Secession in Arkansas and Tennessee

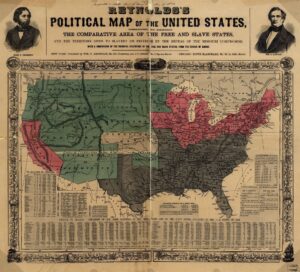

In the upper South, during the secession crisis of early 1861, the circumstances of Missouri, Kentucky, Arkansas, and Tennessee were similar in many respects. Majorities in each were both proslavery and Unionist, but each also had significant radical secessionist minorities determined to lead their states into the Southern Confederacy. Each of these states also had Democratic executives who favored secession. Moreover, while these states had strong economic ties to both the North and South, culturally they were southern through and through, having been settled primarily by migrants from slave states. Missouri and Kentucky, however, never seceded from the Union. Arkansas and Tennessee did, begging the question: why? Part of the answer resides in the intensity of the unionist and secessionist feeling in each state. Both Missouri and Kentucky had very able and resolute unionist leaders, who were supported by many in their states, and to whom secession was anathema. In Tennessee and Arkansas, the unionist sentiment seemed to be weaker than in their sister slave states in the upper South and was more readily abandoned once the prospect for compromise was lost and war became imminent.

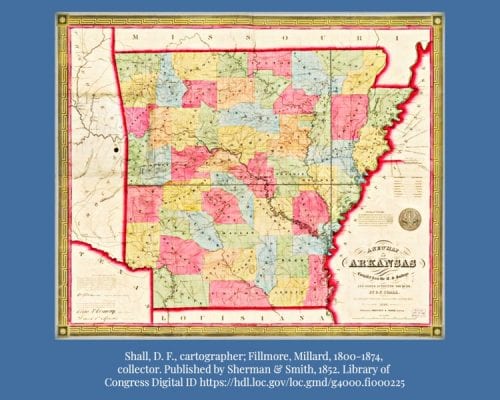

In the decades leading to the Civil War, the majority of Arkansas’ electorate embraced the Compromise of 1850 and opposed radical positions from both the North and South. After Lincoln’s election, despite their deep animosity toward the president-elect and his party, very few Arkansans openly advocated secession. Most thought that South Carolina, the first state to secede, had acted precipitously and without justification. Despite the unpopularity of secession, on January 16, 1861 the state legislature passed a bill to hold a convention to determine whether or not to secede from the Union. In the election of delegates, unionists were elected by a large majority. But because the delegates were allocated not according to population but by county, the majority of unionist delegates in the convention was slim.

Less than a month after this, in Little Rock, where secessionist sentiment was strongest, Governor Henry M. Rector was pressured into sending an ultimatum to Captain James Totten, commander of the Little Rock Arsenal, warning him that if he did not evacuate the arsenal, 5,000 state troops would attack. To avoid bloodshed in a hopeless effort to defend the arsenal, Totten evacuated on February 8.

During this period, elections for delegates to the state convention were held in which candidates ran primarily as supporters of the Union or secession. It is evident from the campaign that in Arkansas there was little support for the most extreme states’ rights positions; but on the other hand, very few candidates ran as unconditional unionists, either. The people of Arkansas rejected the idea that Lincoln’s election justified secession. Nevertheless, unionist candidates, who were often railed against by their opponents as “submissionists” and “abolitionists,” took great pains to distance themselves from the Lincoln administration.

When the convention met in Little Rock on March 4, the day of Lincoln’s inauguration, the delegates elected a unionist to preside over its sessions. The convention quickly rejected any immediate secessionist provision, the unionists arguing that until some overt act was committed by Lincoln and the North no casus belli existed. Another proposal for compromise, which the majority passed, was to send representatives to a convention of states, where amendments to the Constitution of the United States could be drafted to protect slavery and southern rights. Despite the popularity of this measure among moderates in the Upper South, it never gained the necessary support to effect this object and avert war.

The secessionists, recognizing that the convention would not pass a secessionist resolution, proposed that the question be decided by the people through referendum. The unionist delegates rejected this measure, until it was agreed that the matter would not be decided until August, a delay intended to allow for a cooling of secessionist ardor. After the convention’s close, Arkansas probably would have continued to drift along rudderless if events had not intervened to change the attitudes of many opposed to secession. Because of the firing on Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call for troops, popular opinion quickly changed in favor of secession and war. The convention was reconvened on May 6. On that same day, it passed a proposal for Arkansas to leave the Union by a vote of 65-5. The following day the secessionist ordinance was formally signed.

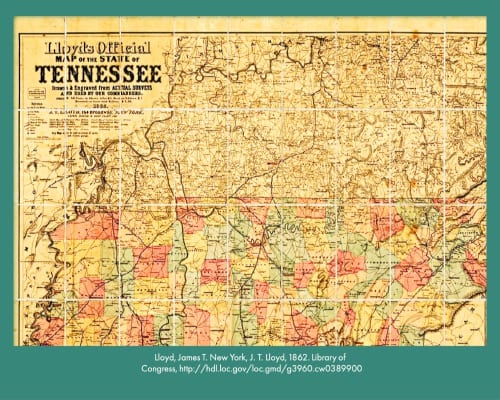

In Tennessee as in Arkansas, during the secession crisis of 1861 the support for immediate secession was weak. Prior to 1861, the people of Tennessee had resisted secessionist movements, believing that the Constitution and Union of the United States were beneficial and should be preserved. In the “volunteer state,” the memory of Andrew Jackson’s staunch opposition to South Carolina’s nullification proclamation in 1832, and his strong statement for Union and against the ideology of state sovereignty, still wielded influence. Many unionists believed that war could be averted and expected the seceding states to return to the Union.

An important supporter of the Union was Senator Andrew Johnson, who disagreed with secessionist arguments about coercion and subjugation, noting that the government had the authority to suppress rebellion. Another supporter of the Union was John Bell, who had been a presidential candidate in 1860 for the Constitutional Union Party. He argued that states that resorted to secession without first exhausting completely all peaceful means for redress could and should be forced to remain in the Union. However, by early 1861 such unequivocal support for the Union was exceptional in Tennessee.

The supporters of secession included Governor Isham G. Harris, who, in a message to the legislature in January 1861, argued that Tennessee should not submit “to the despotism of an unrestrained majority.” To these calls for secession were added the efforts of two commissioners from Mississippi and Alabama, Thomas J. Wharton and Leroy Pope Walker. In their speeches they appealed to the fear that Lincoln would abolish slavery, leading to a “looming specter of racial equality,” a war between whites and blacks, and “racial amalgamation.” The Republicans, Wharton claimed, would soon not only make all races equal, but also give blacks the right to vote. These efforts, he asserted, would “drench the country in blood, and extirpate one or other of the races.” Walker, who became the first Confederate secretary of war, warned that if the South did not secede “all would be lost—first ‘our property,’ and ‘then our liberties,’ and finally the South’s greatest treasure, ‘the sacred purity of our daughters.’”

In the end, it was not these demagogic appeals that tipped the scales in favor of secession. Instead, the firing upon Fort Sumter, and Lincoln’s proclamation calling upon the states for troops, convinced many in both Tennessee and Arkansas to take the first steps toward secession.

Bibliography

Ralph Wooster, “The Arkansas Secession Convention,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, v. 13, no. 2 (Summer 1954): 172-95.

Jack B. Scroggs, “Arkansas in the Secession Crisis,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, v. 12, no. 3 (Autumn 1953): 179-224.

Charles L. Lufkin, “Secession and Coercion in Tennessee, the Spring of 1861” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, v. 50, no. 2 (Summer 1991): 98-109.

Charles B. Dew, Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2001).