The Founders, the Presidency & Stephen F. Knott

In his new study of the presidency, Stephen F. Knott, Thomas and Mabel Guy Professor in Teaching American History’s Master of Arts in American History and Government program, traces what he views as a long devolution of the executive office, culminating in the surprising election result in 2016. The Lost Soul of the American Presidency: The Decline into Demagoguery and the Prospects for Renewal will appear from the University Press of Kansas on October 25. Knott, who teaches National Security Affairs at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, has written five other books on the presidency, including two studies of Ronald Reagan and a book he co-authored with Tony Williams, Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance That Forged America (Sourcebooks, 2015). We asked Professor Knott to explain why he believes the presidency no longer functions as the framers of the Constitution intended.

Since the American founding, how has the presidency changed?

I argue that the president’s role has been unmoored from what the founders envisioned 232 years ago. The founders saw the president as a head of state who stood above the partisan fray, representing the nation as a whole. Today, the president represents the will of an impassioned majority. The president has become a cheerleader for popular feelings, putting at risk those who don’t share them.

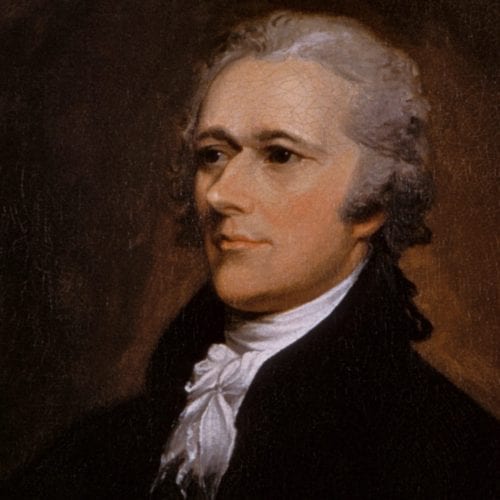

As a Hamilton scholar, you know he argued in Federalist 68 that the Electoral College, which delegated presidential selection to electors chosen by state legislators, guaranteed

. . . that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States.

What happened?

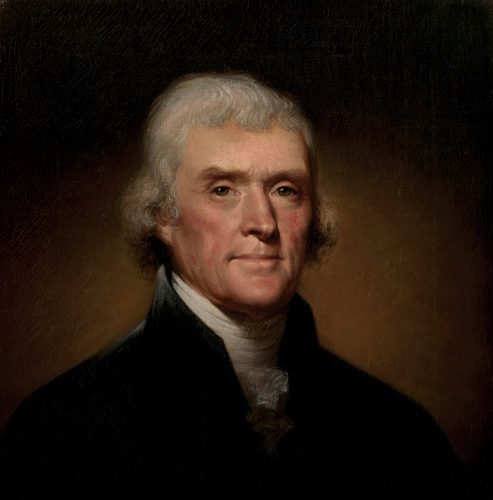

Thomas Jefferson decided that the “revolution of 1800” must revamp the presidential selection process and re-found the office on a new understanding.

He launched the presidency on a populist course that, in the long run, undermined the intentions of the framers of the Constitution. The founders I consider critical—Washington, Hamilton, and Madison—worried that demagoguery could destroy the republic. Hamilton feared demagogic leaders would tap passions to sway public sentiments. Hence he held the energetic executive responsible for checking popular excess. Jefferson argued to the contrary that public opinion served as the “best criterion of what is best,” and that enlisting and engaging that opinion would “give strength to the government.” As the nation’s only nationally elected figure, the president drew support for an energetic executive directly from the people. Jefferson turned Hamilton’s argument on its head, arguing that popular opinion conferred constitutional legitimacy. Jefferson made this abundantly clear in a letter he wrote to James Madison in 1787: “after all, it is my principle that the will of the Majority should always prevail.”

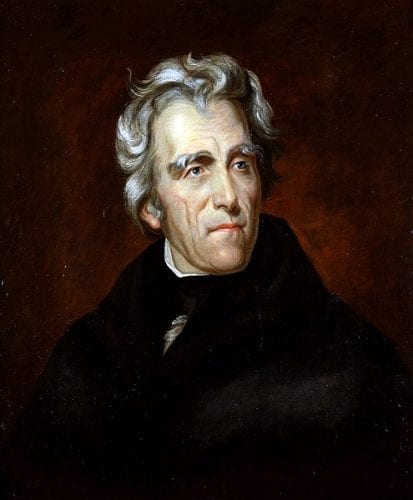

This led to the much more partisan candidacy of Andrew Jackson, who accused his opponents of representing an elite and un-American oligarchy. Jackson believed that “the majority is to govern” and that the president was uniquely situated to speak for that majority. To Jackson, checks on majority rule, including the Electoral College, undermined the principle that “as few impediments as possible should exist to the free operation of the public will.” As a consequence, the Jacksonians expanded the right to vote among white males but stripped free blacks of their voting rights. Jackson changed the nature of the American political order, an order created to allow for reason and reflection and the possibility of statesmanship. Under Jackson, the tyranny of the majority replaced the rule of law.

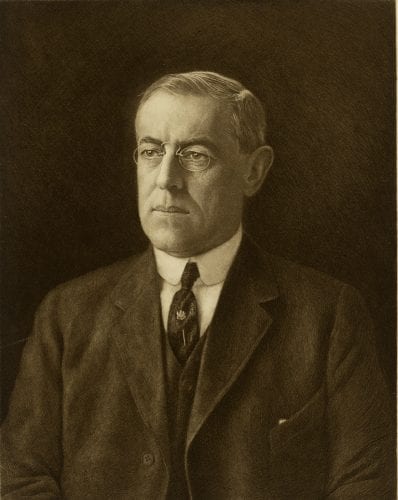

Ironically, Jefferson and Jackson, although opposed to nationalizing or federalizing problems that could be dealt with at the local or state level, paved the way for the progressive presidents of the 20th century. Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt saw the office as a stage on which the president could be as big of a man as he wanted to be. Although each saw himself as the voice of the people, their leadership imposed costs on racial and political minorities.

You say partisanship detached the presidency from its Constitutional role. Yet many observers say that the 2016 election shows the weakness of our party system. Parties can no longer keep the nomination process under their control.

I couldn’t agree more. The presidency has become personalized. Woodrow Wilson considered cigar-chomping party leaders in smoke-filled rooms an impediment to effective governance and did what he could to mitigate their power. Today, the parties no longer screen potential candidates. In 2016, a man who was not a member of the Democratic Party, Bernie Sanders, nearly won the Democratic nomination, while a man who had been a lifelong Democrat, Donald Trump, won the Republican nomination and the presidency. Any personality who can move the majority now sees himself entitled to govern as he sees fit.

So now, instead of speaking for a party, the president speaks for the instincts of a shifting majority? Have fear and reaction—seen in prejudice, identity politics, xenophobia, and isolationism—displaced party goals?

I think so. I’m told the word “passions” appears 66 times in The Federalist. The process of selecting the president was supposed to check those passions, promoting candidates who appealed to reason. But today we prefer candidates who excite the crowds. That reverses the key founders’ vision.

When the parties filtered the nominees for president, the party bosses picked those they thought they could control. Still, they did a fairly decent job of choosing those who would not do harm. For example, they replaced Henry Wallace with Harry Truman. But by then, Progressive presidents had already moved us toward a direct democracy system. Wilson even proposed a national primary for the two parties.

The reforms George McGovern pushed through the Democratic Party in 1972 followed Wilson’s vision, making the possibility of insurgent candidacies more likely. The Republicans moved much more slowly in that direction, yet ironically ended up backing Trump, in my view the most egregious example of this democratized, populist presidential selection process.

Do the greatest presidents show the least ego?

The best presidents have conducted themselves with moderation and magnanimity, although this may mean voters and historians don’t judge them fairly. William Howard Taft did not project a “vision” that would lead the majority into the promised land, even though he supported progressive legislation. He was overwhelmingly defeated for reelection in 1912 in part because he didn’t practice the “little arts of popularity.”

Certainly Abraham Lincoln had a vision for a new birth of freedom. But he had a prudential sense that people have to be brought along. He didn’t see it as his job to fire up the base and attack the opposition. If there was any president who had a reason to go after the opposition, whether the Confederate states or some of their Democratic party allies in the north—it was Lincoln, but Lincoln’s language was very restrained.

Along with exaggerated attacks on opponents come exaggerated promises. Securing the Democratic Party nomination, Obama declared that this would be “the moment when the rise of the oceans beg[ins] to slow.” John F. Kennedy proclaimed at his inauguration that the US would “pay any price, bear any burden” to promote democracy abroad. Trump promises he’ll build a wall and the Mexicans will pay for it. Inflated rhetoric leads to inflated expectations of what the office can deliver. Deep disappointment follows, when it turns out that we can’t remake the world, remake human nature, or even necessarily avert climate change.

How have modern communications contributed to this?

Wilson was the first to use radio, which Franklin D. Roosevelt played to the max. His presidential library in Hyde Park holds letters American citizens wrote him, saying, in effect, “I listened to your fireside chat, and I felt that you were in the room with me. You made me feel loved and cared for.”

John F. Kennedy, during the two years, ten months and two days of his presidency, demonstrated the power of television. His personable performance in the TV debates with Nixon played a role in his election. Even in death, TV elevated him in the national memory. The networks covered his assassination and funeral around the clock, repeatedly showing the image of his young widow and small children. In the aftermath, two thirds of the public claimed to have voted for Kennedy, even though he actually did not get quite 50%.

Obama was the first to use social media, and President Trump relies on it. At last check, he has tweeted over 44,000 times.

Some blame Congress for ceding power to the president in recent years.

That began when Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt assumed responsibility for setting the legislative agenda. Wilson restored the in-person State of the Union speech and in it laid out a laundry list of presidential initiatives.

Yet presidents who have acted as head of state, rather than as party leader or policy developer, have done quite well. They are seen as unifying national figures. In modern times, perhaps Dwight Eisenhower comes closest to that model. Eisenhower never personalized his disputes with the Democratic Party opposition. He had a good relationship with Lyndon Johnson. He disdained Joe McCarthy in part because of his personal attacks on others. I think Eisenhower’s example has a lot to offer us in the 21st century.

How can we return to that model?

I try to be optimistic. One thing we could do is to restore the filtering function that the party leaders used to play. I would favor more super delegates for both conventions—members of Congress and governors who are not pledged to support those who win state primaries. That might at least prevent non-members from winning party nominations.

Ultimately, the American people must change. We’ve been sold a bill of goods about the president. We hear of “presidential government,” as if the other branches didn’t matter. We call the president the most powerful person in the world. We celebrate the office excessively.

We need more and better civics education, teaching us not only about the proper balance of powers, but reminding us of the limits of politics.

Presidents themselves can act as educators—Wilson wanted to be the national teacher, but he taught some wrong lessons. More recently, Ronald Reagan played a unifying role at the D-Day beaches and after the Challenger disaster. Even George W. Bush struck the right tone in the rubble of the World Trade Center. Those nonpartisan moments when Americans are called on to take pride in the nation and embrace their common citizenship—I’m fully in favor of that. It’s when presidents become partisan lightening rods that the trouble begins.