The Mexican-American War: 175 Years Later

175 Years Ago Today: Congress Declares War on Mexico, Invoking Manifest Destiny and Destabilizing the House Divided

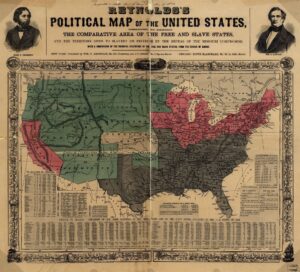

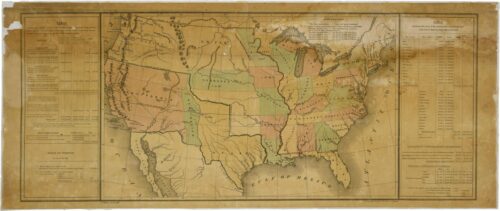

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the young American republic expanded across the continent at a rapid pace. Purchasing the vast Louisiana territory from France, acquiring Florida from Spain, displacing Native sovereignties in the Southeast, annexing the republic of Texas, and eyeing the far reaches of the Pacific, expansionist-minded Americans considered it their “manifest destiny” to “civilize” North America with democracy, Christianity, and capitalism. Ralph Waldo Emerson voiced this nearly unconquerable attitude when he described the United States in 1844 as “a country of beginnings, of projects, of vast designs and expectations. It has no past: all has an onward and prospective look.”

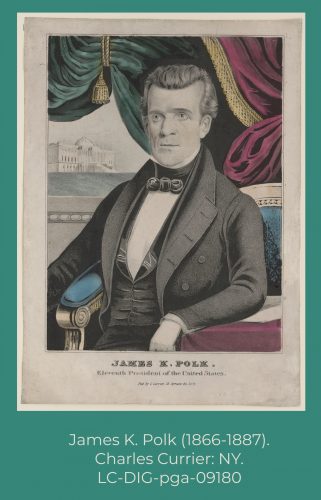

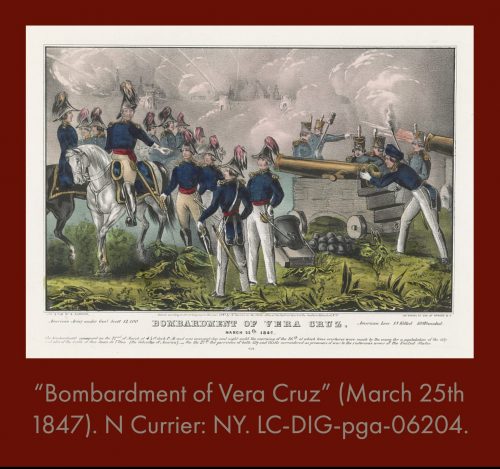

Manifest Destiny, however, also brought great instability to the federal Union. The acquisition of Texas in 1845 sparked a diplomatic crisis between the United States and Mexico. Both nations contested the location of Texas’s southern border. Americans asserted a border along the Rio Grande, while the Mexicans placed the boundary north of that, along the Nueces River. To defend American claims, President James K. Polk deployed the military to the Nueces and ultimately directed General Zachary Taylor to advance south of the river. In response, on April 25, 1846, Mexican troops traversed the Rio Grande, engaged United States forces, and killed several American soldiers in the disputed territory. President James K. Polk demanded that Congress declare war against Mexico to avenge the “shed[ding] of American blood on American soil.” On May 13, 1846, Congress gave Polk what he had always desired: a justification to invade Mexico, secure the Rio Grande as the United States’s southern border, and seize the Mexican province of California. Sensing that Polk intentionally—and immorally—initiated the conflict, an obscure Whig congressman from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln garnered attention when he challenged the president’s presumption that American blood had indeed been spilled on American, and not Mexican, soil. Steadfast in his criticism of “Polk’s War,” Lincoln lost his reelection bid in 1848, concluding his only term in Congress.

The newspaper editor and poet Walt Whitman captured the war fever that gripped an American public eager to “chasten” Mexico. “Let our arms now be carried with a spirit which shall teach the world that, while we are not forward for a quarrel, America knows how to crush, as well as how to expand!” Nearly 90,000 United States soldiers served during the war, two-thirds of whom were amateur citizen-soldiers. The New York Herald depicted Americans’ romantic view of volunteer military service in the republican tradition: “One of the highest tests of a good citizen, is the readiness or reluctance with which he yields his personal liberty . . . when at his country’s call, he leaves his private pursuit and enters the field to fulfill the highest obligation a citizen owes his country.”

A chauvinistic racism underwrote Americans’ confidence in their Manifest Destiny. One ardent supporter of the war called Mexicans “reptiles in the path of progressive democracy” who could never advance beyond their allegedly primitive Indian and Spanish heritages. Only the strong arm of American military power, so went the argument, could wean Mexico away from what was seen as Catholic religious idolatry and veneration of dictators, replacing these with a stable republicanism. Mississippi volunteer William P. Rogers believed that the United States carried a heavy burden to “greatly improve the condition of the poor Mexico.” For Rogers, the war was a paternalistic crusade “promotive of humanity and the cause of freedom and religion

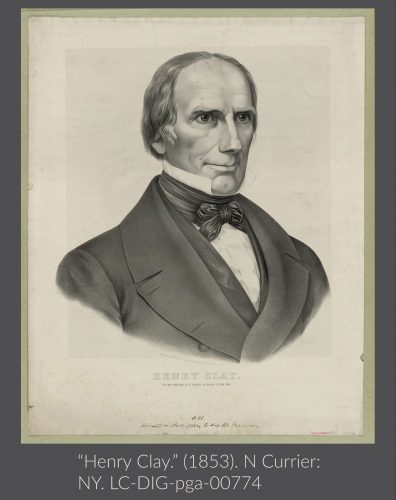

The war nevertheless garnered significant opposition. As a Democrat, President Polk embodied the bellicose assumptions of Manifest Destiny. He sneered at other national sovereignties, considering the United States fully entitled to swift territorial acquisitions across North America. The Whig Party lambasted Polk for instigating what it deemed an unprovoked and reckless war against Mexico. Georgia congressman Alexander H. Stephens condemned the war as “downward progress. It is a progress of party—of excitement—of lust for power—a spirit of war—aggression—violence and licentiousness. It is a progress which, if indulged in, would soon sweep over all law, all order, and the Constitution itself.” Statesman Henry Clay likewise denounced Polk’s militarism as a dangerous harbinger of national destabilization: “War unhinges society, disturbs its peaceful and regular industry, and scatters poisonous seeds of disease and immorality.”

Like many Whigs, Clay assumed that Polk purposely instigated the war to conquer land through which slavery might expand. Though a slaveholder himself, Clay considered the aggressive expansion of slavery a danger to national equilibrium, destabilizing sectional balance, radicalizing political extremes, and, he believed, planting the seeds of race war. Abolitionists expressed an even more earnest opposition to what Frederick Douglass called Polk’s “slaveholding crusade.” Douglass excoriated the Democrats for parading as “the accustomed panderers to slaveholders: nothing is either too mean, too dirty, or infamous for them, when commanded by the merciless man stealers of our country.”

Nervous that “Polk’s War” would yield abundant territorial bounties for slaveholders, Democratic Congressman David Wilmot of Pennsylvania proposed in 1846 that, “as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any territory from the Republic of Mexico by the United States, by virtue of any treaty which may be negotiated between them . . . neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory.” Wilmot aimed to keep western lands free for white antislavery settlement but also free from African American residents.

Although Wilmot’s Proviso failed to pass Congress, its implications held great resonance for the future. When Mexico surrendered in 1848, the United States acquired as a prize of war the vast Mexican Cession, stretching from current-day New Mexico to California. The great twentieth-century American historian David M. Potter called this moment “an ominous fulfillment” of Manifest Destiny. Ralph Waldo Emerson predicted the trouble that would follow. He anticipated that the United States would “conquer Mexico, but it will be as the man who swallows the arsenic which will bring him down in turn. Mexico will poison us.” By 1848, the triumph of national expansion had established the conditions of an irrepressible conflict over the question of slavery’s expansion into the western territories.

As Potter wrote in his magisterial account of the 1850s, “the slavery question became the sectional question, the sectional question became the slavery question, and both became the territorial question.” By 1848, the antislavery movement crystallized into an organized political coalition that insisted that slavery could never spread beyond its current place in the American South. Antislavery adherents maintained that the territories must be preserved for free labor, uncorrupted by the exclusionary oligarchic and aristocratic influence of slaveholders. The incompatible social architectures of the North and South had made the Union a “house divided” against itself.