Abraham Lincoln

In 1854, Abraham Lincoln said of Thomas Jefferson that he “was, is, and perhaps will continue to be our most distinguished politician.” We may now say this of Lincoln. And just as Lincoln meant that one must understand Jefferson’s politics and principles—his deeds and his words—to understand the United States, so must we now say that to understand the United States we must understand Lincoln’s deeds and words. We offer this volume as an aid in the effort to understand Lincoln and, through him, what remains the world’s most important experiment in self-government.

This collection offers twenty-six of Lincoln’s most important speeches and writings, each accompanied by an introduction that provides historical context. The most important context was, of course, the struggle over slavery.

The Struggle over Slavery

Slavery—and who bore the responsibility for its existence in America—was discussed when the Continental Congress reviewed Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence. Later, those drafting the Constitution included three provisions concerning slavery, without ever mentioning the peculiar institution by name. (At the convention, James Madison remarked that it would be “wrong to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.”) First, the framers allowed “all other persons” besides “free persons” and “Indians not taxed” to be counted as three-fifths of a free person for purposes of taxation and representation (Art. I, sec. 2). This was a compromise among the delegates who wanted to count enslaved people when determining a state’s population (and thus the number of representatives in the House of Representatives and Electoral College votes) and those who did not. Second, the Constitution provided that the importation of “persons” by a state could not be prohibited for twenty years after its adoption—until 1808. This was a compromise between those who wanted to ban the importation of slaves immediately and those who wished there to be no prohibition at all on the slave trade (Art. I, sec. 9). In addition to these two compromises, the Constitution also contained a provision that “no person held to service” in one state would be discharged from that service in another. Rather, the Constitution made it an obligation to return such persons to those to whom their labor was due (Art. IV, sec. 2). This provision became known as the fugitive slave clause. To implement it, Congress passed the first fugitive slave law in 1793.

In 1807, in what Lincoln called “apparent hot haste,” Congress passed a law prohibiting the importation of slaves beginning on the first day of January 1808. Four years before the passage of this law, the United States had acquired the Louisiana territory. After Louisiana was admitted to statehood in 1812, the next territory from this acquisition to apply for admission as a state was Missouri, in 1819, under a constitution that permitted slavery. At the time, there were eleven free and eleven slave states. Missouri was not admitted as a slave state until Maine applied for statehood and was admitted as a free state. As part of this compromise, Congress included in the Missouri statehood enabling act the provision that in the remainder of the Louisiana territory slavery would forever be prohibited north of latitude 36º 30´ N. (Lincoln recounted the history of the struggle over slavery from the founding through the sectional conflict in Document 4, his speech on the repeal of the Missouri Compromise.)

In 1836, Texas separated from Mexico through a revolution and declared itself a separate republic, claiming territory to the west and north encompassing parts of the current U.S. states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico. When Texas joined the Union in 1845, war with Mexico followed (Mexico considered Texas still part of its territory). Early in the war, when President James Polk asked for an appropriation for peace negotiations, Representative David Wilmot (D-PA) proposed an amendment to the appropriations bill stating that slavery would not be permitted in any territory gained from Mexico in the peace negotiations. The bill passed the House but not the Senate. Subsequent versions of Wilmot’s amendment met the same fate. The treaty that eventually ended the war, which had to be ratified only by the Senate, contained no prohibition of slavery. The contest between free state and slavery advocates over this territory and what remained of the Louisiana territory was the final phase of the sectional conflict leading to the Civil War.

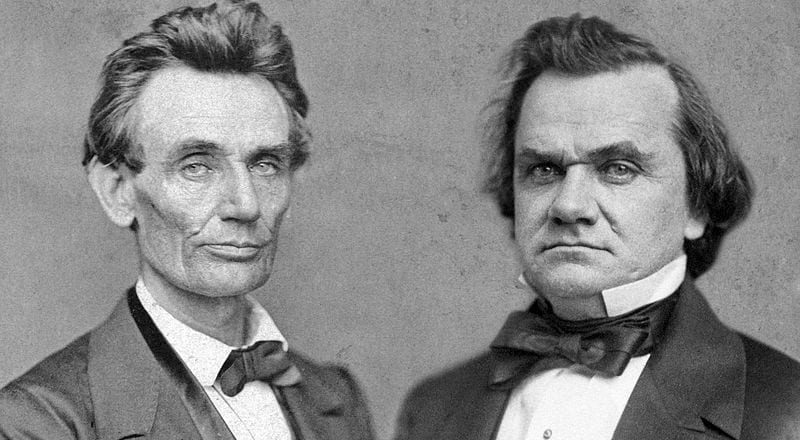

Following the Mexican War, California applied for admission as a free state. At that point, the number of free and slave states was equal (fifteen each). California’s application for admission thus precipitated a crisis, just as Missouri’s had thirty years before. The crisis was resolved by the Compromise of 1850, which consisted of five separate pieces of legislation. Stephen A. Douglas (1813–1861), a Democratic senator from Illinois, was responsible for getting the legislation passed. The bills admitted California as a free state; set the boundary between Texas and New Mexico and compensated Texas for giving up land claims beyond that boundary; set up territorial governments for Utah and New Mexico, with the provision that the territories could eventually enter the Union as either free or slave states; abolished the slave trade (but not slavery) in the District of Columbia; and strengthened the federal fugitive slave law.

When it came time to organize territories north of Texas that were part of the Louisiana purchase, Senator Douglas again took the lead. In 1854 he proposed the Kansas-Nebraska bill, accepting an amendment that rescinded the Missouri Compromise line of 36º 30´, which was supposed to have been established forever, and leaving the decision regarding slavery to each territory’s inhabitants (see Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise). Douglas called such decision making “popular sovereignty”—the people should decide without the interference of the federal government—declaring it the simplest and fairest way of resolving the controversy over slavery. The bill’s immediate practical result, however, was to foment civil violence. Everyone understood that once slavery became established in a territory, it would receive the protection of territorial law. Thus protected, slavery would grow and become ever harder to abolish. Free state and slave state advocates in and beyond Kansas and Nebraska fought to gain the advantage and determine whether this peculiar form of property would be allowed. As one scholar put it, “the Kansas-Nebraska Act legislated civil war on the plains of Kansas.”

The civil war in “Bleeding Kansas” magnified the sectional conflict and pointed toward the greater civil war that would begin six years later. This conflict became even more likely in 1857 as a result of the Dred Scott decision (see Reply to the Dred Scott Decision), in which the Supreme Court held (7–2) that persons of African descent were not citizens and had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The Court went further and declared that Congress could not prohibit slavery in the territories because the right to hold property in slaves was “distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution.” If the right to hold slaves was in the Constitution, however, did that not imply that Southerners had the right to take their property into any state? The Dred Scott opinion suggested at least the possibility that a future Court ruling might declare slavery to be the national norm, permissible even in those states that had decades earlier declared it illegal.

Lincoln returned to politics during the controversy over the KansasNebraska act, recognizing the danger to self-government and human liberty should Douglas’ understanding of “popular sovereignty” prevail (see Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise). If the people in a territory chose to admit slavery—ignoring the Declaration’s assertion that all men are created equal—then they would undermine the principle on which their own freedom was based. Among the people, popular sovereignty was the strongest and the most obvious and easily grasped principle of the Republic. Unlike Douglas, Lincoln through his words and deeds had to show the people that the only thing more important than that principle was its ultimate cause, human equality. More difficult, he had to show the people that preserving their liberty meant restricting their freedom: there were some things that the people could not rightly choose to do.

The Civil War and Reconstruction

Lincoln won the presidency in 1860 on a platform of preventing the spread of slavery beyond the states where it already existed, and affirming the Declaration’s claim that all men were created equal. Lincoln defeated the other three presidential candidates with a plurality of the vote and amassed more Electoral College votes than his three opponents combined. His election precipitated the secession—as they called it—of seven states, ultimately joined by four others. Lincoln denied that secession was legal or constitutional. The states that claimed to have left the Union were thus in rebellion (see Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address).

What Lincoln could accomplish to end the rebellion and save the Union, which he considered his principal duty as president (see Letter To Horace Greeley), depended on four considerations, each requiring his careful attention: northern support for the war; the opinions of those in the border states (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri); the actions toward the rebellious states of foreign powers, especially Great Britain; and the success of Union military forces against the rebel armies (see Message to Congress in Special Session, Annual Message to Congress 1861, and Annual Message to Congress, 1862). In the North and the border states, opinions on slavery and the Union varied. Some were so strongly in favor of slavery that they were willing to let the Union go to preserve it; others were so strongly opposed to slavery that they were willing to dissolve the Union to rid themselves of it. Still others were unwilling to surrender the Union and were willing to compromise with slaveholders to keep it together. Pervading public opinion, even among antislavery stalwarts, was an unforgiving prejudice against African Americans, evident in the offensive terms that appear in some of these documents (e.g., Lincoln-Douglas Debates). Lincoln, however, understood that preserving the Union ultimately meant ending slavery. Slavery was incompatible with the Declaration’s claim of equality, and the Constitution and the Union existed to serve the Declaration (See Fragment on the Constitution and Union). In everything he said and did to preserve the Union and end slavery, Lincoln took into account the opinions and prejudices of the varied audiences he addressed.

As for the success of Union military forces, for the first years of the war they had little. The tide turned, however, when Lincoln put in command generals prepared to seek decisive victory over Confederate forces. The turning point came first at Vicksburg and Gettysburg in the summer of 1863, and then in the all-important Virginia theater of the war after Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885) took command (1864) of all Union forces.

The prospect of Union victory raised the question of how to return the rebellious states to the Union. Historically, defeated rebels had received harsh treatment. “Radical” Republicans favored this approach. Lincoln sought a more moderate course, making acceptance of the Thirteenth Amendment (1865) abolishing slavery a requirement for regaining their civil status, and seeking some way to provide for the formerly enslaved. Early in his second administration—just as he was about to embark on the arduous task of reconstruction—Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865 (See Last Public Address).

Meaning of the Declaration of Independence and Equality

- Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise

- Speech at Chicago, Illinois

- Lincoln-Douglas Debates

- Address in Independence Hall

- Gettysburg Address

The Relationship between the Declaration and the Constitution

- Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise

- Reply to the Dred Scott Decision

- Fragment on the Constitution and Union

Popular Sovereignty

The Rule of Law

- “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions”

- Reply to the Dred Scott Decision

- Message to Congress in Special Session

- To Erastus Corning et al.

- Response to a Serenade

Religion and Politics

Civil War Policies

- First Inaugural Address

- Message to Congress in Special Session

- Annual Message to Congress, 1861

- Annual Message to Congress, 1862

- Lincoln to James C. Conkling

Emancipation

Colonization

- Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise

- Address on Colonization to a Committee of Colored Men

- Annual Message to Congress

Labor and Capital

The Republican Party

Reconstruction

For each of the Documents in this collection, we suggest below in section 1 questions relevant for that document alone and in Section 2 questions that require comparison with other documents.

Abraham Lincoln, “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions” (Lyceum Address), January 27, 1838

- What dangers did Lincoln foresee for the perpetuation of America’s political institutions? How were they related? Did these dangers arise only because of our institutions or were they always present in political life? What circumstances contributed to them? What did Lincoln mean at the end of his speech when he appealed to “reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason”?

- Do you see any of the problems Lincoln considered in the Lyceum Address in his First Inaugural Address? In his comments at Alton during the Lincoln-Douglas debates? Was Lincoln consistent in his argument about obeying the law in the Lyceum Address and in his speech about the Dred Scott decision?

Temperance Address, February 22, 1842

- How did Lincoln connect slavery and drunkenness in the speech? Do you think that Lincoln thought that the “Reign of Reason” would ever come? The temperance movement was meant to free people from drink, but did temperance itself pose problems for freedom? What political problem did Lincoln see associated with the temperance movement? Did he see a problem with religion’s role in a political order based on human equality? Did he see problems with only a certain kind of religion? What characteristics of religion make it a problem for a government based on human equality?

- Are Lincoln’s views of God’s relation to humans the same in the Temperance Address and the Second Inaugural? Is there a similarity in his view of Southerners in the Second Inaugural and his view of drunkards in the Temperance Address?

Eulogy on Henry Clay, July 16, 1852

- Why did Lincoln consider Clay his model statesman? What qualities in Clay did Lincoln admire?

- Consider the arguments Lincoln made in the Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise Peoria, Illinois, The Lincoln-Douglas Debates, his First Inaugural Address, and his Last Public Address. To what extent did these arguments reflect what Lincoln learned from the speeches and career of Henry Clay?

Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise, October 16, 1854

- Explain Lincoln’s distinction between the existing institution of slavery and its extension. What historical precedents did Lincoln appeal to in support of the federal government’s restriction of slavery? What did Lincoln propose to do about slavery? What limits did he recognize in doing so? How did popular sovereignty’s declared indifference to slavery lead to “an open war” with “the fundamental principles of civil liberty” in the Declaration of Independence? Identify Lincoln’s references to the Bible in the speech. How were they used? What was the “ancient faith” and how did it differ from the “new faith” of popular sovereignty? Explain Lincoln’s understanding of the Constitution and slavery. What was his view of the Founders? What evidence did Lincoln provide in support of the view that Southerners themselves recognized the humanity of the slave? What did Lincoln mean when he described slavery as a “necessary evil”? What is the relationship between the doctrine of self-government and consent? What did Lincoln mean when he said, “Stand with anybody that stands right”? How is the principle of slavery comparable to the divine right of kings?

- Compare and contrast what Lincoln said about colonization in the Missouri Compromise speech in Peoria with what he said to the delegation of African Americans in August 1862. How did Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address acknowledge the distinction made in the Peoria speech between the existing institution of slavery and its extension? To what extent was Lincoln’s view of black freedom in his Last Public Address consistent with what he said about race and equality in the Peoria speech? Is Lincoln’s position on the question of black suffrage and racial equality different in the Peoria speech and later speeches, such as his Last Public Address? If so, what do you think accounts for the change?

Reply to the Dred Scott Decision, June 26, 1857

- On what grounds did Lincoln hold that the Court’s decision in the Dred Scott case was not settled? How did Lincoln respond to Chief Justice Roger Taney’s interpretations of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution? In opposition to Douglas and Taney, how did Lincoln understand and explain the equality principle of the Declaration and its application to African Americans? What did he mean when he said that the Declaration promised Americans something better than the condition of British subjects? Why did Lincoln discuss the amalgamation of the races?

- Do Lincoln’s comments about his opposition to the Dred Scott decision contradict what he said in the Lyceum Speech about the importance of obeying the law? Did Lincoln see the same implications in the Dred Scott decision in this speech and in his House Divided Speech? If there are differences, what might account for them? Compare Lincoln’s comments in this speech about the Declaration with those he made in his Address in Independence Hall. Are there any differences? How would you explain Lincoln’s view of the promise of the Declaration?

House Divided Speech, June 16, 1858

- What did Lincoln mean when he said, “A house divided against itself cannot stand”? How did he support that statement? It is sometimes argued that the House Divided Speech helped to bring on the Civil War; what justification could be given for Lincoln’s making such an inflammatory speech?

- Does Lincoln’s argument in “House Divided” contradict what he said about holding the Union together in his First Inaugural Address or his conciliatory approach in the Temperance Address or the Second Inaugural Address? How did Douglas use the House Divided Speech against Lincoln during their debates? How did Lincoln respond?

Speech at Chicago, Illinois, July 10, 1858

- What accusations did Douglas make against Lincoln’s House Divided Speech? How did Lincoln rebut these charges? How did Lincoln exploit the split in the Democratic Party between Buchanan and Douglas over the Lecompton Constitution? What is the difference, if any, between popular sovereignty and squatter sovereignty? According to Lincoln, how did the Dred Scott ruling contradict popular sovereignty? How did Lincoln attempt to reconcile his opposition to Dred Scott with his support for the rule of law and the Constitution? To what extent did Lincoln concede that “this government was made for white men” and how did he qualify this statement? Explain Lincoln’s metaphors of the Declaration as an “electric cord” and the principle of equality as “the father of all moral principle.”

- What arguments did Lincoln make in Chicago that he repeated in the debates with Douglas? Compare what Lincoln said about Dred Scott in Chicago with what he said in 1857. Did Lincoln contradict himself when he argued that the Declaration’s claim that all men are equal was like the command to be perfect like God? Compare Lincoln’s appeal to Matthew 5:48 in describing the aspiration to realize as much as possible the principles of the Declaration, even if falling short, and what he said in his Dred Scott speech about the Declaration as a “standard maxim” of freedom.

Fragment on Slavery and Democracy, 1858

- What underlying principle makes slavery incompatible with democracy? What is wrong with wanting to be a master and why would Lincoln not want to be one? How does this fragment presume the Golden Rule, “so in everything, do to others what you would have them do to you” (Matthew 7:12)? Can you provide historical evidence of democracy and slavery coexisting?

- Did Lincoln’s efforts to promote emigration of African Americans contradict what he said here about democracy? Did democracy require social equality among blacks and whites (compare Speech at Chicago, Illinois and Lincoln-Douglas Debates)? Did it require that African Americans be given the vote (See Last Public Address)?

Lincoln-Douglas Debates, August–October 1858

- How do Lincoln’s and Douglas’ views of the Declaration differ? Who should or should not be included in the proposition that “all men are created equal”? How did Douglas attempt to stigmatize Lincoln and the Republicans as “the Abolition Party”? Why might this strategy have been effective in Illinois? What was Douglas’ critique of Lincoln’s House Divided Speech and how did Lincoln reply to this attack? What were the “bonds of Union” described by Lincoln? What evidence did Lincoln provide that his views were consistent with those of the Founding Fathers? How, in Lincoln’s view, did popular sovereignty lead to a change in the public mind over slavery and “a new basis” that looked to slavery’s “perpetuity and nationalization”? What evidence did Lincoln provide to support his allegation that there was a conspiracy to make slavery national? How did Douglas and Lincoln approach the Dred Scott decision? How did Douglas appeal to racial prejudice against Lincoln? Did Lincoln’s remarks at Charleston make him a white supremacist? What other factors might account for this statement?

- To what extent did Lincoln’s statement at Peoria that “a universal feeling, whether well or ill-founded, cannot be safely disregarded” account for what he said about race in the debate at Charleston? How did Lincoln attempt to reconcile his opposition to Dred Scott with his devotion to the rule of law (See the Lyceum Address) and with what he later said about the Court in his First Inaugural Address?

Address before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society, September 30, 1859

- What is the “mud sill” theory? What is the relationship between capital and labor according to the mud sill theory? What arguments did Lincoln make against this theory? How, according to Lincoln, was labor prior to capital? Do you think in providing the example of the prudent penniless beginner that Lincoln had himself in mind? To what extent did Lincoln’s views on free labor apply to African Americans? What were Lincoln’s views of human motivation, perseverance, and hard work? Did Lincoln overestimate success in terms of individual responsibility rather than social circumstances? How did Lincoln’s defense of free labor appeal to the authority of “the Author of man”? What role did discovery and invention play in this speech? How were education, labor, liberty, and happiness related according to Lincoln

- Lincoln included passages from this speech in his Second Annual Message to Congress, December 1, 1862. How were Lincoln’s thoughts on labor and the right to improve one’s situation related to what he said about black freedom in the letter to Conkling? How did Lincoln discuss the principle of consent in this speech? How does it compare to what he said in the Peoria speech? How is the view of labor in this speech reflected in the final Emancipation Proclamation’s enjoinder to the freedmen “to labor faithfully for reasonable wages”

Address at Cooper Union, February 27, 1860

- What was Lincoln’s purpose in giving this speech? Did he make his case that the Founders intended the federal government to have authority over slavery in the territories? Is his defense of the Republican Party convincing?

- Lincoln was speaking to an audience comprised largely of Republicans. Why did he take such a lawyerly tone in this speech? Compare his remarks here to other speeches with different audiences, such as the one he gave at Peoria, during his debates with Douglas, or in others in this volume. Did he change what he said depending on his audience, or were the changes mostly in tone and emphasis rather than in substance?

Fragment on the Constitution and Union, January 1861

- What did Lincoln mean when he spoke of a “philosophical cause”? What was that cause? How was it the case that the cause “clears the path for all—gives hope to all—and by consequence, enterprise, and industry to all”?

- Does Lincoln’s subordination of the Constitution in this fragment contradict what he said about the importance of the rule of law in the Lyceum Speech? What is the connection between the equality that Lincoln extolled in this fragment and in other speeches in this collection and the law?

Address in Independence Hall, February 22, 1860

- What was the context of this speech? What was happening in the country and in Lincoln’s life? How do Lincoln’s remarks reflect the historical significance of the date and place? How did the Declaration give “hope” to the world for all future time? What did Lincoln mean when he said that “in due time the weight would be lifted from the shoulders of all men”? Explain what Lincoln meant when he said that the country must be saved upon “that basis.” Why did Lincoln mention assassination? With what assurance and warning did Lincoln conclude his speech? What evidence supports the view that Lincoln’s remarks were impromptu?

- Compare Lincoln’s view of the Union in this speech to what he said about the “apple of gold and picture of silver” in Document 12. Is there a difference? In dealing with the threat of impending Civil War, how does this speech compare to what Lincoln said in the First Inaugural? Is one more conciliatory than the other? What might account for any differences? Compare what Lincoln said about American exceptionalism as providing “hope” to the world in this speech with what he said in his July 4, 1861, Message to Congress in Special Session and his Annual Message to Congress in 1862.

First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861

- What was Lincoln willing to do in order to pacify the South? What was he not willing to do? What arguments did Lincoln give in defense of the perpetuity of the Union? How did Lincoln differentiate “secession” and “revolution”? Why was that significant given the circumstances? What did Lincoln think constituted “the only substantial dispute” between the North and the South? Why did responsibility for initiating the Civil War rest squarely on the shoulders of the South, according to Lincoln’s argument at the end of the speech?

- How do Lincoln’s arguments against secession in the First Inaugural Address compare to those he made in the Message to the Special Session of Congress? Why was it important to Lincoln to make such arguments? How do they compare to the arguments he made in the Lyceum Address?

Message to Congress in Special Session, July 4, 1861

- Why did Lincoln go to such lengths to explain and defend his actions? What does that tell us about the political situation he faced? Do you think Lincoln succeeded in justifying his suspension of habeas corpus?

- How do Lincoln’s arguments against secession in the message to the special session compare to those he made in the First Inaugural Address? Why was it important to Lincoln to make such arguments? How do they compare to the arguments he made in the Lyceum Address?

Annual Message to Congress, December 3, 1861

- Why was Lincoln cautious about setting up courts under military power in areas regained by Union forces so that private debts could be recovered from people in these areas? Why did Lincoln argue in this speech for the superiority of labor over capital? Lincoln said that he kept the integrity of the Union in mind as the primary object of the war. What did he mean by “integrity of the Union”? In this connection, why did he say that he did not want efforts to suppress the rebellion to degenerate into “a violent and remorseless revolutionary struggle”? To avoid this, why did he want to emphasize “the more deliberate action of the legislature.”

- Compare what Lincoln said about the legislature in his First Annual Message with his remarks about Congress in his Last Public Address. Did Lincoln’s attitude toward the role of Congress change in the interim? Is there a change in tone between the first and second annual messages? If so, why might this be the case? Do they cover the same issues with regard to the war? Did Lincoln’s emphasis on the integrity of the Union change? Consider Horace Greeley.

Address on Colonization to a Committee of Colored Men, August 14, 1862

- What were the circumstances of this speech to the African American delegation? What was happening in the country in August 1862? Why did Lincoln propose colonization? Were Lincoln’s remarks those of a white supremacist? To what extent can this meeting be seen as a public relations effort on Lincoln’s part? To what extent might these remarks inflame hatred against blacks? What happened to colonization proposals by 1864?

- Compare and contrast Lincoln’s remarks on colonization in this speech with what he said about it at Peoria in 1854. Compare these remarks with Lincoln’s remarks at Charleston during the Lincoln-Douglas Debates in 1858. To what extent was Lincoln accommodating public prejudice in these speeches? Should he have accommodated public opinion?

To Horace Greeley, August 22, 1862

- What three scenarios to save the Union did Lincoln outline in this letter? Which of these scenarios did Lincoln actually pursue when he issued the Emancipation Proclamation? Which were the border slave states, and to which party did they belong? Why were they important to the success of the Union cause? Did Lincoln’s “paramount object” exclude ending slavery? Explain Lincoln’s distinction between his “personal wish” and his “official duty”?

- Is there a contradiction between Lincoln’s pledge not to touch the existing institution of slavery in his First Inaugural Address and his implicit suggestion in the letter to Greeley that he might do so? What circumstances might have changed between these two speeches? Compare and contrast the letter to Greeley with the Address on Colonization the same month. How might both of these documents be seen as part of a public relations campaign to support the coming Emancipation Proclamation? Is the letter to Greeley consistent with what Lincoln pledged at Independence Hall? How might the letter to Greeley be interpreted as Lincoln attempting to preserve both the apple of gold and the picture of silver (See Cooper Union Address)?

Preliminary and Final Emancipation Proclamations, September 22, 1862, January 1, 1863

- Why did Lincoln have to base emancipation on military necessity? In what ways do the two Proclamations differ? Why do those differences exist?

- Is there a contradiction between Lincoln’s pledge not to touch the existing institution of slavery in his First Inaugural Address and the two Proclamations? In issuing the Proclamations, did Lincoln contradict what he said in his letter to Horace Greeley? How had circumstances changed between the Inaugural Address and the Proclamations? Was Lincoln serving the same or different purposes in the two documents?

Annual Message to Congress, December 1, 1862

- Why did Lincoln introduce his discussion of the proposed emancipation amendment with a meditation on what a nation consists of? After having issued the Emancipation Proclamations, why did Lincoln think it necessary to propose an emancipation amendment? What arguments did Lincoln make to justify the amendment? What do you think he saw as the biggest obstacles to its passage? What were the dogmas that Lincoln said were no longer adequate?

- Do Lincoln’s arguments and plans for emancipation and colonization in the annual message differ from arguments he made in the Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise Peoria, Address on Colonization to a Committee of Colored Men, and the Preliminary and Final Emancipation Proclamations?

To Erastus Corning et al., June 12, 1863

- How did Lincoln summarize the arguments of his critics? Do you think Lincoln was right to criticize the patriotic motives of his critics? What fundamental freedoms, rights, and safeguards did Lincoln allegedly violate? How did Lincoln disagree with his critics over “the grounds of arrests”? What constitutional basis did Lincoln cite in support of his argument? How might Lincoln’s rhetorical antithesis between the “wily agitator” Vallandigham and “a simple-simple minded soldier boy” who is shot for desertion have resonated with the public at this time? On what basis did Lincoln concede that Vallandigham’s arrest might have been wrong? What then, according to Lincoln, was the rationale for Vallandigham’s arrest? How did Lincoln appeal to the precedent of Andrew Jackson

- Compare and contrast Lincoln’s rationale in defense of his extraordinary measures with what he said about the suspension of habeas corpus in his Message to Congress in Special Session. Why did Lincoln appeal to the example of President Jackson in this document and in his speech about the Dred Scott decision?

To James C. Conkling, August 26, 1863

- What are the “three conceivable” ways Lincoln outlined for ending the rebellion? Which way did Lincoln prefer? Why was there dissatisfaction with Lincoln’s policies? What, according to Lincoln, was the greatest source of this dissatisfaction? How did Lincoln defend freedom for African Americans in this speech? Notwithstanding their disagreement with his policies, how did he attempt to keep these opponents part of the war coalition to save the Union? Do you think his appeal is effective?

- Compare Lincoln’s views on black freedom in this speech with his remarks to the African American delegation on Colonization. Are Lincoln’s views on race consistent in these two speeches? Compare the tone of Lincoln’s Conkling letter to that of the Corning and Greeley letters. Do they differ? To what extent is Lincoln’s letter to Conkling consistent with his remark in his Second Annual Address to Congress, December 1, 1862, that “the dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. … As our case is new, so must think anew, and at anew”?

Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863

- “Four score and seven years ago” (87 years) dates the country to 1776. Why did Lincoln use that date rather than a date associated with the Constitution? The Declaration of Independence says that it is a self-evident truth that all men are created equal. At Gettysburg, Lincoln called it a proposition. What is the difference between a proposition and a self-evident truth? Why do you think Lincoln used the term “proposition”? What did Lincoln mean by the phrase “a new birth of freedom”

- Compare Lincoln’s argument in the Gettysburg Address with his fragment on the Constitution and Union. Does each document show the same understanding of the relationship between the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution? How would you explain Lincoln’s understanding of that relationship? If you consider what Lincoln said in his speech at Peoria about equality, do you think that he said something different in the Gettysburg Address?

Response to a Serenade, November 10, 1864

- What did Lincoln mean when he stated, “It has long been a grave question whether any government, not too strong for the liberties of its people, can be strong enough to maintain its own existence in great emergencies”? How did Lincoln frame the election as a test? What did Lincoln observe about the Union cause in his remarks? What did he say about human nature? In addition to the war itself, can you provide other examples of the “strife” Lincoln mentioned in the speech?

- How did Lincoln’s serenade response anticipate his plea for “malice toward none” in the Second Inaugural Address? Compare and contrast Lincoln’s remarks in this speech about balancing liberty and order with what he said in the July 4, 1861, Message to Congress in Special Session. Compare and contrast what Lincoln said about elections in this speech to what he said in his First Inaugural. Compare and contrast Lincoln’s praise of patriotism in this speech with what he said in his Eulogy on Henry Clay.

Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865

- How did Lincoln explain the Civil War? Who was at fault and why? How would you describe the attitude that Lincoln said was appropriate in the face of the suffering of the war?

- Are Lincoln’s views of God’s relation to humans the same in the Second Inaugural and the Temperance Address? Is there a similarity in his view of Southerners in the Second Inaugural and his view of drunkards in the Temperance Address? Lincoln spoke of relying on reason in the Lyceum Speech and appealed to the “reign of reason” at the end of the Temperance Address. Why did he not appeal to reason in the Second Inaugural? If we see the end of the Temperance Address as ironic, does that help explain why Lincoln did not appeal to reason in the Second Inaugural?

Last Public Address, April 11, 1865

- Why was Lincoln criticized for his efforts to set up a reconstructed government for Louisiana? What did Lincoln describe as some of the challenges raised by Reconstruction? Why was Lincoln opposed to determining exactly whether “the seceded states, so called, are in the Union or out of it”? What was it about Louisiana that Lincoln found praiseworthy? What did Lincoln say about black suffrage? How did Lincoln think the rejection of Louisiana’s constitution would harm both whites and blacks?

- Compare Lincoln’s remarks about black suffrage and civil rights in this speech to what he said in the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Did Lincoln’s position on black suffrage and civil rights change between the time he spoke to the delegation of black leaders and his last public address? To what extent was black suffrage implied in Lincoln’s understanding of the Declaration as he explained it in his speech at Peoria? Compare and contrast what Lincoln said about black citizenship in his speech on the Dred Scott case to this speech. To what extent do you think that the service of black soldiers in the Union Army, authorized by the final Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, influenced Lincoln to endorse black suffrage and citizenship in 1865?

Benson, Godfrey Rathbone, Lord Charnwood. Abraham Lincoln: A Biography, introduction by Peter W. Schramm. Lanham, MD: Madison Books, 1996.

Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005.

Guelzo, Allen C. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004.

Jaffa, Harry V. Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

McPherson, James. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Oakes, James. Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865. New York: W. W. Norton, 2013.