otherwise I receive great injury, because in the Indes there is neither town nor settlement. . . .

Back to TopJuan López de Palacios Rubios, Requerimiento, 1513[6]

On the part of the King, Don Fernando, and of Doña Juana, his daughter, Queen of Castile and León, subduers of the barbarous nations, we their servants notify and make known to you, as best we can, that the Lord our God, Living and Eternal, created the Heaven and the Earth, and one man and one woman, of whom you and we, all the men of the world, were and are descendants, and all those who came after us. But, on account of the multitude which has sprung from this man and woman in the five thousand years since the world was created, it was necessary that some men should go one way and some another, and that they should be divided into many kingdoms and provinces, for in one alone they could not be sustained.

Of all these nations God our Lord gave charge to one man, called St. Peter, that he should be Lord and Superior of all the men in the world, that all should obey him, and that he should be the head of the whole human race, wherever men should live, and under whatever law, sect, or belief they should be; and he gave him the world for his kingdom and jurisdiction.

And he commanded him to place his seat in Rome as the spot most fitting to rule the world from; but also he permitted him to have his seat in any other part of the world, and to judge and govern all Christians, Moors [Muslims], Jews, Gentiles, and all other sects. This man was called Pope, as if to say, Admirable Great Father and Governor of men. The men who lived in that time obeyed that St. Peter and took him for Lord, King, and Superior of the universe; so also they have regarded the others who after him have been elected to the pontificate, and so has it been continued even till now and will continue till the end of the world.

One of these Pontiffs [popes] who succeeded that St. Peter as Lord of the world, in the dignity and seat which I have before mentioned, made donation of these isles and Tierra-firme to the aforesaid King and Queen and to their successors,[7] our lords, with all that there are in these territories, as is contained in certain writings which passed upon the subject as aforesaid, which you can see if you wish.

So their Highnesses are kings and lords of these islands and land of Tierra-firme by virtue of this donation: and some islands, and indeed almost all those to whom this has been notified, have received and served their Highnesses, as lords and kings, in the way that subjects ought to do, with good will, without any resistance, immediately, without delay, when they were informed of the aforesaid facts. And also they received and obeyed the priests whom their Highnesses sent to preach to them and to teach them our Holy Faith; and all these, of their own free will, without any reward or condition, have become Christians, and are so, and their Highnesses have joyfully and benignantly received them, and also have commanded them to be treated as their subjects and vassals; and you too are held and obliged to do the same. Wherefore, as best we can, we ask and require you that you consider what we have said to you, and that you take the time that shall be necessary to understand and deliberate upon it, and that you acknowledge the Church as the Ruler and Superior of the whole world, and the high priest called Pope, and in his name the King and Queen Doña Juana our lords, in his place, as superiors and lords and kings of these islands and this Tierra-firme by virtue of the said donation, and that you consent and give place that these religious fathers should declare and preach to you the aforesaid.

If you do so, you will do well, and that which you are obliged to do to their Highnesses, and we in their name shall receive you in all love and charity, and shall leave you, your wives, and your children, and your lands, free without servitude, that you may do with them and with yourselves freely that which you like and think best, and they shall not compel you to turn Christians, unless you yourselves, when informed of the truth, should wish to be converted to our Holy Catholic Faith, as almost all the inhabitants of the rest of the islands have done. And, besides this, their Highnesses award you many privileges and exemptions and will grant you many benefits.

But, if you do not do this, and maliciously make delay in it, I certify to you that, with the help of God, we shall powerfully enter into your country, and shall make war against you in all ways and manners that we can, and shall subject you to the yoke and obedience of the Church and of their Highnesses; we shall take you and your wives and your children, and shall make slaves of them, and as such shall sell and dispose of them as their Highnesses may command; and we shall take away your goods, and shall do you all the mischief and damage that we can, as to vassals who do not obey, and refuse to receive their lord, and resist and contradict him; and we protest that the deaths and losses which shall accrue from this are your fault, and not that of their Highnesses, or ours, nor of these cavaliers who come with us. And that we have said this to you and made this Requisition, we request the notary here present to give us his testimony in writing, and we ask the rest who are present that they should be witnesses of this Requisition.

Back to TopFrancisco de Vitoria, De Indis, 1532[8]

The First Reconsideration[9] of the Reverend Father, Brother Franciscus De Victoria, on the Indians Lately Discovered.

First Section . . .

Fourth, . . . I ask first whether the aborigines in question were true owners in both private and public law before the arrival of the Spaniards; that is, whether they were true owners of private property and possessions and also whether there were among them any who were the true princes and overlords of others. . . .

. . . [I]f the aborigines had not dominion, it would seem that no other cause is assignable therefor except that they were sinners or were unbelievers or were witless or irrational. . . .

[Appealing to various authorities, de Vitoria argues that the aborigines cannot be deprived of their property because they are sinners.]. . . .

23. . . The Indian aborigines are not barred on this ground [lack of reason] from the exercise of true dominion. This is proved from the fact that the true state of the case is that they are not of unsound mind, but have, according to their kind, the use of reason. This is clear, because there is a certain method in their affairs, for they have polities which are orderly arranged and they have definite marriage and magistrates, overlords, laws, and workshops, and a system of exchange, all of which call for the use of reason; they also have a kind of religion. Further, they make no error in matters which are self-evident to others; this is witness to their use of reason. Also, God and nature are not wanting in the supply of what is necessary in great measure for the race. Now, the most conspicuous feature of man is reason, and power is useless which is not reducible to action. Also, it is through no fault of theirs that these aborigines have for many centuries been outside the pale of salvation, in that they have been born in sin and void of baptism and the use of reason whereby to seek out the things needful for salvation. Accordingly I for the most part attribute their seeming so unintelligent and stupid to a bad and barbarous upbringing, for even among ourselves we find many peasants who differ little from brutes.

24. The upshot of all the preceding is, then, that the aborigines undoubtedly had true dominion in both public and private matters, just like Christians, and that neither their princes nor private persons could be despoiled of their property on the ground of their not being true owners. It would be harsh to deny to those, who have never done any wrong, what we grant to Saracens and Jews, who are the persistent enemies of Christianity. We do not deny that these latter peoples are true owners of their property, if they have not seized lands elsewhere belonging to Christians.

It remains to reply to the argument . . . that the aborigines in question seem to be slaves by nature because of their incapability of self-government. My answer to this is that Aristotle certainly did not mean to say that such as are not over-strong mentally are by nature subject to another’s power and incapable of dominion alike over themselves and other things; for this is civil and legal slavery, wherein none are slaves by nature. Nor does the Philosopher mean that, if any by nature are of weak mind, it is permissible to seize their patrimony and enslave them and put them up for sale; but what he means is that by defect of their nature they need to be ruled and governed by others and that it is good for them to be subject to others, just as sons need to be subject to their parents until of full age, and a wife to her husband. . . .

Second Section

It being premised, then, that the Indian aborigines are or were true owners, it remains to inquire by what title the Spaniards could have come into possession of them and their country. . . .

15. Sixth proposition: Although the Christian faith may have been announced to the Indians with adequate demonstration and they have refused to receive it, yet this is not a reason which justifies making war on them and depriving them of their property. This conclusion is definitely stated by St. Thomas (Secunda Secundae, qu. 10, art. 8), where he says that unbelievers who have never received the faith, like Gentiles and Jews, are in no wise to be compelled to do so. This is the received conclusion of the doctors alike in the canon law and the civil law. The proof lies in the fact that belief is an operation of the will. Now, fear detracts greatly from the voluntary (Ethics, bk. 3), and it is a sacrilege to approach under the influence of servile fear as far as the mysteries and sacraments of Christ. . . .

Our proposition receives further proof from the use and custom of the Church. For never have Christian Emperors, who had as advisors the most holy and wise Pontiffs, made war on unbelievers for their refusal to accept the Christian religion. Further, war is no argument for the truth of the Christian faith. Therefore the Indians cannot be induced by war to believe, but rather to feign belief and reception of the Christian faith, which is monstrous and a sacrilege. . . .

Another, and a fifth title[10] is seriously put forward, namely, the sins of these Indian aborigines. For it is alleged that, though their unbelief or their rejection of the Christian faith is not a good reason for making war on them, yet they may be attacked for other mortal sins which (so it is said) they have in numbers, and those very heinous. . . .

16. I, however, assert the following proposition: Christian princes cannot, even by the authorization of the Pope, restrain the Indians from sins against the law of nature or punish them because of those sins. My first proof is that the writers in question build on a false hypothesis, namely, that the Pope has Jurisdiction over the Indian aborigines, as said above. . . .

Further, the Pope cannot make war on Christians on the ground of their being fornicators or thieves or, indeed, because they are sodomites; nor can he on that ground confiscate their land and give it to other princes; were that so, there would be daily changes of kingdoms, seeing that there are many sinners in every realm. And this is confirmed by the consideration that these sins are more heinous in Christians, who are aware that they are sins, than in barbarians, who have not that knowledge. Further, it would be a strange thing that the Pope, who cannot make laws for unbelievers, can yet sit in judgment and visit punishment upon them.

A further and convincing proof is the following: The aborigines in question are either bound to submit to the punishment awarded to the sins in question or they are not. If they are not bound, then the Pope cannot award such punishment. If they are bound, then they are bound to recognize the Pope as lord and lawgiver. Therefore, if they refuse such recognition, this in itself furnishes a ground for making war on them, which, however, the writers in question deny, as said above. And it would indeed be strange that the barbarians could with impunity deny the authority and jurisdiction of the Pope, and yet that they should be bound to submit to his award. Further, they who are not Christians cannot be subjected to the judgment of the Pope, for the Pope has no other right to condemn or punish them than as vicar of Christ. But, the writers in question admit—both Innocent and Augustinus of Ancona, and the Archbishop and Sylvester, too—that they cannot be punished because they do not receive Christ. Therefore [they cannot be punished] because they do not receive the judgment of the Pope, for the latter presupposes the former.

The insufficiency alike of this present title and of the preceding one, is shown by the fact that, even in the Old Testament, where much was done by force of arms, the people of Israel never seized the land of unbelievers either because they were unbelievers or idolaters or because they were guilty of other sins against nature (and there were people guilty of many such sins, in that they were idolaters and committed many other sins against nature, as by sacrificing their sons and daughters to devils), but because of either a special gift from God or because their enemies had hindered their passage or had attacked them. . . .

. . . There remains another, a sixth title, which is put forward, namely, by voluntary choice. For on the arrival of the Spaniards we find them declaring to the aborigines how the King of Spain has sent them for their good and admonishing them to receive and accept him as lord and king; and the aborigines replied that they were content to do so. . . . I, however, assert the proposition that this title, too, is insufficient. This appears, in the first place, because fear and ignorance, which vitiate every choice, ought to be absent. But they were markedly operative in the cases of choice and acceptance under consideration, for the Indians did not know what they were doing; nay, they may not have understood what the Spaniards were seeking. Further, we find the Spaniards seeking it in armed array from an unwarlike and timid crowd. Further, inasmuch as the aborigines, as said above, had real lords and princes, the populace could not procure new lords without other reasonable cause, this being to the hurt of their former lords. Further, on the other hand, these lords themselves could not appoint a new prince without the assent of the populace. Seeing, then, that in such cases of choice and acceptance as these there are not present all the requisite elements of a valid choice, the title under review is utterly inadequate and unlawful for seizing and retaining the provinces in question.

There is a seventh title which can be set up, namely, by special grant from God. For some (I know not who) assert that the Lord by His especial judgment condemned all the barbarians in question to perdition because of their abominations and delivered them into the hands of the Spaniards, just as of old He delivered the Canaanites into the hands of the Jews. I am loath to dispute hereon at any length, for it would be hazardous to give credence to one who asserts a prophecy against the common law and against the rules of Scripture, unless his doctrine were confirmed by miracles. Now, no such are adduced by prophets of this type. Further, even assuming that it is true that the Lord had determined to bring the barbarians to perdition, it would not follow, therefore, that he who wrought their ruin would be blameless, any more than the Kings of Babylon who led their army against Jerusalem and carried away the children of Israel into captivity were blameless, although in actual fact all of this was by the especial providence of God, as had often been foretold to them. . . .

Let this suffice about false and inadequate titles to seize the lands of the Indians. . . .

Third Section . . .

6. Fifth proposition: If the Indian natives wish to prevent the Spaniards from enjoying any of their above-named rights under the law of nations, for instance, trade or other above-named matter, the Spaniards ought in the first place to use reason and persuasion in order to remove scandal and ought to show in all possible methods that they do not come to the hurt of the natives, but wish to sojourn as peaceful guests and to travel without doing the natives any harm;—and they ought to show this not only by word, but also by reason, according to the saying, “It behoveth the prudent to make trial of everything by words first.” But if, after this recourse to reason, the barbarians decline to agree and propose to use force, the Spaniards can defend themselves and do all that consists with their own safety, it being lawful to repel force by force. . . .

It is, however, to be noted that the natives being timid by nature and in other respects dull and stupid, however much the Spaniards may desire to remove their fears and reassure them with regard to peaceful dealings with each other, they may very excusably continue afraid at the sight of men strange in garb and armed and much more powerful than themselves. And therefore, if, under the influence of these fears, they unite their efforts to drive out the Spaniards or even to slay them, the Spaniards might, indeed, defend themselves but within the limits of permissible self-protection, and it would not be right for them to enforce against the natives any of the other rights of war (as, for instance, after winning the victory and obtaining safety, to slay them or despoil them of their goods or seize their cities), because on our hypothesis the natives are innocent and are justified in feeling afraid. Accordingly, the Spaniards ought to defend themselves, but so far as possible with the least damage to the natives, the war being a purely defensive one.

There is no inconsistency, indeed, in holding the war to be a just war on both sides, seeing that on one side there is right and on the other side there is invincible ignorance. For instance, just as the French hold the province of Burgundy with demonstrable ignorance, in the belief that it belongs to them, while our Emperor’s right to it is certain, and he may make war to regain it, just as the French may defend it, so it may also befall in the case of the Indians—a point deserving careful attention. For the rights of war which may be invoked against men who are really guilty and lawless differ from those which may be invoked against the innocent and ignorant, just as the scandal of the Pharisees is to be avoided in a different way from that of the self-distrustful and weak.

7. Sixth proposition: If after recourse to all other measures, the Spaniards are unable to obtain safety as regards the native Indians, save by seizing their cities and reducing them to subjection, they may lawfully proceed to these extremities. . . .

8. Seventh proposition: If, after the Spaniards have used all diligence, both in deed and in word, to show that nothing will come from them to interfere with the peace and well-being of the aborigines, the latter nevertheless persist in their hostility and do their best to destroy the Spaniards, then they can make war on the Indians, no longer as on innocent folk, but as against forsworn enemies, and may enforce against them all the rights of war, despoiling them of their goods, reducing them to captivity, deposing their former lords and setting up new ones, yet withal with observance of proportion as regards the nature of the circumstances and of the wrongs done to them. . . .

18. There is another title which can indeed not be asserted, but brought up for discussion, and some think it a lawful one. I dare not affirm it at all, nor do I entirely condemn it. It is this: Although the aborigines in question are (as has been said above) not wholly unintelligent, yet they are little short of that condition, and so are unfit to found or administer a lawful State up to the standard required by human and civil claims. . . . It might, therefore, be maintained that in their own interests the sovereigns of Spain might undertake the administration of their country, providing them with prefects and governors for their towns, and might even give them new lords, so long as this was clearly for their benefit. I say there would be some force in this contention. . . . The same principle seems to apply here to them as to people of defective intelligence; and indeed they are no whit or little better than such so far as self-government is concerned, or even than the wild beasts, for their food is not more pleasant and hardly better than that of beasts. Therefore their governance should in the same way be entrusted to people of intelligence. . . . And surely this might be founded on the precept of charity, they being our neighbors and we being bound to look after their welfare. Let this, however, as I have already said, be put forward without dogmatism and subject also to the limitation that any such interposition be for the welfare and in the interests of the Indians and not merely for the profit of the Spaniards. For this is the respect in which all the danger to soul and salvation lies. And herein some help might be gotten from the consideration, referred to above, that some are by nature slaves, for all the barbarians in question are of that type and so they may in part be governed as slaves are.

The Second Reconsideration of the Reverend Father, Brother Franciscus De Vitoria, On The Indians, or On The Law of War Made by the Spaniards on the Barbarians.

Inasmuch as the seizure and occupation of those lands of the barbarians whom we style Indians can best, it seems, be defended under the law of war, I propose to supplement the foregoing discussion of the titles, some just and some unjust, which the Spaniards may allege for their hold on the lands in question, by a short discussion of the law of war, so as to give more completeness to that [first] reconsideration [relectio]. . . .

13. Fourth proposition: There is a single and only just cause for commencing a war, namely, a wrong received. . . .

14. Fifth proposition: Not every kind and degree of wrong can suffice for commencing a war. . . . As, then, the evils inflicted in war are all of a severe and atrocious character, such as slaughter and fire and devastation, it is not lawful for slight wrongs to pursue the authors of the wrongs with war, seeing that the degree of the punishment ought to correspond to the measure of the offence (Deuteronomy, ch. 25). . . .

37. . . . Great attention, however, must be paid to the point already taken, namely, the obligation to see that greater evils do not arise out of the war than the war would avert. . . . [I]t is never right to slay the guiltless, even as an indirect and unintended result, except when there is no other means of carrying on the operations of a just war, according to the passage (St. Matthew, ch. 13) “Let the tares grow, lest while ye gather up the tares ye root up also the wheat with them.” . . .

42. Assuming the unlawfulness of the slaughter of children and other innocent parties, is it permissible, at any rate, to carry them off into captivity and slavery? This can be cleared up in a single proposition, namely: It is in precisely the same way permissible to carry the innocent off into captivity as to despoil them, liberty and slavery being included among the good things of Fortune. And so when a war is at that pass that the indiscriminate spoliation of all enemy-subjects alike and the seizure of all their goods are justifiable, then it is also justifiable to carry all enemy-subjects off into captivity, whether they be guilty or guiltless. And inasmuch as war with pagans is of this type, seeing that it is perpetual and that they can never make amends for the wrongs and damages they have wrought, it is indubitably lawful to carry off both the children and the women of the Saracens into captivity and slavery. But inasmuch as, by the law of nations, it is a received rule of Christendom that Christians do not become slaves in right of war, this enslaving is not lawful in a war between Christians; but if it is necessary having regard to the end and aim of war, it would be lawful to carry away even innocent captives, such as children and women, not indeed into slavery, but so that we may receive a money-ransom for them. This, however, must not be pushed beyond what the necessity of the war may demand and what the custom of lawful belligerents has allowed.

Back to TopBartolomé de Las Casas, A Short Description of the Destruction of the Indies, 1542[11]

. . . The Fifth Kingdom[12] was Hiquey, over which Queen Hiquanama, an elderly Princess, whom the Spaniards Crucified, presided and governed. I saw an infinite number of these people burned, and dismembered, and racked with various torments, and of those who survived these matchless evils who were then enslaved. But because so much might be said concerning the killing and destruction of these people, as cannot without great difficulty be written (nor do I conceive that one part of 1,000 that is here contained can be fully displayed) I will only add one remark more about the previously mentioned wars, and declare upon my conscience, that notwithstanding all the above-named injustice, profligate enormities and other crimes which I omit, (though sufficiently known to me) the Indians did not, nor was it in their power to, give [the Spaniards] any cause for these crimes, any more than the pious religious living in a well-regulated Monastery could give a sacrilegious villain any reason to deprive them of their goods and life. No was there any cause for the Spaniards to enslave in perpetuity those who survived the initial massacre. I really believe and am satisfied by certain undeniable conjectures, that at the very time when all these outrages were committed in this Isle, the Indians were not so much guilty of one single mortal sin of commission against the Spaniards, that might deserve from anyone such revenge. And as for those sins, the punishment of which God reserves to himself, such as the immoderate desire of revenge, hatred, envy or inward rancor of spirit, to which [the Indians] might be led against such capital enemies as the Spaniards, I judge that very few of [the Indians] can justly be accused of them; for their impetuosity and vigor, I know, to be inferior to that of children of ten or twelve years of age. And I can assure you, that the Indians had every just cause to wage war against the Spaniards, and the Spaniards on the contrary never waged a just war against them, but only what was more injurious and groundless than any undertaken by the worst of Tyrants. This was true of all their actions in America.

The wars being over, and the inhabitants all swept away, the Spaniards divided among themselves the young men, women, and children, one taking thirty, another forty, to this man one hundred were given, to the other two hundred. The more one was in favor with the domineering tyrant (whom they styled Governor), the more slaves he got, under the pretense, and on the condition, that he should instruct the slave in the Catholic religion. Yet, those Spaniards to whom the Indians were given were themselves for the most part idiotic, cruel, avaricious, and infected with all sorts of vices. And this was the great care they had of [the Indians]: they sent the men to the mines to dig for gold, which is an intolerable labor; the women they turned to tilling and manuring the ground, which is drudgery even to men of the strongest and most robust constitutions. They gave them nothing else to eat but wild grasses and other such insubstantial nutriment, so that the milk of nursing women dried up, which meant that recently born infants all died. Since the females were separated from and did not live with the men, there were no new births among them. The men died in the mines, starved and oppressed with labor, and the women perished in the fields, broken from the same evils and calamities. Thus, the infinite number of inhabitants that formerly peopled this island were exterminated and dwindled away to nothing. They were compelled to carry burdens of eighty or one hundred pound weight a hundred or two hundred miles. They had to carry the Spaniards on their shoulders in a carriage or a kind of bed woven by the Indians. In truth they made use of them as beasts to carry baggage on their journeys, so much so that it frequently happened that the shoulders and backs of the Indians were deeply marked with sores, just as happens with animals that carry heavy burdens. It would take a long time, and many reams of paper to describe the slashes with whips, blows with staves, beatings and curses, and all the other torments they suffered during these backbreaking journeys, and even then it would only create horror and dismay in the reader.

But it is true that the desolation of these islands began only with the death of the most Serene Queen Isabella, about the year 1504. Before that time very few of the provinces situated in that island [Hispaniola] were oppressed or spoiled with unjust wars, or violated with general devastation as they were afterwards. Most if not all these things were concealed and masked from the Queen’s knowledge (whom I hope God hath crowned with Eternal Glory) for she was transported with fervent and wonderful zeal, in fact, almost Divine desire for the salvation and preservation of these people, as we have seen with our own eyes and cannot easily forget.

Take this also for a general rule, that no matter which coast in the Americas the Spaniards were landed on, they carried out the same cruelties, slaughters, tyrannies and detestable oppressions on the most innocent Indian nations. The more time they spent in the Americas the more they diverted themselves with new ways of tormenting the Indians, improving in barbarism and cruelty. As a consequence, God, incensed at them, allowed them to fall into complete wickedness.

Back to Top- 1. Writings of Christopher Columbus: Descriptive of the Discovery and Occupation of the New World, Paul Leicester Ford, ed. (New York: C. L. Webster, 1892), 33–51.

- 2. Letter of Columbus to the Nurse of Prince John, American Journeys Collection, Document No. AJ-067, Wisconsin Historical Society Digital Library and Archives, Wisconsin Historical Society, 2003.

- 3. Matthew 14:31

- 4. Revelation 21:1

- 5. Isaiah 65:17

- 6. Juan López de Palacios Rubios (1450–1524) was a Spanish jurist. The text may be found at https://goo.gl/fQBpta

- 7. The Papal Bull or Decree “Inter caetera” (May 4, 1493) granted certain territory in the Western Hemisphere to the King of Castille.

- 8. Francisci de Victoria, De Indis et De ivre belli, relectiones. . . , ed. Ernest Nys (Washington, D. C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1917). Available online at: https://goo.gl/PsqWPj.

- 9. The word translated “Reconsideration” is the Latin Relectio.

- 10. That is, justification for taking the Indian lands.

- 11. We reproduce here a few pages of Bartolomé de Las Casas’ (1484–1566) account of the conquest of Hispaniola, from a modernized version of an early English translation of the work by an individual known only as M.M.S., retitled The Spanish Colonie (London: 1583); available online: https://goo.gl/H2YDtk. Las Casas participated in the conquest he recounts; he was also in Cuba during the conquest of that island. He eventually became a Dominican friar and worked for the rest of his life to protect the indigenous people of the Americas.

- 12. Of Hispaniola, present day Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.