The Peculiar Institution vs. The Word Fitly Spoken

Early one school year, I asked my Advanced Placement U.S. History students what questions they hoped to have answered in the course. One thoughtful student said she wanted to understand how people justified slavery before the Civil War. She had put her finger on one of the most troubling parts of American history. She had also stumbled upon a consistent challenge in the study of history: presentism. That is, the tendency to judge the actions of previous generations by modern ideals and values. Presentism is especially difficult to avoid when studying the brutal, dehumanizing chattel labor system of antebellum America. Teachers must not risk excusing slavery. Some evils are, in fact, evil.

I recalled the challenge of teaching students how slave owners justified owning other human beings as I read the documents in Teaching American History’s Documents and Debates, Chapter 12: The Peculiar Institution: Positive Good or Pernicious Sin? When I first saw the title, I thought, Of course it is a pernicious sin! How could it be anything but a pernicious sin? Yet, as a student and teacher of American history, I knew that Americans in the antebellum era hotly debated the question.

For me, this was one of the best reasons to use primary sources with students. Instead of me explaining the view that slavery was a positive good, I could let John C. Calhoun or George Fitzhugh explain it in their words. Although I was comfortable expressing support for the abolitionist point of view, I wanted the students to hear from the abolitionists themselves, people like William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass and Angelina Grimke. As they studied the era, students frequently speculated about how future generations of students would view current issues through the presentism of their era. “Are there things we find acceptable today that Americans of the future will find sinful?” That question reminded me of how grateful I was to be part of Teaching American History’s community of MAHG students and alumni, where I first learned about “the word fitly spoken.”

In 2012, I attended a multi-day colloquium sponsored by TAH on Abraham Lincoln. The colloquium was led by Peter Schramm, a congenial, Hungarian-American, larger-than-life figure instrumental in the founding of the Ashbrook Center and Teaching American History. Peter assigned Lincoln’s “Fragment on the Constitution and Union” for one session of the colloquium. Although I didn’t know it at the time, this document was destined to become my absolute favorite document to teach.

Lincoln’s “fragments” are notes to himself that have survived to the present day. He wrote the fragment on the Constitution and Union in February of 1861, after his election as president but before his inauguration. Lincoln wrestles with the possibility that his presidential oath will require him to wage war to preserve the Union. He appears to be asking himself what principle would justify the bloodshed required to win such a war. He writes that “without the Constitution and the Union” the nation would not enjoy as much success as it did. Still, Lincoln surmises that the driving force behind the American Revolution and the growth and prosperity the nation enjoyed in 1860 was the principle of “Liberty to all.” Without this principle, our fathers may have fought, but were unlikely to have won a lasting independence. They would have been fighting to secure “a mere change in masters.” With this principle, they founded a nation offering “a path for all … hope to all – and as a consequence, enterprise and industry to all.” Lincoln, quoting Proverbs 25:11 of the Bible, called the expression of this principle “the word fitly spoken” which had proved to be an “apple of gold” to the American people. The Constitution and the Union were the frame protecting the apple of gold – liberty to all.

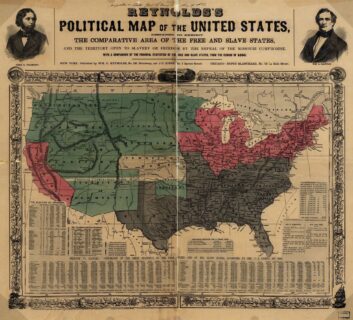

A colleague in the TAH weekend colloquium shared the way she used Lincoln’s Fragment. She created a bulletin board, with a Golden Apple, and framed it with silver borders. Then, when students discussed challenging topics, – Manifest Destiny, for example – she asked them to connect the topic to “the word fitly spoken.” Did the decisions made and policies embraced support the principle of “Liberty for All,” or did it conflict with that principle? Clearly, slavery did not fit with the apple of gold. Yet, as the debate between abolitionists and slave owners raged from the 1830s through the 1850s, slavery enjoyed some measure of protection within the frame of silver – the Constitution and the Union.

When I returned to school after the weekend colloquium I bought a huge bulletin board, recruited a talented art student to create a golden apple and place it on the board. Next, I stapled stenciled letters spelling “Union and Constitution” in a “frame” around the apple. My students read and discussed Lincoln’s fragment early in the course. We then had a framework to revisit first principles – the Declaration of Independence’s expression of liberty and equality for all. We had a living bulletin board to access in those precious teachable moments. So, when students asked how slavery’s proponents justified slavery, I asked them, what do you think? Did they fail to understand the principle of the word fitly spoken? Did they fail to value the apple of gold? Is the apple of gold something each generation of Americans must strive to preserve and defend?

At Teaching American History, we believe students best understand history when they are encouraged to dive into the primary sources, closely reading the words written by the authors of the time – even the words of those whose views we find reprehensible – putting their questions to those authors themselves. In this way, students reach their own conclusions about the choices made by Americans of the past. Almost invariably, students recognize those words of our past that proclaim a timeless truth. Discovering these truths for themselves, they never forget them. We encourage you to engage your students in a close reading of these documents as they discuss the debate over the abolition of slavery and its consequences for today’s pluralistic democracy.

Documents in this chapter include:

A. American Anti-Slavery Society, Declaration of Sentiments, December 6, 1833

B . Angelina Grimké, Appeal to Christian Women of the South, 1836

C. Southern Runaway Slave Notices, 1839 and “Our Peculiar Domestic Institutions,” 1840

D. Frederick Douglass, “I have as much right in this country as any other man,” June 8, 1849

E. George Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, or, The Failure of Free Society, 1854

F. Number of Slaves in the Territory Enumerated, 1790 to 1850, U.S. Census Bureau

We have also provided audio recordings of the chapter’s Introduction, Documents, and Study Questions. These recordings support literacy development for struggling readers and the comprehension of challenging text for all students.

Teaching American History’s We the Teachers blog will feature chapters from our two-volume Documents and Debates with their accompanying audio recordings each month until recordings of all 29 chapters are complete. In today’s post, we feature Volume II, Chapter 12: The Peculiar Institution: Positive Good or Pernicious Sin. On May 25, we will highlight Chapter 26: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 from Volume II of Documents and Debates in American History. We invite you to follow this blog closely, so you will be able to take advantage of this new feature as the recordings become available.