Meet Our Teachers

Kate Milburn

Kate Milburn will travel far to attend Teaching American History seminars. She has attended several multi-day programs, each time coming home eager to share new primary documents with students in Idaho’s statewide virtual charter school, Idaho Connects Online (ICON). When TAH brought a one-day seminar on the American Founding to Emmet, Idaho, she was thrilled. Milburn lives in Boise, Idaho. She’d been looking for nearby one-day seminars. The nearest she’d seen were in Salt Lake City, a 5-hour drive away. Emmet was only 45 minutes to the northwest—no problem!

The seminar, led by Adam Seagrave, covered some documents Milburn had recently discussed, at a February multi-day led by Lauren Hall on “The Apple of Gold in a Frame of Silver.” (The title quoted Abraham Lincoln’s reference to Proverbs 25:11, when explaining the relationship between the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.) Milburn realized “I was going in more prepared than the other teachers. I enjoyed listening to them grapple with questions I’d grappled with weeks before: Is the Declaration of Independence an anti-slavery document? Is the Constitution anti- or pro-slavery? How do we talk about these things?” During a break, Milburn “told the teacher sitting next to me about the other TAH seminars I’d attended, and she exclaimed, “Wait a minute. They do weekends like this?”

Sitting With the Primary Documents

Milburn’s first experience reading primary documents came after she’d been awarded the Madison Fellowship for Idaho in 2015. The award funds a Master’s program in Constitutional studies, beginning with a four-week summer institute at Georgetown University. “It was an eye-opener to be told, no, you’re not going to read an interpretation of the Constitution. You’re going to read The Federalist” (85 essays written between 1787 and 1788 to advocate ratification of the Constitution). “You’re just going to sit with these historical documents,” thinking through the arguments they made. “I had never done that before,” said Milburn, who earned a BA in political science at Boise State. “It was a life-changer.”

While in Georgetown, Milburn met fellows enrolled in TAH’s Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG). They recommended the program. Milburn had a toddler at home, so she opted for the online degree program at Sam Houston University. The program did not offer interactive seminars, but it did help her conduct original research in the Congressional Archives. Her professors helped her publish findings on the debates on impressment that led to the War of 1812. Her introduction to primary documents through the Madison Foundation prepared her for the project.

Talking About Documents at TAH Multidays

Milburn remained curious about TAH programs. While pursuing her MA, she attended a multi-day program at the Reagan library in California. “I was born right as Reagan was leaving office. I had no concept of his presidency.” She came home better informed, and “hooked on” the TAH seminar approach. Now Milburn attends TAH seminars whenever she can.

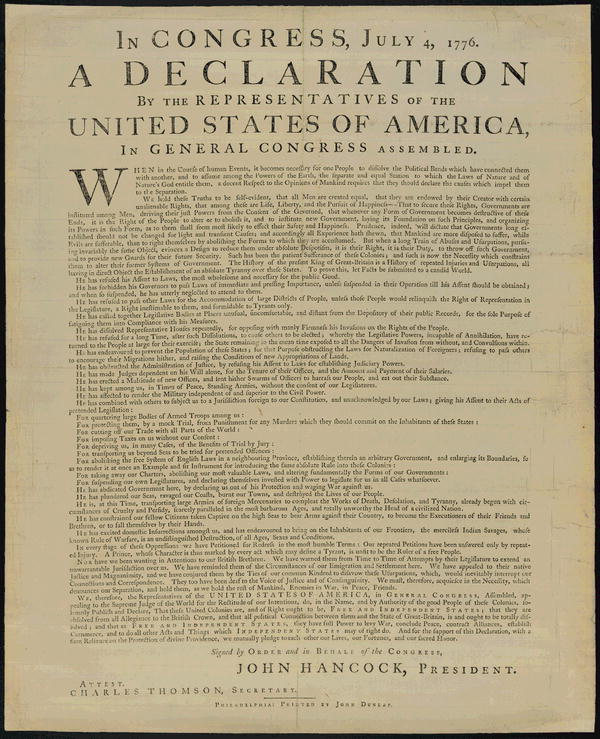

At the February multi-day, Milburn for the first time compared the original draft of the Declaration of Independence to the final version. “I don’t know how I’d never read the original. I’d seen Jefferson’s draft, written in his own hand, in an exhibit at the New York Public Library. But I didn’t know it included a diatribe on slavery”—a passage the Continental Congress removed, in order to insure consensus among the delegates.

“It never occurred to me to point this passage out to students and have a conversation about it. I’d always asked, ‘In the Declaration, when the American revolutionaries say ‘all men are created equal, do they mean all?’” When students replied, “no, not really” Milburn accepted their response—until she read Jefferson’s original. Now she will show students Jefferson’s first draft and watch them work out what they think about it. She’s concluded that the revolutionists “did mean all.” Human equality was the only logical basis for their belief in self-government. At the same time, they knew their participation in slavery contradicted their convictions.

Conversation in the Virtual Classroom

It takes effort and imagination for Milburn to replicate the discussion she enjoys at TAH seminars with her own students. ICON’s program is asynchronous. It’s designed for students who cannot attend brick-and-mortar schools. Each course encompasses eighty sessions and assignments. During 10 years at ICON, Milburn has rewritten much of the curriculum she was originally given. Each summer she retools it, so that when school opens in the fall, the entire year’s program is uploaded. Students then complete courses at their own pace, taking pre- and post-tests on each unit to show their progress. When students have not mastered the material, Milburn gives them extra ways to learn it. She spends much of the school year reviewing student work and keeping students and parents aware of what needs to be completed.

“After my first TAH weekend, I told my colleagues, ‘We’ve got to find a way to make discussions like this happen in our virtual classes.’ My colleagues said, ‘That’s not going to work.’” But Milburn began offering live interactive sessions on primary documents. She reads portions of the document aloud, then asks students questions about the text. A minority of students take advantage of such sessions, which “sometimes work and sometimes do not.” But when a primary document “hits,” and students begin discussing it, “it is so good,” Milburn says.

Teaching Sojourner Truth’s short speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?” she points to particular sentences. “Truth says, ‘If a woman upset the world, . . . give her a chance to set it right side up again.’ I ask, ‘What is she talking about?’ Recently a student responded, ‘Oh, that’s totally a Biblical reference,’ while another said, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’ The first student explained Eve’s disobedience in the garden of Eden. I didn’t have to say anything. When that happens, I know primary documents are working!”

The Founders’ Complex Humanity

Her students also read Frederick Douglass’s “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Milburn asks, “Why does Douglass keep calling Independence Day your holiday?” She watches the realization dawn on students that Douglass, speaking to a white audience, is discussing a holiday about freedom—celebrated by slaveholders. Slowly they realize “how strange and uncomfortable that is.” She probes the same point when teaching a reconstructed version of Patrick Henry’s speech demanding, “give me liberty or give me death!” Students realize the revolutionaries are “saying ‘We don’t want to be slaves,’ while also importing slaves,” Milburn says. “It’s fascinating to watch them wonder, ‘How do you square that?’”

This leads to discussions of the American founders’ humanity. “Obviously, I admire our founders very much,” Milburn says. “But it’s important to remind students that they were men—flawed individuals, just like us. I don’t think we need to excuse their negative behaviors” or to deny the fact that “their incredibly aspirational documents” changed the world. “They were complex characters, and that makes them interesting.”

The Greatest Challenge

The live sessions help Milburn meet her greatest challenge in the virtual school: “getting students to show up and care. They’re dealing with so many external issues—housing insecurity, job searches, raising a kid, mental health problems, or meetings with parole officers. Their parents may be absentee. When I can snag a student with an interesting lesson, I can get them to continue” with high school.

Discussing the human failings of the founders can also help students reflect on their own challenges. “Their life experiences help them see that the same person can be great to you or awful to you. They get that duality of man.”

She works to make students aware of their responsibility to vote and how to find information about candidates and policy issues. Beyond that, she hopes that study of primary documents will make her students aware of “the variety of perspectives” in our democracy. “You don’t have to agree with another perspective. But you have to understand it. Otherwise, you can’t find a middle ground; you can’t find a path forward.”