Christopher Columbus’s Fourth Voyage

“In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.”

It’s a simple rhyme, taught to thousands of young children when most history instruction focused on names and dates. This simple lesson ignores the broader story of Christopher Columbus’s four voyages to the New World and the impact those explorations had on Europe and the Americas. Columbus’s last voyage left Europe on May 11, 1502, and continued his quest for a sea route to China, this time by exploring the coastal areas west of the Caribbean islands. Though he failed to achieve his goal, his voyages launched a new age of European exploration, colonization, and a nightmare for the indigenous Caribbean people. His legacy is complicated. “After five centuries, Columbus remains a mysterious and controversial figure who has been variously described as one of the greatest mariners in history, a visionary genius, a mystic, a national hero, a failed administrator, a naïve entrepreneur, and a ruthless and greedy imperialist.”

Given the variety of viewpoints about Columbus, it is no wonder some try to simplify his story.

One benefit of contributing to our We the Teachers blog is the opportunity to research various topics in American history. I always learn things I either did not know or had forgotten. Columbus’s voyages, especially trips two, three, and four, are no exception. For example, I did not know that 11-year-old Christopher Columbus’s first sailing experience was on a merchant ship. Nor did I know that when he was 25, by clinging to his ship’s debris and floating to shore in Portugal, he survived a pirate attack that destroyed and sank his vessel. It also surprised me that before Columbus secured financial support for his first expedition from Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castille, he embarked on a comprehensive self-study of mathematics, astronomy, navigation, and cartography, subjects he needed to master to implement his plan.

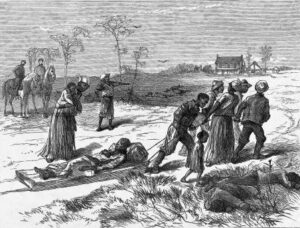

These facts paint a picture of a driven, ambitious man determined to make his mark in a violent and dangerous world. His experiences may have contributed to his assessment of the people he encountered in the New World as people to exploit for his purposes. “They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance …,” he recorded in his diary. “They would make fine servants… With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.” Though he was denied permission to enslave natives on at least one occasion, Columbus and his men ignored the restriction, enslaving hundreds throughout his career.

Columbus was not the first to seek a sea route from Europe to Asia. The challenge had engaged European thinkers since the days of early Rome. Traveling overland was long, arduous, and dangerous. If a sea route could be discovered, it promised to make trade with Asian nations more profitable and gain access to goods not found or produced in Europe.

Columbus’s insight was to reach the East by sailing west. His mistake was mathematical. He assumed the globe was smaller than it is, so his estimate of how long the trip would take was unrealistic. He also did not know that the Western Hemisphere blocked his path.

Impressed by the gold, spices, and human captives Columbus brought back from his first expedition, the Spanish crown authorized a quick turnaround for his next voyage with a significantly larger fleet of seventeen ships and 1200 men. Also on the expedition were settlers encouraged by promises of large quantities of gold in the islands. The Spanish crown ordered Columbus to Christianize all the natives he encountered.

Upon his return to Hispaniola, the settlement he founded on his first landing, Columbus discovered it decimated by disease and war with the natives. The new settlers he brought quickly grew discouraged by the exaggerated claims of gold on the island. Columbus decided to return to Spain for supplies, leaving his brother Bartholomew in charge of Hispaniola. His third trip was equally disastrous. The Spaniards on Hispaniola accused Christopher and his brother of maladministration. A new Spanish administrator arrived in September 1499, investigated the allegations, arrested Columbus, and sent him home in chains.

He attempted to salvage his reputation on his fourth voyage by finally locating the sea route to Asia. Ironically, he landed on the coast of Nicaragua and Panama, the area future visionaries saw as the best place to construct a man-made canal from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. The Panama Canal is now the route Columbus hoped nature had provided.

Columbus’s expeditions decimated the native Taino population of the Caribbean. It began an age of exploration that led to the triangular trade of the colonial era, where raw goods produced with enslaved labor were shipped to Europe, where rum and other manufactured goods were produced and traded in Africa for more enslaved African people. Thus, his expeditions are important because they permanently changed the relationship between Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

How should we teach students about Columbus?

Though I am no longer in the classroom, every time I research a topic for a blog post, I evaluate how I would change my lessons. In the past, when teaching Columbus, I assigned my students an excerpt from historian David E. Stannard’s book, American Holocaust. Stannard’s descriptions of Columbus’s treatment of the indigenous people are horrific. His descriptions of contemporaneous Europe are equally horrible. The students debated whether men from a violent place would treat strangers non-violently.

Here is one way to change that lesson. First, I would divide the students into groups to analyze each of Columbus’s four voyages and ask them to consider the stated goals of each trip, plus what he learned from each expedition. Next, I would assign Documents and Debates: Early Contact from Volume 1 of TAH’s Core Document Collection so that students read and discuss how the treatment of Native Americans was debated in Columbus’s time before exposing them to a historian’s interpretation. Students should learn that the debate over Columbus’s actions and, thus, his legacy began in the 1490s and continues today. They are free to read the primary and secondary sources and reach their conclusions about the man and his times.

Ray Tyler was the 2014 James Madison Fellow for South Carolina and a 2016 graduate of Ashland University’s Masters Program in American History and Government. Ray is a former Teacher Program Manager for TAH and a frequent contributor to our blog.