1919 - A Year of Racial Violence: An Interview with David Krugler

A century ago, in the wake of a rapid demobilization of soldiers returning from World War I, ten major race riots occurred in American cities, along with other acts of collective violence targeted against African Americans. Professor David Krugler wrote 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015) to document the actions taken in black communities to resist the violence. Krugler, Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin–Platteville, also teaches such courses as “The Rise of Modern America, 1914-1945” and “The United States, 1945-1973” in the MAHG program. He spoke with TAH editor Ellen Tucker about his book’s findings.

Your book, 1919, The Year of Racial Violence, recounts an eruption of “anti-black collective violence” in major cities of both North and South during 1919. Why did this occur in that year?

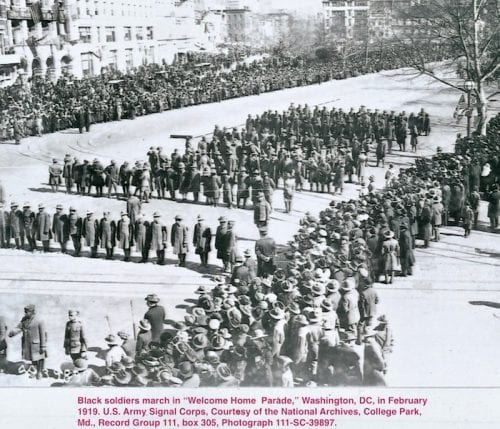

It was a year of dislocation following great social change. During the First World War, the “Great Migration” had accelerated, bringing 500,000 African Americans from the South to Northern cities like Pittsburgh, Chicago, and Detroit. Corporations often incentivized these moves; they needed labor, due to lower immigration during the war. Then, when the war ended, one of the most rapid demobilizations in the nation’s history occurred, with hundreds of thousands of returning soldiers discharged at eastern seaboard ports. They had to find their own way home and look for employment. So in northern cities, there was new economic competition, causing racial unrest in Gary, Indiana, and Chicago.

The Great Migration also caused housing changes, especially in Chicago, where African Americans lived in a narrow “Black Belt” of high-rent yet very substandard housing. When black Americans started moving out of the Black Belt to neighboring streets, white ethnic groups, especially Irish Americans, reacted angrily. For example, in Chicago, blacks who moved west across Wentworth Ave to Canaryville and Bridgeport—heavily Irish neighborhoods—might find their homes bombed or attacked by white gangs.

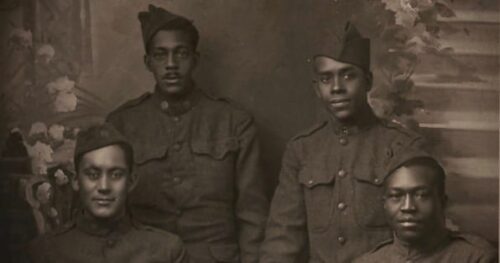

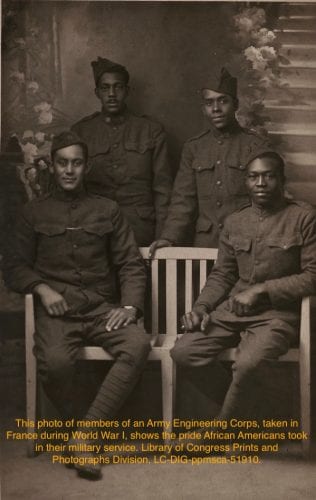

A third factor was that black veterans returning from military service—whether they stayed stateside or saw time in France—had absorbed Wilsonian rhetoric, along with the rhetoric of the New Negro movement. They had fought for democracy abroad and now expected it at home. Some returning veterans wore their uniforms with pride. Veterans could do this after discharge as long as they wore a chevron indicating they were no longer on active duty. But many whites saw black men in military uniforms as a provocation. Black veterans were attacked or even lynched for wearing their uniforms.

You’re saying that after the war, African Americans pursued opportunities to earn more, live in better housing, and simply enjoy the freedom of an urban environment. When whites reacted to this with violence, blacks fought back. How did they do this?

They resisted on three fronts. First, they organized armed resistance against the white mobs targeting homes and black citizens on the streets.. Black veterans and others in their communities formed patrols and began doing the job the police were unable or often unwilling to do. Second, they fought for the facts, for accurate recording of the causes and course of the violence. Third, they pushed for fair administration of justice after the violence. In the book, I argued that the three efforts were interrelated.

When African Americans took up arms to defend themselves, it was often reported that they had attacked whites without provocation. An extreme example of this occurred in Phillips County, Arkansas, where whites targeted blacks involved in a union effort to get fair prices for their sharecropping contracts and escape debt peonage. The population of Phillips County was about 75% African American. Mainstream newspapers reported that white citizens formed posses because African Americans were conspiring to kill all the whites. Actually, whites were conspiring to frame the sharecroppers in the tenants’ union. When you’ve got twelve of those sharecroppers charged with conspiracy and murder and quickly convicted with death sentences, any effort to overturn their appeal will need accurate facts about what happened.

You write of NAACP workers traveling to the places where people were unjustly charged to gather evidence. How much help did the African Americans who organized for self-defense receive from black activists elsewhere—or from anyone in the white community?

You’ve got Walter White (whose mixed race allowed him to pass for white and to collect information that others in the NAACP would have had difficulty collecting)—he went to Chicago and collected facts about police practices and black self-defense. His arrival coincided with the “Grand Jury strike,” in which the all-white, all-male Grand Jury convened by the state’s attorney in Cook County asked, “when are we going to see charges brought against white defendants?” The state’s attorney had been bringing African Americans who’d been defending themselves against white attacks before the jury to be charged with murder. He bristled at the question, saying words to the effect of, “The state’s attorney is doing his duty . . . and needs no suggestions from anyone as to how he should do his duty.” The Grand Jury held their ground and adjourned. White immediately set to work gathering evidence against white attackers. This pressured the state’s attorney to charge a few white attackers.

In Phillips County, Arkansas, the twelve men found guilty were never acquitted, yet all their death sentences were eventually vacated or abandoned. The NAACP had some white allies in that case.

Overall, what did African Americans who resisted the violence in 1919 accomplish?

They won numerous short-term victories, especially in establishing a record of what really happened. They established a foundation for the Harlem Renaissance, the bridge between the New Negro movement of the pre-World War I era and the post World War I era. They also established the precedent for armed resistance to organized white, anti-black collective violence after World War II. In the book’s conclusion, I try to draw out connections to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, pointing to great books like Lance Hill’s Deacons for Defense and Robert Williams’ Negroes With Guns.

Yes, your book changed my thinking about the later Civil Rights Movement. You write that groups who provided civil defense reinforced the civil rights efforts of Martin Luther King and other nonviolent resisters.

A lot of the early studies of black power looked at it as an aberration—where did civil rights go wrong in allowing militant black power to emerge? We need to understand that even while King used peaceful nonviolence to advance civil rights, a quiet armed resistance gave him support. When the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) went to Bogalusa, Louisiana, and its activists were targeted, local blacks, including some veterans of WWII, showed up with guns in their trunks, and began patrolling. Although committed to nonviolence, CORE accepted the protection of these armed men.

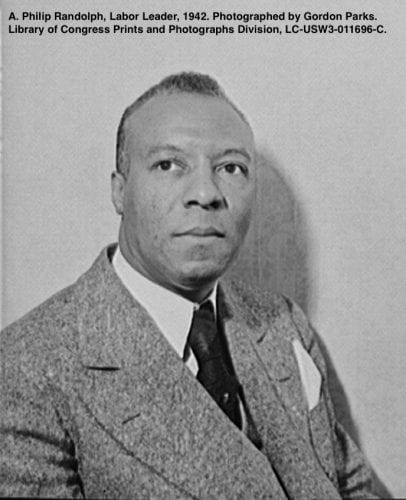

There is a long arc to the African American civil rights movement. We think it all happened under King’s leadership; but he built on the work of others. A key figure embodies the continuities: A. Philip Randolph. As editor and publisher of The Messenger, he advocated black self-defense in 1919. He also organized the March on Washington movement in 1941; that’s why he’s one of the keynote speakers during the March on Washington in 1963.

Randolph had shown you could bring pressure from large numbers of African Americans to bear on the president, changing his policy. In 1941, Randolph recalled 1919, when black Americans returned from a war to “make the world safe for democracy” and found democracy under siege at home. Now another president, Franklin Roosevelt, was talking about mobilizing to protect democracy, and Randolph thinks, “Promises are not enough.” Having already honed the skills to go head to head with a president as wily and evasive as Roosevelt could be, he announced a plan for a march on Washington. To avert that, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 barring discrimination in defense industries and federal bureaus and creating the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to monitor compliance. Jennifer Keene’s core document collection on World War II includes a subsequent statement from Randolph, saying, “If the FEPC doesn’t open enough employment opportunities, we will revive our plan to march.”

As plans were made for the March on Washington in 1963, a young John Lewis, Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was invited to speak. He prepared a fiery text criticizing the Kennedy administration for delay on civil rights. Older activists told him that if he delivered it, he would not only anger Kennedy, who was trying to get the Civil Rights Act through Congress; he would dishonor Randolph, whose earlier work had made the 1963 march possible. Lewis revised his remarks. That’s another lesson learned during the long civil rights movement: how to pressure without alienating one’s allies.

In addition to 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back, David Krugler is the author of two other works of nonfiction: The Voice of America and the Domestic Propaganda Battles, 1945-1953 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2000) and This Is Only a Test: How Washington, D.C., Prepared for Nuclear War (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006). A novelist as well, Krugler has written two World War II spy thrillers, The Dead Don’t Bleed (2016) and Rip the Angels from Heaven (2018), both published by Pegasus Crime.