Junípero Serra, Gaspar de Portolá, and the Spanish Conquest of California

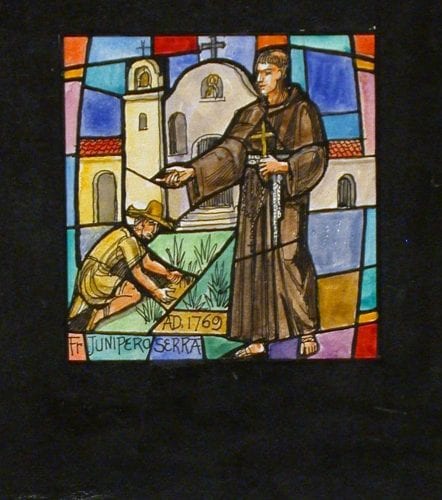

Father Junípero Serra (1713–1784) founded the first Catholic “mission” in what is now present-day California 250 years ago, in July of 1769. To Serra, the enterprise was indeed a mission to convert the natives of America’s Pacific coast. To the secular leader of the expedition, Gaspar de Portolá (1723–1784), the task was to assert Spanish control of this coast, securing it against the claims of Russia.

The Spanish had already established small communities in Baja or lower California, led by the Jesuit order. Now the Spanish crown hoped to gain a foothold further north, in “Alta California,” in the harbors reported to exist along the coast. Both Serra and Portola were responsible to José de Gálvez, the Spanish “Visitor General” who was leading the reorganization of New Spain after the 1763 Treaty of Paris shifted Spain’s New World holdings out of Florida and entirely west of the Mississippi. (Spain regained Florida, now divided into East and West Florida, in another treaty negotiated in Paris—one that was part of the Peace of Paris that ended the American Revolution.)

The Expedition’s Military Leader

Portolá had been sent from Spain to govern Baja California. A reliable army captain, he was chosen to perform difficult tasks: first, to oust the Jesuits from their California missions—since the Jesuit order had been suppressed in Spain—and install the Franciscans in their place. Next, he was expected to secure the northern territory.

In an overland expedition up the coast, Portola looked for two sites reported to offer protected bays for Spanish ships: San Diego and Monterey, sighted from shipboard 150 years before by Sebastien Vizcaino, a Spanish merchant-adventurer. Portola hoped to do his duty while keeping himself and his men alive. Spanish soldiers in America were subject to Indian attack, disease, and starvation (since they understood little about subsisting on the native plants and game). Sea travel was even more perilous than overland ventures. Of three vessels sent up the coast to provision Portola’s 1769 expedition, one sank and another wandered, lost, while those aboard fell ill with scurvy.

The Spiritual Leader’s Mission

Serra, a Franciscan priest and 55-years-old in 1769, zealously pursued an apostolic vision. He was prepared for martyrdom at the hands of the natives, but he meant to convert as many as possible to the Catholic faith. Eighteen years earlier, he’d left a more comfortable life as a professor of theology and philosophy on the island of Mallorca to travel to the New World and evangelize.

Given charge over the missions of Baja California after the expulsion of the Jesuits, Serra had proved himself a forceful and dedicated organizer. He could not, however, make the Spanish agricultural model work on the arid Baja Peninsula, despite efforts to recruit native converts to work the fields. The missions languished as civil and religious authorities jostled for their control, a common pattern in the Spanish conquest of America.

Serra was removed and given other assignments. He acted as an interrogator for the Inquisition, examining settlers accused of witchcraft. He also set out on walking tours as an itinerant evangelist. Covering long distances on an injured, never-healed left leg, he stopped to preach in native communities, even though he didn’t know the native languages. Instead, he demonstrated his consciousness of sin and of the need for God’s redemption by practicing public self-flagellation. Mid-oration, he lashed himself or pounded his chest with a large rock.

When in 1769 he was asked to serve as “father president” of the Alta California mission field, he felt he was finally fulfilling his calling. He offered to travel north himself as the first of the missionaries. Like a latter-day, peregrinating St. Paul (sometimes he used the term “gentiles” in reference to the Native Americans), he contemplated founding a “ladder” of missions up the Alta California coast. For now, he joined Portolá’s overland expedition.

Locating Monterey, the Intended Capital

Portolá’s party reached San Diego on June 29, 1769. Portolá stayed only two weeks before setting out again to find Monterey. Left behind with two priests and a detachment of nine soldiers, Serra constructed a rustic chapel, furnished it with devotional objects, and dedicated the San Diego Mission on July 16. Meanwhile, Portolá’s party passed Monterey without finding it. Returning dispirited to San Diego, he assessed the mission’s dwindling provisions and returned to Baja for supplies. Serra stayed in San Diego, insisting he could not abandon the new mission, while still hoping to reach Monterey.

Portolá did find Monterey the next year, establishing a presidio there. Serra, arriving by boat, established the Mission San Carlos on the same day. Although he would found seven other missions along the coast of Alta California, Serra made Mission San Carlos his headquarters. Galvez intended Monterey to serve as the capital of Alta California, and Serra intended to be its spiritual leader. When he found himself at odds with the autocratic military leader at the presidio—after Portolá had returned to Baja to serve as Governor of all California—he simply moved the mission a few miles south to an area he named Carmel.

Refashioning Native Society

Perhaps Serra preferred the Monterey peninsula because the natives of the area, the Rumsen, were a gentle, unwarlike people. While the highly diverse collection of tribes along the Alta California coast had formed no military alliances to resist the Spanish conquest, individual tribes periodically attacked the Franciscan missions. Their interest in the gifts the padres offered them—especially cloth, which they lacked—often gave way to resentment as the padres pressured them to convert to Catholicism and settle at the missions. (Mission San Diego suffered two devastating attacks during Serra’s time.)

Natives who did convert were put to work building structures and farming the land. The Franciscans struggled to keep them working. Around Monterey, the Rumsen practiced a skilled version of hunting and gathering, using pruning and periodic small brush fires to increase fruit yielded by the native plants. To them, European farming practices seemed onerous and unnecessary. Meanwhile, the Spanish friars faced several seasons of crop failures as they learned how to farm in estuarial areas prone to flooding by saltwater. Hence San Carlos, and the other missions in Alta California, initially relied heavily on supplies sent from Mexico. Natives deserted when the food ran low.

They also chafed under Serra’s patriarchal rule. Like many Spanish missionaries in Mexico and the American Southwest who preceded him, Serra expected the natives to participate in daily catechism and used corporal punishment to enforce rules. He sent soldiers to round up native converts who fled the missions, ordering severe floggings when escapees were returned. In reports to the civil authorities, he argued such punishment was essential to the missions’ survival. As one who himself practiced self-mortification, he also thought it beneficial to the natives’ souls. Or perhaps, as at least one biographer (Gregory Orfalea) suggests, he rationalized the floggings in this way. Certainly, he worried that Natives left outside the Missions would be enslaved by later Spanish settlers, without gaining any spiritual benefit.

Serra and Portola in Historical Memory

While Portolá, the dutiful functionary, was largely forgotten, Serra gained renown among later Californians as one of California’s “founders,” recognized perhaps as much for his political as his spiritual leadership. Serra laid a cultural foundation for successive groups of Christian settlers who would follow him. Traveling El Camino Real, the road into California Serra and Portolá blazed, and lovingly restoring the stone and adobe sanctuaries Serra built or inspired, later Californians celebrated Serra for imagining California as one unified spiritual kingdom. In 1931, his statue would be one of two representing California erected at the US Capitol.

Although Serra had dreamed of Christianizing the pagans of a New World, this was not his achievement. At his death, he was probably unaware of having set in motion the destruction of native communities and the decimation of their population. The European diseases that proved so destructive to native communities were particularly virulent in the close quarters of the missions. By the 1830s, when the newly independent state of Mexico secularized the missions, about three quarters of the 80,000 natives baptized in the California missions lay buried in their cemeteries.

Criticism of Serra’s role in undermining native communities arose in the 1980s and 1990s, just as a movement to canonize Serra was gaining momentum. When Pope Francis made Serra the first Hispanic saint in 2015, he praised Serra as a great evangelizer while apologizing for “grave sins . . . committed against the native peoples of America in the name of God.”

Sources Consulted:

Rose Marie Beebe and Robert Senkiewicz, Junípero Serra: California, Indians, and the Transformation of a Missionary. University of Oklahoma Press, 2015.

Steven W. Hackel, Junípero Serra: California’s Founding Father. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

Gregory Orfalea, “Mission San Buenaventura and the Death of Serra,” Journey to the Sun: Junípero Serra’s Dream and the Founding of California. Simon and Schuster, 2014.

Sylvia Poggioli, “Native Americans Protest Canonization Of Junípero Serra,” National Public Radio, September 16, 2015.