110 Years Ago Today: The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, A Disaster that Inspired Lasting Reforms

At approximately 4:40 pm on Saturday, March 25, 1911, the eighth floor of the Asch Building, a ten-story skyscraper on the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, erupted into flames. That part of the building was home to a business called Triangle Shirtwaist, a textile firm that produced inexpensive women’s blouses that were popular among the working class. As was typical of the textile manufactories of the time, the employees were almost all girls and young women, mainly recent immigrants from Italy and Eastern Europe, few of whom could speak English. They worked fifty-two-hour weeks (nine hours a day on weekdays, seven on Saturday), earning between $7 and $12 per week, which translated into 13 to 23 cents per hour—the equivalent of $3.45-$6.11 in 2021 dollars.

The blaze, the Fire Marshal would later determine, was likely caused by a smoldering cigarette butt or match that had fallen into a bin full of fabric scraps and tissue paper. Smoking was forbidden in the factory, but the employees were known to sneak cigarettes. In any case, with plenty of fabric and paper to fuel the flames, it only took a few minutes for the eighth floor to become an inferno. A foreman tried to douse it, but to no avail—the only fire hose was rotten, with its valve rusted shut.

When the fire broke out there were some 600 employees present, including the owners, Isaac Harris and Max Blanck—themselves self-made Jewish immigrants from Russia. The two men had founded the company in 1900, one of over 11,000 in New York City at the time. They had moved into the ninth floor of the Asch Building in 1902, right after it was built, and had expanded down to the eighth floor in 1906, and up to the tenth two years later.

With flames all around them, the employees naturally headed for whatever exits they could find, and here lay the real problem. The building had four elevators accessing the eighth floor, only one of which was fully functional. It could only hold twelve people at a time, and after four trips it broke down from the heat from the flames. There was a single iron fire escape on the outside—narrow and flimsy—and it, too, collapsed from the heat, sending some twenty people to their deaths. There were two stairwells, but the fire blocked access to one. Workers rushed toward the other, only to be stopped by a door—locked from the outside.

Firefighters were quick to arrive on the scene, but the blaze was already out of control. They frantically raised a ladder toward the people trapped on the eighth floor, but it extended no further than the sixth floor. Some workers survived by escaping to the roof and enduring the smoke until taller ladders were found. Others, desperate to escape the flames, jumped from the windows, or hurled themselves down elevator shafts, plummeting to their deaths.By the time it was all over some twenty minutes later, 146 people had died—49 directly from the fire; 36 more were discovered at the bottom of elevator shafts, while 58 others lay dead on the sidewalk.

Firefighters were quick to arrive on the scene, but the blaze was already out of control. They frantically raised a ladder toward the people trapped on the eighth floor, but it extended no further than the sixth floor. Some workers survived by escaping to the roof and enduring the smoke until taller ladders were found. Others, desperate to escape the flames, jumped from the windows, or hurled themselves down elevator shafts, plummeting to their deaths.By the time it was all over some twenty minutes later, 146 people had died—49 directly from the fire; 36 more were discovered at the bottom of elevator shafts, while 58 others lay dead on the sidewalk.

Public Response to the Disaster

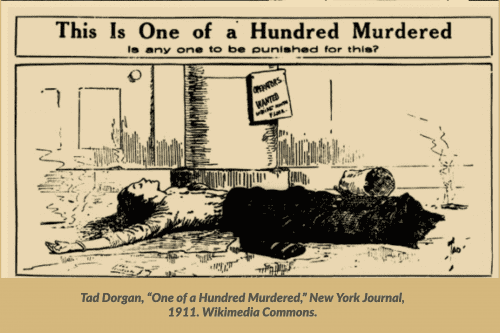

New Yorkers responded to the disaster with shock and horror. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union, which sought to organize the city’s textile employees, staged a protest march on April 5 that attracted 80,000 spectators. An outraged public pointed the finger of blame at Isaac Harris and Max Blanck. It turned out that the two men had considerable experience with workplace fires; they had occurred twice before at Triangle, and twice at another of their textile factories, the Diamond Waist Company. However, those blazes had occurred at night, when no one occupied the buildings—it was widely suspected that Harris and Blanck had started the flames themselves in order to collect insurance money. Nevertheless, they had not taken any of the recommended precautions against fire, such as installing an alarm or sprinkler system. Worst of all, many deaths could have been prevented had the door to the street simply been unlocked.

Harris and Blanck were soon arrested and charged with manslaughter. Prosecutors argued that their negligence was responsible for the deaths of most, if not all, of the 146 girls and young women who died on March 25. Their trial went on for three weeks, with more than 150 witnesses testifying. The defendants countered that conditions at Triangle violated no city or state labor regulations, except for the locked exit door, which they claimed to have known nothing about. The jury believed them, and they were acquitted of all charges.

The real lasting effect of the fire was the series of new regulations it inspired. New York’s state legislature quickly formed a commission to investigate the blaze; State Senator Robert F. Wagner was appointed its chair, and State Assemblyman Alfred E. Smith was named vice chair. They worked closely with Frances Perkins, a professor of sociology at Adelphi University. Soon after the Triangle fire, Perkins was appointed executive secretary of the newly created Committee of Safety of the City of New York, which formed to recommend ways of increasing fire safety. The commission interviewed 222 witnesses and recorded 3500 pages of testimony. Investigations by field agents associated with the commission identified over 200 factories that had some of the same risks as Triangle. Their work resulted in 38 new laws regulating labor in the state, including requirements for better exits, fireproofing, fire extinguishers, and alarm and sprinkler systems. It also served as a launching pad for their careers; Wagner would go on to the U.S. Senate, Al Smith would become Governor of New York (and unsuccessful Democratic candidate for president in 1928). Perkins in 1933 was appointed Secretary of Labor by President Franklin D. Roosevelt—the first female cabinet member in U.S. history.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire was the worst workplace disaster to occur in New York City, and it would retain that distinction until the collapse of the Twin Towers on 9/11. The reforms that it inspired, however, remain with us to this day.