A Full-Throated Defense of Federal Protection for Civil Rights – in 1875

MAHG graduate Ray Tyler takes a deep dive into Rep. Robert Brown Elliott’s compelling and prescient defense of the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

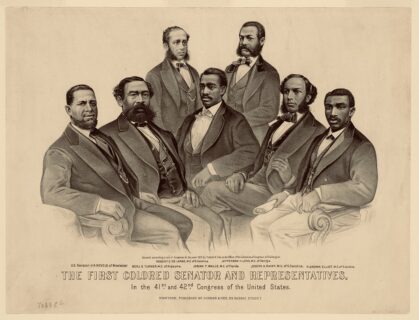

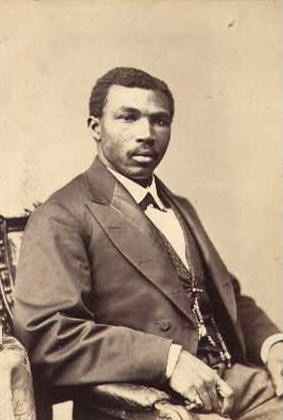

Of the fifteen African Americans elected to Congress from the former Confederacy during Reconstruction, six were South Carolinians. Perhaps divine retribution for being the first state to secede from the Union explains this dramatic reversal of fortunes for previously enslaved Black South Carolinians. More likely, it was simple math. Blacks outnumbered whites in South Carolina in 1870, and they were anxious to exercise their power. That year, Black voters – many likely voting for the first time – and their white Republican allies sent Robert Brown Elliott, a native of Liverpool, England, then practicing law in Columbia, SC, to Washington as a member of the House of Representatives. On January 6, 1874, Elliott debated the former Confederacy’s Vice-President Alexander Stephens over the need for a federal Civil Rights law barring discrimination in public accommodations. In his speech, Elliott expressed anguish that might resonate with many Americans today. He regretted it was necessary – in 1874 – to rise in support of “a bill which simply asserts equal rights and equal public privileges for all classes of American citizens.” He also regretted that his race would lead some Americans of his era to conclude that his motivation was personal and not a simple call for justice.

In a recent brainstorming session on topics for our We the Teachers blog, my colleague Amanda Bryan suggested a post on Elliott’s speech, Document 2 of Teaching American History’s latest core document collection: Race and Civil Rights (edited by Dr. Peter C. Myers, Professor of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire). Amanda speculated that most American teachers were unfamiliar with the document, and many would find it surprising and compelling. I was one of those teachers when I was teaching.

The 1874 debate over the Civil Rights bill took place one year after the Supreme Court’s decision in the Slaughterhouse Cases, a collection of several Louisiana cases claiming a state law granting a monopoly to a New Orleans butcher violated the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. In Slaughterhouse, the court made a distinction between the rights of citizens of the United States and those of citizens of an individual state. States could define the rights they granted their citizens, as long as they accorded all persons, regardless of race or any other distinction, the same rights. The monopoly was deemed allowable under this standard. Thus, the decision emphasized the “equal protection” clause of the 14thAmendment while severely restricting the application of its “privileges and immunities” clause against discriminatory state legislation. Elliott argued that the passage of the Civil Rights Act would not contradict the Court’s decision in Slaughterhouse. Rather it would protect those rights all Americans enjoyed throughout the country.

There are several reasons why American history students and teachers might find Elliott’s speech important. First, the Civil Rights bill – enacted in 1875 – contained provisions commonly associated with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, specifically the right to use public accommodations without discrimination. Teachers can ask students to consider why it took one hundred years for the federal government to firmly support the right to public accommodations regardless of race. What conditions existed in 1964 that did not in 1874?

In 1874, Elliott astutely chose not to dispute the merits of the Slaughterhouse decision. Instead, he argued that the rights he wished to protect were those he currently enjoyed under the Constitution: the right to travel on public conveyances, the right to public inns and restaurants, the right to education in public schools, and the right to burial in public cemeteries.

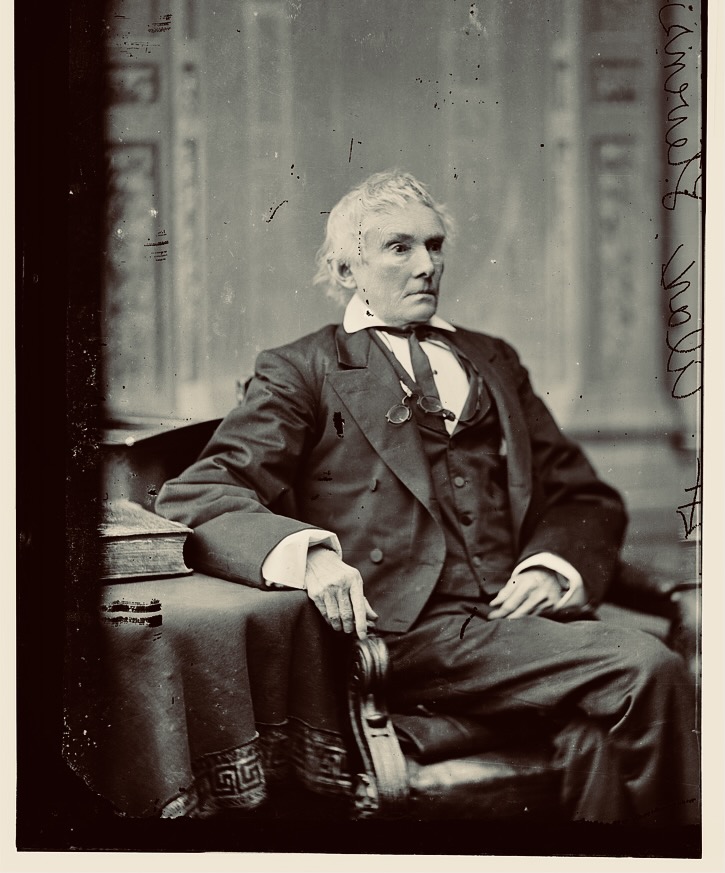

Another reason Elliott’s defense of equal rights for African Americans would interest students is the fact that it singles out the views of one of the bill’s key opponents, Alexander Stephens of Georgia, the former Vice-President of the Confederacy. In his inaugural address, Stephens made the infamous claim that the Confederacy’s “foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.” What did Stephens think as he heard the highly educated, accomplished South Carolinian articulate a new vision of America that placed Black citizens on equal footing with those who were white? Aware that Elliott graduated from a prestigious prep school in England, served in the Royal Navy, studied law and practiced it in South Carolina, was he forced to admit Elliot’s worthiness as a colleague in the US House of Representatives? Did he re-evaluate his claim of white superiority and black inferiority?

Elliott begins his critique of Stephens respectfully, acknowledging Stephens’ “long experience in public affairs.” Then he denounces the principles Stephens has hidden under claims of states’ rights. He says Stephens shocked “the civilized world by announcing the birth of a government which rested on human slavery as its cornerstone.” Stephens had participated in a government of “greed, pride, and tyranny,” trespassing on the rights of African Americans who “even in the darkness of slavery kept their allegiance … to freedom and Union.” Stephens fought to wreck the Constitution and Union while Elliott and other African Americans fought to preserve it. Elliott invites Stephens to reassess his views and join him in perfecting the Union.

Teaching American History’s Core Document Collection: Race and Civil Rights picks up the story of the African American struggle for full equality after emancipation. The Civil Rights Act Elliott supported was passed in 1875 but ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883. It took more than 80 years for the rights Elliott insisted upon to be fully enforced in the United States.