A stack of $1000 bills Sixty-Seven Miles High

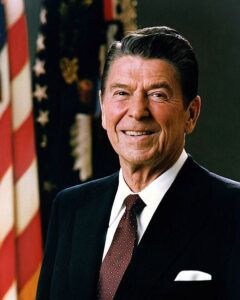

“One trillion dollars of debt—if we as a nation needed a warning, let that be it.” With these words, President Ronald Reagan described the ominous trillion-dollar milestone that the United States’ national debt passed forty years ago, on October 22, 1981.

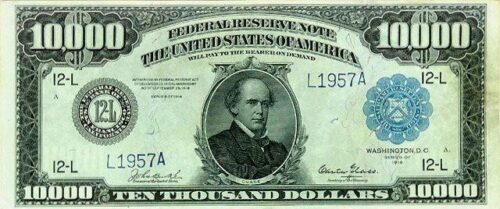

Reagan earned the nickname the Great Communicator for his ability to explain the scope of the problems affecting the United States. To describe the mind-boggling debt of one trillion dollars, Reagan visualized a trillion dollars as a stack of $1000 banknotes stretching skyward and into outer space. In comparison, a personal fortune of a million dollars would not stack much higher than a hand width. Soon after his election, Reagan explained this in a televised address to a joint session of Congress on the national debt:

Our national debt is approaching $1 trillion. A few weeks ago, I called such a figure, a trillion dollars, incomprehensible, and I’ve been trying ever since to think of a way to illustrate how big a trillion really is. And the best I could come up with is that if you had a stack of $1,000 bills in your hand only four inches high, you’d be a millionaire. A trillion dollars would be a stack of $1,000 bills sixty-seven miles high.

The staggering scope of the national debt created immediate problems, Reagan argued. First among them, Reagan pointed out, was that his administration would have to make almost $100 billion in interest payments every year to the federal government’s creditors.

In 1981, economists were increasingly taking a more critical view of deficit spending. To that point, the economic orthodoxy of John Maynard Keynes held that governments should play a leading role in economic recoveries from recessions, since governments could borrow and spend money—run budget deficits—when individuals and businesses could not. Critics argued that this approach not only failed to alleviate the economic recessions of the 1970s, but also that it could not account for rising inflation amid high unemployment. One explanation offered by these critics, who included some of the architects of so-called “Reaganomics,” was that increasing levels of public spending “crowded out” private investment. Every dollar invested in government bonds, for example, was a dollar not invested in a private business. These critics argued, then, that a growing national debt “crowded out” private investment and slowed economic growth.

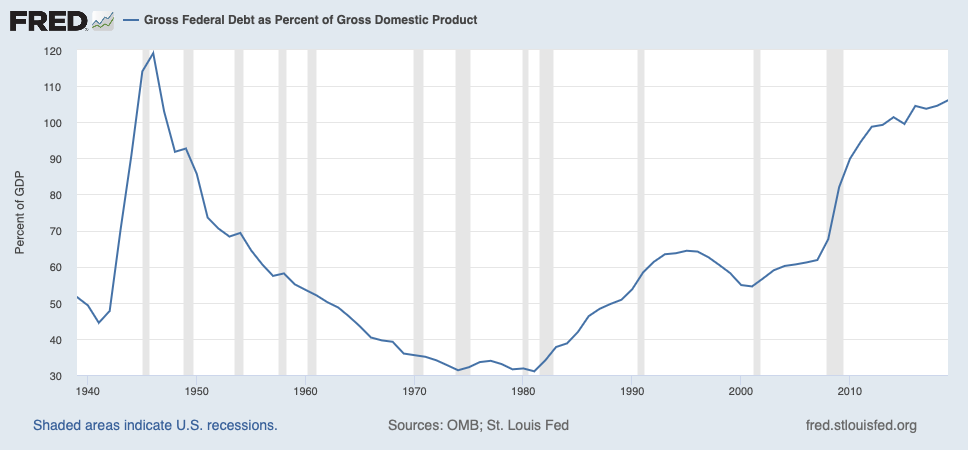

Despite Reagan’s warnings forty years ago, history seldom if ever remembers him as a deficit hawk who sought to bring deficit spending under control. Public debt rose in the 1980s amid tax cuts and increased military spending. During the Reagan Administration, Congress raised the debt ceiling eighteen times. By the end of the decade, the national debt had doubled to more than $2 trillion. The ratio between public debt and U.S. gross domestic product, which had actually been decreasing at the time of Reagan’s warning in 1981, steadily increased during his term in office. Faced with a choice between outlasting the Soviet Union in an arms race and paying down the national debt, the conventional thinking goes, Reagan chose to outspend the Soviet military. Since Reagan lambasted the federal government’s “dangerous addiction” to deficit spending, only to increase spending and worsen this addiction, he is charged with being a hypocrite on deficits. Perhaps worse, depending on what circles one travels in, he is accused of being a Keynesian.

Reagan’s detractors forget that interest rates hovered around 20% at the beginning of his first term. Therefore, they fail to take into account that the increase in the national debt was largely the result of higher interest payments, and not new spending. Shortly before Reagan took office, the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker raised interest rates sharply in order to bring inflation under control. Economists who reexamine the whole historical picture now argue that most of the increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio during the 1980s was a result of interest spending, not Reagan’s tax cuts and military spending increases. This ought to put to rest the commonplace that Reagan was simply a hypocritical fiscal conservative. It should also put his concerns about the debt in a new light: Reagan warned the nation about a rising debt he was largely powerless to prevent from increasing.

Reagan viewed himself as rediscovering American common sense. In his Farewell Address, he disavowed his famous moniker: “I wasn’t a great communicator, but I communicated great things… they came from the heart of a great nation — from our experience, our wisdom, and our belief in the principles that have guided us for two centuries.” He rediscovered at least two common-sense principles about the national debt in particular that date to the Founding.

The Founders brought forth a new nation conceived in debt and inflation. By the middle of the War for Independence, the United States was deeply in debt to France, Spain, and the Netherlands, and its paper “continentals” were worthless. Thomas Jefferson expressed his worries to James Madison that debt imperiled the possibility of self-government: if one generation’s “debts & incumbrances” can be charged to a later generation, “then the earth would belong to the dead & not the living generation.” Excessive debt is an intergenerational injustice. This is the first part of the Founders’ common sense that Reagan recovered: we must be careful about spending our great-grandchildren’s inheritance.

The second principle Reagan recovered is that excessive national debt will hamper economic growth. In an exaggerated precursor to Reagan’s trillion-dollar warning , Jefferson wrote in a letter of “public debt as the greatest of the dangers to be feared.” Although his famous arch-rival on the issue of the national debt, Alexander Hamilton, disagreed, he admitted an important qualification to this warning in his famous statement to Robert Morris: “A national debt if it is not excessive will be to us a national blessing.” Yet a younger Hamilton pointed to the “debt unparalleled, in the annals of any country” of Great Britain as an argument for revolution. Jefferson and even Hamilton sensed that excessive national debt would impoverish a country by misdirecting capital that would be better put to more productive purposes. Reagan found himself in a position not unlike the Founders: committed in principle to a system of “perfect freedom” with “no regulations of trade”, but also responsible for leading a debtor nation facing a powerful military rival.

Americans paid down the debts of the American Revolution in the 1830s, some forty years after the Founders’ warnings, but we are not on a similar path after Reagan’s admonition. The national debt will reach $29 trillion in the coming months. We added $1 trillion to the national debt in a matter of months following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. China and Japan alone hold about $1 trillion of the national debt, respectively. And private investment by the Americans who hold the national debt is perhaps crowded out now more than ever. The Congressional Budget Office projects that each additional dollar of federal debt decreases domestic investment by an estimated thirty-three cents. These mind-boggling numbers can make our eyes glaze over. Warnings from the distant and not-so-distant past, however, exhort us to remain clear-eyed about the challenge we face.