50 Core American Documents: The Seneca Falls Resolution

To showcase our latest Core Document Collection (CDC) volume, 50 Core American Documents, we’ve asked 3 of our teacher partners to choose their favorite document from the volume and explain the document’s history and how they use it in their classroom. Our first post is from Lauren Goepfert, a U.S. History teacher from New York and recent MAHG graduate.

The Importance of Consent and Equal Rights

From 1776 to 1920, American women lacked many of the civil rights of men, including the right to vote in federal elections. Our Declaration of Independence states that the government gets its “just power from the consent of the governed.” Normally, citizens indicate their consent by sharing in the process of electing those who pass and execute the laws–that is, by voting. The issue for women of the mid-19th century was: had anyone asked whether they consented to the government they were under?

Every year in U.S. History class, teachers cover early reform movements from 1800 to 1860. In this unit we discuss the problems that faced the country in the early decades after the Revolution–and the solutions suggested by reformers of the time. One such issue was the treatment of women before the law. Most students can recognize the Seneca Falls Convention and link it to women’s suffrage. However, that is just part of a larger picture.

By 1848, women were becoming more active politically because of their increased involvement within social movements. Many women participated or supported temperance and abolitionist movements. In fighting for others, they saw the inequalities they themselves faced. Not only did women in the US lack the right to vote; they were not treated equally before the law. Once a woman was married she was under the care of her husband. She could not own property, attain higher education, serve on a jury, initiate a divorce, or, if divorced by her husband, he would be given full custody of their children. Her husband was legally able to physically discipline her if he saw fit. It was also thought that men, as the heads of families, represented their wives and daughters at the polls. Women were being virtually represented while being looked at as inferior to men.

Seneca Falls: The First Women’s Rights Convention

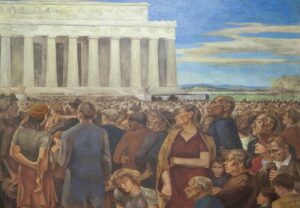

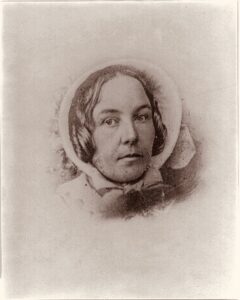

After being placed in a separate seating area for women and not allowed to speak at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840, one group of women had had enough. Led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, they organized the first women’s rights convention, the Seneca Falls Convention. It was here that Stanton paired with Mott to write the Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions. (Most students, when they think of Stanton, always think of Susan B. Anthony; but Anthony was not in attendance nor was she working with Elizabeth Cady Stanton yet.) The two-day Convention was attended by women AND men who wanted to see the ideals within the Declaration of Independence put into practice for both sexes. While this was the first convention, it would not be the last.

Teaching the Seneca Falls Resolutions

In my classroom students usually read primary documents in their entirety, because I want them to come to their own conclusions. I do not want my students to either just take my word or take the word of a textbook synopsis, but to read the argument from the pen of the author. The excerpt in the new 50 Core American Documents volume excludes the Declaration of Sentiments, but these can be found in another TAH document collection, Gender and Equality. This first half of the document is made up of a preamble and list of grievances. While teaching the Seneca Falls Resolutions, I ask my students to compare these parts of the document to the Declaration of Independence, which is structured in the very same way. My intent is to get my students to notice the similarities in language. Many revolutionary groups have copied the language of the Declaration of Independence to use within their movements: the Filipino fighters against American control of the Philippines, John Brown in his Declaration of Liberty, and even the Black Panthers’ in their Ten Point Program. Each of these movements wanted a goal of self determination and recognition of their natural rights, and used the language which sets the founding ideals of our country.

The excerpt in the 50 Core American Documents volume is focused on the resolutions. Here, students can read the ultimate goals that women wanted to attain. When I use this document in my classroom, my students read through the resolutions to identify the problems women faced in the mid-19th century. There is nothing stronger than reading their words and the description of the problems they faced. Women were asking to have the same rights and treatment as men before the law. They asked not just to vote but to be treated the same. It leads to a conversation about inequality and how to attain full equality.

The excerpt in this volume is taken from a history of the women’s movement that Stanton later wrote in collaboration with Anthony and Matilda Gage. At the end of the excerpt, the TAH volume editor included some remarks from the history about the debate over the resolutions, summarizing what Frederick Douglass and Stanton said about one of the demands. This allows students to see the overlap of leaders and support in the various reform movements. Frederick Douglass worked not only for abolition but also for women’s rights. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were not just abolitionists and women’s rights activists but also started prominent temperance societies. Lucretia Mott also began her fight for equality by working in the abolitionist movement. Sojourner Truth, who wrote “Aint I a Woman,” voiced the causes of abolition and women’s rights at the same time. When students notice this overlap of leadership, they typically ask how these remarkable reformers had so much time to participate in multiple movements! Students ask about why would those concerned about the welfare of women work for temperance? Student comments like these lead us to larger conversations about the connections between reform movements and how it relates to issues seen in society today.