2020’s Complicated Election Process

This blog piece first ran in October 2020, prior to the last presidential election.

During the pandemic far more voters than ever before used mail-in ballots. Some are questioning whether our existing procedures for computing election results can handle the situation in a way that maintains voters’ confidence. With delays in reporting the state outcomes, temptations to question the process multiply, especially in a sharply divided partisan climate. This situation seems ripe to produce more contested election results.

We asked Professor Jeremy Bailey, Professor in the Department of Classics and Letters at the University of Oklahoma and a faculty member in the Master of Arts in American History and Government program, to help us explore this possibility in the context of history and in the light of Constitutional principles. Bailey is the author of The Idea of Presidential Representation: An Intellectual and Political History (University Press of Kansas, 2019), James Madison and Constitutional Imperfection (Cambridge University Press, 2015), Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power (Cambridge, 2010), and the editor of our core document collection, The Presidency. That collection is currently being offered as part of a three-volume promotion including Congress (edited by Professor Joseph Postell) and Political Parties edited by Professor Eric Sands).

1. In our system, it is not the majority of popular votes that decide presidential elections; it is the majority of votes in the Electoral College. Yet on three occasions, no candidate received an Electoral College majority. What happened in each case?

The original plan for voting in the Electoral College did not differentiate between candidates for president and vice-president. It’s only after passage of the 12th Amendment that Electors designated who would be President and Vice-President. But the earlier arrangement resulted in our first contested election, in 1800—because the two highest vote-getters were tied.

The Election of 1800

Everyone understood that the Democratic-Republican candidate Thomas Jefferson was competing with the incumbent and Federalist candidate John Adams for the presidency. However, due to a snafu, Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr received the same number of votes. Someone in Jefferson’s party had forgotten to discard one of their ballots to avoid this situation. As stipulated in Article II, Section 3, this meant that the choice between Jefferson and Burr had to be decided in the House, where each state delegation gets one single vote. This resulted in a partisan contest, the Federalists trying to block the election of Jefferson because of his well-known opposition to Federalist policies. As we know, it took 36 ballots and the efforts of Alexander Hamilton—who thought Burr’s unprincipled ambition more dangerous than Jefferson’s Republican views—to persuade several Federalists to throw away their votes and break the tie.

The problem that threw the 1800 election into the House was fixed in 1804 by the 12th Amendment and its “designating principle.”

But what’s important about the election of 1800 is not its contested process. It’s that, for perhaps the first time in human history, power passed peacefully from one party to the other, with the incoming Jefferson administration adopting a posture of conciliation and harmony. Even though John Adams did not stay long enough in the capitol to hear it, Jefferson in his inaugural address declared, “We are all Federalists; we are all Republicans”—saying, in effect, we share the same principles. The election of 1800 showed that partisan election battles did not threaten our constitutional system.

Election of 1824

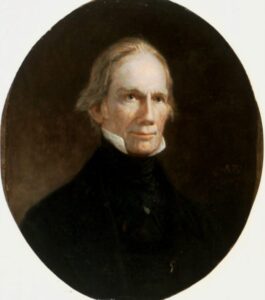

In fact, the next difficult election—that of 1824—occurred because the party system had temporarily broken down. That brought a recourse to sectionalism, resulting in a four-way contest for the presidency. Due to the Twelfth Amendment, the winning candidate now had to secure a majority of the Electoral College votes. Because none of the four candidates did, once again the election had to be decided in the House, between the top three vote-getters: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and William Crawford. Henry Clay, who came in fourth, convinced his own Kentucky delegation to vote for Adams—outraging Jackson, who had won a plurality of the Electoral College votes and whom Kentuckians no doubt preferred over Adams. You could say that the lingering anger over this election triggered the formation of a Jacksonian Democratic Party.

Election of 1876

The third contested election occurred in 1876. A very close election, its results were contested in three states. In Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, each party claimed its candidate won. Without those states’ votes, Democratic candidate Samuel Tilden remained one vote shy of an Electoral College majority, with Republican Rutherford Hayes further behind. In this situation, the House would normally decide the outcome; but the existence of competing slates of electors in the states with contested elections argued for another solution. Congress decided to form a 15-member commission split evenly among representatives from the House, the Senate, and the Supreme Court. The party affiliation of the commission members were divided in the same way, with one of the five Supreme Court justices supposed to be a moderate of unknown party affiliation. Most historians think that an agreement was reached within the commission to give both parties something they wanted. The presidency was awarded to the Republican Hayes, in exchange for policy the Democrats wanted: an end to Reconstruction.

2. Many Americans today question the Electoral College system, noting that in both 2000 and 2016, the winning candidate lost the popular vote. This had not happened since 1888, when Grover Cleveland won more votes than Benjamin Harrison, but lost in the Electoral College. (In none of the cases mentioned did the losing candidate win a majority of the votes cast; the only time that happened was in 1876, when Tilden won 50.9 % of the popular vote.) Has the Electoral College become outmoded?

Election of 1960

Sanford Levison of the University of Texas Law School, one of America’s foremost Constitutional scholars, would add the election of 1960 to your list. He thinks Nixon received more votes than Kennedy did, when one includes some votes wrongly excluded in the South. Usually it is said that in Illinois and Texas, which were both very close, the counts may have been off. Nixon conceded the day after the election, yet quietly organized Republican attempts to contest the results, but these ran out of steam.

Role of the Electoral College

This variance between popular and Electoral College votes occurs because we count votes by states. Squeaky victories in a handful of states are more important than runaway victories in other, perhaps more populous states.

We should remember that the Electoral College system is just one of several features of our Constitution resulting from the fundamental issue confronting the framers: the question of state equality versus proportionality of representation. The small states perceived correctly that the large states would dominate the presidency, so they had to exact as many concessions as they could in order not to get steam-rolled by the larger states. In addition to the Electoral College, we’ve noted that the procedure for resolving disputed elections in the House gives each state delegation a single vote. The framers also gave states an equality of votes in the Senate and made that the one thing that’s not changeable by Constitutional amendment. From my perspective, the Constitution is incoherent if you don’t understand that compromise.

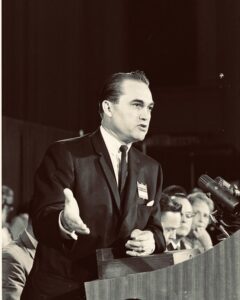

Election of 1968

One of the accidental effects of the Electoral College is that it creates battleground states. In these states, which have a variety of sizes and are in a variety of regions, every single vote matters. During the 1968 election, when both parties recognized the threat posed by an independent regional candidate like George Wallace, both wanted to amend the Constitution to abolish the Electoral College. In addition to officials from small states who held the usual concerns, African Americans opposed this move, because they perceived that the votes of minorities weighed more in battleground states than in the popular vote count. I don’t know if that’s still the case today.

Today, most third-party candidates win no electoral votes. They may prevent either candidate from receiving a majority of the popular vote, but they don’t prevent one from achieving an Electoral College majority. Wallace, however, who ran as a segregationist, actually won five southern states. In our current climate, I can imagine someone like Bernie Sanders winning a couple of states in the Northwest, or a conservative candidate winning a couple of the Rocky Mountain states, and messing things up.

3. The contested elections of the 19th century went to the House for resolution (although, in 1876, the outcome was decided by a Congressionally appointed commission). But in the last contested election, that of 2000, the House was not involved. Why not?

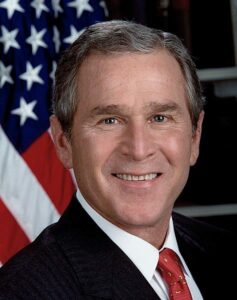

That case could have been decided in the House, because on the morning following election day, neither George W. Bush nor Al Gore had secured a majority of the Electoral College votes. In Florida, which controlled a decisive 25 electoral votes, the margin of victory for Bush was so slim that state law required a recount.

Election of 2000

The example of 2000 is the most important for our situation today. It reminds us that in our system of federalism and separation of powers, we have many different contending centers of authority. A candidate seeking to contest the election results will seek those centers of authority that favor his candidacy. In 2000, because Republicans controlled the majority of state delegations to the House, Al Gore did not want the decision taken there. He made it very clear that any election decided in the House would be considered illegitimate by his party. For Gore to win, he had to have the election settled decisively by the Florida Supreme Court, which leaned Democrat. He did not want it to be settled by the Florida Secretary of State or the Florida Governor, who were Republicans, or by the Florida legislature, which was also controlled by Republicans. Bush’s opposite strategy was to get the decision out of the Florida courts and into the federal courts, which ultimately led to a decision in the US Supreme Court.

The Constitution allows the states to decide electors in any way the state legislature chooses. Hence, we have 50 states and 50 different sets of rules determining the standards for recounts and challenges. Also, the political environment is different in every state. If you have two states where the count is very close, the same candidate may be seeking resolution through the courts in one state, while seeking it through the executive branch in another. If you are George Bush in 2000, you are relatively comfortable that even if a recount leads the Florida Supreme Court to rule that a new set of electors be assigned, the Florida state legislature will immediately create their own set of electors who will be certified in your favor by the Florida Secretary of State. That would lead to a question in Congress over which set of electors to accept. The House presumably would have ruled in Bush’s favor, because the majority of state delegations were Republican. Alternatively, if the House voted to exclude Florida’s votes altogether, then Bush would still win.

Election of 2000 and the US Supreme Court

Gore asked for a complete recount, then used the Florida legal process to demand a hand recount in three southern Florida districts that were Gore-leaning, not in the whole state. Meanwhile, when Florida’s Secretary of State certified Bush as the winner, Gore appealed to the Florida courts. In response, Bush looked to the federal courts, which ultimately pushed the decision to the Supreme Court. Seven justices agreed that recounting some but not all of the votes in Florida violated the equal protection clause of the 14th amendment. A bare majority of five agreed that there was insufficient time for recounts to continue. It is perhaps worth noting that had Gore won in court, he would have still lost to Bush in the vote count (and a subsequent recount organized by the Press Corps of the Miami Herald, CNN and the New York Times showed that had Gore been able to pursue his preferred strategy of counting “undervotes,” he would not have surpassed Bush. The “overvotes,” a strategy he did not pursue, would have been different.)

4. When did voting by mail become possible in the US? In the context of our historical practices for elections, should we worry about mailed in ballots?

We’ve had vote by mail for a very long time, in the form of absentee ballots. But that’s different from universal voting by mail, which exists in only a handful of states. Moreover, some states have really strict requirements about absentee balloting, while others will give absentee ballots to anyone who requests them.

Neither of our parties is talking about this in an honest way. Trump muddied the waters by shouting that mail-in voting is fraudulent. On the other hand, the Democrats have not acknowledged that adding to our absentee balloting regime in large numbers is going to slow down our process tremendously. And in some states like Pennsylvania, counting cannot begin until several days after the election. Meanwhile, US law sets the “safe harbor day” for reporting Electoral College votes in early to mid-December; this is the date that came into play in Bush v. Gore.

Counting Mailed in Ballots

The counting will occur in an environment that is potentially contested, with every ballot observed by lawyers from both sides to determine if it’s a “legal” ballot—and notice that absentee ballots invite more scrutiny as to whether they were legally cast. In states where the results are close, the losing party will contest the count, if that is their right under state law. Courts and executive branches will disagree about the proper legal remedy under each state’s law. Obviously, the American people are not acculturated to the prospect of long counts when everybody knows that those counts will determine who wins and who loses. We saw this in the Iowa caucus earlier this year.

One solution—we’ve already seen a couple of congressmen propose it—would be to push back the safe harbor date into January. One problem with this that it potentially creates opportunities for partisan actors at the local level to harvest questionable votes. Some worry about civil unrest, people taking matters into their own hands because they are frustrated by the delay. I’m more concerned about the effect on a presidential transition. The incoming Bush administration in 2000 perhaps didn’t take as much time as they should have in their intelligence briefings, because they were dealing with Florida. Yet you can expect that if Biden starts forming something that looks like a cabinet (as Bush did in 2000), Republicans (like Democrats in 2000) will condemn that as inappropriate.

The presidency is a tough job and the transition period is important. There needs to be an exchange of information between the outgoing and incoming administrations, but a contested election narrows that window, while also poisoning the well for communication.

5. What elements of our election process do you wish the American people better understood?

I wish that the American people understood the House as the Constitutionally intended arbiter of contested elections. State law matters, of course, and when you think about state law, you’re thinking about state courts. But we shouldn’t think of the Supreme Court as the grand appeal here. We should think of the House as the grand appeal—that makes for more Constitutional harmony.

Second, we need to either explain more clearly the differences in states’ laws with respect to voting, or we need to bring those laws into uniformity. Given the current polarization, there is too much opportunity to see differences in the states’ electoral processes as some sort of deviant intent. Yet most states’ electoral laws come from an earlier era. If we prefer diversity in state laws, then we need to have an account of why that kind of diversity is in fact good.

Third, I think mail-in voting is a little reckless. I understand there are concerns about the spread of COVID, but mail-in balloting comes with a clear cost and the cost has not been sufficiently explained. We need to do a better job of explaining the costs of imposing this extra work on our state election authorities.