No study questions

No related resources

Introduction

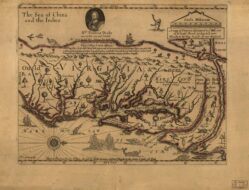

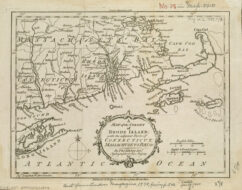

How to treat the indigenous people became an issue as soon as the Spanish arrived in the Western Hemisphere. In a letter written soon after his first voyage, Christopher Columbus explained how he dealt with the natives and revealed his and Spain’s religious motive for exploring what he conceived to be, in explicitly religious terms (see Christopher Columbus to Doña Juana de Torres, 1500) a New World. In addition to the converts to Catholicism that Columbus mentions, the Spanish sought gold. What means were allowable in pursuit of these ends? By what authority did the Spanish make claims on the native people and their land? The Requerimiento provided the official answer to these questions.

Whatever Spanish justifications, the Spanish conquistadores or conquerors proved brutal and rapacious as the conquest continued. The authorities in Madrid did not approve. For example, laws regulating conduct in the conquest were promulgated in 1513 and 1542 (the latter partially repealed in 1545 because of opposition). They relieved Christopher Columbus of command over land he had discovered in part because of his brutality toward both Spanish settlers and the indigenous people. Columbus complained of the injustice of his removal (see Christopher Columbus to Doña Juana de Torres, 1500), by emphasizing that the New World was not like Spain but was an uncivilized lawless territory. Francisco de Vitoria, on the contrary, (see De Indis) sought to mitigate the harshness of the conquest by arguing that law – civil, natural and divine – should prevail everywhere. He argued for limits on what could legitimately be done to the indigenous people. In doing so, he helped develop just war theory. Despite de Vitoria’s arguments, distance from Madrid, limited means of communication, and the need for colonial wealth reduced the ability and willingness of Spain’s monarchs to control what was done in their name thousands of miles away from their palaces. Bartolomé de las Casas (A Short Description of the Destruction of the Indies, 1542) describes the consequences of the Spanish conquest.

Source: Francisci de Victoria, De Indis et De ivre belli, relectiones. . . , ed. Ernest Nys (Washington, D. C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1917). Available online at: https://goo.gl/PsqWPj.

The First Reconsideration1 of the Reverend Father, Brother Franciscus De Victoria, on the Indians Lately Discovered.

First Section . . .

. . .

Fourth, . . . I ask first whether the aborigines in question were true owners in both private and public law before the arrival of the Spaniards; that is, whether they were true owners of private property and possessions and also whether there were among them any who were the true princes and overlords of others. . . .

. . . [I]f the aborigines had not dominion, it would seem that no other cause is assignable therefor except that they were sinners or were unbelievers or were witless or irrational. . . .

[Appealing to various authorities, de Vitoria argues that the aborigines cannot be deprived of their property because they are sinners.]

. . .

- . . . The Indian aborigines are not barred on this ground [lack of reason] from the exercise of true dominion. This is proved from the fact that the true state of the case is that they are not of unsound mind, but have, according to their kind, the use of reason. This is clear, because there is a certain method in their affairs, for they have polities which are orderly arranged and they have definite marriage and magistrates, overlords, laws, and workshops, and a system of exchange, all of which call for the use of reason; they also have a kind of religion. Further, they make no error in matters which are self-evident to others; this is witness to their use of reason. Also, God and nature are not wanting in the supply of what is necessary in great measure for the race. Now, the most conspicuous feature of man is reason, and power is useless which is not reducible to action. Also, it is through no fault of theirs that these aborigines have for many centuries been outside the pale of salvation, in that they have been born in sin and void of baptism and the use of reason whereby to seek out the things needful for salvation. Accordingly I for the most part attribute their seeming so unintelligent and stupid to a bad and barbarous upbringing, for even among ourselves we find many peasants who differ little from brutes.

- The upshot of all the preceding is, then, that the aborigines undoubtedly had true dominion in both public and private matters, just like Christians, and that neither their princes nor private persons could be despoiled of their property on the ground of their not being true owners. It would be harsh to deny to those, who have never done any wrong, what we grant to Saracens and Jews, who are the persistent enemies of Christianity. We do not deny that these latter peoples are true owners of their property, if they have not seized lands elsewhere belonging to Christians.

It remains to reply to the argument . . . that the aborigines in question seem to be slaves by nature because of their incapability of self-government. My answer to this is that Aristotle certainly did not mean to say that such as are not over-strong mentally are by nature subject to another’s power and incapable of dominion alike over themselves and other things; for this is civil and legal slavery, wherein none are slaves by nature. Nor does the Philosopher mean that, if any by nature are of weak mind, it is permissible to seize their patrimony and enslave them and put them up for sale; but what he means is that by defect of their nature they need to be ruled and governed by others and that it is good for them to be subject to others, just as sons need to be subject to their parents until of full age, and a wife to her husband. . . .

Second Section

It being premised, then, that the Indian aborigines are or were true owners, it remains to inquire by what title the Spaniards could have come into possession of them and their country. . . .

- Sixth proposition: Although the Christian faith may have been announced to the Indians with adequate demonstration and they have refused to receive it, yet this is not a reason which justifies making war on them and depriving them of their property. This conclusion is definitely stated by St. Thomas (Secunda Secundae, qu. 10, art. 8), where he says that unbelievers who have never received the faith, like Gentiles and Jews, are in no wise to be compelled to do so. This is the received conclusion of the doctors alike in the canon law and the civil law. The proof lies in the fact that belief is an operation of the will. Now, fear detracts greatly from the voluntary (Ethics, bk. 3), and it is a sacrilege to approach under the influence of servile fear as far as the mysteries and sacraments of Christ. . . .

Our proposition receives further proof from the use and custom of the Church. For never have Christian Emperors, who had as advisors the most holy and wise Pontiffs, made war on unbelievers for their refusal to accept the Christian religion. Further, war is no argument for the truth of the Christian faith. Therefore the Indians cannot be induced by war to believe, but rather to feign belief and reception of the Christian faith, which is monstrous and a sacrilege. . . .

Another, and a fifth title2 is seriously put forward, namely, the sins of these Indian aborigines. For it is alleged that, though their unbelief or their rejection of the Christian faith is not a good reason for making war on them, yet they may be attacked for other mortal sins which (so it is said) they have in numbers, and those very heinous. . . .

- I, however, assert the following proposition: Christian princes cannot, even by the authorization of the Pope, restrain the Indians from sins against the law of nature or punish them because of those sins. My first proof is that the writers in question build on a false hypothesis, namely, that the Pope has Jurisdiction over the Indian aborigines, as said above. . . .

Further, the Pope cannot make war on Christians on the ground of their being fornicators or thieves or, indeed, because they are sodomites; nor can he on that ground confiscate their land and give it to other princes; were that so, there would be daily changes of kingdoms, seeing that there are many sinners in every realm. And this is confirmed by the consideration that these sins are more heinous in Christians, who are aware that they are sins, than in barbarians, who have not that knowledge. Further, it would be a strange thing that the Pope, who cannot make laws for unbelievers, can yet sit in judgment and visit punishment upon them.

A further and convincing proof is the following: The aborigines in question are either bound to submit to the punishment awarded to the sins in question or they are not. If they are not bound, then the Pope cannot award such punishment. If they are bound, then they are bound to recognize the Pope as lord and lawgiver. Therefore, if they refuse such recognition, this in itself furnishes a ground for making war on them, which, however, the writers in question deny, as said above. And it would indeed be strange that the barbarians could with impunity deny the authority and jurisdiction of the Pope, and yet that they should be bound to submit to his award. Further, they who are not Christians cannot be subjected to the judgment of the Pope, for the Pope has no other right to condemn or punish them than as vicar of Christ. But, the writers in question admit – both Innocent and Augustinus of Ancona, and the Archbishop and Sylvester, too – that they cannot be punished because they do not receive Christ. Therefore [they cannot be punished] because they do not receive the judgment of the Pope, for the latter presupposes the former.

The insufficiency alike of this present title and of the preceding one, is shown by the fact that, even in the Old Testament, where much was done by force of arms, the people of Israel never seized the land of unbelievers either because they were unbelievers or idolaters or because they were guilty of other sins against nature (and there were people guilty of many such sins, in that they were idolaters and committed many other sins against nature, as by sacrificing their sons and daughters to devils), but because of either a special gift from God or because their enemies had hindered their passage or had attacked them. . . .

. . . There remains another, a sixth title, which is put forward, namely, by voluntary choice. For on the arrival of the Spaniards we find them declaring to the aborigines how the King of Spain has sent them for their good and admonishing them to receive and accept him as lord and king; and the aborigines replied that they were content to do so. . . . I, however, assert the proposition that this title, too, is insufficient. This appears, in the first place, because fear and ignorance, which vitiate every choice, ought to be absent. But they were markedly operative in the cases of choice and acceptance under consideration, for the Indians did not know what they were doing; nay, they may not have understood what the Spaniards were seeking. Further, we find the Spaniards seeking it in armed array from an unwarlike and timid crowd. Further, inasmuch as the aborigines, as said above, had real lords and princes, the populace could not procure new lords without other reasonable cause, this being to the hurt of their former lords. Further, on the other hand, these lords themselves could not appoint a new prince without the assent of the populace. Seeing, then, that in such cases of choice and acceptance as these there are not present all the requisite elements of a valid choice, the title under review is utterly inadequate and unlawful for seizing and retaining the provinces in question.

There is a seventh title which can be set up, namely, by special grant from God. For some (I know not who) assert that the Lord by His especial judgment condemned all the barbarians in question to perdition because of their abominations and delivered them into the hands of the Spaniards, just as of old He delivered the Canaanites into the hands of the Jews. I am loath to dispute hereon at any length, for it would be hazardous to give credence to one who asserts a prophecy against the common law and against the rules of Scripture, unless his doctrine were confirmed by miracles. Now, no such are adduced by prophets of this type. Further, even assuming that it is true that the Lord had determined to bring the barbarians to perdition, it would not follow, therefore, that he who wrought their ruin would be blameless, any more than the Kings of Babylon who led their army against Jerusalem and carried away the children of Israel into captivity were blameless, although in actual fact all of this was by the especial providence of God, as had often been foretold to them. . . .

Let this suffice about false and inadequate titles to seize the lands of the Indians. . . .

Third Section . . .

. . .

- Fifth proposition: If the Indian natives wish to prevent the Spaniards from enjoying any of their above-named rights under the law of nations, for instance, trade or other above-named matter, the Spaniards ought in the first place to use reason and persuasion in order to remove scandal and ought to show in all possible methods that they do not come to the hurt of the natives, but wish to sojourn as peaceful guests and to travel without doing the natives any harm; – and they ought to show this not only by word, but also by reason, according to the saying, “It behoveth the prudent to make trial of everything by words first.” But if, after this recourse to reason, the barbarians decline to agree and propose to use force, the Spaniards can defend themselves and do all that consists with their own safety, it being lawful to repel force by force. . . .

It is, however, to be noted that the natives being timid by nature and in other respects dull and stupid, however much the Spaniards may desire to remove their fears and reassure them with regard to peaceful dealings with each other, they may very excusably continue afraid at the sight of men strange in garb and armed and much more powerful than themselves. And therefore, if, under the influence of these fears, they unite their efforts to drive out the Spaniards or even to slay them, the Spaniards might, indeed, defend themselves but within the limits of permissible self-protection, and it would not be right for them to enforce against the natives any of the other rights of war (as, for instance, after winning the victory and obtaining safety, to slay them or despoil them of their goods or seize their cities), because on our hypothesis the natives are innocent and are justified in feeling afraid. Accordingly, the Spaniards ought to defend themselves, but so far as possible with the least damage to the natives, the war being a purely defensive one.

There is no inconsistency, indeed, in holding the war to be a just war on both sides, seeing that on one side there is right and on the other side there is invincible ignorance. For instance, just as the French hold the province of Burgundy with demonstrable ignorance, in the belief that it belongs to them, while our Emperor’s right to it is certain, and he may make war to regain it, just as the French may defend it, so it may also befall in the case of the Indians – a point deserving careful attention. For the rights of war which may be invoked against men who are really guilty and lawless differ from those which may be invoked against the innocent and ignorant, just as the scandal of the Pharisees is to be avoided in a different way from that of the self-distrustful and weak.

- Sixth proposition: If after recourse to all other measures, the Spaniards are unable to obtain safety as regards the native Indians, save by seizing their cities and reducing them to subjection, they may lawfully proceed to these extremities. . . .

- Seventh proposition: If, after the Spaniards have used all diligence, both in deed and in word, to show that nothing will come from them to interfere with the peace and well-being of the aborigines, the latter nevertheless persist in their hostility and do their best to destroy the Spaniards, then they can make war on the Indians, no longer as on innocent folk, but as against forsworn enemies, and may enforce against them all the rights of war, despoiling them of their goods, reducing them to captivity, deposing their former lords and setting up new ones, yet withal with observance of proportion as regards the nature of the circumstances and of the wrongs done to them. . . .

. . .

- There is another title which can indeed not be asserted, but brought up for discussion, and some think it a lawful one. I dare not affirm it at all, nor do I entirely condemn it. It is this: Although the aborigines in question are (as has been said above) not wholly unintelligent, yet they are little short of that condition, and so are unfit to found or administer a lawful State up to the standard required by human and civil claims. . . . It might, therefore, be maintained that in their own interests the sovereigns of Spain might undertake the administration of their country, providing them with prefects and governors for their towns, and might even give them new lords, so long as this was clearly for their benefit. I say there would be some force in this contention. . . . The same principle seems to apply here to them as to people of defective intelligence; and indeed they are no whit or little better than such so far as self-government is concerned, or even than the wild beasts, for their food is not more pleasant and hardly better than that of beasts. Therefore their governance should in the same way be entrusted to people of intelligence. . . . And surely this might be founded on the precept of charity, they being our neighbors and we being bound to look after their welfare. Let this, however, as I have already said, be put forward without dogmatism and subject also to the limitation that any such interposition be for the welfare and in the interests of the Indians and not merely for the profit of the Spaniards. For this is the respect in which all the danger to soul and salvation lies. And herein some help might be gotten from the consideration, referred to above, that some are by nature slaves, for all the barbarians in question are of that type and so they may in part be governed as slaves are.

The Second Reconsideration of the Reverend Father, Brother Franciscus De Vitoria, On The Indians, or On The Law of War Made by the Spaniards on the Barbarians.

Inasmuch as the seizure and occupation of those lands of the barbarians whom we style Indians can best, it seems, be defended under the law of war, I propose to supplement the foregoing discussion of the titles, some just and some unjust, which the Spaniards may allege for their hold on the lands in question, by a short discussion of the law of war, so as to give more completeness to that [first] reconsideration [relectio]. . . .

. . .

- Fourth proposition: There is a single and only just cause for commencing a war, namely, a wrong received. . . .

- Fifth proposition: Not every kind and degree of wrong can suffice for commencing a war. . . . As, then, the evils inflicted in war are all of a severe and atrocious character, such as slaughter and fire and devastation, it is not lawful for slight wrongs to pursue the authors of the wrongs with war, seeing that the degree of the punishment ought to correspond to the measure of the offence (Deuteronomy, ch. 25). . . .

. . .

- . . . Great attention, however, must be paid to the point already taken, namely, the obligation to see that greater evils do not arise out of the war than the war would avert. . . . [I]t is never right to slay the guiltless, even as an indirect and unintended result, except when there is no other means of carrying on the operations of a just war, according to the passage (St. Matthew, ch. 13) “Let the tares grow, lest while ye gather up the tares ye root up also the wheat with them.” . . .

. . .

- Assuming the unlawfulness of the slaughter of children and other innocent parties, is it permissible, at any rate, to carry them off into captivity and slavery? This can be cleared up in a single proposition, namely: It is in precisely the same way permissible to carry the innocent off into captivity as to despoil them, liberty and slavery being included among the good things of Fortune. And so when a war is at that pass that the indiscriminate spoliation of all enemy-subjects alike and the seizure of all their goods are justifiable, then it is also justifiable to carry all enemy-subjects off into captivity, whether they be guilty or guiltless. And inasmuch as war with pagans is of this type, seeing that it is perpetual and that they can never make amends for the wrongs and damages they have wrought, it is indubitably lawful to carry off both the children and the women of the Saracens into captivity and slavery. But inasmuch as, by the law of nations, it is a received rule of Christendom that Christians do not become slaves in right of war, this enslaving is not lawful in a war between Christians; but if it is necessary having regard to the end and aim of war, it would be lawful to carry away even innocent captives, such as children and women, not indeed into slavery, but so that we may receive a money-ransom for them. This, however, must not be pushed beyond what the necessity of the war may demand and what the custom of lawful belligerents has allowed.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.